After another Boeing letdown, NASA isn’t ready to buy more Starliner missions

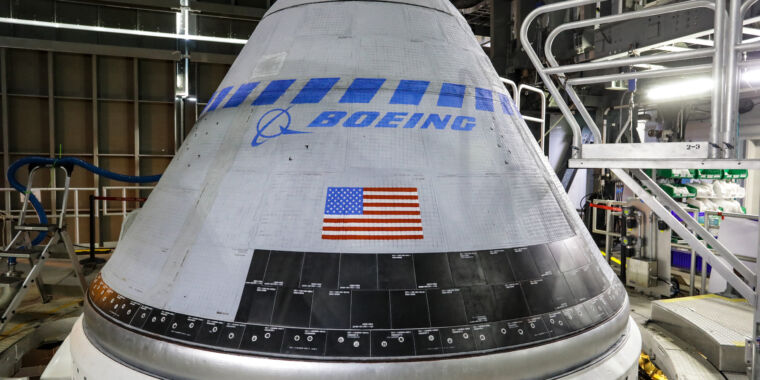

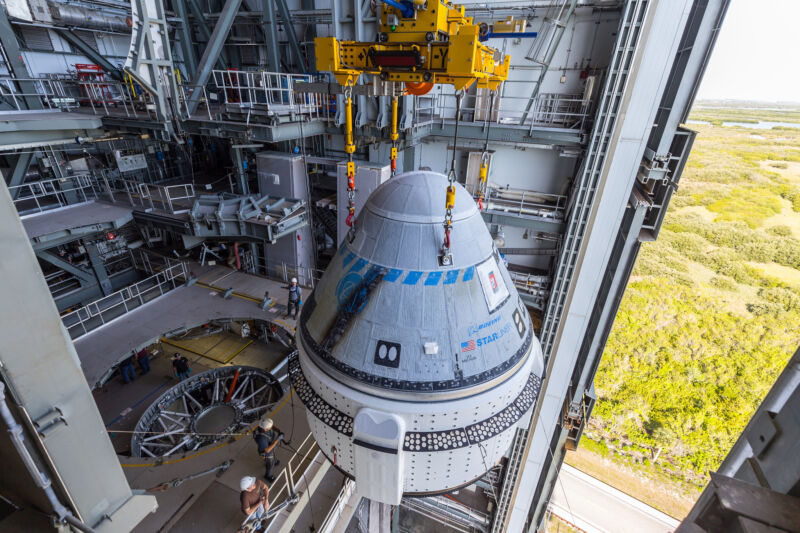

Enlarge / Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft sits atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket before liftoff in June to begin the Crew Flight Test.

NASA is ready for Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft, stricken with thruster problems and helium leaks, to leave the International Space Station as soon as Friday, wrapping up a disappointing test flight that has clouded the long-term future of the Starliner program.

Astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who launched aboard Starliner on June 5, closed the spacecraft’s hatch Thursday in preparation for departure Friday. But it wasn’t what they envisioned when they left Earth on Starliner three months ago. Instead of closing the hatch from a position in Starliner’s cockpit, they latched the front door to the spacecraft from the space station’s side of the docking port.

The Starliner spacecraft is set to undock from the International Space Station at 6: 04 pm EDT (22: 04 UTC) Friday. If all goes according to plan, Starliner will ignite its braking rockets at 11: 17 pm EDT (03: 17 UTC) for a minute-long burn to target a parachute-assisted, airbag-cushioned landing at White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico, at 12: 03 am EDT (04: 03 UTC) Saturday.

The Starliner mission set to conclude this weekend was the spacecraft’s first test flight with astronauts, running seven years behind Boeing’s original schedule. But due to technical problems with the spacecraft, it won’t come home with the two astronauts who flew it into orbit back in June, leaving some of the test flight’s objectives incomplete.

