Man’s ghastly festering ulcer stumps doctors—until they cut out a wedge of flesh

The man made a full recovery, but this tale is not for the faint of heart.

If you were looking for some motivation to follow your doctor’s advice or remember to take your medicine, look no further than this grisly tale.

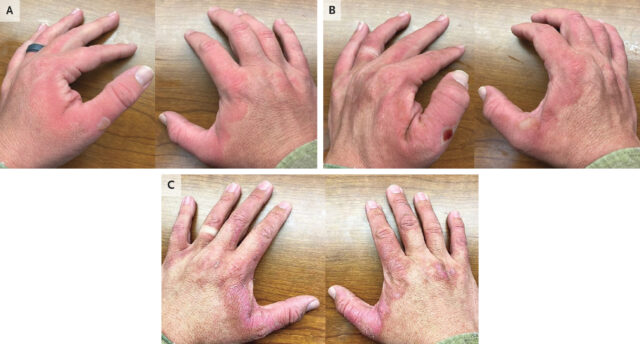

A 64-year-old man went to the emergency department of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston with a painful festering ulcer spreading on his left, very swollen ankle. It was a gruesome sight; the open sore was about 8 by 5 centimeters (about 3 by 2 inches) and was rimmed by black, ashen, and dark purple tissue. Inside, it oozed with streaks and fringes of yellow pus around pink and red inflamed flesh. It was 2 cm deep (nearly an inch). And it smelled.

The man told doctors it had all started two years prior, when dark, itchy lesions appeared in the area on his ankle—the doctors noted that there were multiple patches of these lesions on both his legs. But about five months before his visit to the emergency department, one of the lesions on his left ankle had progressed to an ulcer. It was circular, red, tender, and deep. He sought treatment and was prescribed antibiotics, which he took. But they didn’t help.

You can view pictures of the ulcer and its progression here, but be warned, it is graphic. (Panel A shows the ulcer five months prior to the emergency department visit. Panel B shows the ulcer one month prior. Panel C shows the wound on the day of presentation at the emergency department. Panel D shows the area three months after hospital discharge.)

Gory riddle

The ulcer grew. In fact, it seemed as though his leg was caving in as the flesh around it began rotting away. A month before the emergency room visit, the ulcer was a gaping wound that was already turning gray and black at the edges. It was now well into the category of being a chronic ulcer.

In a Clinical Problem-Solving article published in the New England Journal of Medicine this week, doctors laid out what they did and thought as they worked to figure out what was causing the man’s horrid sore.

With the realm of possibilities large, they started with the man’s medical history. The man had immigrated to the US from Korea 20 years ago. He owned and worked at a laundromat, which involved standing for more than eight hours a day. He had a history of eczema on his legs, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and Type 2 diabetes. For these, he was prescribed a statin for his cholesterol, two blood pressure medications (hydrochlorothiazide and losartan), and metformin for his diabetes. He told doctors he was not good at taking the regimen of medicine.

His diabetes was considered “poorly controlled.” A month prior, he had a glycated hemoglobin (A1C or HbA1C) test—which indicates a person’s average blood sugar level over the past two or three months. His result was 11 percent, while the normal range is between 4.2 and 5.6 percent.

His blood pressure, meanwhile, was 215/100 mm Hg at the emergency department. For reference, readings higher than 130/80 mm Hg on either number are considered the first stage of high blood pressure. Over the past three years, the man’s blood pressure had systolic readings (top number, pressure as heart beats) ranging from 160 to 230 mm Hg and diastolic readings (bottom number, pressure as heart relaxes) ranging from 95 to 120 mm Hg.

Clinical clues

Given the patient’s poorly controlled diabetes, a diabetic ulcer was initially suspected. But the patient didn’t have any typical signs of diabetic neuropathy that are linked to ulcers. These would include numbness, unusual sensations, or weakness. His responses on a sensory exam were all normal. Diabetic ulcers also typically form on the foot, not the lower leg.

X-rays of the ankle showed swelling in the soft tissue but without some signs of infection. The doctors wondered if the man had osteomyelitis, an infection in the bone, which can be a complication in people with diabetic ulcers. The large size and duration of the ulcer matched with a bone infection, as well as some elevated inflammatory markers he had on his blood tests.

To investigate the bone infection further, they admitted the man to the hospital and ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But the MRI showed only a soft-tissue defect and a normal bone, ruling out a bone infection. Another MRI was done with a contrast agent. That showed that the man’s large arteries were normal and there were no large blood clots deep in his veins—which is sometimes linked to prolonged standing, as the man did at his laundromat job.

As the doctors were still working to root out the cause, they had started him on a heavy-duty regimen of antibiotics. This was done with the assumption that on top of whatever caused the ulcer, there was now also a potentially aggressive secondary infection—one not knocked out by the previous round of antibiotics the man had been given.

With a bunch of diagnostic dead ends piling up, the doctors broadened their view of possibilities, newly considering cancers, rare inflammatory conditions, and less common conditions affecting small blood vessels (as the MRI has shown the larger vessels were normal). This led them to the possibility of a Martorell’s ulcer.

These ulcers, first described in 1945 by a Spanish doctor named Fernando Martorell, form when prolonged, uncontrolled high blood pressure causes the teeny arteries below the skin to stiffen and narrow, which blocks the blood supply, leading to tissue death and then ulcers. The ulcers in these cases tend to start as red blisters and evolve to frank ulcers. They are excruciatingly painful. And they tend to form on the lower legs, often over the Achilles’ tendon, though it’s unclear why this location is common.

What the doctor ordered

The doctors performed a punch biopsy of the man’s ulcer, but it was inconclusive—which is common with Martorell’s ulcers. The doctors turned to a “deep wedge biopsy” instead, which is exactly what it sounds like.

A pathology exam of the tissue slices from the wedge biopsy showed blood vessels that had thickened and narrowed. It also revealed extensive inflammation and necrosis. With the pathology results as well as the clinical presentation, the doctors diagnosed the man with a Martorell’s ulcer.

They also got back culture results from deep-tissue testing, finding that the man’s ulcer had also become infected with two common and opportunistic bacteria—Serratia marcescens and Enterococcus faecalis. Luckily, these are generally easy to treat, so the doctors scaled back his antibiotic regimen to target just those germs.

The man underwent three surgical procedures to clean out the dead tissue from the ulcer, then a skin graft to repair the damage. Ultimately, he made a full recovery. The doctors at first set him on an aggressive regimen to control his blood pressure, one that used four drugs instead of the two he was supposed to be taking. But the four-drug regimen caused his blood pressure to drop too low, and he was ultimately moved back to his original two-drug treatment.

The finding suggests that if he had just taken his original medications as prescribed, he would have kept his blood pressure in check and avoided the ulcer altogether.

In the end, “the good outcome in this patient with a Martorell’s ulcer underscores the importance of blood-pressure control in the management of this condition,” the doctors concluded.

Beth is Ars Technica’s Senior Health Reporter. Beth has a Ph.D. in microbiology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and attended the Science Communication program at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She specializes in covering infectious diseases, public health, and microbes.

Man’s ghastly festering ulcer stumps doctors—until they cut out a wedge of flesh Read More »