I’d split the latest housing roundup into local versus global questions. I was planning on waiting a bit between them.

Then Joe Biden decided to propose a version of the worst possible thing.

So I guess here we are.

What is the organizing principle of Bidenomics?

This was the old counterproductive Biden proposal:

Unusual Whales: Biden to propose $5,000 credit for first-time home buyers, per WaPo.

The Rich: House prices about to go up $5,000 everywhere.

Under current conditions this is almost a pure regressive tax, a transfer from those too poor to own a home to those who can afford to buy one, or who previously owned one and no longer do.

If there were no restrictions on the supply of housing, such that the price of a house equalled the cost of construction plus the underlying price of land, then the subsidy would work, but also you would not need it.

Yes, this implies that many good policy interventions are available.

Biden then literally doubled down on this proposal, which Tyler Cowen correctly labeled ‘from the era of insane economic policy’: Joe Biden proposes to pay new homeowners $9600 of taxpayer money at $400/month for two years. Why are we transferring money from existing homeowners and those who cannot afford to home to this particular middle group?

To be fair to Joe Biden here, and I initially made this mistake as well, no prices will not rise by almost $9600 per house allowing existing homeowners to capture all the loot in an accounting sense. Only about half of home buyers are first time purchasers, and by buying they are using up a valuable one-time resource. So my guess would be this only increases home values by about $5000.

Also note that if all home values go up by $5000, that does not mean that homeowners are that much wealthier unless they own more house than they need. If you live in one house and own one house, you are closer to economically flat housing than to being long one house. You have to live somewhere.

I also note that Biden’s proposal of $400/month for two years means that the first time homebuyer likely cannot use that $9600 as part of their down payment on the house. So the one actual plausible thing this might have done, to allow first time buyers to assemble their down payment, doesn’t even work. Madness.

Here is the best counterargument I have seen.

Zack Kanter: I’m amazed at the outcry in response to this. “Subsidizing demand will just drive up housing prices!” Anyone smart enough to understand the fundamental irrationality here should be smart enough to know that the goal isn’t to drive down housing prices, but rather to buy votes.

GFodor: At this point it is so ridiculously corrupt and stupid I would rather we just be transparent and set up online auctions for my vote to be bid on.

He is right, of course. I am aware that this is centrally a fully cynical bribery scheme to buy votes, with at most a minor amount of being so foolish as to think this might accomplish anything else.

But that’s not all! It can get so much worse.

Daryl Fairweather: From Biden’s just released housing plan: This “lock-in” effect makes homeowners more reluctant to sell and give up that low [mortgage] rate, even in circumstances where their current homes no longer fit their household needs.

The President is calling on Congress to provide a one-year tax credit of up to $10,000 to middle-class families who sell their starter home, defined as homes below the area median home price in the county, to another owner-occupant.

This is mostly a giveaway to banks. Families are staying in their homes because banks issued what for the banks are highly unprofitable mortgages. So we are going to bribe families to prepay horribly unprofitable mortgages.

Also note that if there is no such mortgage we are literally handing people checks exactly because they own their home, in exchange for paying the costs of moving.

Also we reduced ‘mortgage insurance premiums’ by $800, which sounds like another transfer from people without homes to people with homes, and a complete disregard for how insurance is supposed to work.

Why does Biden keep trying to write public checks to richer than average Americans, ultimately funded by poorer than average Americans? Why does he seem so keen on finding new ways of stealing taxpayer money for them?

Yes, there is a real issue here where we have less dynamism and mobility than we would like and people feel unable to move. If we want to solve that, we can stop having the government bribe people into long term fixed-rate mortgages designed as if to create exactly this problem. At least, as a first step.

Waiving the requirement for title insurance seems somewhat more justifiable, given that it ‘typically pays out only 3% to 5% of premiums.’ That certainly does not sound like a product anyone should buy, let alone one we should force them to buy. Nor does it sound like anything that happens in a remotely free market.

Oh, they say, we can fix the distribution issue, because we are also going to force prices up via paying people $25,000 in ‘down payment assistance’ when buying their first home if they haven’t ‘benefited from generational wealth building associated with homeownership.’

The result of this will inevitably be to put people into homes they do not want and cannot afford, because that bribe is too big to pass up.

