AI bots strain Wikimedia as bandwidth surges 50%

Crawlers that evade detection

Making the situation more difficult, many AI-focused crawlers do not play by established rules. Some ignore robots.txt directives. Others spoof browser user agents to disguise themselves as human visitors. Some even rotate through residential IP addresses to avoid blocking, tactics that have become common enough to force individual developers like Xe Iaso to adopt drastic protective measures for their code repositories.

This leaves Wikimedia’s Site Reliability team in a perpetual state of defense. Every hour spent rate-limiting bots or mitigating traffic surges is time not spent supporting Wikimedia’s contributors, users, or technical improvements. And it’s not just content platforms under strain. Developer infrastructure, like Wikimedia’s code review tools and bug trackers, is also frequently hit by scrapers, further diverting attention and resources.

These problems mirror others in the AI scraping ecosystem over time. Curl developer Daniel Stenberg has previously detailed how fake, AI-generated bug reports are wasting human time. On his blog, SourceHut’s Drew DeVault highlight how bots hammer endpoints like git logs, far beyond what human developers would ever need.

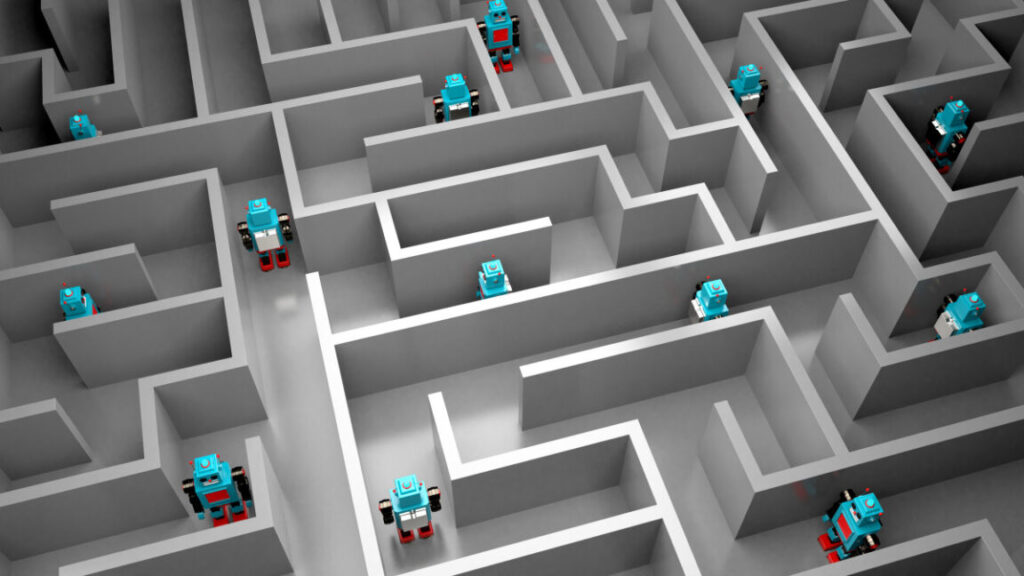

Across the Internet, open platforms are experimenting with technical solutions: proof-of-work challenges, slow-response tarpits (like Nepenthes), collaborative crawler blocklists (like “ai.robots.txt“), and commercial tools like Cloudflare’s AI Labyrinth. These approaches address the technical mismatch between infrastructure designed for human readers and the industrial-scale demands of AI training.

Open commons at risk

Wikimedia acknowledges the importance of providing “knowledge as a service,” and its content is indeed freely licensed. But as the Foundation states plainly, “Our content is free, our infrastructure is not.”

The organization is now focusing on systemic approaches to this issue under a new initiative: WE5: Responsible Use of Infrastructure. It raises critical questions about guiding developers toward less resource-intensive access methods and establishing sustainable boundaries while preserving openness.

The challenge lies in bridging two worlds: open knowledge repositories and commercial AI development. Many companies rely on open knowledge to train commercial models but don’t contribute to the infrastructure making that knowledge accessible. This creates a technical imbalance that threatens the sustainability of community-run platforms.

Better coordination between AI developers and resource providers could potentially resolve these issues through dedicated APIs, shared infrastructure funding, or more efficient access patterns. Without such practical collaboration, the platforms that have enabled AI advancement may struggle to maintain reliable service. Wikimedia’s warning is clear: Freedom of access does not mean freedom from consequences.

AI bots strain Wikimedia as bandwidth surges 50% Read More »