These scientists explored the good vibrations of the bundengan and didgeridoo

On the fifth day of Christmas —

Their relatively simple construction produces some surprisingly complicated physics.

Enlarge / The bundengan (left) began as a combined shelter/instrument for duck hunters but it is now often played onstage.

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2020, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: the surprisingly complex physics of two simply constructed instruments: the Indonesian bundengan and the Australian Aboriginal didgeridoo (or didjeridu).

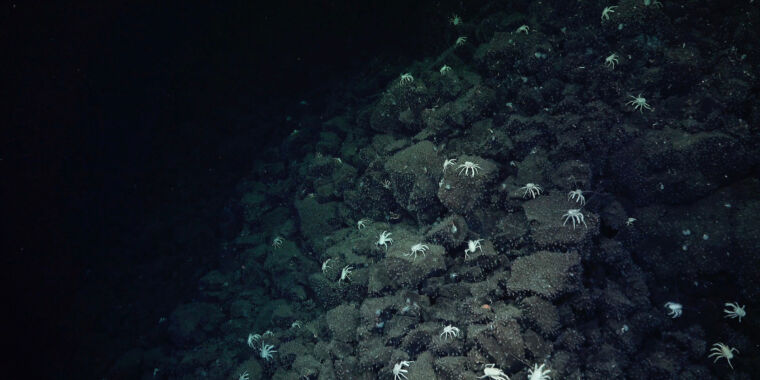

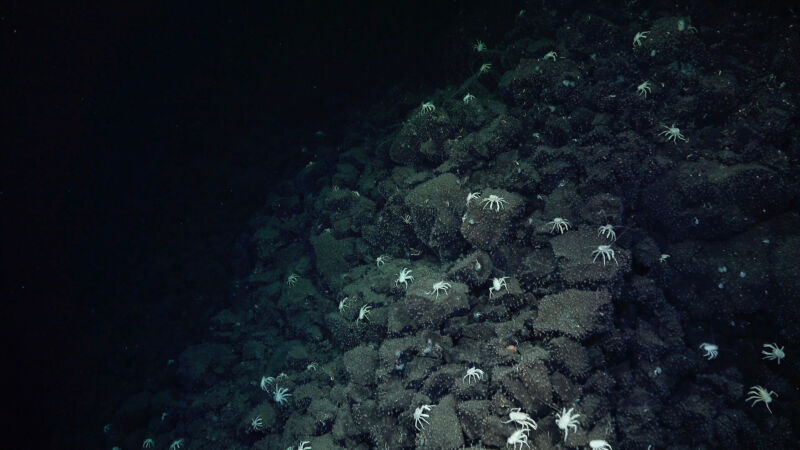

The bundengan is a rare, endangered instrument from Indonesia that can imitate the sound of metallic gongs and cow-hide drums (kendangs) in a traditional gamelan ensemble. The didgeridoo is an iconic instrument associated with Australian Aboriginal culture that produces a single, low-pitched droning note that can be continuously sustained by skilled players. Both instruments are a topic of scientific interest because their relatively simple construction produces some surprisingly complicated physics. Two recent studies into their acoustical properties were featured at an early December meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, held in Sydney, Australia, in conjunction with the Australian Acoustical Society.