Also they plan to ‘fight egregious rent increases,’ in order words to impose rent controls, confiscating private property and destroying the housing stock. Why should a price increase ever be illegal on the federal level?

Reading all this makes one wonder where such people think money comes from and where it goes. Who do they think is paying for all this? How do they think this impacts various markets? Do they have any idea how any of this works, at all?

Here Matt Yglesias goes over some things the federal government could do that might actually help. He says ‘the issue isn’t that the Biden administration doesn’t get it.’ I agree that they get we need to ‘build, build, build,’ but then they go ahead and do all these other things anyway. So while there is one level where they get it, there is another level where they very clearly don’t.

In other rent control news, Emmett Shear has a proposal.

Emmett Shear: Rent control is a transparently terrible idea. But has a city ever tried price caps per square foot on rental housing? If set right, that would at least accomplish the theoretical goal by preventing “luxury” housing, while leaving cheaper housing untouched.

Of course it has all kinds of nasty potential side effects, like any time you intervene in the free market. Wealthy people would on the margin consume more by renting much bigger houses since they can’t spend more per sq ft. But it seems less-horrible.

There is the danger that it drives everything into sold housing rather than rented, but I think that should only impact the higher end. The biggest issue will be variance in prices making the cap wrong locally, I think.

I mean, if the cap is set high and maintained high over time (they tend to drift downward) then this is less harmful than other rent control rules, but only because it applies less often, and where it matters less?

The result is effectively to ban renting out units with sufficiently high value per square foot. If the place is that valuable, it should be easy enough to convert it to a condo or co-op. So that is what would happen. Not a huge tragedy, but rather pointless destruction of all high-end rental stock.

His thinking seems to be that this would ensure that the quality of the housing stock was worse, because that is good, actually?

Alex Krusz: Why is preventing luxury housing good?

Emmett Shear: Makes the housing that gets built more affordable.

I mean, sure, if you want to destroy the housing stock of a city only down to some threshold, then you can use a pinpoint form of rent control that substitutes only for highly selective aerial bombing. That does not make it a good idea, unless it is a compromise that kills other worse rent control.

I wrote that a weeks ago. Speaking of which…

Despite recent Supreme Court decisions saying he would be immune from prosecution, Biden is determined not to use aerial bombing to level our cities.

Instead, he is proposing a second best solution.

