Developers say AI coding tools work—and that’s precisely what worries them

Ars spoke to several software devs about AI and found enthusiasm tempered by unease.

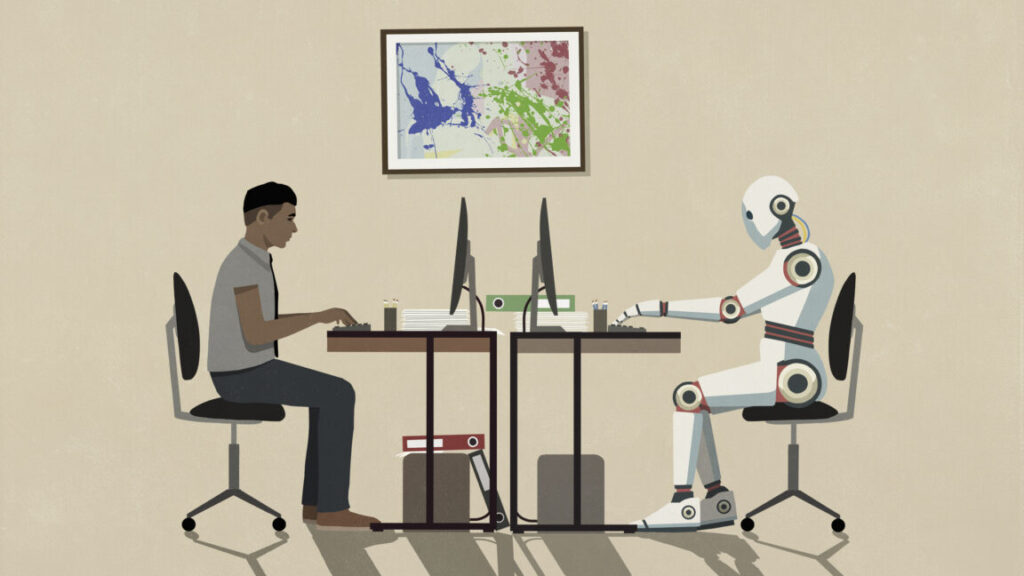

Credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

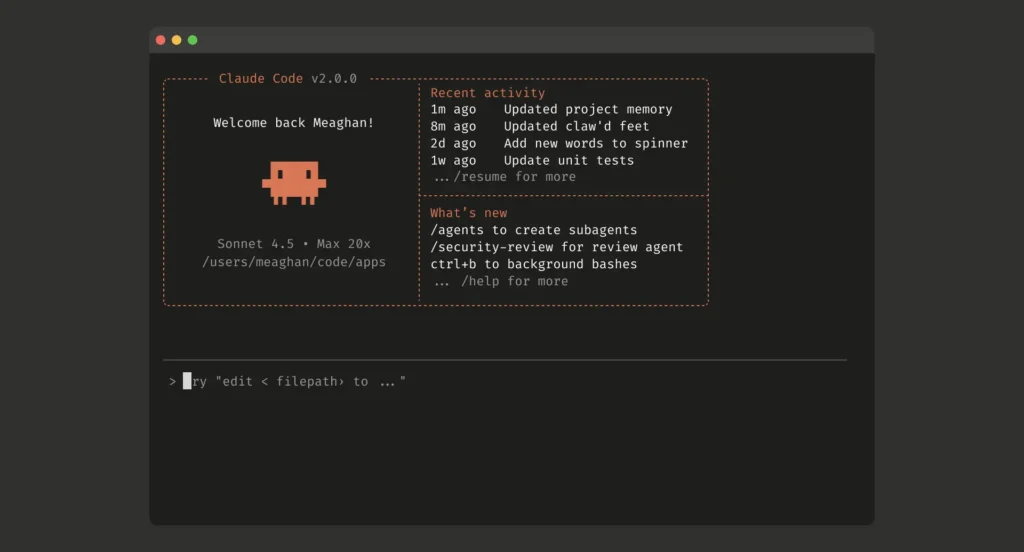

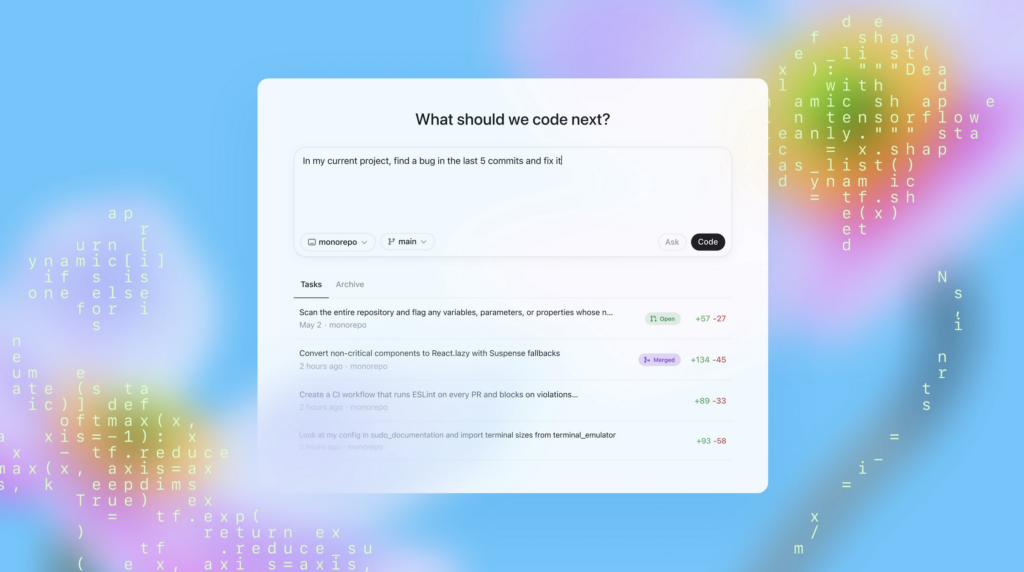

Software developers have spent the past two years watching AI coding tools evolve from advanced autocomplete into something that can, in some cases, build entire applications from a text prompt. Tools like Anthropic’s Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex can now work on software projects for hours at a time, writing code, running tests, and, with human supervision, fixing bugs. OpenAI says it now uses Codex to build Codex itself, and the company recently published technical details about how the tool works under the hood. It has caused many to wonder: Is this just more AI industry hype, or are things actually different this time?

To find out, Ars reached out to several professional developers on Bluesky to ask how they feel about these tools in practice, and the responses revealed a workforce that largely agrees the technology works, but remains divided on whether that’s entirely good news. It’s a small sample size that was self-selected by those who wanted to participate, but their views are still instructive as working professionals in the space.

David Hagerty, a developer who works on point-of-sale systems, told Ars Technica up front that he is skeptical of the marketing. “All of the AI companies are hyping up the capabilities so much,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong—LLMs are revolutionary and will have an immense impact, but don’t expect them to ever write the next great American novel or anything. It’s not how they work.”

