Switch 2 is around the corner, but Nintendo announces a new Switch accessory anyway

better late than never? —

Oddly timed accessory is released as the Switch’s life cycle is winding down.

-

Nintendo’s Joy-Con Charging Stand (Two-Way) seems useful, but it’s coming out at a strange time in the console’s lifecycle.

Nintendo

-

The stand can charge the Switch Online NES controllers, something that Nintendo’s charging grip can’t do because the handles get in the way.

Nintendo

-

The charging stand can be removed from the stand part to maximize flexibility.

Nintendo

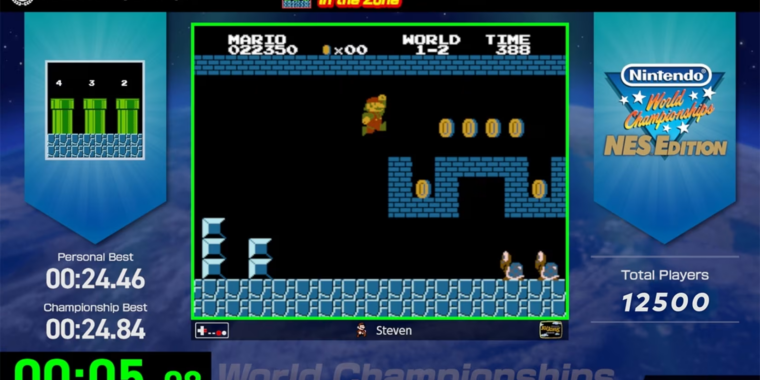

Nintendo’s Switch launched in March 2017, and all available information indicates that the company is on track to announce a successor early next year. It’s that timing that makes the launch of Nintendo’s latest Switch accessory so odd: The company has announced a first-party charging cradle for Joy-Con controllers, which up until now have been charged by slotting them into the console itself, via Nintendo’s sold-separately Joy-Con charging grip, or with third-party charging accessories.

The Nintendo of Europe account on X, formerly Twitter, announced that the charging accessory—formally called the “Joy-Con Charging Stand (Two-Way)”—will be released on October 17. It will work with both Joy-Cons and the Switch Online wireless NES controllers, and the charging cradle can be separated from its stand (where it looks a lot like the Joy-Con charging grip but without the grip part).

Power is provided via a USB-C port on top of the stand, which can either be connected to one of the Switch dock’s USB ports or to a separate USB-C charger. Other Switch controllers, including the Pro Controller and the SNES and N64 replica controllers, are charged via USB-C directly.

The Verge reports that the accessory has only been announced for Europe and Japan so far, though it will presumably also come to North America at some point. Pricing hasn’t been announced yet, either.

Switch 2 is around the corner

Why would Nintendo release a new first-party charging accessory for your old console just months before it’s slated to announce its next-generation console? Rumors about the design of the Switch 2 could hold some hints.

Accessory makers and others with firsthand knowledge of the Switch 2 have suggested that the new console will come with redesigned Joy-Cons with additional buttons and a magnetic attachment mechanism. This would likely make it impossible to attach current-generation Joy-Cons, which physically interlock with the Switch and its various accessories.

But reporting also suggests that the Switch 2 will retain backward compatibility with digital and physical Switch games, which could justify retaining some kind of backward compatibility with existing controllers. This new Joy-Con charging cradle could provide current Switch owners a way to continue charging Joy-Cons and NES controllers even if they can no longer be attached to and charged by the console itself.

But that’s just speculation at this point. It could just as easily be the case that Nintendo has to keep the Switch going for one more holiday season, and it’s eager to sell every accessory it can alongside the shrinking but still significant number of consoles it will sell between now and the time the Switch 2 is released. Nintendo recently announced new games in the Legend of Zelda and Mario & Luigi series, which will give past and future Switch buyers a reason to keep their Joy-Cons charged in the first place.

Nintendo has taken pains to make old controllers compatible with new consoles before. Most Nintendo Wii consoles came with built-in GameCube controller ports, which enabled backward compatibility with GameCube games and also allowed GameCube controllers to be used with compatible Wii games like Super Smash Bros. Brawl. Wii remotes also continued to function with the Wii U.

One thing we don’t know about the Switch 2’s backward compatibility is whether it will provide any kind of graphical enhancements for Switch games. Several titles released in recent years, including newer Pokémon titles, have suffered from performance issues. Nintendo had reportedly planned to release a more powerful “Switch Pro” at some point in 2021 or 2022, but the update was apparently scrapped in favor of the more modestly updated OLED Switch.

Listing image by Nintendo

Switch 2 is around the corner, but Nintendo announces a new Switch accessory anyway Read More »