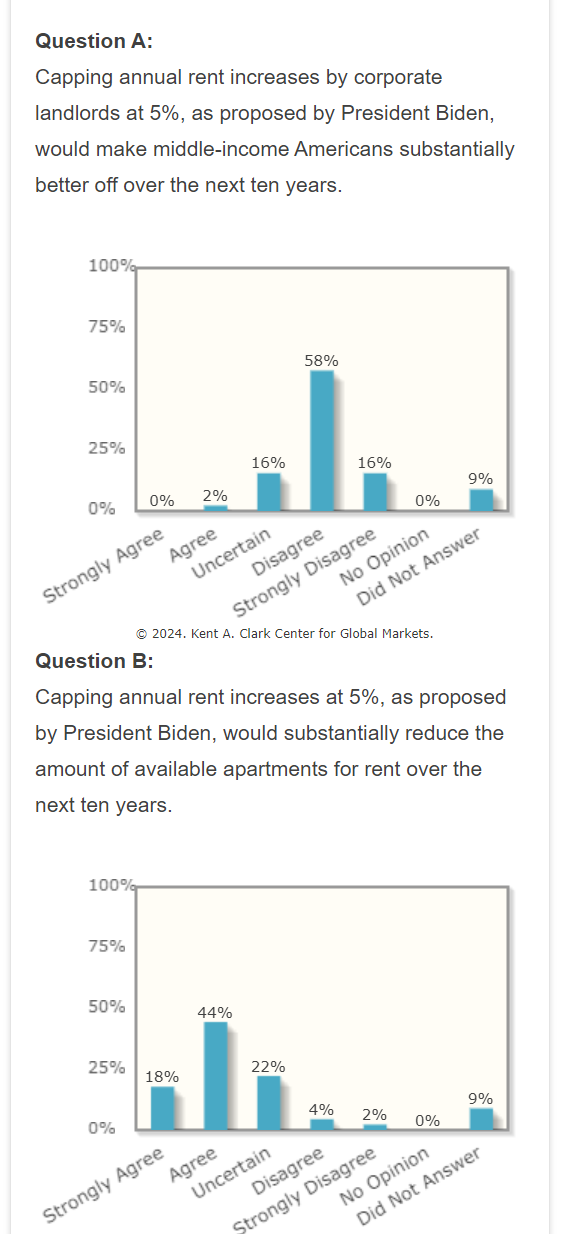

Joe Biden (well, his Twitter account): I’m sending a clear message to corporate landlords: If you raise rents more than 5%, you should lose valuable tax breaks.

Families deserve housing that’s affordable – it’s part of the American dream.

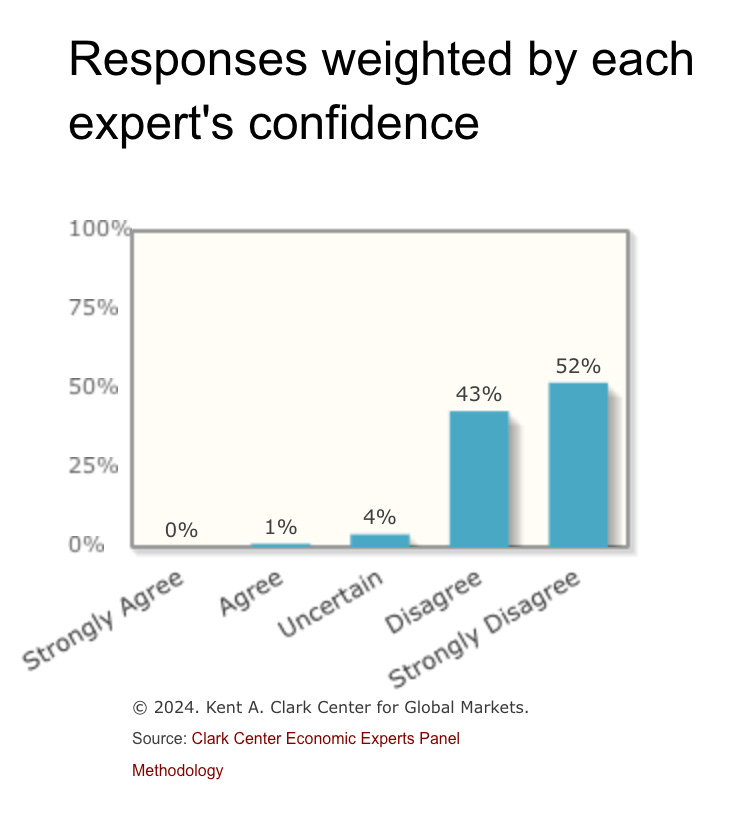

Jason Furman (top economist, Obama administration, quoted in WaPo): Rent control has been about as disgraced as any economic policy in the tool kit. The idea we’d be reviving and expanding it will ultimately make our housing supply problems worse, not better.