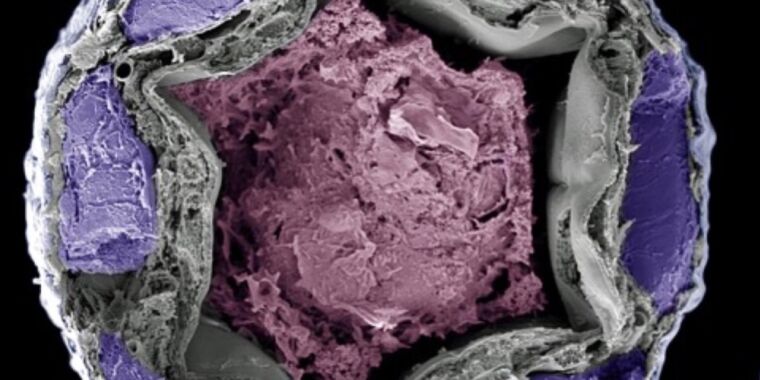

The bundengan originated with Indonesian duck hunters as protection from rain and other adverse conditions while in the field, doubling as a musical instrument to pass the time. It’s a half-dome structure woven out of bamboo splits to form a lattice grid, crisscrossed at the top to form the dome. That dome is then coated with layers of bamboo sheaths held in place with sugar palm fibers. Musicians typically sit cross-legged inside the dome-shaped resonator and pluck the strings and bars to play. The strings produce metallic sounds while the plates inside generate percussive drum-like sounds.

Gea Oswah Fatah Parikesit of Universitas Gadja Mada in Indonesia has been studying the physics and acoustics of the bundengan for several years now. And yes, he can play the instrument. “I needed to learn to do the research,” he said during a conference press briefing. “It’s very difficult because you have two different blocking styles for the right and left hand sides. The right hand is for the melody, for the string, and the left is for the rhythm, to pluck the chords.”

Much of Parikesit’s prior research on the bundengan focused on the unusual metal/percussive sound of the strings, especially the critical role played by the placement of bamboo clips. He used computational simulations of the string vibrations to glean insight on how the specific gong-like sound was produced, and how those vibrations change with the addition of bamboo clips located at different sections of the string. He found that adding the clips produces two vibrations of different frequencies at different locations on the string, with the longer section having a high frequency vibration compared to the lower frequency vibration of the shorter part of the string. This is the key to making the gong-like sound.

This time around, Parikesit was intrigued by the fact many bundengan musicians have noted the instrument sounds better wet. In fact, several years ago, Parikesit attended a bundengan concert in Melbourne during the summer when it was very hot and dry—so much so that the musicians brought their own water spray bottles to ensure the instruments stayed (preferably) fully wet.

Enlarge / A bundengan is a portable shelter woven from bamboo, worn by Indonesian duck herders who often outfit it to double as a musical instrument.

Gea Oswah Fatah Parikesit

“A key element between the dry and wet versions of the bundengan is the bamboo sheaths—the material used to layer the wall of the instrument,” Parokesit said. “When the bundengan is dry, the bamboo sheaths open and that results in looser connections between neighboring sheaths. When the bundengan is wet, the sheaths tend to form a curling shape, but because they are held by ropes, they form tight connections between the neighboring sheaths.”

The resulting tension allows the sheaths to vibrate together. That has a significant impact on the instrument’s sound, taking on a “twangier” quality when dry and a more of metallic gong sound when it is wet. Parikesit has tried making bundengans with other materials: paper, leaves, even plastics. But none of those produce the same sound quality as the bamboo sheaths. He next plans to investigate other musical instruments made from bamboo sheaths.“As an Indonesian, I have extra motivation because the bundengan is a piece of our cultural heritage,” Parikesit said. “I am trying my best to support the conservation and documentation of the bundengan and other Indonesian endangered instruments.”

Coupling with the human vocal tract

Meanwhile, John Smith of the University of New South Wales is equally intrigued by the physics and acoustics of the didgeridoo. The instrument is constructed from the trunk or large branches of the eucalyptus tree. The trick is to find a live tree with lots of termite activity, such that the trunk has been hollowed out leaving just the living sapwood shell. A suitably hollow trunk is then cut down, cleaned out, the bark removed, the ends trimmed, and the exterior shaped into a long cylinder or cone to produce the final instrument. The longer the instrument, the lower the pitch or key.

