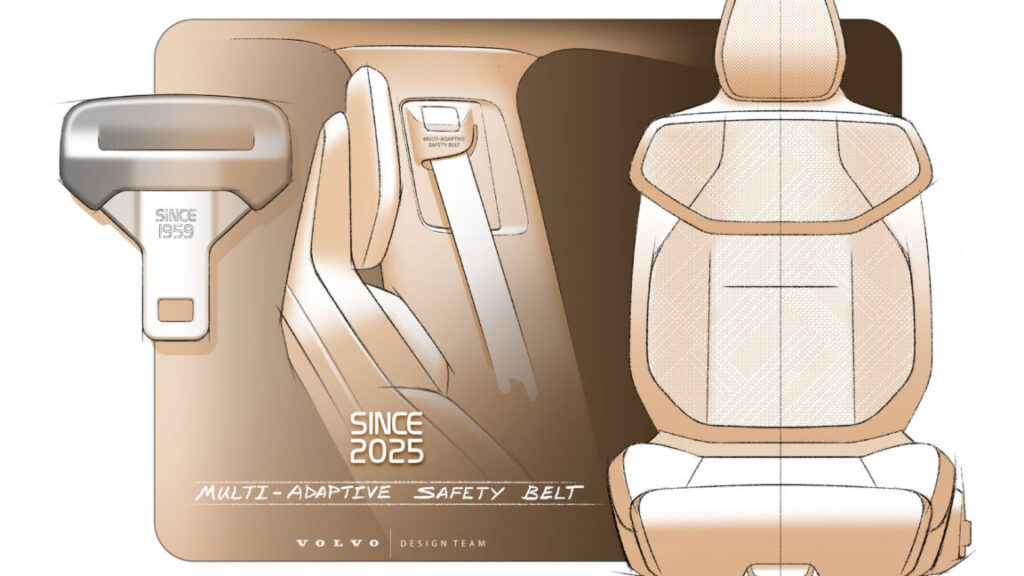

Volvo invented the three-point seat belt 67 years ago; now it has improved it

No other automaker has the same commitment to road safety as Volvo. Credit: Volvo Cars

How it works

Basically, a seat belt is made up of a retractor mechanism, buckle assembly, webbing material, and a pretensioner device. Of these parts, the pretensioner is the one tasked with tightening the seatbelt webbing in a collision. As such, it reduces the forward movement of the passenger before the airbag deploys at speeds of up to 200 mph (321 km/h). All of these parts remain the same for Volvo’s newest seat belt iteration. It’s the tiny brain attached to the assemblage that’s different.

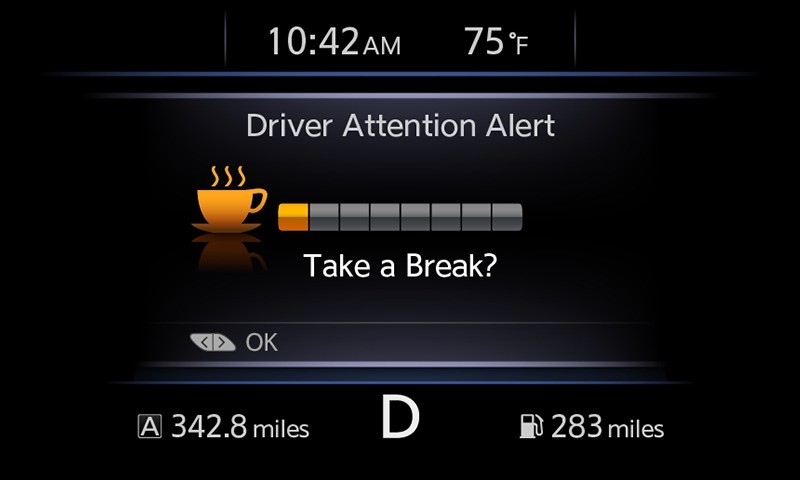

Volvo’s new central computing system, HuginCore (named after a bird in Norse mythology), runs the EX60 with more than 250 trillion operations per second. It has been developed in-house, together with its partners Google, Nvidia, and Qualcomm.

“With the HuginCore system we can collect a lot of data and make decisions in the car instantly and combine that with the belt’s ability to choose different load levels,” says Åsa Haglund, head of the Volvo Cars Safety Center. “A box of possibilities opens up where you can detect what type of crash it is and who is in the car and choose a more optimal belt force.”

Every day, dummies like these get smashed to make Volvos safer. Credit: Volvo Cars

Load limiters control how much force the safety belt applies to the human body during a crash. Volvo’s new system pushes the load-limiting profiles from three to 11, marking a major increase in adjustability. It’s kind of like an audio system, Ljung Aust muses. A sound system with 10 discrete steps up the volume ladder offers varied profiles along the way, while one with only one or two steps addresses fewer preference levels.

Using data from exterior, interior, and crash sensors, the car reacts to a collision in milliseconds—less than the blink of an eye, Ljung Aust says. In the case of a crash, it’s critical to hold the hips into the car, he explains, but the upper body should fold forward in a frontal crash in a nice, smooth motion to meet the airbag. Otherwise, the body is exposed to the same force as the slowing car.

Volvo invented the three-point seat belt 67 years ago; now it has improved it Read More »