Roland Dreier, a software engineer who has contributed extensively to the Linux kernel in the past, told Ars Technica that he acknowledges the presence of hype but has watched the progression of the AI space closely. “It sounds like implausible hype, but state-of-the-art agents are just staggeringly good right now,” he said. Dreier described a “step-change” in the past six months, particularly after Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.5. Where he once used AI for autocomplete and asking the occasional question, he now expects to tell an agent “this test is failing, debug it and fix it for me” and have it work. He estimated a 10x speed improvement for complex tasks like building a Rust backend service with Terraform deployment configuration and a Svelte frontend.

A huge question on developers’ minds right now is whether what you might call “syntax programming,” that is, the act of manually writing code in the syntax of an established programming language (as opposed to conversing with an AI agent in English), will become extinct in the near future due to AI coding agents handling the syntax for them. Dreier believes syntax programming is largely finished for many tasks. “I still need to be able to read and review code,” he said, “but very little of my typing is actual Rust or whatever language I’m working in.”

When asked if developers will ever return to manual syntax coding, Tim Kellogg, a developer who actively posts about AI on social media and builds autonomous agents, was blunt: “It’s over. AI coding tools easily take care of the surface level of detail.” Admittedly, Kellogg represents developers who have fully embraced agentic AI and now spend their days directing AI models rather than typing code. He said he can now “build, then rebuild 3 times in less time than it would have taken to build manually,” and ends up with cleaner architecture as a result.

