Once unthinkable, NASA and Lockheed now consider launching Orion on other rockets

“We’re trying to crawl, then walk, then run into our reuse strategy.”

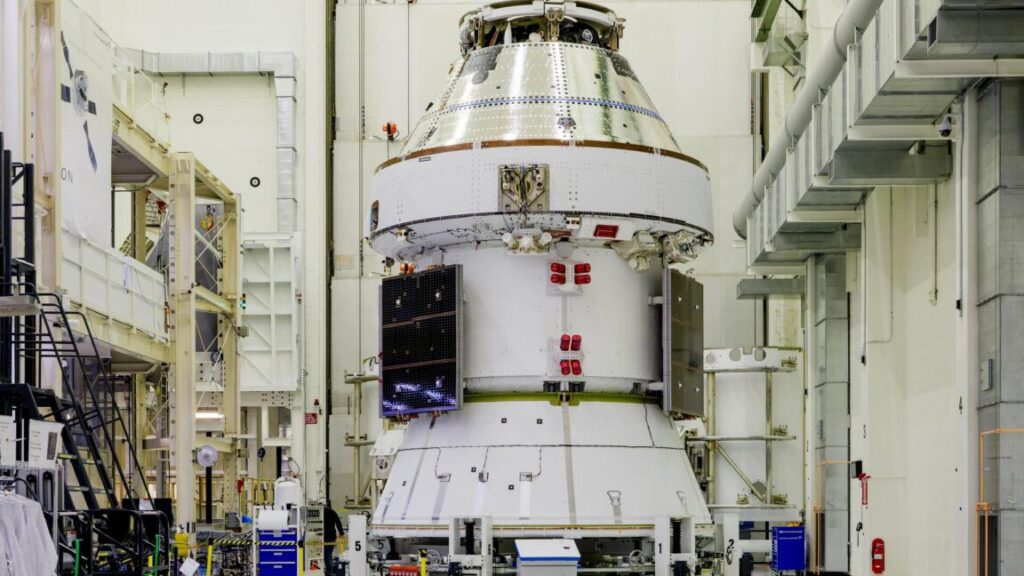

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis II mission, seen here with its solar arrays installed for flight, just prior to their enclosure inside aerodynamic fairings to protect them during launch. Credit: NASA/Rad Sinyak

The Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System rocket have been attached at the hip for the better part of two decades. The big rocket lifts, the smaller spacecraft flies, and Congress keeps the money rolling in.

But now there are signs that the twain may, in the not too distant future, split.

This is because Lockheed Martin has begun to pivot toward a future in which the Orion spacecraft—thanks to increasing reusability, a focus on cost, and openness to flying on different rockets—fits into commercial space applications. In interviews, company officials said that if NASA wanted to buy Orion missions as a “service,” rather than owning and operating the spacecraft, they were ready to work with the space agency.

“Our message is we absolutely support it, and we’re starting that discussion now,” said Anthony Byers, director of Strategy and Business Development for Lockheed Martin, the principal contractor for Orion.

This represents a significant change. Since the US Congress called for the creation of the Space Launch System rocket a decade and a half ago, Orion and this rocket have been discussed in tandem, forming the backbone of an expendable architecture that would launch humans to the Moon and return them to Earth inside Orion. Through cost-plus contracts, NASA would pay for the rockets and spacecraft to be built, closely supervise all of this, and then operate the vehicles after delivery.

Moving to a ‘services’ model

But the landscape is shifting. In President Trump’s budget request for fiscal year 2026, the White House sought to terminate funding for Orion and the SLS rocket after the Artemis III mission, which would mean there are just two flights remaining. Congress countered by saying that NASA should continue flying the spacecraft and rocket through Artemis V.

Either way, the writing on the wall seems pretty clear.

“Given the President’s Budget Request guidance, and what we think NASA’s ultimate direction will be, they’re going to need to move to a commercial transportation option similar to commercial crew and cargo,” Byers said. “So when we talk about Orion services, we’re talking about taking Orion and flying that service-based mission, which means we provide a service, from boots on the ground on Earth, to wherever we’re going to go and dock to, and then bringing the crew home.”

