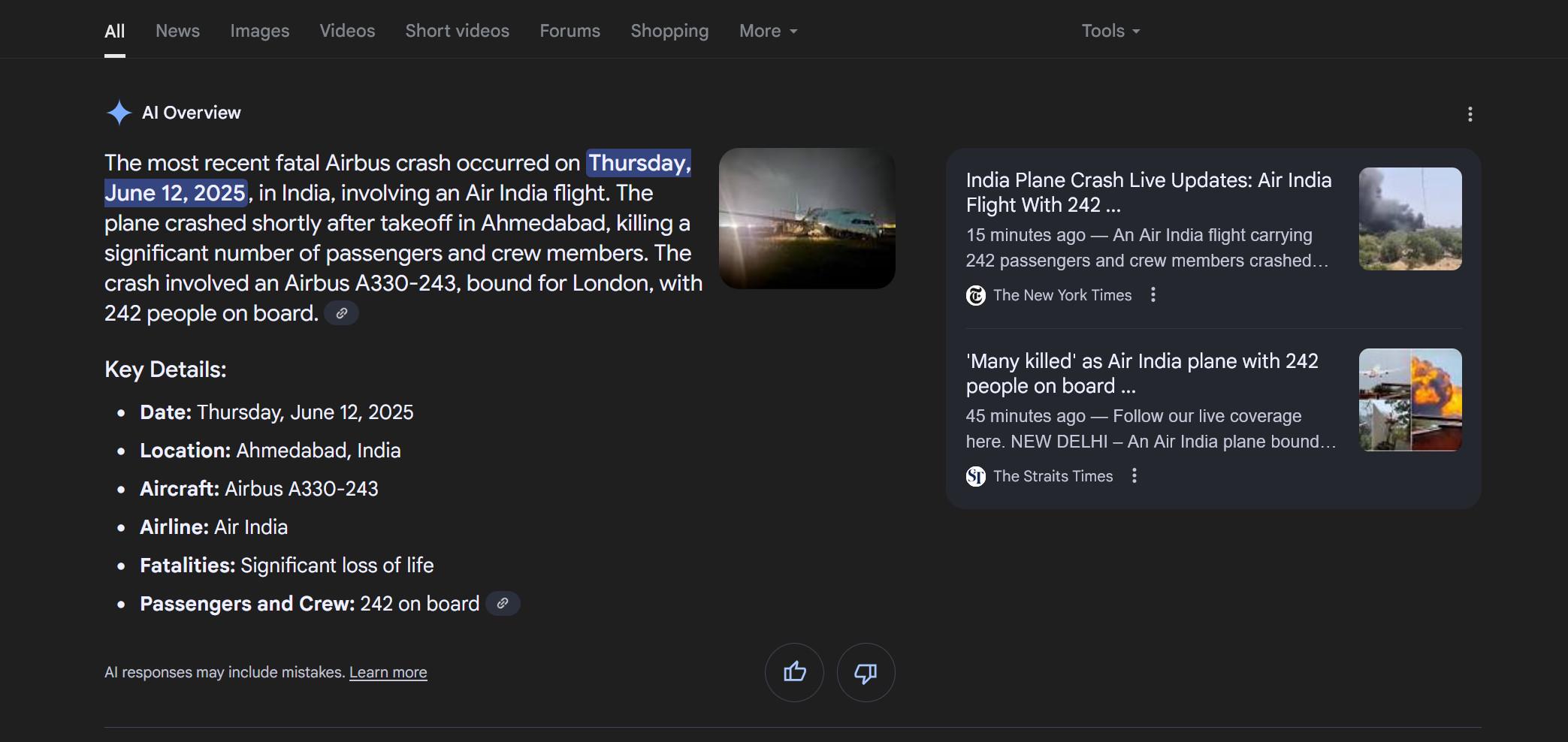

To avoid admitting ignorance, Meta AI says man’s number is a company helpline

Although that statement may provide comfort to those who have kept their WhatsApp numbers off the Internet, it doesn’t resolve the issue of WhatsApp’s AI helper potentially randomly generating a real person’s private number that may be a few digits off from the business contact information WhatsApp users are seeking.

Expert pushes for chatbot design tweaks

AI companies have recently been grappling with the problem of chatbots being programmed to tell users what they want to hear, instead of providing accurate information. Not only are users sick of “overly flattering” chatbot responses—potentially reinforcing users’ poor decisions—but the chatbots could be inducing users to share more private information than they would otherwise.

The latter could make it easier for AI companies to monetize the interactions, gathering private data to target advertising, which could deter AI companies from solving the sycophantic chatbot problem. Developers for Meta rival OpenAI, The Guardian noted, last month shared examples of “systemic deception behavior masked as helpfulness” and chatbots’ tendency to tell little white lies to mask incompetence.

“When pushed hard—under pressure, deadlines, expectations—it will often say whatever it needs to to appear competent,” developers noted.

Mike Stanhope, the managing director of strategic data consultants Carruthers and Jackson, told The Guardian that Meta should be more transparent about the design of its AI so that users can know if the chatbot is designed to rely on deception to reduce user friction.

“If the engineers at Meta are designing ‘white lie’ tendencies into their AI, the public need to be informed, even if the intention of the feature is to minimize harm,” Stanhope said. “If this behavior is novel, uncommon, or not explicitly designed, this raises even more questions around what safeguards are in place and just how predictable we can force an AI’s behavior to be.”

To avoid admitting ignorance, Meta AI says man’s number is a company helpline Read More »