Archaeologists find a supersized medieval shipwreck in Denmark

the wreck and the story of the wreck

The sunken ship reveals that the medieval European economy was growing fast.

This is a replica of another cog, based on an excavated shipwreck from Bremen. Note the sterncastle. Credit: VollwertBIT

This is a replica of another cog, based on an excavated shipwreck from Bremen. Note the sterncastle. Credit: VollwertBIT

Archaeologists recently found the wreck of an enormous medieval cargo ship lying on the seafloor off the Danish coast, and it reveals new details of medieval trade and life at sea.

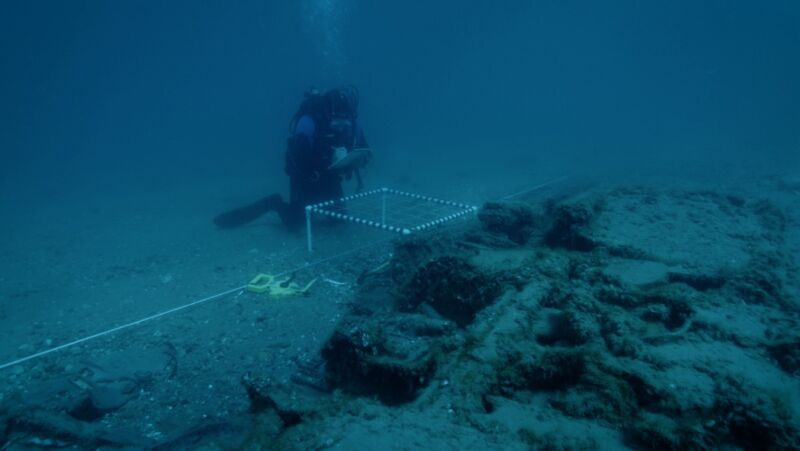

Archaeologists discovered the shipwreck while surveying the seabed in preparation for a construction project for the city of Copenhagen, Denmark. It lay on its side, half-buried in the sand, 12 meters below the choppy surface of the Øresund, the straight that runs between Denmark and Sweden. By comparing the tree rings in the wreck’s wooden planks and timbers with rings from other, precisely dated tree samples, the archaeologists concluded that the ship had been built around 1410 CE.

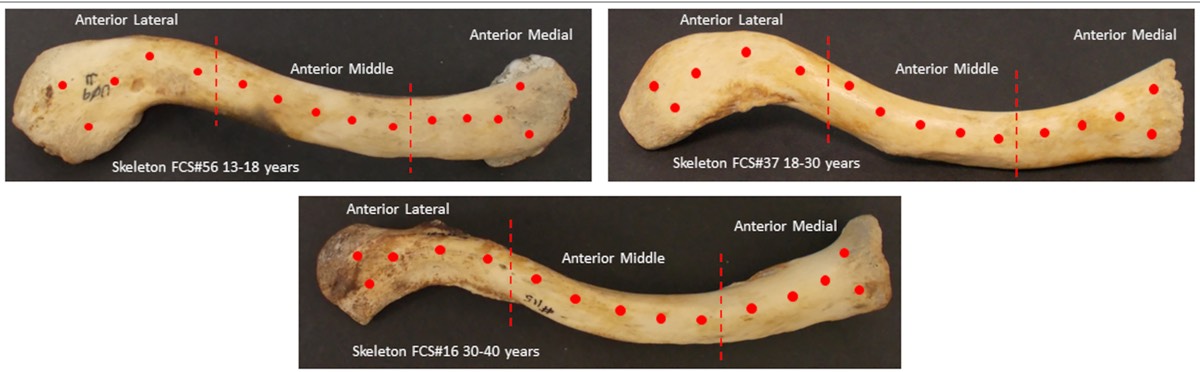

The Skaelget 2 shipwreck, with a diver for scale. Credit: Viking Ship Museum

A medieval megaship

Svaelget 2, as archaeologists dubbed the wreck (its original name is long since lost to history), was a type of merchant ship called a cog: a wide, flat-bottomed, high-sided ship with an open cargo hold and a square sail on a single mast. A bigger, heavier, more advanced version of the Viking knarrs of centuries past, the cog was the high-tech supertanker of its day. It was built to carry bulky commodities from ports in the Netherlands, north around the coast of Denmark, and then south through the Øresund to trading ports on the Baltic Sea—but this one didn’t quite make it.