By contrast, there has been little movement on an effort to commercialize the rocket.

In 2022, Boeing, the contractor for the SLS core stage, and Northrop Grumman, which manufactures the side boosters, created “Deep Space Transport LLC” to build the rockets and sell them to NASA on a more services-based approach. However, despite NASA’s stated intent to award a launch services contract to Deep Space Transport by the end of 2023, no such contract has been given out. It appears that the joint venture to commercialize the SLS rocket is defunct. Moreover, there are no plans to modify the rocket for reuse.

Wanted: a heavy lift rocket

This appears to be one reason Lockheed is exploring alternative launch vehicles for Orion. If the spacecraft is going to be competitive on price, it needs a rocket that does not cost in excess of $2 billion per launch.

Orion has a launch mass, including its abort system, of 35 metric tons. The company has looked at rockets that could launch that much mass and boost it to the Moon, as well as alternatives that might see one rocket launch Orion, and another provide a tug vehicle to push it out to the Moon. So far, the company has not advanced to performing detailed studies of vibrations, acoustics, thermal loads, and other assessments of compatibility, said Kirk Shireman, Lockheed Martin’s vice president and program manager for Orion.

“Could you create architectures to fly on other vehicles? Yes, we know we can,” Shireman said. “But when you start talking about those other environmental things, we have not done any of that work.”

So what else is being done to control Orion’s costs? Lockheed officials said incorporating reuse into Orion’s plans is “absolutely critical.” This is a philosophy that has evolved over time, especially after SpaceX began reflying its Dragon spacecraft.

NASA first contracted with Lockheed nearly two decades ago to start preliminary development work on Orion. At the outset, spacecraft reuse was not a priority. Byers, who has been involved with the Orion program at Lockheed on and off since its inception, said initially NASA asked Lockheed to assess the potential for reusing components of Orion.

“Whenever the vehicle would come back, NASA’s assumption was that we would disassemble the vehicle and harvest the components, and they would go into inventory,” Byers said. “Then they would go into a new structure for a future flight. Well, as the program progressed and we saw what others were doing, we really started to introduce the idea of reusing the crew module.”

How to reuse a spacecraft

The updated plan agreed to by NASA and Lockheed calls for a step-by-step approach.

“There’s a path forward,” said Howard Hu, NASA’s Orion program manager, in an interview. “We’re trying to crawl, then walk, then run into our reuse strategy. We want to make sure that we’re increasing our reusability, which we know is the path to sustainability and lower cost.”

The current plan is as follows:

Artemis II: A brand-new spacecraft, it will reuse 11 avionics components refurbished from the Artemis I Orion spacecraft; after landing, it will be used for testing purposes.

Artemis III: A brand-new spacecraft.

Artemis IV: A brand-new spacecraft.

Artemis V: Will reuse approximately 250 components, primarily life support and avionics equipment, from Artemis II.

Artemis VI: Will reuse primary structure (pressure vessel) and secondary structures (gussets, panels, brackets, plates) from Artemis III Orion, and approximately 3,000 components.

