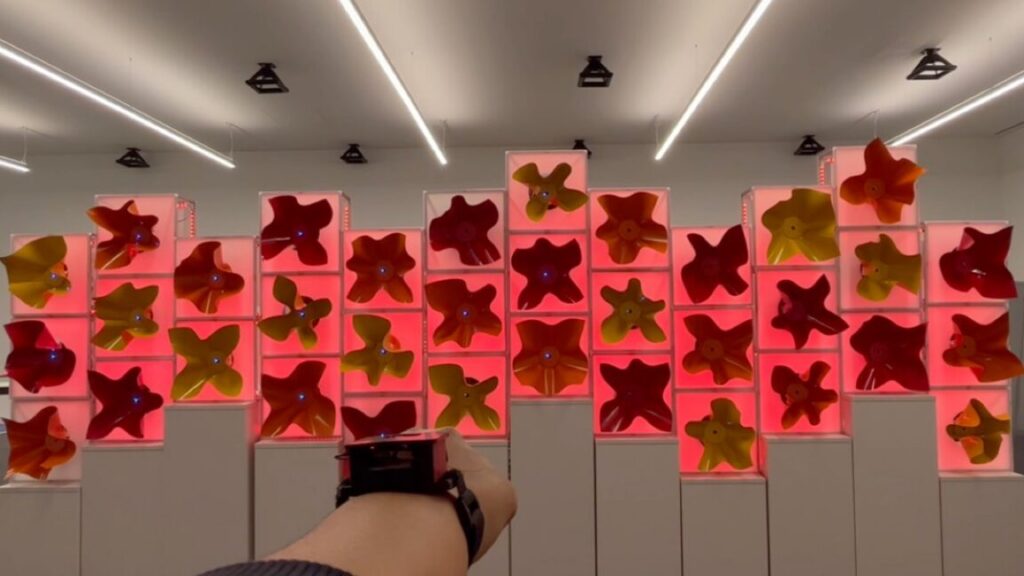

Watch a robot swarm “bloom” like a garden

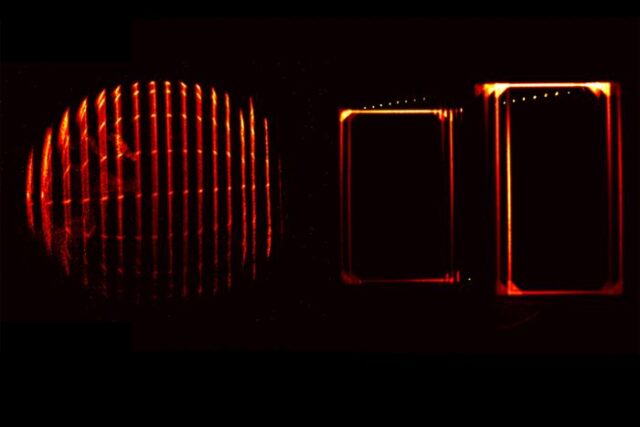

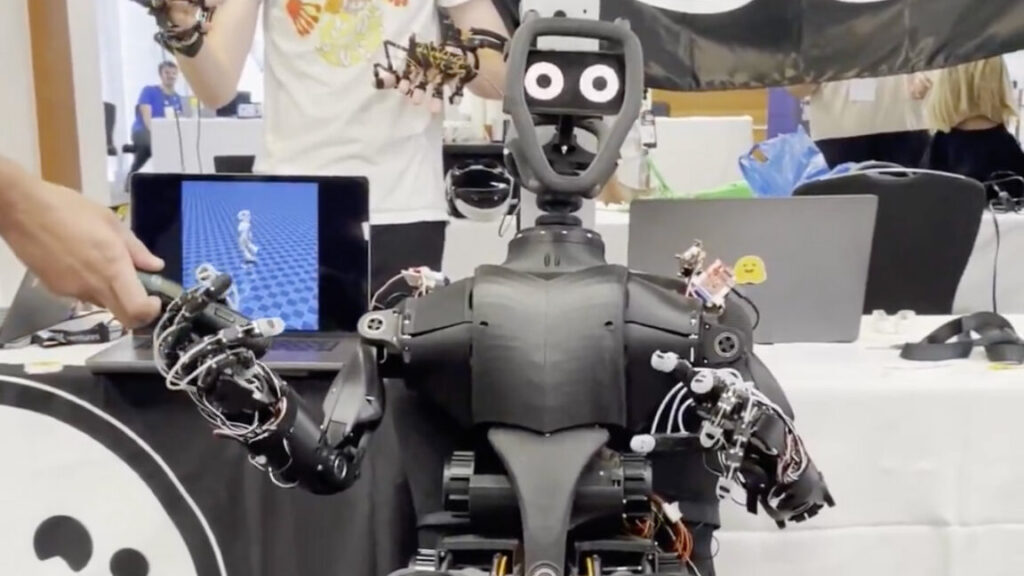

Researchers at Princeton University have built a swarm of interconnected mini-robots that “bloom” like flowers in response to changing light levels in an office. According to their new paper published in the journal Science Robotics, such robotic swarms could one day be used as dynamic facades in architectural designs, enabling buildings to adapt to changing climate conditions as well as interact with humans in creative ways.

The authors drew inspiration from so-called “living architectures,” such as beehives. Fire ants provide a textbook example of this kind of collective behavior. A few ants spaced well apart behave like individual ants. But pack enough of them closely together, and they behave more like a single unit, exhibiting both solid and liquid properties. You can pour them from a teapot like ants, as Goldman’s lab demonstrated several years ago, or they can link together to build towers or floating rafts—a handy survival skill when, say, a hurricane floods Houston. They also excel at regulating their own traffic flow. You almost never see an ant traffic jam.

Naturally scientists are keen to mimic such systems. For instance, in 2018, Georgia Tech researchers built ant-like robots and programmed them to dig through 3D-printed magnetic plastic balls designed to simulate moist soil. Robot swarms capable of efficiently digging underground without jamming would be super beneficial for mining or disaster recovery efforts, where using human beings might not be feasible.

In 2019, scientists found that flocks of wild jackdaws will change their flying patterns depending on whether they are returning to roost or banding together to drive away predators. That work could one day lead to the development of autonomous robotic swarms capable of changing their interaction rules to perform different tasks in response to environmental cues.