Most cogs would have been about 15 to 25 meters long and 5 to 8 meters wide, capable of carrying about 200 tons of cargo—big, impressive ships for their time. But Svaelget 2, an absolute unit of a ship, measured about 28 meters from bow to stern, 9 meters wide, and could have carried about 300 tons. Its size alone was a surprise to the archaeologists.

“We now know, undeniably, that cogs could be this large—that the ship type could be pushed to this extreme,” said archaeologist Otto Uldum of Denmark’s Viking Ship Museum, who led the excavation, in a press release.

Medieval Europe’s merchant class was growing in both size and wealth in the early 1400s, and the cog was both a product of that growth and the engine driving it. The mere fact of its existence points to a society that could afford to invest in building big, expensive trading ships (and could confidently expect a return on that investment). And physically, it’s a product of the same trading networks it supplied: while the heavy timbers of its frame were cut locally in the Netherlands, the Pomeranian oak planks of Svaelget 2’s hull came from Poland.

“The cog revolutionized trade in northern Europe,” said Uldum. “It made it possible to transport goods on a scale never seen before.”

The super ship’s superb superstructure

For about 600 years, layers of sand had protected the starboard (right, for you landlubbers) side of the wreck from erosion and decay. Nautical archaeologists usually find only the very bottoms of cogs; the upper structures of the ship—rigging, decks, and castles—quickly decay in the ocean. That means that some of the most innovative parts of the ships’ construction appear only in medieval drawings and descriptions.

But Svaelget 2 offers archaeologists a hands-on look at the real deal, from rigging to the ship’s galley and the stern castle: a tall wooden structure at the back of the ship, where crew and passengers could have sought at least a little shelter from the elements. Medieval drawings and texts describe cogs having high castles at both bow and stern, but archaeologists have never gotten to examine a real one to learn how it’s put together or how it connects with the rest of the ship’s construction.

“We have plenty of drawings of castles, but they have never been found because usually only the bottom of the ship survives,” said Uldum. “[The castle] is a big step forward compared to Viking Age ships, which had only open decks in all kinds of weather.”

Lying on and around the remains of the cog’s decks, Uldum and his colleagues also found stays (ropes that would have held the mast in place) and lines for controlling the ship’s single square sail, along with ropes and chains that would once have secured the merchant vessel’s cargo in the open hold.

Life at sea in the Middle Ages

The cog would probably have sailed with between 30 and 45 crew members. No remains were found on the wreck, but the lost crew left behind small, tantalizing traces of their lives and their presence. Uldum and his colleagues found combs, shoes, and rosary beads, along with dishes and tableware.

“The sailor brought his comb to keep his hair neat and his rosary to say his prayers,” said Uldum (and one has to picture the sailor’s grandmother beaming proudly at that description). “These personal objects show us that the crew brought everyday items with them. They transferred their life on land to life at sea.”

Life at sea, for the medieval sailors aboard Svaelget 2, would have included at least occasional hot meals, cooked in bronze pots over an open fire in the ship’s galley and eaten on dishes of ceramic and painted wood. Bricks (about 200 of them) and tiles formed a sort of fireplace where the cook could safely build a fire aboard the otherwise very flammable ship.

“It speaks of remarkable comfort and organization on board,” said Uldum. “Now sailors could have hot meals similar to those on land, instead of the dried and cold food that previously dominated life at sea.” Plenty of dried meat and cold biscuits still awaited sailors for the next several centuries, of course, but when weather and time permitted, at least the crew of Svaelget 2 could gather around a hot meal. The galley would have been a relatively new part of shipboard life for sailors in the early 1400s—and it quickly became a vital one.

Cargo? Go where?

One thing usually marks the site of a shipwreck, even when everything else has disintegrated into the ocean: ballast stones. When merchant ships were empty, they carried stones in their holds to help keep the ship stable; otherwise, the empty ship would be top-heavy and prone to tipping over, which is usually not ideal. (Modern merchant vessels use water, in special tanks, for ballast.) But Uldum and his colleagues didn’t find ballast stones on Svaelget 2, which means the cog was probably fully laden with cargo when it sank.

But the cargo is also conspicuously absent. Cogs were built to carry bulk goods—things like bricks, grain and other staple foods, fabric, salt, and timber. Those goods would have been stowed in an open hold amidships, secured by ropes and chains (some of which remain on the wreck). But barrels, boards, and bolts of fabric all float. As the ship sank and water washed into the hold, it would have carried away the cargo.

Some of it may have washed up on the shores or even more distant beaches, becoming a windfall for local residents. The rest probably sank to the bottom of the sea, far from the ship and its destination.

Archaeologists find a supersized medieval shipwreck in Denmark Read More »