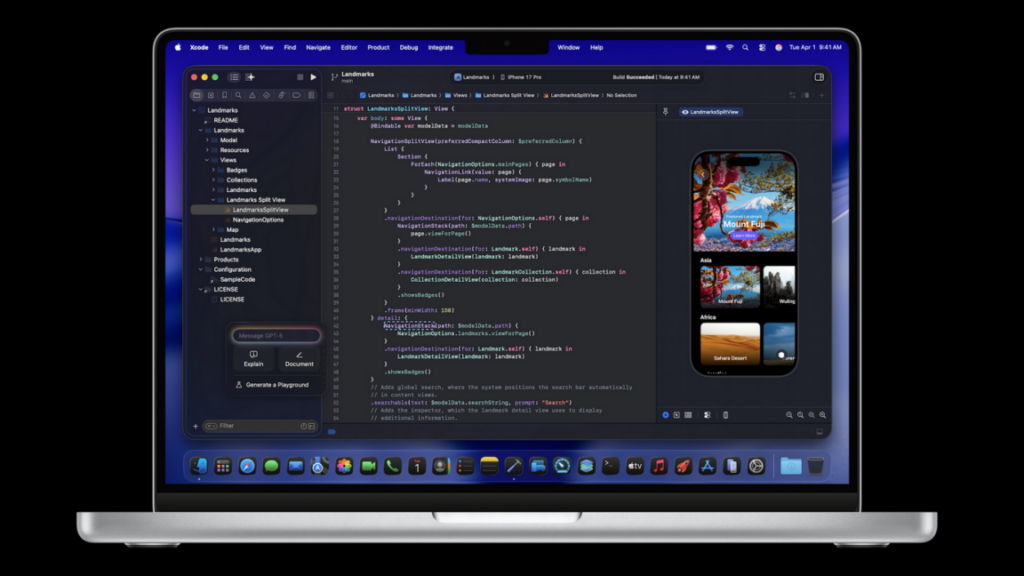

Xcode 26.3 adds support for Claude, Codex, and other agentic tools via MCP

Apple has announced a new version of Xcode, the latest version of its integrated development environment (IDE) for building software for its own platforms, like the iPhone and Mac. The key feature of 26.3 is support for full-fledged agentic coding tools, like OpenAI’s Codex or Claude Agent, with a side panel interface for assigning tasks to agents with prompts and tracking their progress and changes.

This is achieved via Model Context Protocol (MCP), an open protocol that lets AI agents work with external tools and structured resources. Xcode acts as an MCP endpoint that exposes a bunch of machine-invocable interfaces and gives AI tools like Codex or Claude Agent access to a wide range of IDE primitives like file graph, docs search, project settings, and so on. While AI chat and workflows were supported in Xcode before, this release gives them much deeper access to the features and capabilities of Xcode.

This approach is notable because it means that even though OpenAI and Anthropic’s model integrations are privileged with a dedicated spot in Xcode’s settings, it’s possible to connect other tooling that supports MCP, which also allows doing some of this with models running locally.

Apple began its big AI features push with the release of Xcode 26, expanding on code completion using a local model trained by Apple that was introduced in the previous major release, and fully supporting a chat interface for talking with OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Anthropic’s Claude. Users who wanted more agent-like behavior and capabilities had to use third-party tools, which sometimes had limitations due to a lack of deep IDE access.

Xcode 26.3’s release candidate (the final beta, essentially) rolls out imminently, with the final release coming a little further down the line.

Xcode 26.3 adds support for Claude, Codex, and other agentic tools via MCP Read More »