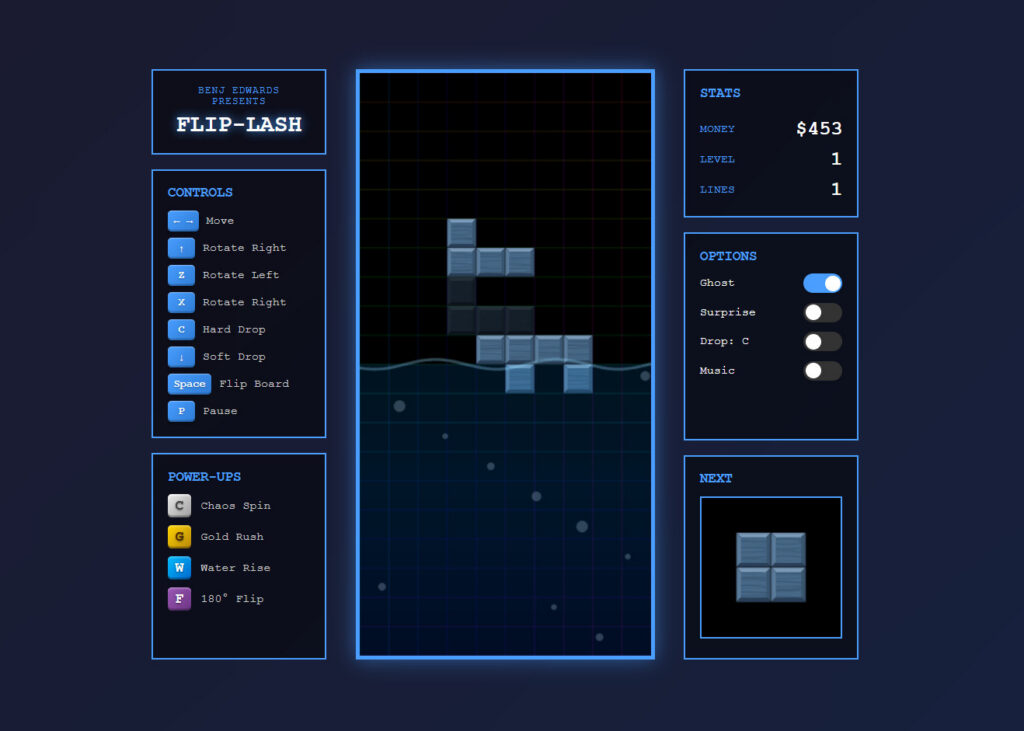

One software architect at a pricing management SaaS company, who asked to remain anonymous due to company communications policies, told Ars that AI tools have transformed his work after 30 years of traditional coding. “I was able to deliver a feature at work in about 2 weeks that probably would have taken us a year if we did it the traditional way,” he said. And for side projects, he said he can now “spin up a prototype in like an hour and figure out if it’s worth taking further or abandoning.”