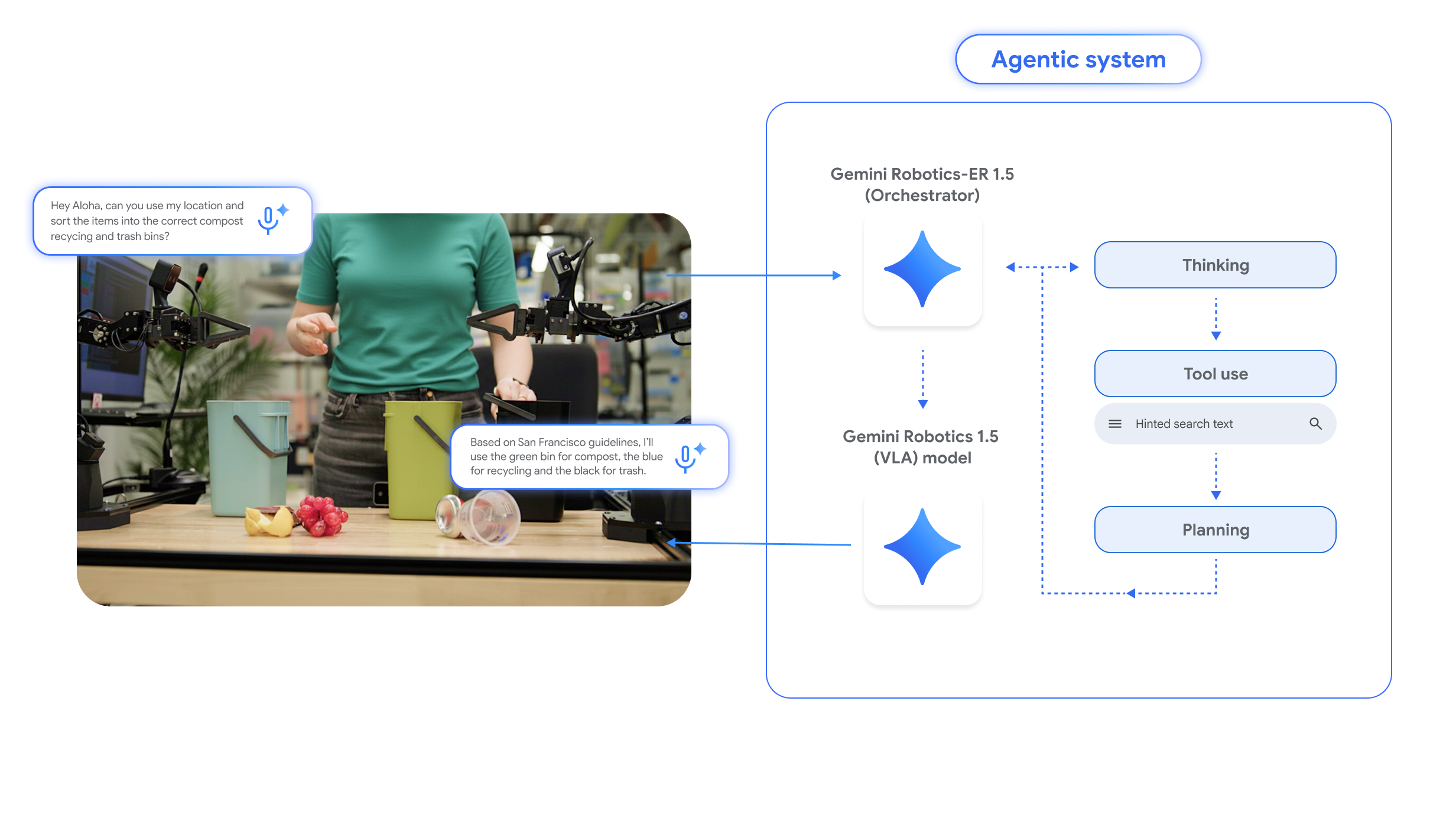

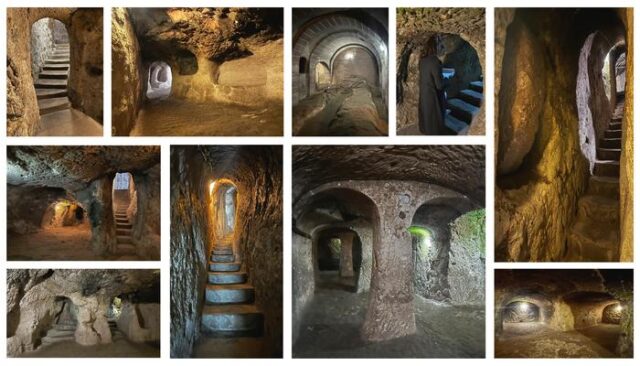

The authors of this latest paper note that plants can optimize their shape to get enough sunlight or nutrients, thanks to individual cells that interact with each other via mechanical and other forms of signaling. By contrast, the architecture designed by human beings is largely static, composed of rigid fixed elements that hinder building occupants’ ability to adapt to daily, seasonal, or annual variations in climate conditions. There have only been a few examples of applying swarm intelligence algorithms inspired by plants, insects, and flocking birds to the design process to achieve more creative structural designs, or better energy optimization.

Watch a robot swarm “bloom” like a garden Read More »