Researchers spot black hole feeding at 40x its theoretical limit

Similar feeding events could explain the rapid growth of supermassive black holes.

How did supermassive black holes end up at the center of every galaxy? A while back, it wasn’t that hard to explain: That’s where the highest concentration of matter is, and the black holes had billions of years to feed on it. But as we’ve looked ever deeper into the Universe’s history, we keep finding supermassive black holes, which shortens the timeline for their formation. Rather than making a leisurely meal of nearby matter, these black holes have gorged themselves in a feeding frenzy.

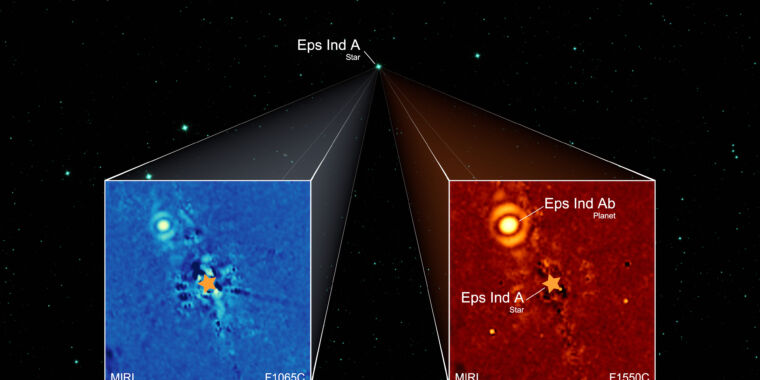

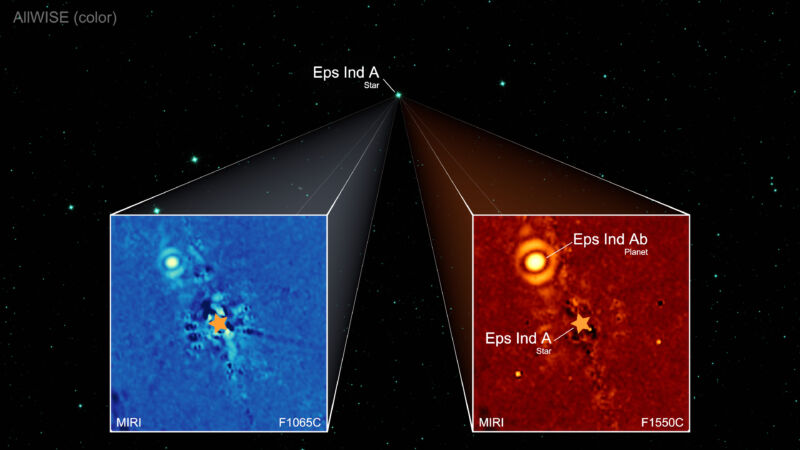

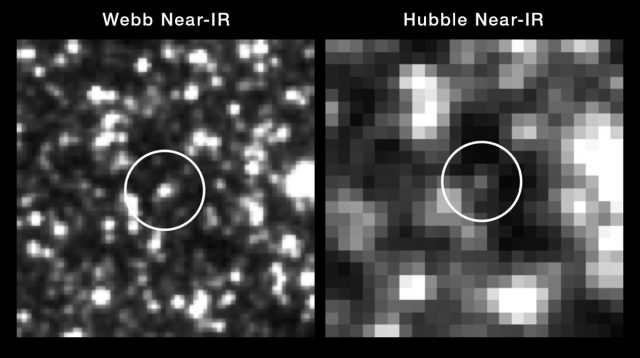

With the advent of the Webb Space Telescope, the problem has pushed up against theoretical limits. The matter falling into a black hole generates radiation, with faster feeding meaning more radiation. And that radiation can drive off nearby matter, choking off the black hole’s food supply. That sets a limit on how fast black holes can grow unless matter is somehow fed directly into them. The Webb was used to identify early supermassive black holes that needed to have been pushing against the limit for their entire existence.