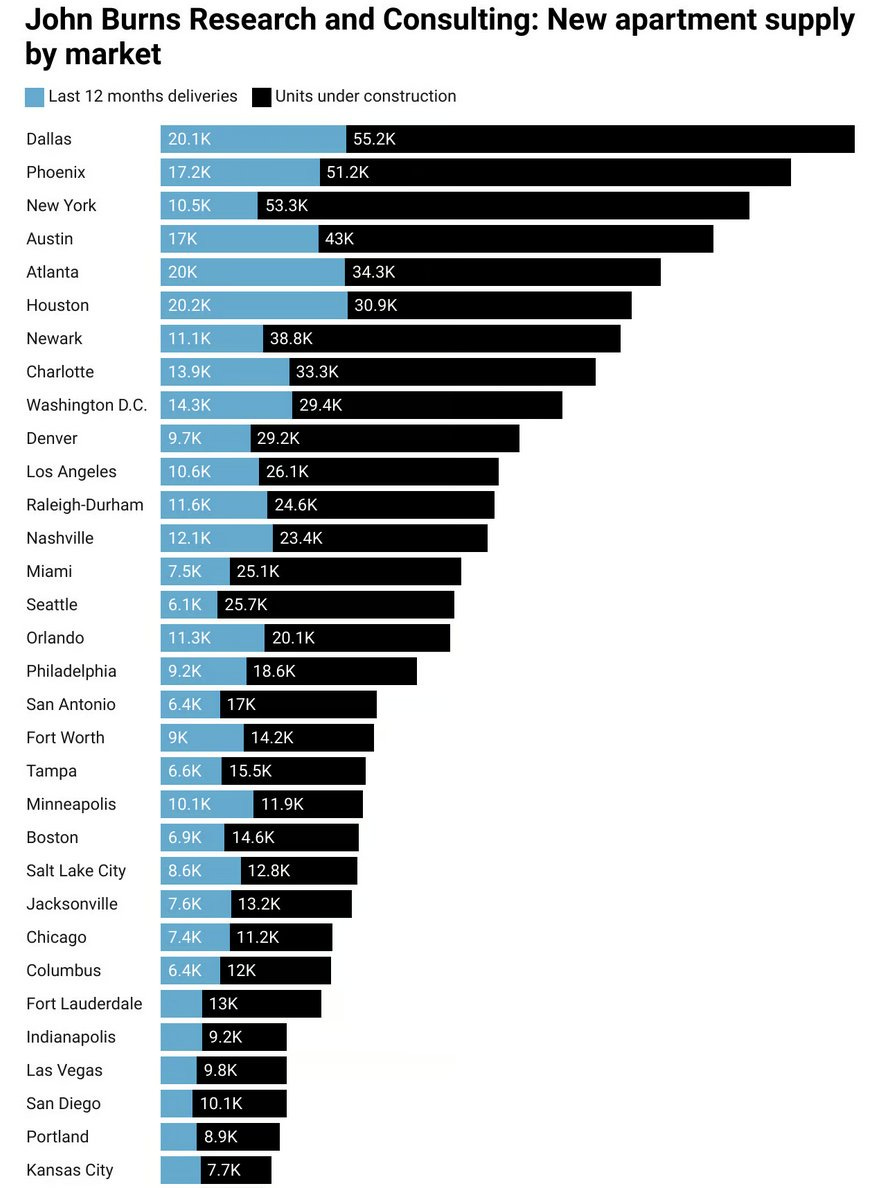

Jeff Stein and Rachel Siegel (WaPo): White House officials, however, say the rent cap would give short-term relief to renters before an estimated 1.6 million new housing units become available in two years, which should also drive down prices. (The Biden plan would only apply to rental units for two years, by which point, in theory, this fresh supply would alleviate costs.)

The extent to which those defending this rule simply do not believe in private property boggles the mind.

“It would make little sense to make this move by itself. But you have to look at it in the context of the moves they propose to make to expand supply,” said Jim Parrott, nonresident fellow at the Urban Institute and co-owner of Parrott Ryan Advisors. “The question is: Even if we get all these new units built, what do we do about rising rents in the meantime? Coming up with a relatively targeted bridge to help renters while new supply is coming on line makes a fair amount of sense.”

Sigh.

The ‘good’ news is that:

-

This will never pass.

-

This is implemented in a triply ham fisted way to mitigate its worst impacts.

-

Limited to removal of a tax break.

-

Limited to landlords with 50+ apartments.

-

Limited to a two year period.

-

Limited to already constructed apartments.

The last two give the game away.

Biden’s team realizes that if you imposed rent control on newly constructed apartments, people would build far fewer rental apartments.

Their solution? Don’t (yet, today) propose confiscating the wealth of those who create the housing stock we need tomorrow. Instead (today) confiscate the wealth of those who already created housing stock. They’re stuck.

Then, tomorrow, we can discuss the housing stock we build today.

I say ‘Biden’s team’ because Biden does not seem to know what his policy is.

Eric Levitz (video at link): Biden has not just been having difficulty with extemporaneous speaking. He’s also been struggling to read speeches off a teleprompter. Here, he mistook text promising a 5 percent cap on rent increases for a cap on rent increases larger than $55.

Paul Graham: This is painful to watch. Rent control is already a stupid idea, but he misreads the 5% on the teleprompter as $55. That means he doesn’t even remember what his own policy is.