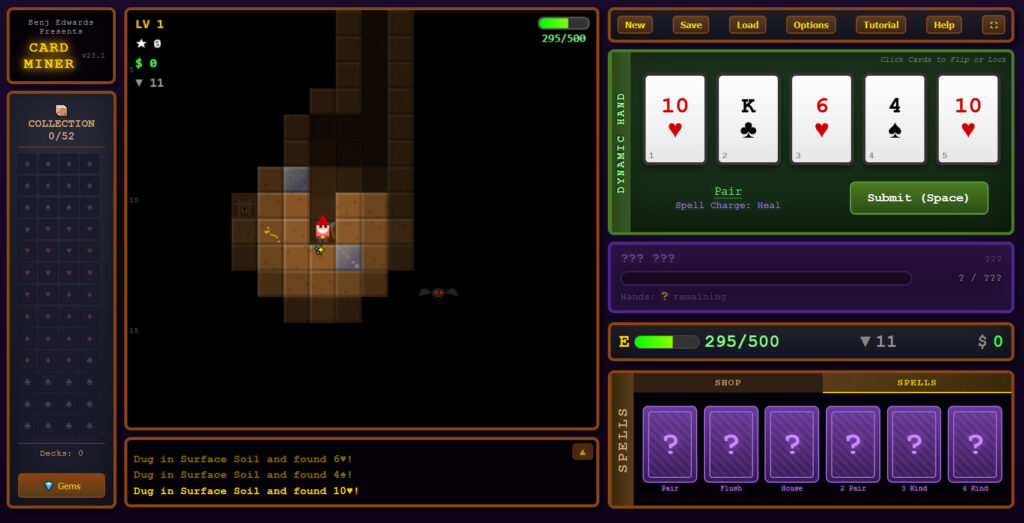

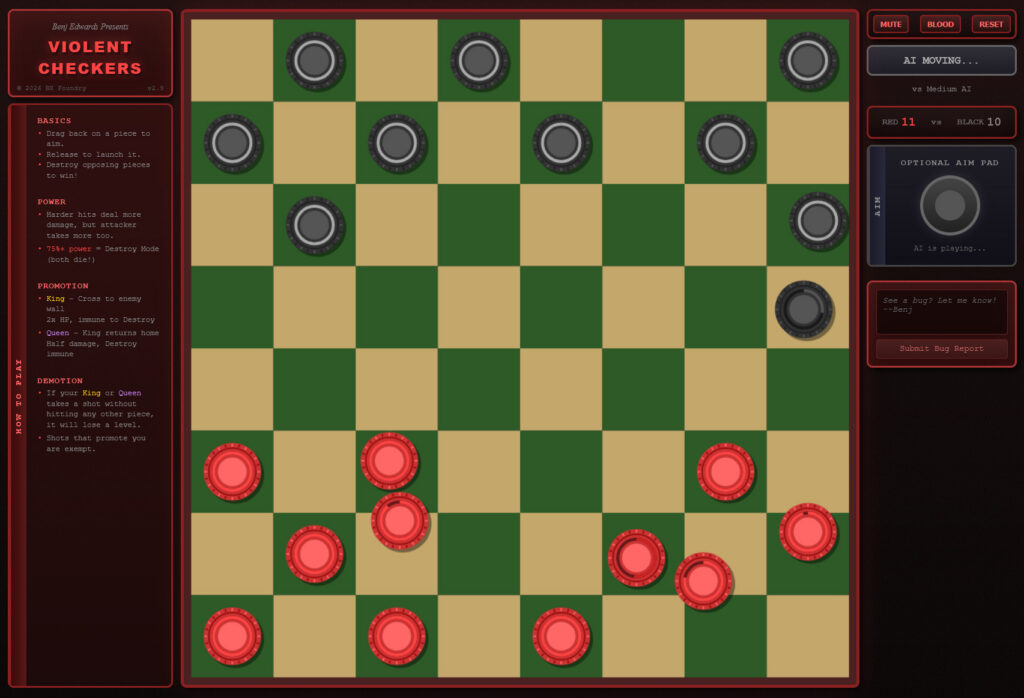

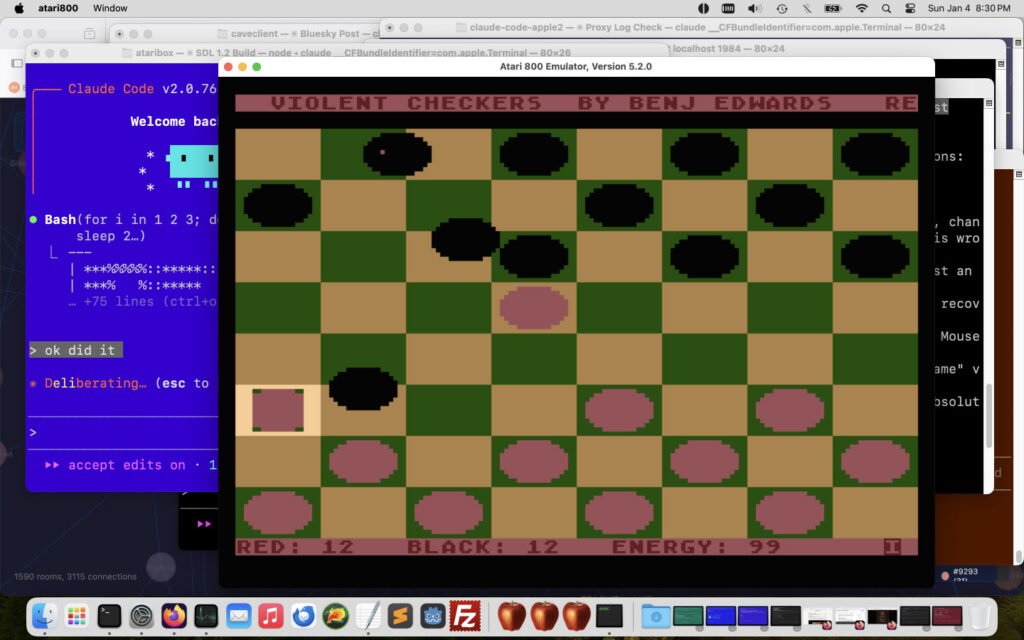

Dreier said the lowered effort has unlocked projects he’d put off for years: “I’ve had ‘rewrite that janky shell script for copying photos off a camera SD card’ on my to-do list for literal years.” Coding agents finally lowered the barrier to entry, so to speak, low enough that he spent a few hours building a full released package with a text UI, written in Rust with unit tests. “Nothing profound there, but I never would have had the energy to type all that code out by hand,” he told Ars.