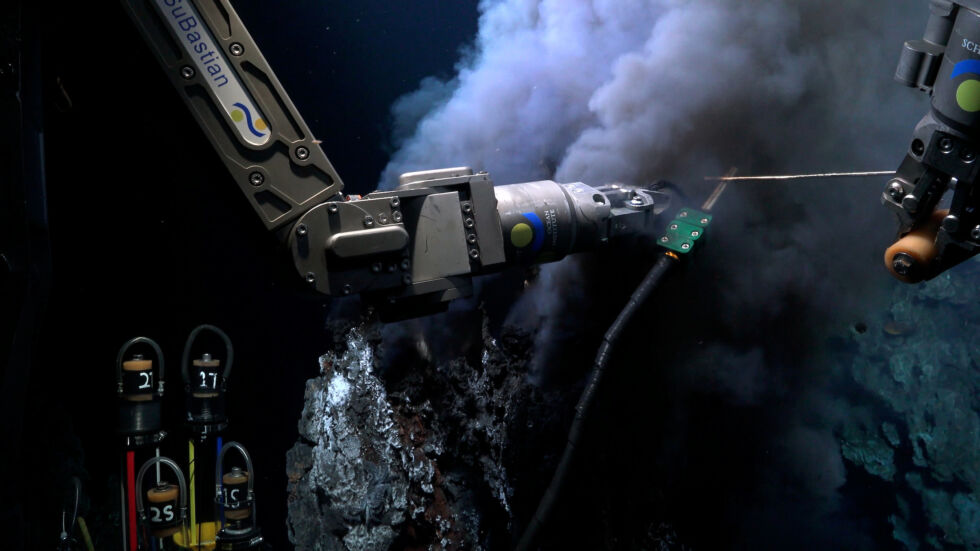

Players will vibrate their lips to play the didgeridoo in a manner similar to lip valve instruments like trumpets or trombones, except those use a small mouthpiece attached to the instrument as an interface. (Sometimes a beeswax rim is added to a didgeridoo mouthpiece end.) Players typically use circular breathing to maintain that continuous low-pitched drone for several minutes, basically inhaling through the nose and using air stored in the puffed cheeks to keep producing the sound. It’s the coupling of the instrument with the human vocal tract that makes the physics so complex, per Smith.

Smith was interested in investigating how changes in the configuration of the vocal tract produced timbral changes in the rhythmic pattern of the sounds produced. To do so, “We needed to develop a technique that could measure the acoustic properties of the player’s vocal tract while playing,” Smith said during the same press briefing. “This involved injecting a broadband signal into the corner of the player’s mouth and using a microphone to record the response.” That enabled Smith and his cohorts to record the vocal tract impedance in different configurations in the mouth.

Enlarge / Producing complex sounds with the didjeridu requires creating and manipulating resonances inside the vocal tract.

Kate Callas

The results: “We showed that strong resonances in the vocal tract can suppress bands of frequencies in the output sound,” said Smith. “The remaining strong bands of frequencies, called formants, are noticed by our hearing because they fall in the same ranges as the formants we use in speech. It’s a bit like a sculptor removing marble, and we observe the bits that are left behind.”

Smith et al. also noted that the variations in timbre arise from the player singing while playing, or imitating animal sounds (such as the dingo or the kookaburra), which produces many new frequencies in the output sound. To measure the contact between vocal folds, they placed electrodes on either side of a player’s throat and zapped them with a small high frequency electric current. They simultaneously measured lip movement with another pair of electrics above and below the lips. Both types of vibrations affect the flow of air to produce the new frequencies.

As for what makes a desirable didgeridoo that appeals to players, acoustic measurements on a set of 38 such instruments—with the quality of each rated by seven experts in seven different subjective categories—produced a rather surprising result. One might think players would prefer instruments with very strong resonances but the opposite turned out to be true. Instruments with stronger resonances were ranked the worst, while those with weaker resonances rated more highly. Smith, for one, thinks this makes sense. “This means that their own vocal tract resonance can dominate the timbre of the notes,” he said.

These scientists explored the good vibrations of the bundengan and didgeridoo Read More »