Pentagon buyer: We’re happy with our launch industry, but payloads are lagging

“The point is to get missions out the door as fast as possible. Two to three years is too slow.”

Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy oversees the Space Force’s acquisition programs at the Pentagon. Credit: Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post via Getty Images

DALLAS—The Space Force officer tasked with overseeing more than $24 billion in research and development spending says the Pentagon is more interested in supporting startups building new space sensors and payloads than adding yet another rocket company to its portfolio.

The statement, made at a space finance conference in Dallas last week, was one of several points Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy wanted to get across to a room full of investors and commercial space executives.

The other points on Purdy’s agenda were that the Space Force is more interested in high-volume production than spending money to develop the latest technologies, and that the military has, at least for now, lost one of its most important tools for supporting and diversifying the space industrial base.

The rhetoric around prioritizing payloads over launchers aligns with the Space Force’s recent history of supporting small startups. Since 2020, SpaceWERX, the Space Force’s commercial innovation program, has awarded 23 funding agreements—called Strategic Funding Increases (STRATFIs)—to commercial space startups developing new sensors, software, satellite components, spacecraft buses, and orbital transfer vehicles. SpaceWERX awarded a single STRATFI agreement to a launch company—ABL Space Systems—and that firm has since exited the space launch market.

“We’re on path for mass-produced launch,” said Purdy, the military deputy for space acquisition in the Department of the Air Force. “We have got our ranges situated so we can do mass-produced launch. We’ve got our data centers and our data structure for mass-production. We’ve got AI pieces that are mass-produced, satellite buses are nearly there, and our payloads are the last element. Payloads at mass-produced affordability, at scale, is the key element.”

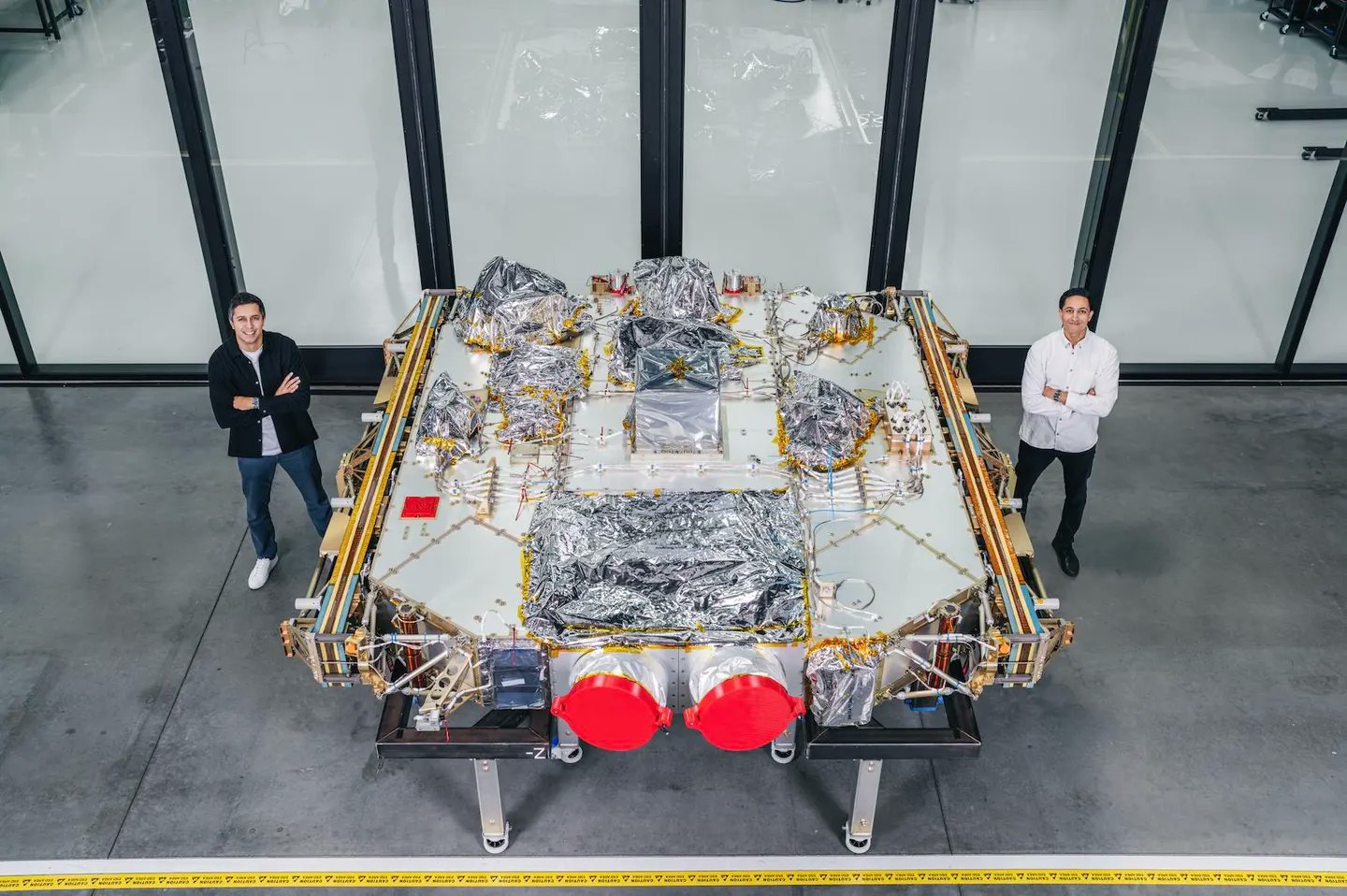

K2’s Gravitas satellite, set for launch next month, will test the company’s Hall-effect thruster, solar arrays, and other systems. Credit: K2

