Intel shores up its desktop CPU lineup with boosted Core Ultra 200S Plus chips

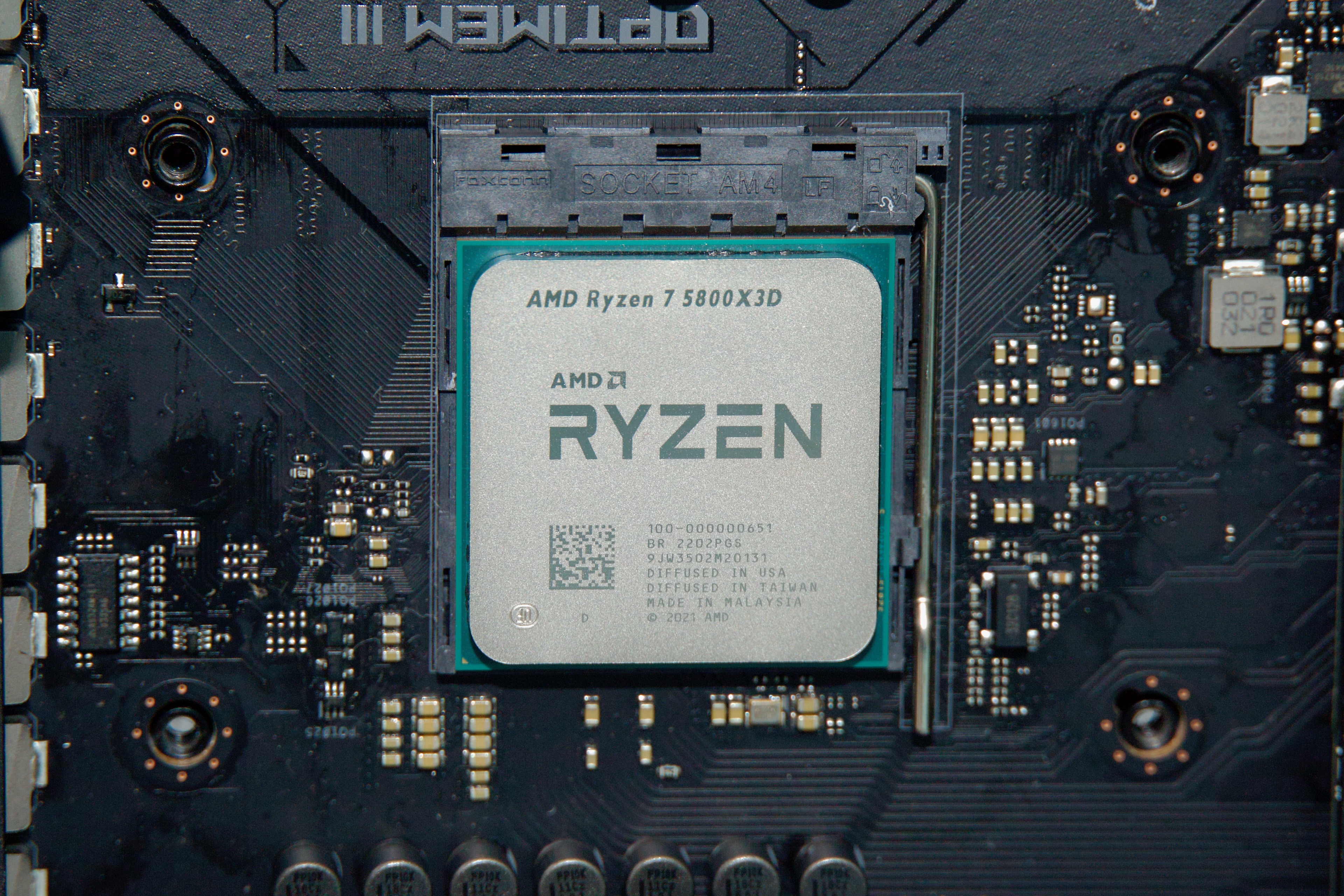

Intel’s Core Ultra 200S desktop chips, codenamed “Arrow Lake,” first launched in late 2024, and they were the most significant updates to Intel’s desktop CPU lineup in years. But that didn’t mean they were always improvements over what came before: while they’re power-efficient and run cooler than older 13th- and 14th-generation Core CPUs, they sometimes struggled to match those older chips’ gaming performance. And for gaming systems in particular, they’ve always had to live in the shadow of AMD’s Ryzen 7000 and 9000-series X3D processors, chips with extra L3 cache that disproportionately benefits games.