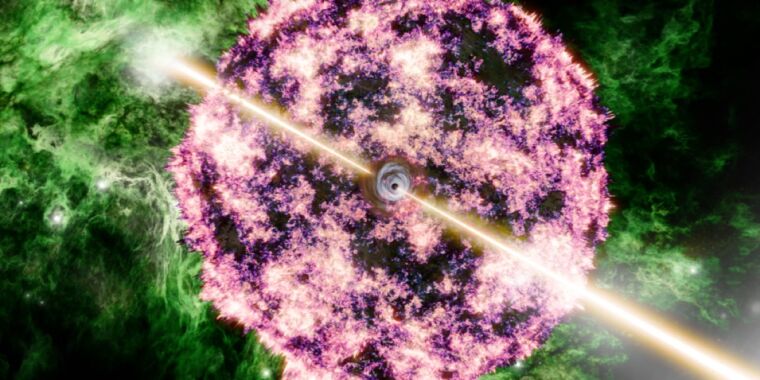

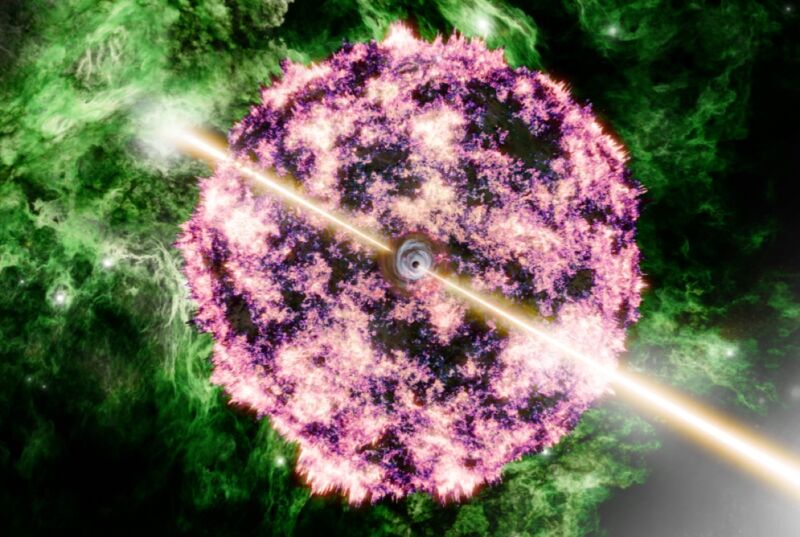

But the Webb may have just identified a solution to the dilemma as well. It has spotted a black hole that appears to have been feeding at 40 times the theoretical limit for millions of years, allowing growth at a pace sufficient to build a supermassive black hole.

Setting limits

Matter falling into a black hole generally gathers into what’s called an accretion disk, orbiting the body and heating up due to collisions with the rest of the disk, all while losing energy in the form of radiation. Eventually, if enough energy is lost, the material falls into the black hole. The more matter there is, the brighter the accretion disk gets, and the more matter that gets driven off before it can fall in. The point where the radiation pressure drives away as much matter as the black hole pulls in is called the Eddington Limit. The bigger the black hole, the higher this limit.

It is possible to exceed the Eddington Limit if matter falls directly into the black hole without spending time in the accretion disk, but it requires a fairly distinct configuration of nearby clouds of gas, something that’s unlikely to persist for more than a few million years.

That creates a problem for supermassive black holes. The only way we know to form a black hole—the death of a massive star in a supernova—tends to produce them with only a few times the mass of the Sun. Even assuming unusually massive stars in the early Universe, along with a few black hole mergers, it’s expected that most of the potential seeds of a supermassive black hole are in the area of 100 times the Sun’s mass. There are theoretical ideas about the direct collapse of gas clouds that avoid the intervening star formation and immediately form a black hole with 10,000 times the mass of the Sun or more, but they remain entirely hypothetical.

In either case, black holes would need to suck down a lot of matter before reaching supermassive proportions. But most of the early supermassive black holes spotted using the Webb are feeding at roughly 20 percent of the Eddington limit, based on their lack of X-ray emissions. This either means that they fed at well beyond the Eddington Limit earlier in their history or that they started their existences as very heavy black holes.

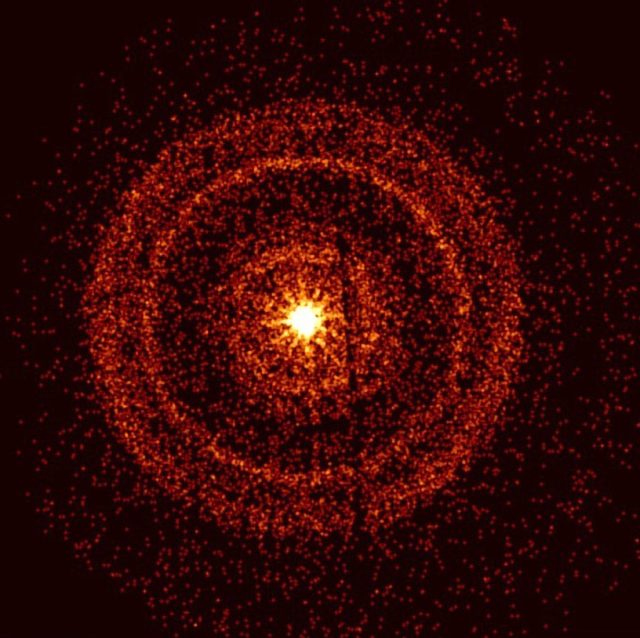

The object that’s the focus of this new report, LID-568, was first spotted using the Chandra X-ray Telescope (an observatory that was recently threatened with shutdown). LID-568 is luminous at X-ray wavelengths, which is why Chandra could spot it, and suggests the possibility that it is feeding at an extremely high rate. Imaging in the infrared shows that it appears to be a point source, so the research team concluded that most of the light we’re seeing comes directly from the accretion disk, rather than from the stars in the galaxy it occupies.

