With GPT-5.3-Codex, OpenAI pitches Codex for more than just writing code

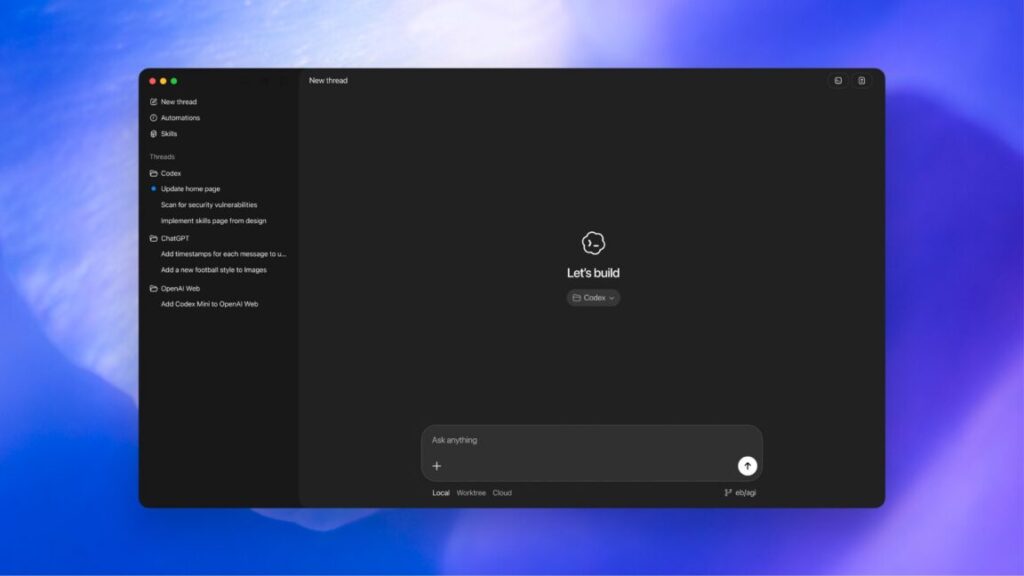

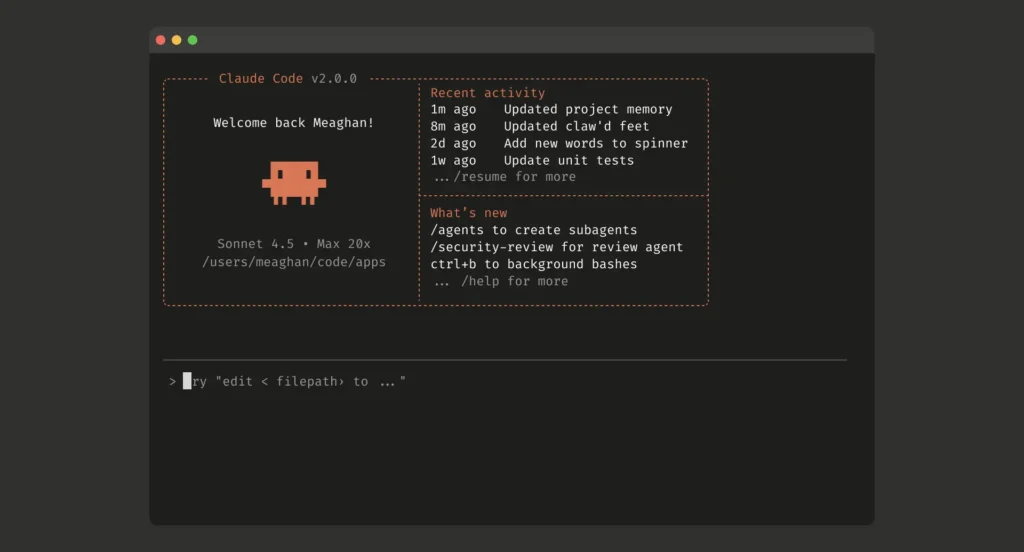

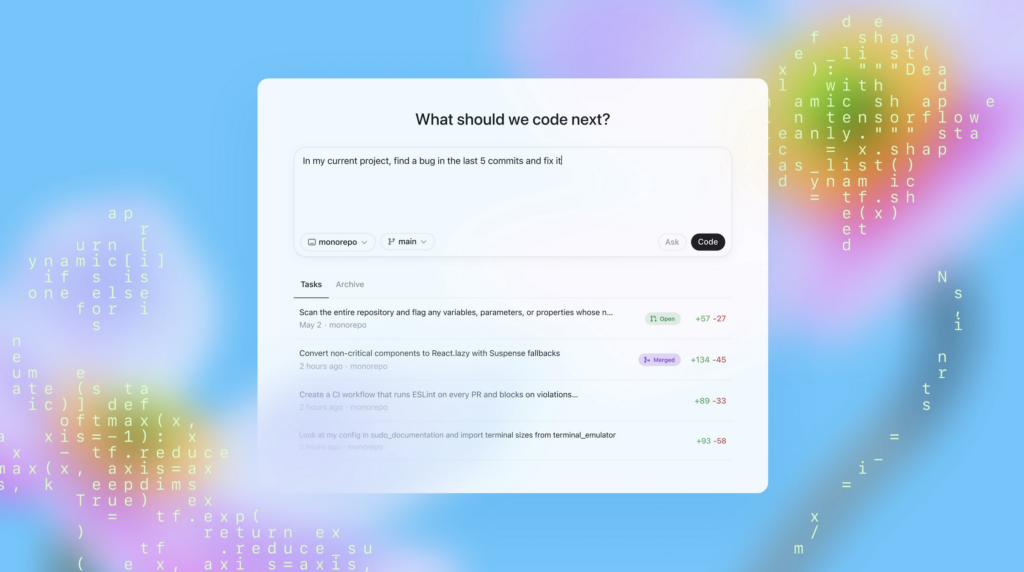

Today, OpenAI announced GPT-5.3-Codex, a new version of its frontier coding model that will be available via the command line, IDE extension, web interface, and the new macOS desktop app. (No API access yet, but it’s coming.)

GPT-5.3-Codex outperforms GPT-5.2-Codex and GPT-5.2 in SWE-Bench Pro, Terminal-Bench 2.0, and other benchmarks, according to the company’s testing.

There are already a few headlines out there saying “Codex built itself,” but let’s reality-check that, as that’s an overstatement. The domains OpenAI described using it for here are similar to the ones you see in some other enterprise software development