With new agent mode for Excel and Word, Microsoft touts “vibe working”

With a new set of Microsoft 365 features, knowledge workers will be able to generate complex Word documents or Excel spreadsheets using only text prompts to Microsoft’s chat bot. Two distinct products were announced, each using different models and accessed from within different tools—though the similar names Microsoft chose make it confusing to parse what’s what.

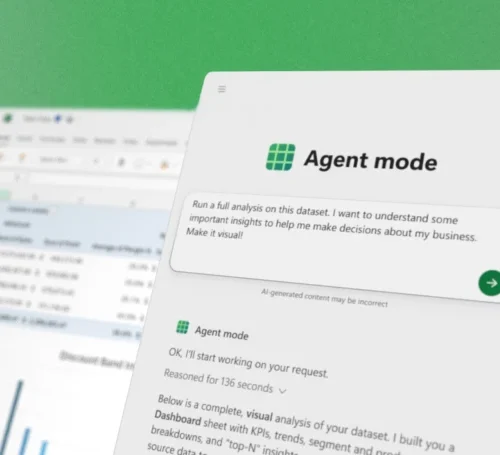

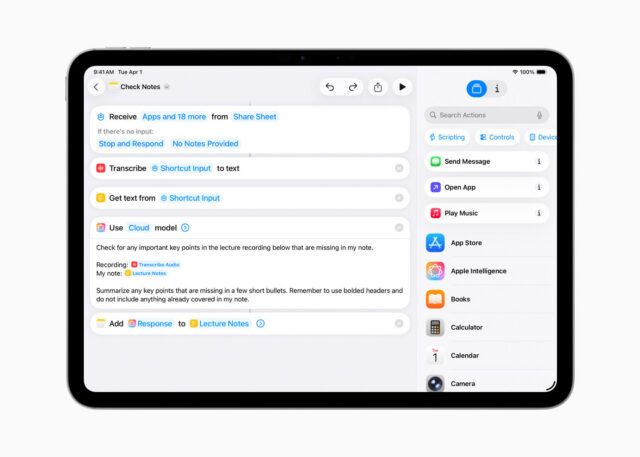

Driven by OpenAI’s GPT-5 large language model, Agent Mode is built into Word and Excel, and it allows the creation of complex documents and spreadsheets from user prompts. It’s called “agent” mode because it doesn’t just work from the prompt in a single step; rather, it plans multi-step work and runs a validation loop in the hopes of ensuring quality.

It’s only available in the web versions of Word and Excel at present, but the plan is to bring it to native desktop applications later.

There’s also the similarly named Office Agent for Copilot. Based on Anthropic models, this feature is built into Microsoft’s Copilot AI assistant chatbot, and it too can generate documents from prompts—specifically, Word or PowerPoint files.

Office Agent doesn’t run through all the steps as Agent Mode, but Microsoft believes it offers a dramatic improvement over prior, OpenAI-driven document-generation capabilities in Copilot, which users complained were prone to all sorts of problems and shortcomings. It is available first in the Frontier Program for Microsoft 365 subscribers.

Together, Microsoft says these features will let knowledge workers engage in a practice it’s calling “vibe working,” a play on the now-established term vibe coding.

Vibe everything, apparently

Vibe coding is the process of developing an application entirely via LLM chatbot prompts. You explain what you want in the chat interface and ask for it to generate code that does that. You then run that code, and if there are problems, explain the problem and tell it to fix it, iterating along the way until you have a usable application.

With new agent mode for Excel and Word, Microsoft touts “vibe working” Read More »