This outcome is, without question, a setback for NASA and Boeing, which must resolve two major problems in Starliner’s propulsion system—supplied by Aerojet Rocketdyne—before the capsule can fly with people again. NASA officials haven’t said whether they will require Boeing to launch another Starliner test flight before certifying the spacecraft for the first of up to six operational crew missions on Boeing’s contract.

A noncommittal from NASA

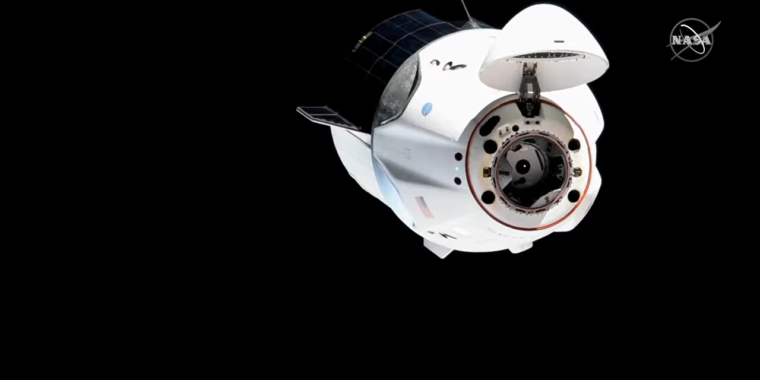

For over a decade, the space agency has worked with Boeing and SpaceX to develop two independent vehicles to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station (ISS). SpaceX launched its first Dragon spacecraft with astronauts in May 2020, and six months later, NASA cleared SpaceX to begin flying regular six-month space station crew rotation missions.

Officially, NASA has penciled in Starliner’s first operational mission for August 2025. But the agency set that schedule before realizing Boeing and Aerojet Rocketdyne would need to redesign seals and perhaps other elements in Starliner’s propulsion system.

No one knows how long that will take, and NASA hasn’t decided if it will require Boeing to launch another test flight before formally certifying Starliner for operational missions. If Starliner performs flawlessly after undocking and successfully lands this weekend, perhaps NASA engineers can convince themselves Starliner is good to go for crew rotation flights once Boeing resolves the thruster problems and helium leaks.

In any event, the schedule for launching an operational Starliner crew flight in less than a year seems improbable. Aside from the decision on another test flight, the agency also must decide whether it will order any more operational Starliner missions from Boeing. These “post-certification missions” will transport crews of four astronauts between Earth and the ISS, orbiting roughly 260 miles (420 kilometers) above the planet.

NASA has only given Boeing the “Authority To Proceed” for three of its six potential operational Starliner missions. This milestone, known as ATP, is a decision point in contracting lingo where the customer—in this case, NASA—places a firm order for a deliverable. NASA has previously said it awards these task orders about two to three years prior to a mission’s launch.

Josh Finch, a NASA spokesperson, told Ars that the agency hasn’t made any decisions on whether to commit to any more operational Starliner missions from Boeing beyond the three already on the books.

“NASA’s goal remains to certify the Starliner system for crew transportation to the International Space Station,” Finch said in a written response to questions from Ars. “NASA looks forward to its continued work with Boeing to complete certification efforts after Starliner’s uncrewed return. Decisions and timing on issuing future authorizations are on the work ahead.”

This means NASA’s near-term focus is on certifying Starliner so that Boeing can start executing its commercial crew contract. The space agency hasn’t determined when or if it will authorize Boeing to prepare for any Starliner missions beyond the three already on the books.

When it awarded commercial crew contracts to SpaceX and Boeing in 2014, NASA pledged to buy at least two operational crew flights from each company. The initial contracts from a decade ago had options for as many as six crew rotation flights to the ISS after certification.

Since then, NASA has extended SpaceX’s commercial crew contract to cover as many as 14 Dragon missions with astronauts, and SpaceX has already launched eight of them. The main reason for this contract extension was to cover NASA’s needs for crew transportation after delays with Boeing’s Starliner, which was originally supposed to alternate with SpaceX’s Dragon for human flights every six months.

After another Boeing letdown, NASA isn’t ready to buy more Starliner missions Read More »