SpaceX launches a pair of NASA satellites to probe the origins of space weather

“This is going to really help us understand how to predict space weather in the magnetosphere.”

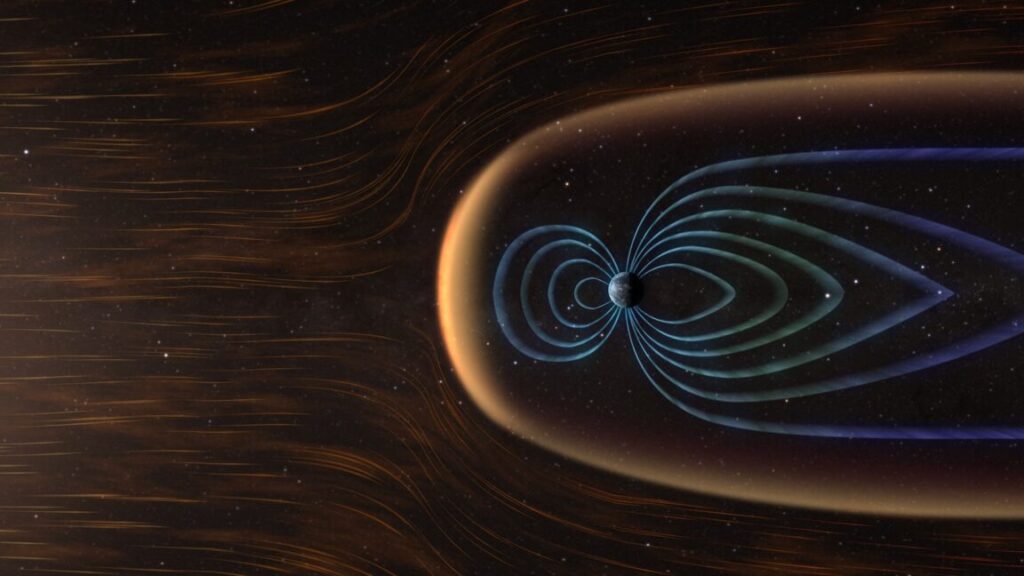

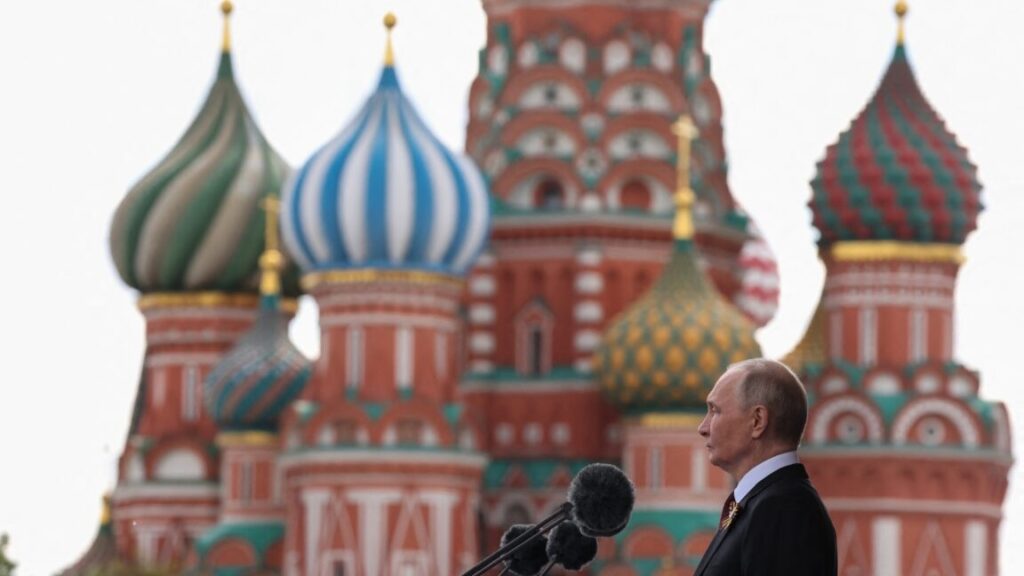

This artist’s illustration of the Earth’s magnetosphere shows the solar wind (left) streaming from the Sun, and then most of it being blocked by Earth’s magnetic field. The magnetic field lines seen here fold in toward Earth’s surface at the poles, creating polar cusps. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Two NASA satellites rocketed into orbit from California aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket Wednesday, commencing a $170 million mission to study a phenomenon of space physics that has eluded researchers since the dawn of the Space Age.

The twin spacecraft are part of the NASA-funded TRACERS mission, which will spend at least a year measuring plasma conditions in narrow regions of Earth’s magnetic field known as polar cusps. As the name suggests, these regions are located over the poles. They play an important but poorly understood role in creating colorful auroras as plasma streaming out from the Sun interacts with the magnetic field surrounding Earth.

The same process drives geomagnetic storms capable of disrupting GPS navigation, radio communications, electrical grids, and satellite operations. These outbursts are usually triggered by solar flares or coronal mass ejections that send blobs of plasma out into the Solar System. If one of these flows happens to be aimed at Earth, we are treated with auroras but vulnerable to the storm’s harmful effects.

For example, an extreme geomagnetic storm last year degraded GPS navigation signals, resulting in more than $500 million in economic losses in the agriculture sector as farms temporarily suspended spring planting. In 2022, a period of elevated solar activity contributed to the loss of 40 SpaceX Starlink satellites.

