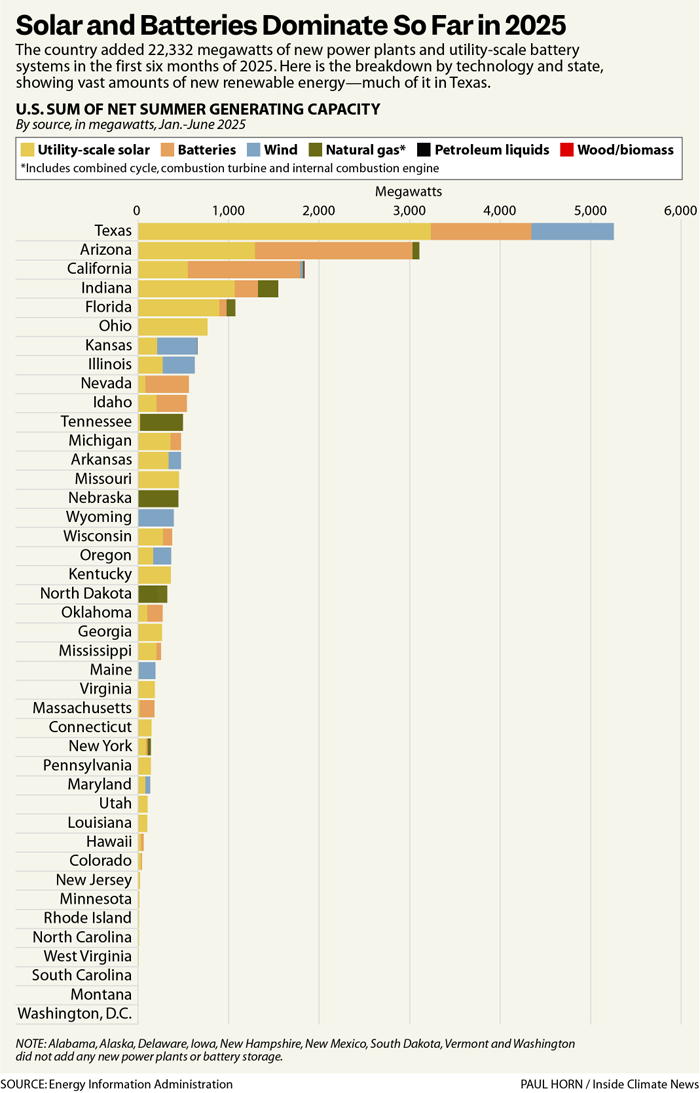

Vast majority of new US power plants generate solar or wind power

But Victor views this as more of a slowdown than a reversal of momentum. One reason is that demand for electricity continues to rise to serve data centers and other large power users. The main beneficiaries are energy technologies that are the easiest to build and most cost effective, including solar, batteries, and gas.

In the first half of this year, the United States added 341 new power plants or utility-scale battery systems, with a total of 22,332 megawatts of summer generating capacity, according to EIA.

Credit: Inside Climate News

More than half the total was utility-scale solar, with 12,034 megawatts, followed by battery systems, with 5,900 megawatts, onshore wind, with 2,697 megawatts, and natural gas, with 1,691 megawatts, which includes several types of natural gas plants.

The largest new plant by capacity was the 600-megawatt Hornet Solar in Swisher County, Texas, which went online in April.

“Hornet Solar is a testament to how large-scale energy projects can deliver reliable, domestic power to American homes and businesses,” said Juan Suarez, co-CEO of the developer, Vesper Energy of the Dallas area, in a statement from the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

The plants being completed now are special in part because of what they have endured, said Ric O’Connell, executive director of GridLab, a nonprofit that does technical analysis for regulators and renewable power advocates. Power plants take years to plan and build, and current projects likely began development during the COVID-19 pandemic. They stayed on track despite high inflation, parts shortages, and challenges in getting approval for grid connections, he said.

“It’s been a rocky road for a lot of these projects, so it’s exciting to see them online,” O’Connell said.

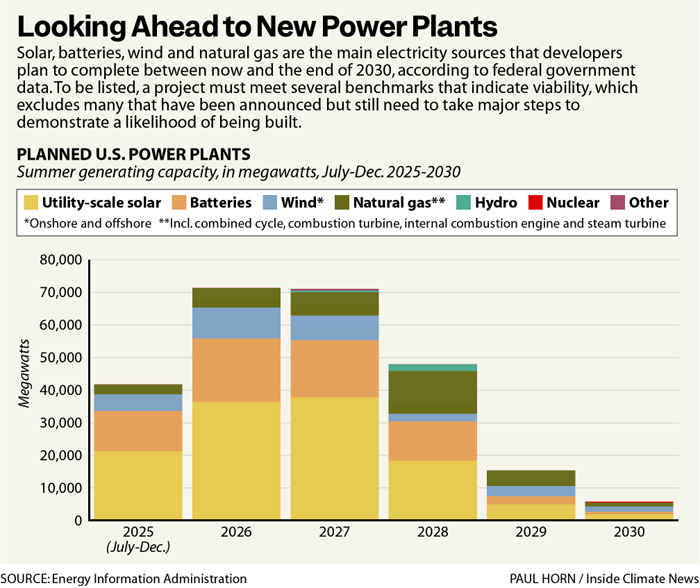

Credit: Inside Climate News

Looking ahead to the rest of this year and through 2030, the country has 254,126 megawatts of planned power plants, according to EIA. (To appear on this list, a project must meet three of four benchmarks: land acquisition, permits obtained, financing received, and a contract completed for selling electricity.)

Solar is the leader with 120,269 megawatts, followed by batteries, with 65,051 megawatts, and natural gas, with 35,081 megawatts.

Vast majority of new US power plants generate solar or wind power Read More »