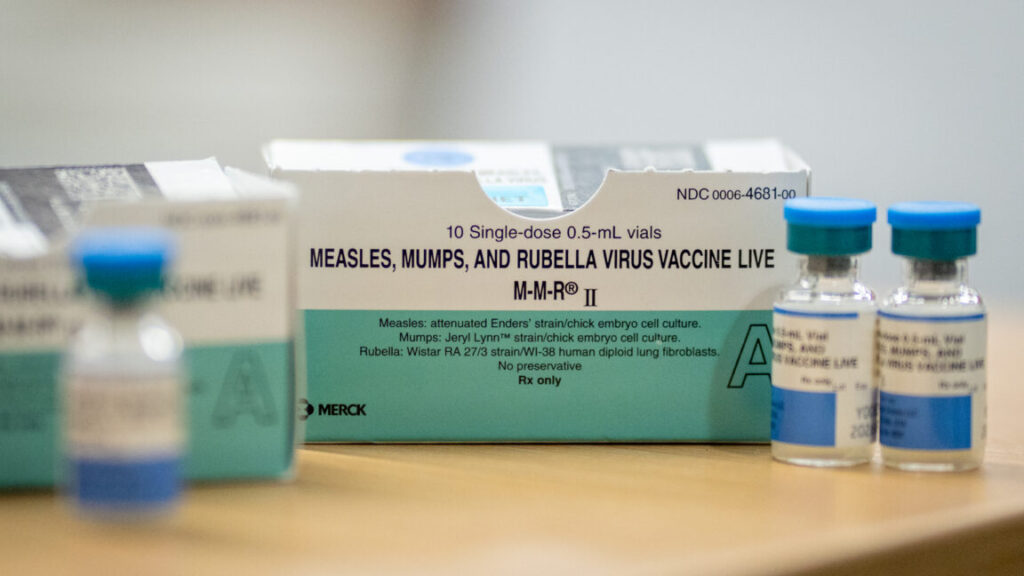

Dozens of CDC vaccination databases have been frozen under RFK Jr.

“Damning”

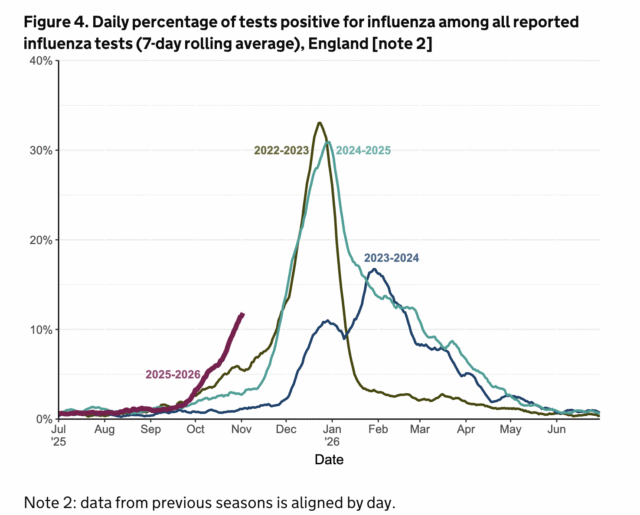

Overall, a lack of updated data can make it more difficult, if not impossible, for federal and state health officials to identify and rapidly respond to emerging outbreaks. It can also prevent the identification of communities or demographics that could benefit most from targeted vaccination outreach.

In an accompanying editorial, Jeanne Marrazzo, CEO of the Infectious Disease Society of America and former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, stated the concern in starker terms, writing: “The evidence is damning: The administration’s anti-vaccine stance has interrupted the reliable flow of the data we need to keep Americans safe from preventable infections. The consequences will be dire.”

The study authors note that the unexplained pauses could be direct targeting of vaccine-related data collection by the administration—or they could be an indirect consequence of the tumult Kennedy and the Trump administration have inflicted on the CDC, including brutal budget and staff cuts. But Marrazzo argues that the exact mechanism doesn’t matter.

“Either causative pathway demonstrates a profound disregard for human life, scientific progress, and the dedication of the public health workforce that has provided a bulwark against the advance of emerging, and reemerging, infectious diseases,” she writes.

Marrazzo emphasizes that the lack of current data not only hampers outbreak response efforts but also helps the health secretary realize his vision for the CDC.

Kennedy, “who has stated baldly that the CDC failed to protect Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, is now enacting a self-fulfilling prophecy. The CDC as it currently exists is no longer the stalwart, reliable source of public health data that for decades has set the global bar for rigorous public health practice.”

Emily Hilliard, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, sent Ars Technica a statement saying: “Changes to individual dashboards or update schedules reflect routine data quality and system management decisions, not political direction. Under this administration, public health data reporting is driven by scientific integrity, transparency, and accuracy.”

Dozens of CDC vaccination databases have been frozen under RFK Jr. Read More »