“Understanding our Sun and the space weather it produces is more important to us here on Earth, I think, than most realize,” said Joe Westlake, director of NASA’s heliophysics division.

NASA’s two TRACERS satellites launched Wednesday aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California. Credit: SpaceX

The launch of TRACERS was delayed 24 hours after a regional power outage disrupted air traffic control over the Pacific Ocean near the Falcon 9 launch site on California’s Central Coast, according to the Federal Aviation Administration. SpaceX called off the countdown Tuesday less than a minute before liftoff, then rescheduled the flight for Wednesday.

TRACERS, short for Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites, will study a process known as magnetic reconnection. As particles in the solar wind head out into the Solar System at up to 1 million mph, they bring along pieces of the Sun’s magnetic field. When the solar wind reaches our neighborhood, it begins interacting with Earth’s magnetic field.

The high-energy collision breaks and reconnects magnetic field lines, flinging solar wind particles across Earth’s magnetosphere at speeds that can approach the speed of light. Earth’s field draws some of these particles into the polar cusps, down toward the upper atmosphere. This is what creates dazzling auroral light shows and potentially damaging geomagnetic storms.

Over our heads

But scientists still aren’t sure how it all works, despite the fact that it’s happening right over our heads, within the reach of countless satellites in low-Earth orbit. But a single spacecraft won’t do the job. Scientists need at least two spacecraft, each positioned in bespoke polar orbits and specially instrumented to measure magnetic fields, electric fields, electrons, and ions.

That’s because magnetic reconnection is a dynamic process, and a single satellite would provide just a snapshot of conditions over the polar cusps every 90 minutes. By the time the satellite comes back around on another orbit, conditions will have changed, but scientists wouldn’t know how or why, according to David Miles, principal investigator for the TRACERS mission at the University of Iowa.

“You can’t tell, is that because the system itself is changing?” Miles said. “Is that because this magnetic reconnection, the coupling process, is moving around? Is it turning on and off, and if it’s turning on and off, how quickly can it do it? Those are fundamental things that we need to understand… how the solar wind arriving at the Earth does or doesn’t transfer energy to the Earth system, which has this downstream effect of space weather.”

This is why the tandem part of the TRACERS name is important. The novel part of this mission is it features two identical spacecraft, each about the size of a washing machine flying at an altitude of 367 miles (590 kilometers). Over the course of the next few weeks, the TRACERS satellites will drift into a formation with one trailing the other by about two minutes as they zip around the world at nearly five miles per second. This positioning will allow the satellites to sample the polar cusps one right after the other, instead of forcing scientists to wait another 90 minutes for a data refresh.

With TRACERS, scientists hope to pick apart smaller, fast-moving changes with each satellite pass. Within a year, TRACERS should collect 3,000 measurements of magnetic reconnections, a sample size large enough to start identifying why some space weather events evolve differently than others.

“Not only will it get a global picture of reconnection in the magnetosphere, but it’s also going to be able to statistically study how reconnection depends on the state of the solar wind,” said John Dorelli, TRACERS mission scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “This is going to really help us understand how to predict space weather in the magnetosphere.”

One of the two TRACERS satellites undergoes launch preparations at Millennium Space Systems, the spacecraft’s manufacturer. Credit: Millennium Space Systems

“If we can understand these various different situations, whether it happens suddenly if you have one particular kind of event, or it happens in lots of different places, then we have a better way to model that and say, ‘Ah, here’s the likelihood of seeing a certain kind of effect that would affect humans,'” said Craig Kletzing, the principal investigator who led the TRACERS science team until his death in 2023.

There is broader knowledge to be gained with a mission like TRACERS. Magnetic reconnection is ubiquitous throughout the Universe, and the same physical processes produce solar flares and coronal mass ejections from the Sun.

Hitchhiking to orbit

Several other satellites shared the ride to space with TRACERS on Wednesday.

These secondary payloads included a NASA-sponsored mission named PExT, a small technology demonstration satellite carrying an experimental communications package capable of connecting with three different networks: NASA’s government-owned Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS) and commercial satellite networks owned by SES and Viasat.

What’s unique about the Polylingual Experimental Terminal, or PExT, is its ability to roam across multiple satellite relay networks. The International Space Station and other satellites in low-Earth orbit currently connect to controllers on the ground through NASA’s TDRS satellites. But NASA will retire its TDRS satellites in the 2030s and begin purchasing data relay services using commercial satellite networks.

The space agency expects to have multiple data relay providers, so radios on future NASA satellites must be flexible enough to switch between networks mid-mission. PExT is a pathfinder for these future missions.

Another NASA-funded tech demo named Athena EPIC was also aboard the Falcon 9 rocket. Led by NASA’s Langley Research Center, this mission uses a scalable satellite platform developed by a company named NovaWurks, using building blocks to piece together everything a spacecraft needs to operate in space.

Athena EPIC hosts a single science instrument to measure how much energy Earth radiates into space, an important data point for climate research. But the mission’s real goal is to showcase how an adaptable satellite design, such as this one using NovaWurks’ building block approach, might be useful for future NASA missions.

A handful of other payloads rounded out the payload list for Wednesday’s launch. They included REAL, a NASA-funded CubeSat project to investigate the Van Allen radiation belts and space weather, and LIDE, an experimental 5G communications satellite backed by the European Space Agency. Five commercial spacecraft from the Australian company Skykraft also launched to join a constellation of small satellites to provide tracking and voice communications between air traffic controllers and aircraft over remote parts of the world.

SpaceX launches a pair of NASA satellites to probe the origins of space weather Read More »