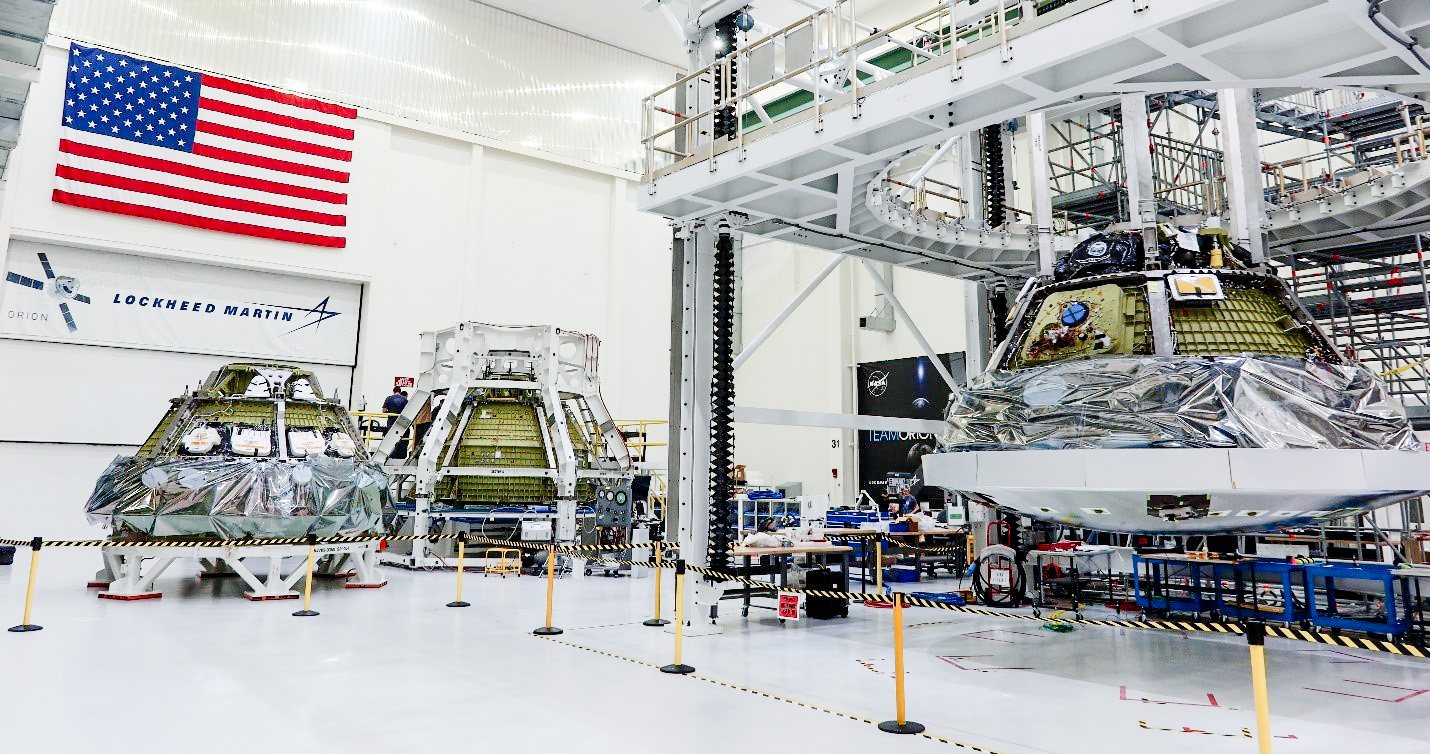

Lockheed plans to build a fleet of three largely reusable spacecraft, which will make their debuts on the Artemis III, IV, and V missions, respectively. Those three vehicles would then fly future missions, and if Lockheed needs to expand the fleet to meet demand, it could.

This photo, from 2023, shows the Orions for Artemis II, III, and IV all together. Credit: Lockheed Martin

Of course, Orion can never be made fully reusable. The service module, built by Europe-based Airbus and providing propulsion, separates from Orion before reentry into Earth’s atmosphere and burns up.

“We probably should call it maximum reuse, because there are some things that are consumed,” Shireman said. “For instance, the heat shield is consumed as the ablative material is ablated. But we are, ultimately, going to reuse the structure of the heat shield itself.”

Vectoring along a new path

Orion is always going to be relatively expensive. However, officials said they are on track to trim the cost of producing an Orion by 50 percent from the Artemis II to Artemis V vehicles and in follow-on missions to bring this down by 30 percent further or more. Minimizing refurbishment will be key to this.

Lockheed will never achieve “full and rapid reusability” for Orion like SpaceX is attempting with its Starship vehicle. That’s just not the way Orion was designed, nor what NASA wants. The space agency seeks a safe and reliable ride into deep space for its astronauts.

For the time being, only Orion can provide that. In the future, Starship may well provide that capability. Blue Origin and other providers may develop a deep space-capable human vehicle. But Orion is here and ready for its first astronauts in 2026. It will be years before any alternative becomes available.

It is nice to see that Lockheed recognizes this advantage won’t last forever and that it’s moving—or should we say, Vectoring—toward a more sustainable future.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

Once unthinkable, NASA and Lockheed now consider launching Orion on other rockets Read More »