But that made it difficult to determine any details about the black hole’s environment or to figure out how old it was relative to the Big Bang at the time we’re viewing it. So, the researchers pointed the Webb at it to capture details that other observatories couldn’t image.

A fast eater

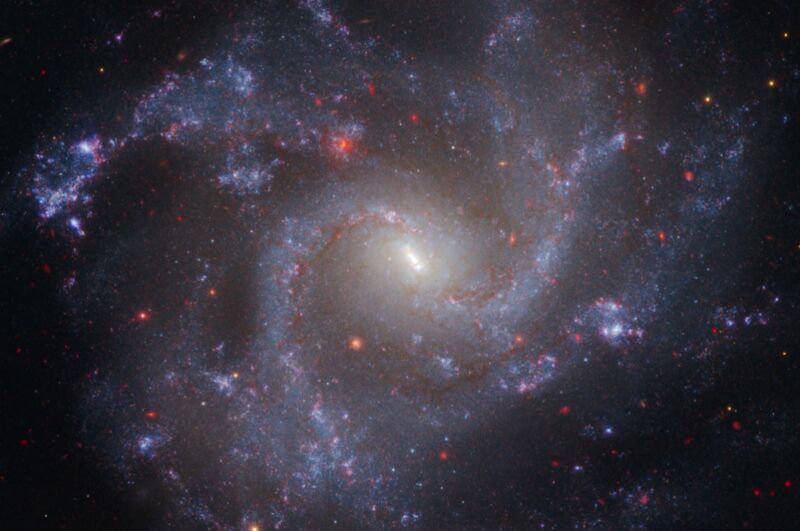

Use of spectroscopy revealed that we were viewing LID-568 as it existed about 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. The emissions from gas and dust in the area were low, which suggests that the black hole resides in a dwarf galaxy. Based on the emission of hydrogen, the researchers estimate that the black hole is roughly a million times the mass of the Sun—nothing you’d want to get close to, but small compared to many supermassive black holes.

It’s actually similar in mass to a number of black holes the Webb was used to identify in galaxies that are considerably older. But it’s much, much brighter (as bright as something 10 times heavier) and includes the X-ray emissions that those lack. In fact, it’s so bright compared to its mass that the researchers estimate that it could only produce that much radiation if it were feeding at well above the Eddington Limit. Ultimately, they estimate that it’s exceeding the Eddington Limit by a factor of over 40.

Critically, the Webb was able to identify two lobes of material that were moving toward us at high velocities, based on the blue shifting of hydrogen emissions lines. These suggest that the material is moving at over 500 kilometers a second and stretched for tens of thousands of light years away from the black hole. (Presumably, these obscured similar blobs of material moving away from us.) Given their length and apparent velocity, and assuming they represent gas driven off by the black hole, the researchers estimated how long it was emitting this intense radiation.

Working back from there, they estimate the black hole’s original mass was about 100 times that of the Sun. “This lifetime suggests that a substantial fraction of the mass growth of LID-568 may have occurred in a single, super-Eddington accretion episode,” they conclude. For that to work, the black hole had to have ended up in a giant molecular cloud and stayed there feeding for over 10 million years.

The researchers suspect that this intense activity interfered with star formation in the galaxy, which is one of the reasons that it is relatively star-poor. That may explain why we see some very massive black holes at the center of relatively small galaxies in the present Universe.

So what does this mean?

In some ways, this is potentially good news for cosmologists. Forming supermassive black holes as quickly as the size/age of those observed by Webb would seemingly require them to have fed at or slightly above the Eddington Limit for most of their history, which was easy to view as unlikely. If the Eddington Limit can be exceeded by a factor of 40 for over 10 million years, however, this seems to be less of an issue.

But, at the same time, the graph showing mass versus luminosity of supermassive black holes the research team generated shows that LID-568 is in a class by itself. If there were a lot of black holes feeding at these rates, it should be easy to identify more. And it’s a safe bet that these researchers are checking other X-ray sources to see if there are additional examples.

Nature Astronomy, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02402-9 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Researchers spot black hole feeding at 40x its theoretical limit Read More »