firms now: managing deployments, debugging, and handling test results and evaluations. There is no claim here that GPT-5.3-Codex built itself.

Instead, OpenAI says GPT-5.3-Codex was “instrumental in creating itself.” You can read more about what that means in the company’s blog post.

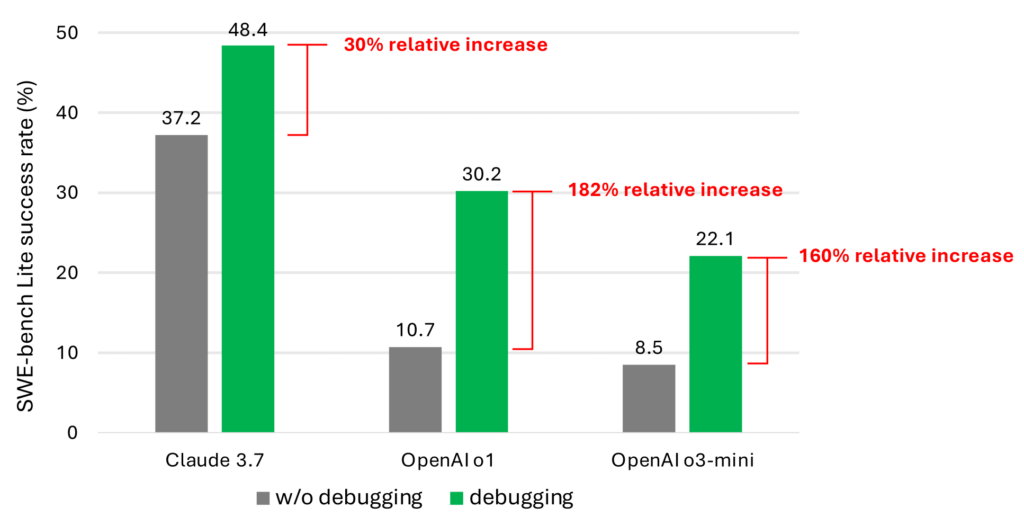

But that’s part of the pitch with this model update—OpenAI is trying to position Codex as a tool that does more than generate lines of code. The goal is to make it useful for “all of the work in the software lifecycle—debugging, deploying, monitoring, writing PRDs, editing copy, user research, tests, metrics, and more.” There’s also an emphasis on steering the model mid-task and frequent status updates.

With GPT-5.3-Codex, OpenAI pitches Codex for more than just writing code Read More »