Trump executive order calls for a next-generation missile defense shield

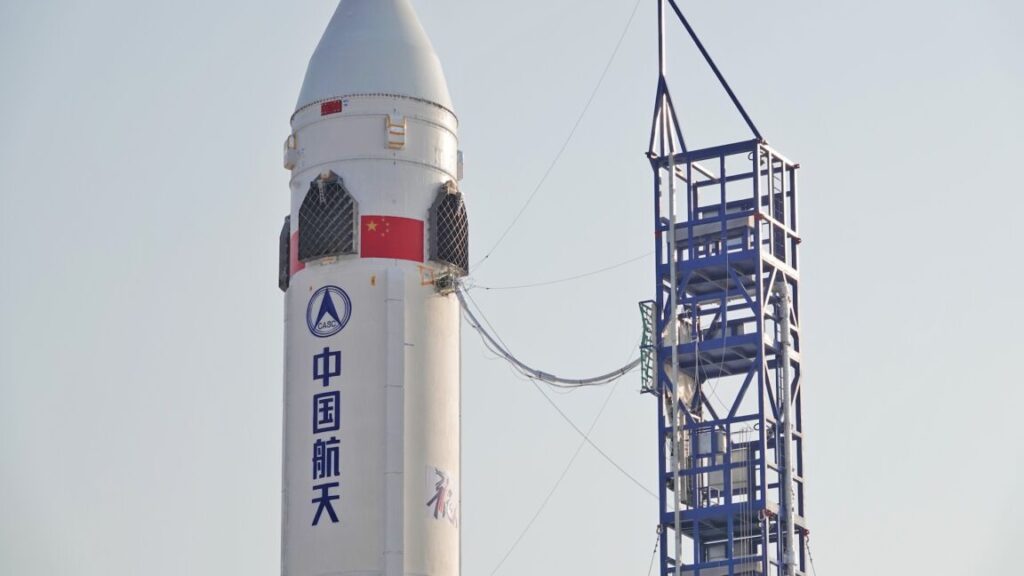

One of the new Trump administration’s first national security directives aims to defend against missile and drone attacks targeting the United States, and several elements of the plan require an expansion of the US military’s presence in space, the White House announced Monday.

For more than 60 years, the military has launched reconnaissance, communications, and missile warning satellites into orbit. Trump’s executive order calls for the Pentagon to come up with a design architecture, requirements, and an implementation plan for the next-generation missile defense shield within 60 days.

A key tenet of Trump’s order is to develop and deploy space-based interceptors capable of destroying enemy missiles during their initial boost phase shortly after launch.

“The United States will provide for the common defense of its citizens and the nation by deploying and maintaining a next-generation missile defense shield,” the order reads. “The United States will deter—and defend its citizens and critical infrastructure against—any foreign aerial attack on the homeland.”

The White House described the missile defense shield as an “Iron Dome for America,” referring to the name of Israel’s regional missile defense system. While Israel’s Iron Dome is tailored for short-range missiles, the White House said the US version will guard against all kinds of airborne attacks.

What does the order actually say?

Trump’s order is prescriptive in what to do, but it leaves the implementation up to the Pentagon. The White House said the military’s plan must defend against many types of aerial threats, including ballistic, hypersonic, and advanced cruise missiles, plus “other next-generation aerial attacks,” a category that appears to include drones and shorter-range unguided missiles.

Trump executive order calls for a next-generation missile defense shield Read More »