Putting the money in

Payloads, Purdy told Ars after his talk, are “the last frontier” for scaling space missions. “The point is to get missions out the door as fast as possible. Two to three years is too slow. We’ve got to get down to one week. I’m not talking about super exquisite [payloads]. That’s not most of our missions. The commercial industry, your Kuipers [Amazon LEO], your Starlinks, have sort of got the comm piece down, but we’re still struggling in a lot of other stuff.”

One kind of payload Purdy identified was infrared sensors. Infrared sensors often come with cryocoolers to chill detectors to temperatures cold enough to provide sensitivity to faint targets, such as distant missile plumes, fires, explosions, or other objects in space. The technology isn’t as eye-catching as a rocket launch, but it will be key to many Space Force programs, including the Golden Dome missile defense shield backed by the Trump administration.

“I remain convinced that we’re going to think about the mission that we need, and we’re going to need satellites out the door and launched and in orbit within the week, at scale,” Purdy said. “I’m very convinced that that’s the path that we’re going to move down on the commercial and government side.”

The companies that come closest to that pace of satellite manufacturing are the ones Purdy mentioned: SpaceX’s Starlink and the Amazon LEO broadband networks. SpaceX and Amazon produce multiple satellites per day, but the spacecraft are identical. The Space Force needs plenty of rockets and communications satellites, but it also needs payloads and sensors to ride those launch vehicles and produce the data to be routed through relay stations in orbit.

Before President Trump ever uttered the words “Golden Dome,” the Space Force’s Space Development Agency was already striving to deploy a network of at least several hundred government-owned missile-detection, tracking, and data-relay satellites. Those satellites have suffered delays due to supply chain issues, particularly long lead times and delays in satellite buses, infrared payloads, laser communication terminals, and radiation-hardened processors.

Singing the blues

But the Space Force has lost access to one of the tools it used to help solve these problems. Many space mission components come from small businesses, and some parts come from overseas. The Space Force used STRATFIs, Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants to pay companies for basic research, experimentation, and scaling up manufacturing capacity. STRATFIs, SBIRs, and STTRs provided seed funding for high-risk, high-reward research and development.

Congress last year failed to reauthorize these programs, which are also used by NASA and other federal agencies. Opponents to a clean extension wanted legislation to cap how much funding can go to each grant recipient.

“I’ve got to get SBIRs and STRATFIs reauthorized, so I need the community’s help to get that done,” Purdy said. “There are some valid concerns that need to be addressed. All that needs to be addressed, but it affects the space industrial base a lot more than the other areas, and so I need everyone to kind of pile on and help get that done.”

Purdy took a victory lap by listing several STRATFIs that have, so far, yielded major results, at least for investors. K2 Space, a company developing high-power, low-cost satellite platforms, received $30 million in funding from the Space Force and Air Force in 2024. A year later, K2 closed a $250 million fundraising round at a company valuation of $3 billion. Apex Space, another startup looking to scale satellite manufacturing, received $11 million in strategic funding in 2024. A year later, Apex became a unicorn, exceeding a valuation of $1 billion. Impulse Space, which is working on in-space propulsion, received a STRATFI funding commitment from the Pentagon in 2024, helping propel the startup to a valuation of $1.8 billion.

“Years of SBIRs and STRATFIs have set the stage … We’ve been doing that for three or four or five years, we’ve produced a nice pool of 60 or 70 different companies that can help bid on all our upcoming new contracts, which is really nice,” Purdy said.

Under the Trump administration, the Defense Department has taken more steps to get cash in the hands of defense contractors. The Pentagon announced last month a $1 billion “direct-to-supplier” investment in L3Harris to expand production capacity of US solid rocket motors. This gives the federal government a direct equity stake in L3Harris’s missile business.

A Trump executive order last month also excoriated the defense industry for ballooning executive salaries, stock buybacks, and systemic lethargy. “You see some strong language through executive order and other mechanisms to say, ‘Hey, companies, you need to put in more CapEx yourselves. You need to kick in more yourselves.’ We’re no longer just going to provide you billions of dollars just for you to go build buildings,” Purdy said.

“And there’s some threat language on the back end of that. You’re going to do that, or else we’re going to start cutting you off. We’re going to start looking at other providers. That’s out in the open and subject for debate. But there’s a big carrot coming along with that, and that’s multi-year procurements. Multi-year procurements are the carrot to allow the investing community to have some amount of confidence,” Purdy continued.

“We’re not looking to be your R&D arm.”

Pentagon buyer: We’re happy with our launch industry, but payloads are lagging Read More »