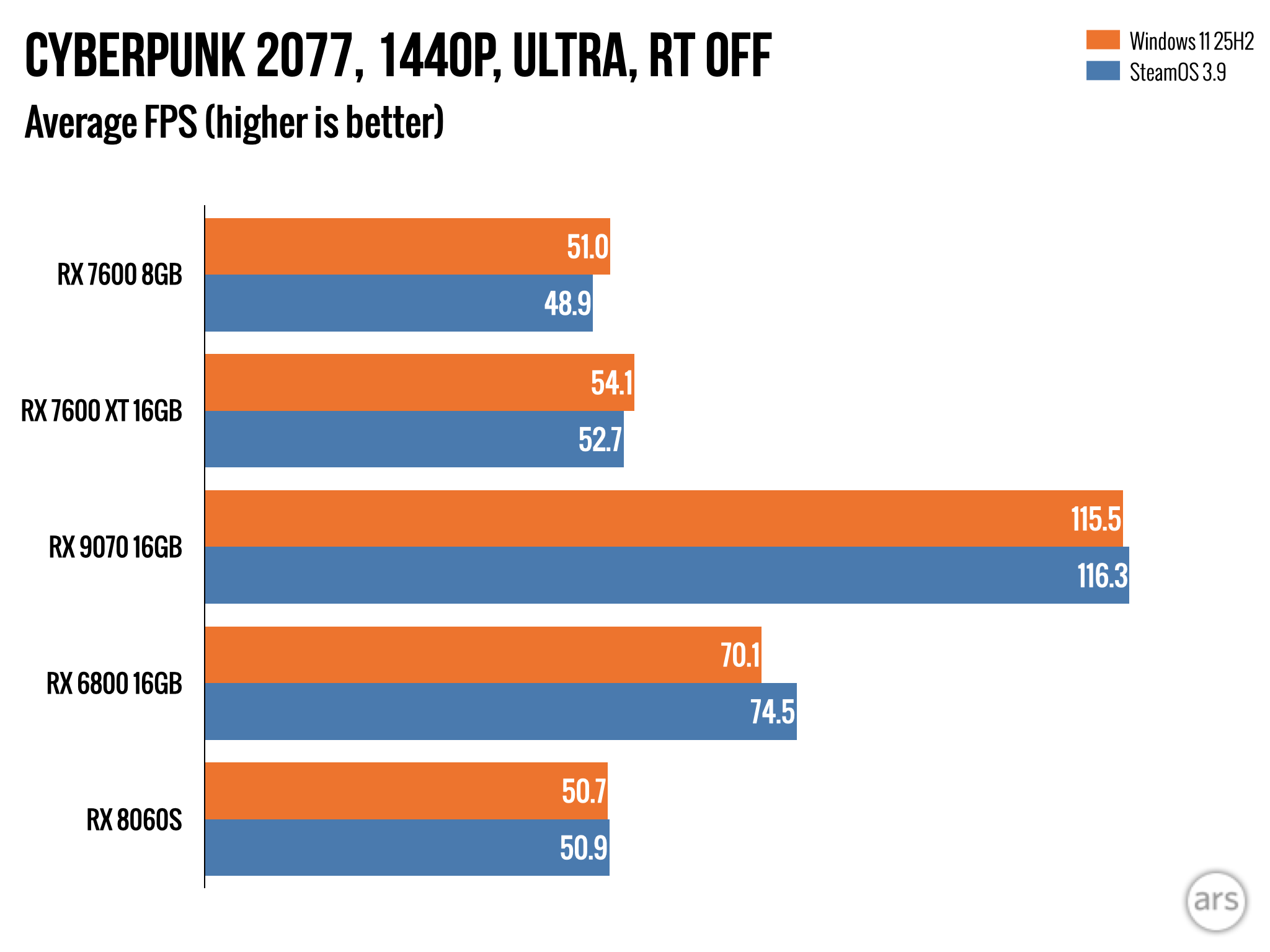

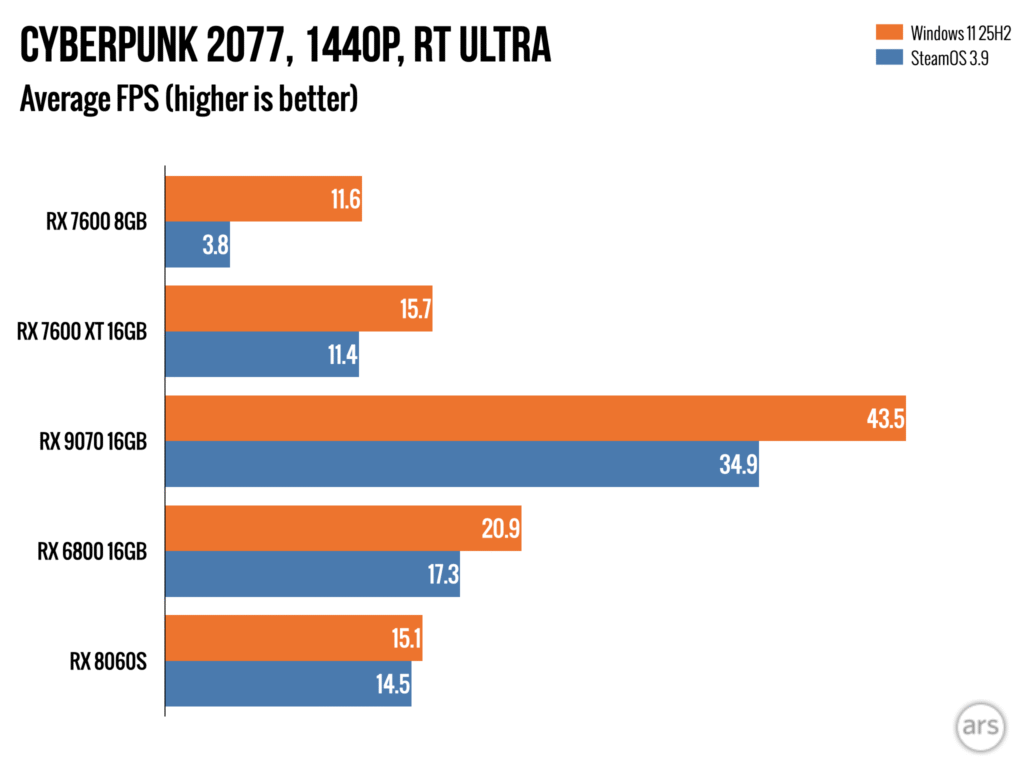

Intel doesn’t have a next-generation upgrade available for desktops yet, but it is shoring up its desktop lineup with a pair of upgraded chips. The Core Ultra 200S Plus processors (also referred to as Arrow Lake Refresh, in some circles) add more processor cores, boost clock speeds, add support for faster memory, and speed up the internal communication between different parts of the processor. Collectively, Intel says these improvements will boost gaming performance by an average of 15 percent.

The Core Ultra 7 270K Plus and 270KF Plus (a real mouthful, all of these names are getting to be) add four more efficiency cores compared to the Core Ultra 7 265K, bringing the total number of cores to 24 (8 P-cores and 16 E-cores). If you wanted that many CPU cores previously, you would have had to spring for a Core Ultra 9 chip. The Core Ultra 5 250K Plus and 250KF Plus also get four more E-cores than the 245K, bringing its total to 6 P-cores and 12 E-cores.

Intel shores up its desktop CPU lineup with boosted Core Ultra 200S Plus chips Read More »