Of vibe coding and technical debt

Not everyone shares the same enthusiasm as Dreier. Concerns about AI coding agents building up technical debt, that is, making poor design choices early in a development process that snowball into worse problems over time, originated soon after the first debates around “vibe coding” emerged in early 2025. Former OpenAI researcher Andrej Karpathy coined the term to describe programming by conversing with AI without fully understanding the resulting code, which many see as a clear hazard of AI coding agents.

Darren Mart, a senior software development engineer at Microsoft who has worked there since 2006, shared similar concerns with Ars. Mart, who emphasizes he is speaking in a personal capacity and not on behalf of Microsoft, recently used Claude in a terminal to build a Next.js application integrating with Azure Functions. The AI model “successfully built roughly 95% of it according to my spec,” he said. Yet he remains cautious. “I’m only comfortable using them for completing tasks that I already fully understand,” Mart said, “otherwise there’s no way to know if I’m being led down a perilous path and setting myself (and/or my team) up for a mountain of future debt.”

A data scientist working in real estate analytics, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of his work, described keeping AI on a very short leash for similar reasons. He uses GitHub Copilot for line-by-line completions, which he finds useful about 75 percent of the time, but restricts agentic features to narrow use cases: language conversion for legacy code, debugging with explicit read-only instructions, and standardization tasks where he forbids direct edits. “Since I am data-first, I’m extremely risk averse to bad manipulation of the data,” he said, “and the next and current line completions are way too often too wrong for me to let the LLMs have freer rein.”

Speaking of free rein, Nike backend engineer Brian Westby, who uses Cursor daily, told Ars that he sees the tools as “50/50 good/bad.” They cut down time on well-defined problems, he said, but “hallucinations are still too prevalent if I give it too much room to work.”

The legacy code lifeline and the enterprise AI gap

For developers working with older systems, AI tools have become something like a translator and an archaeologist rolled into one. Nate Hashem, a staff engineer at First American Financial, told Ars Technica that he spends his days updating older codebases where “the original developers are gone and documentation is often unclear on why the code was written the way it was.” That’s important because previously “there used to be no bandwidth to improve any of this,” Hashem said. “The business was not going to give you 2-4 weeks to figure out how everything actually works.”

In that high-pressure, relatively low-resource environment, AI has made the job “a lot more pleasant,” in his words, by speeding up the process of identifying where and how obsolete code can be deleted, diagnosing errors, and ultimately modernizing the codebase.

Hashem also offered a theory about why AI adoption looks so different inside large corporations than it does on social media. Executives demand their companies become “AI oriented,” he said, but the logistics of deploying AI tools with proprietary data can take months of legal review. Meanwhile, the AI features that Microsoft and Google bolt onto products like Gmail and Excel, the tools that actually reach most workers, tend to run on more limited AI models. “That modal white-collar employee is being told by management to use AI,” Hashem said, “but is given crappy AI tools because the good tools require a lot of overhead in cost and legal agreements.”

Speaking of management, the question of what these new AI coding tools mean for software development jobs drew a range of responses. Does it threaten anyone’s job? Kellogg, who has embraced agentic coding enthusiastically, was blunt: “Yes, massively so. Today it’s the act of writing code, then it’ll be architecture, then it’ll be tiers of product management. Those who can’t adapt to operate at a higher level won’t keep their jobs.”

Dreier, while feeling secure in his own position, worried about the path for newcomers. “There are going to have to be changes to education and training to get junior developers the experience and judgment they need,” he said, “when it’s just a waste to make them implement small pieces of a system like I came up doing.”

Hagerty put it in economic terms: “It’s going to get harder for junior-level positions to get filled when I can get junior-quality code for less than minimum wage using a model like Sonnet 4.5.”

Mart, the Microsoft engineer, put it more personally. The software development role is “abruptly pivoting from creation/construction to supervision,” he said, “and while some may welcome that pivot, others certainly do not. I’m firmly in the latter category.”

Even with this ongoing uncertainty on a macro level, some people are really enjoying the tools for personal reasons, regardless of larger implications. “I absolutely love using AI coding tools,” the anonymous software architect at a pricing management SaaS company told Ars. “I did traditional coding for my entire adult life (about 30 years) and I have way more fun now than I ever did doing traditional coding.”

Developers say AI coding tools work—and that’s precisely what worries them Read More »