Jesse Singal: I 100% think this is not because he is lying but because he is not capable of reading off a teleprompter in a coherent, accurate way at this point.

Alex Tabarrok: Biden is doing everything he can to drive me away.

Terrible policy that he flubs by reading 55 off the teleprompter instead of 5%.

This is different from confusing names. This is a rather large conceptual error that one only makes if one is reading off a teleprompter without understanding the words. It would also be a complete disaster to actually cap rent increases at $55, which in major cities would often be well below inflation and is remarkably close to a de facto ban on rentals.

Whereas a 5% cap, with 3% inflation, for only a two year bridge period? Shouldn’t that be Mostly Harmless, as the advisors claim?

Except, of course, builders of real estate can see that future, too. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, can’t get fooled again.

If I am a landlord, I act as if this rule is permanent. There is nothing so permanent as a temporary government program. So I am going to game it out as if it was permanent.

Even if it is not permanent, the seal has been broken. So I need to anticipate that my temporary rental agreement could turn into a permanent seizure of my property, at any time.

(Indeed, I wonder the extent to which even proposing this policy as the President does great harm, for exactly this reason.)

The 50+ apartment rule is, if the tax break is substantial, a de facto a ban on landlords that long term own 50+ apartments in hot rental markets.

What would inevitably happen if this was implemented and seemed likely to be permanent? When the market rent increases are substantially above 5%, the large landlord will sell the relevant apartments to new smaller landlords. Then the smaller landlord raises the rent.

Then, probably, once things cool down or the rent has been made safely high enough, if things are likely to remain cool, they likely sell those apartments back to large landlords again.

So this involves a lot of real estate commissions and negotiations and weird contracts, and tons of extra work and paperwork, and wiping out of landlord reputations and relationships that tenants could count on before, to get back to where we started.

In the case of buildings with more than 50 apartments, this gets somewhat awkward, as the building ownership will need to be divided. In some cases, they’ll give up and convert to condos.

Also, of course, everyone will raise all rents somewhat higher, in anticipation of perhaps needing to raise them in the future, and to compensate for the related expenses.

And also large landlords will stop trying to improve apartments, and start skimping on maintenance, as they always do under rent control.

That’s kind of a ‘best case’ scenario for implementation.

The bad scenario is that this creates pressure to lower the 5% cap, or inflation gets higher so as to effectively lower it, and there is pressure or worries about pressure to extend the rule to smaller landlords and future buildings soon. Or perhaps federal rules on what a ‘fair base rent’ would be in the first place.

Once rent control starts, it gets stricter and more oppressive. So anticipating that, expect somewhat of a decimation of the rental housing stock.

So in short: The impacts would be severe, but nowhere near as severe as the full version. But if this led or looked like it would lead to the full version, it could quickly end up being the full devastation version, wrecking all our rental markets. Who wants to risk renting a place when the Federal government might decide to effectively confiscate your property whenever it feels like it?

As a reminder, what does rent control do? Alex Tabarrok links to Kholodilin’s comprehensive review of the literature. Things with a + go up, things with a – sign go down.

What about Trump’s housing policies?

A long time ago I had high hopes in this area. Whatever his other faults, however many crazy tariffs he might impose, Donald Trump is famously a real estate developer. He built, baby, he built. So it seemed highly plausible he would adopt policies helping real estate developers to develop real estate, whether or not that involved massive graft.

Then it turned out, no, Trump instead did things like warn that Democrats wanted to ‘destroy the suburbs’ by building housing where people want to live. Either way, it did not seem like any sort of priority.

Matt Yglesias: Trump’s administration was initially pushing zoning reform but then some time in 2019 he fell in love with the idea that Cory Booker’s zoning reform bill would destroy the suburbs and they flip-flopped. But the man was a professional urban infill builder at one point, he knows.

Bloomberg interviewed Trump this week, in which sometimes substantive questions are asked (and at other times not) and then Trump is given room to talk, so we got in some questions about actual economic policies. It was a good reminder of how he thinks about all that.

The transcript includes fact checks, which is fun, but they missed some spots, including the whopper in the very first line.

