Questions swirl after Trump’s GLP-1 pricing deal announcement

While some may stand to gain access to the drugs under these categories, another factor in assessing the deal’s impact is that millions are expected to lose federal health coverage under the Trump administration’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.”

Unmatched prices

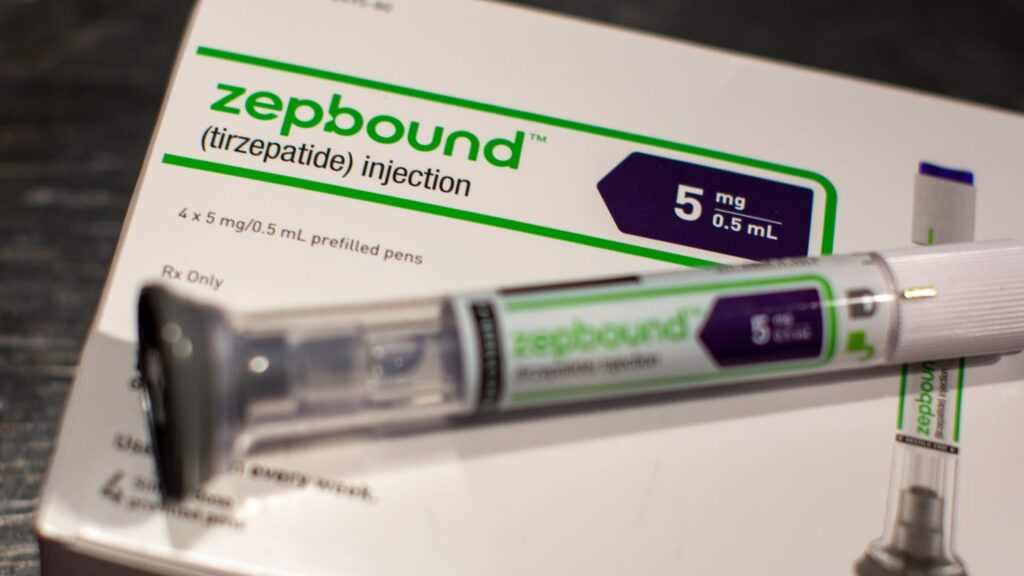

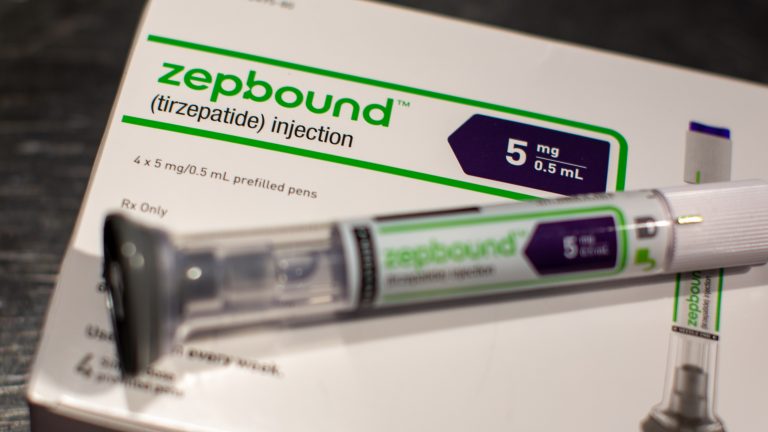

In addition to the deals for federal programs, the administration also announced new direct-to-consumer prices. Currently, people with a prescription can buy the most popular drugs, Wegovy and Zepbound, directly from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, respectively, for $499 each. Under the new deal, Wegovy will be available for $350, as will Ozempic. And Zepbound will be available at “an average” of $346. While the prices are lower, the out-of-pocket costs are still likely to be more than most people would pay if they went through an insurance plan, and paying outside their insurance policies means that the payments won’t be counted toward out-of-pocket maximums and other tallies. Generally, experts expect that direct-to-consumer sales won’t play a significant role in lowering overall drug costs.

It remains unclear if Trump’s deal will have any effect on GLP-1 prices for those on commercial insurance plans.

Trump hailed the deals, calling them “most favored-nation pricing.” But even with the lower prices for some, Americans are still paying more than foreign counterparts. As Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) noted last year, while Novo Nordisk set Ozempic’s list price at nearly $1,000 in the US and the new deal is as low as $245, the drug costs just $155 in Canada, $122 in Italy, $71 in France, and $59 in Germany. Wegovy, similarly, is $186 in Denmark, $137 in Germany, and $92 in the United Kingdom. Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro is $94 in Japan.

A study published last year in JAMA Network Open led by researchers at Yale University estimated that the manufacturing cost for this class of drugs is under $5 for a month’s supply.

The announcement also said that future GLP-1 drugs in pill form (rather than injections) from the two companies will be priced at $150. That price will be for federal programs and direct-to-consumer sales. While such pills are nearing the market, none are currently available or approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Given that they are not yet for sale, the cost savings from this deal are unknown.

Questions swirl after Trump’s GLP-1 pricing deal announcement Read More »