A weird, itchy rash is linked to the keto diet—but no one knows why

Diet downsides

Otherwise, the keto diet is popular among people trying to lose weight, particularly those trying to lose visceral fat, like the man in the case study. Anecdotal reports promote the keto diet as being effective at helping people slim down relatively quickly while also improving stamina and mental clarity. But robust clinical data supporting these claims are lacking, and medical experts have raised concerns about long-term cardiovascular health, among other things.

There are also clear downsides to the diet. Ketones are acidic, and if they build up too much in the blood, they can be toxic, causing ketoacidosis. This is a particular concern for people with type 1 diabetes and for people with chronic alcohol abuse. For everyone else, there’s a list of common side effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, bad breath, headache, fatigue, and dizziness. Ketogenic diets are also linked to high cholesterol and kidney stones.

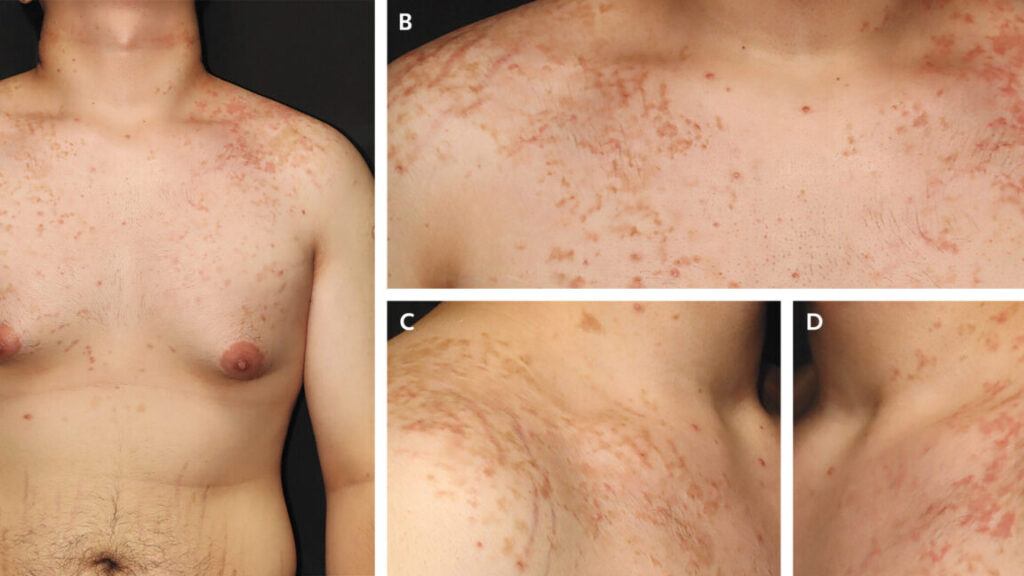

But there’s one side effect that’s well established but little known and still puzzling to doctors: the “keto rash” or prurigo pigmentosa. This rash fits the man’s case perfectly—red, raised, itchy bumps on the neck, chest, and back, with areas of hyperpigmentation also developing.

The rash was first identified in Japan in 1971, where it was mostly seen in women. While it has been consistently linked to metabolic disorders and dietary changes, experts still don’t understand what causes it. It’s seen not only in people on a keto diet but also in people with diabetes and those who have had bariatric surgery or are fasting.

In a review this month, researchers in Saudi Arabia noted that a leading hypothesis is that the high levels of ketones in the blood trigger inflammation around blood vessels driven by a type of white blood cell called neutrophils, and this inflammation is what causes the rash, which develops in different stages.

While the condition remains poorly understood, effective treatments have at least been worked out. The most common treatment is to get the person out of ketosis and give them an antibiotic in the tetracycline class. Antibiotics are designed to treat bacterial infections (which this is not), but they can also dampen inflammation signals and thwart the activity of neutrophils.

In the man’s case, doctors gave him a two-week course of doxycycline and told him to ditch his keto diet. A week later, the rash was gone.

A weird, itchy rash is linked to the keto diet—but no one knows why Read More »