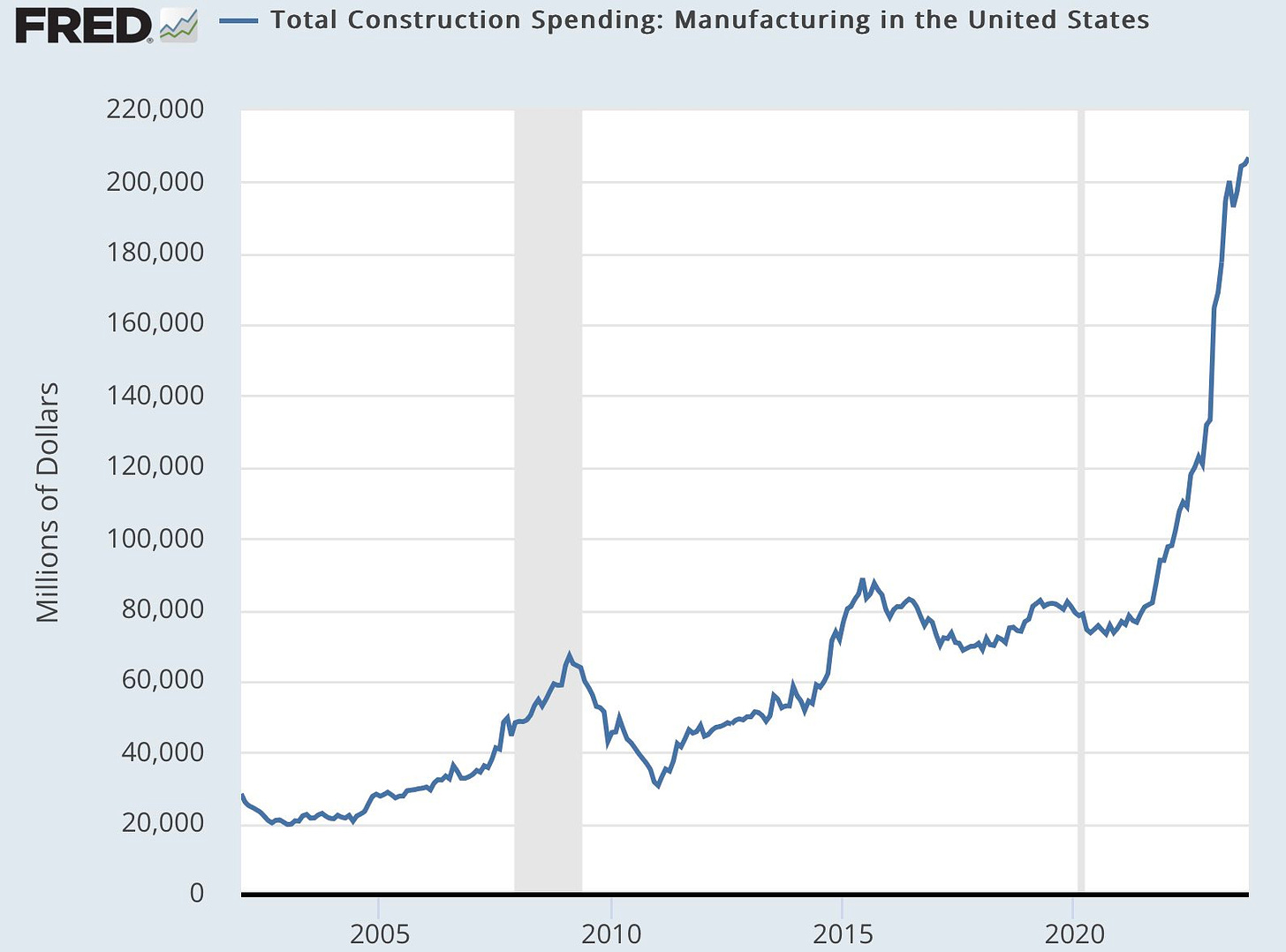

Donald Trump: Well, I think manufacturing is a big deal, and everybody that runs for office says you’ll never manufacture again.

Even if you change ‘everybody’ to the implied ‘most people’ this is still obviously false. Joe Biden very much has said the opposite in both of his campaigns and with his policies. Many candidates at all levels are constantly saying the opposite.

I would not normally mention it, except as a first line in a ‘fact checked’ interview I find it pretty funny. The actual fact checks are also often highly amusing. You can learn a lot by thinking about how Trump decided which claims and numbers to pull out of [the air].

