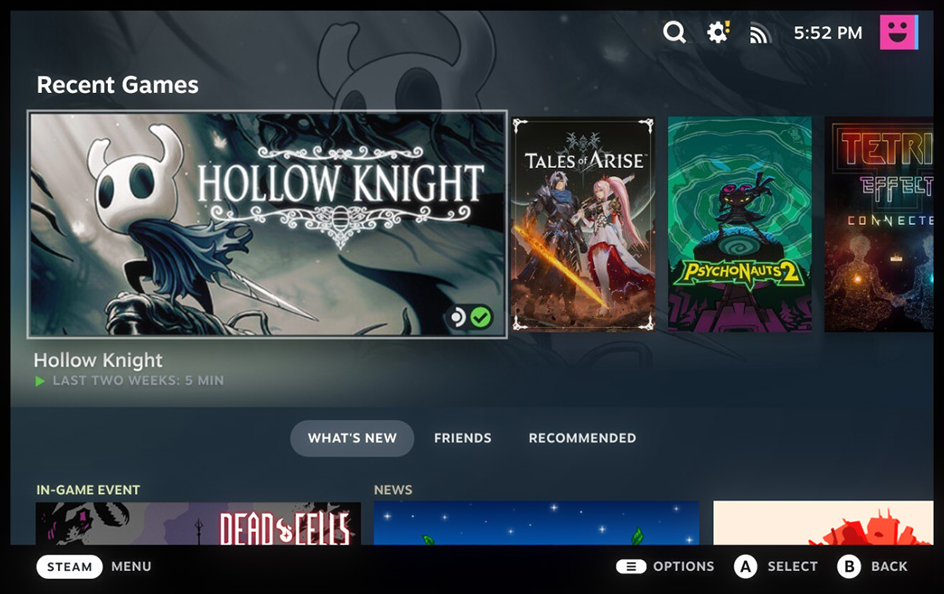

SteamOS continues its slow spread across the PC gaming landscape

Over time, Valve sees that kind of support expanding to other Arm-based devices, too. “This is already fully open source, so you could download it and run SteamOS, now that we will be releasing SteamOS for Arm, you could have gaming on any Arm device,” Valve Engineer Jeremy Selan told PC Gamer in November. “This is the first one. We’re very excited about it.”

Imagine if handhelds like the Retroid Pocket Flip 2 could run SteamOS instead of Android… Credit: Retroid

It’s an especially exciting prospect when you consider the wide range of Arm-based Android gaming handhelds that currently exist across the price and performance spectrum. While emulators like Fex can technically let players access Steam games on those kinds of handhelds, official Arm support for SteamOS could lead to a veritable Cambrian explosion of hardware options with native SteamOS support.

Valve seems aware of this potential, too. “There’s a lot of price points and power consumption points where Arm-based chipsets are doing a better job of serving the market,” Valve’s Pierre-Louis Griffais told The Verge last month. “When you get into lower power, anything lower than Steam Deck, I think you’ll find that there’s an Arm chip that maybe is competitive with x86 offerings in that segment. We’re pretty excited to be able to expand PC gaming to include all those options instead of being arbitrarily restricted to a subset of the market.”

That’s great news for fans of PC-based gaming handhelds, just as the announcement of Valve’s Steam Machine will provide a convenient option for SteamOS access on the living room TV. For desktop PC gamers, though, rigs sporting Nvidia GPUs might remain the final frontier for SteamOS in the foreseeable future. “With Nvidia, the integration of open-source drivers is still quite nascent,” Griffais told Frandroid about a year ago. “There’s still a lot of work to be done on that front… So it’s a bit complicated to say that we’re going to release this version when most people wouldn’t have a good experience.”

SteamOS continues its slow spread across the PC gaming landscape Read More »