Also, if you are a thin guy, and you ever meet Donald Trump, drink a Diet Coke, purely to blow his mind.

So on housing, what did we learn?

Q: I wanted to ask you about the housing market because that is a huge cost to people. The mortgage rates are so high, there is a huge housing supply problem right now. What is your plan to make housing more affordable for people?

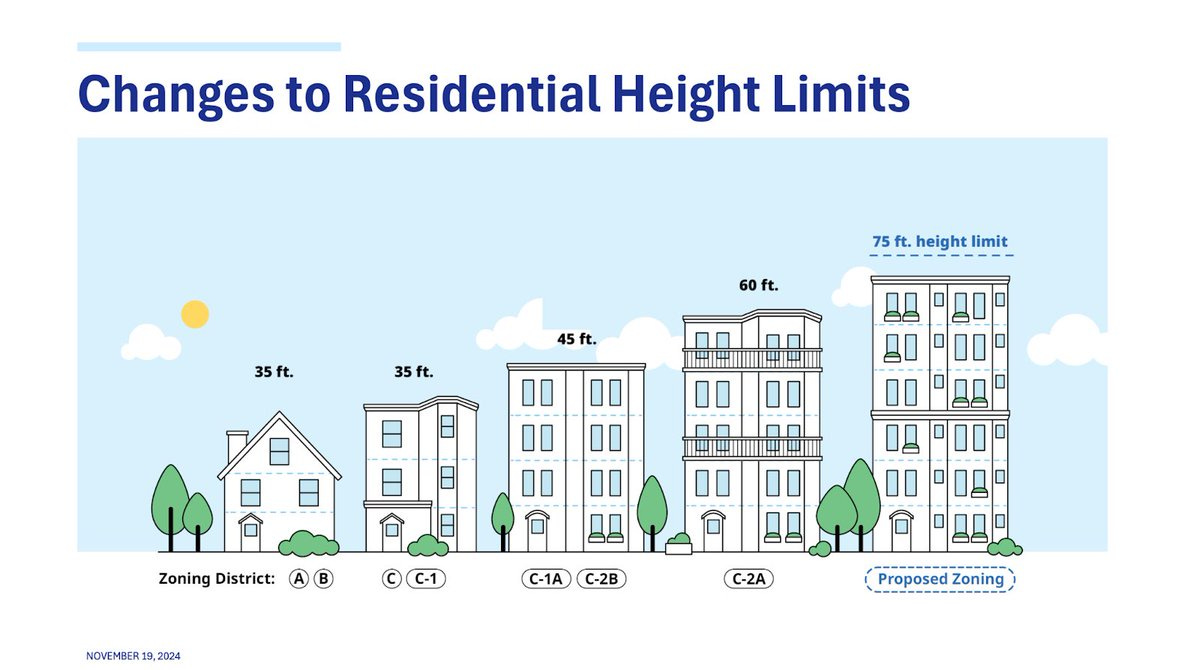

Donald Trump: That’s a very good question. So 50% of the housing costs today and in certain areas like, you know, a lot of these crazy places is environmental, is bookkeeping, is all of those restrictions. Building permits. Tremendous [restriction]1.

Plus, they make you build houses that aren’t as good at a much greater sum. They make you use materials that are much less good than other materials. And the other materials are, I mean, you’re talking about cutting your [permits] down in half. Your permits, your permitting process. Your zoning, if—and I went through years of zoning. Zoning is like… it’s a killer. But we’ll be doing that, and we’ll be bringing the price of housing down.

The biggest problem with housing now is that you have interest rates that went from 2.5% interest to 10%. Can’t get the money. So, you know, I don’t know if you can stop at 10 because if you can’t get the money, that means it’s higher. But people, they can’t get financing to buy a house.

Other than calling for lower interest rates at various points, Trump does not take this or other opportunities to talk about any actual actions on housing. He does not actively talk rent control or subsidizing demand, but neither does he back up his complaints about permitting and regulations with any plans or intentions to fix that.

No, he’s focused on getting rid of regulations in other areas. Like AI. Of course.

There are of course other things going on with the Presidential candidates than the places where I focus. But I leave such discussions to others.

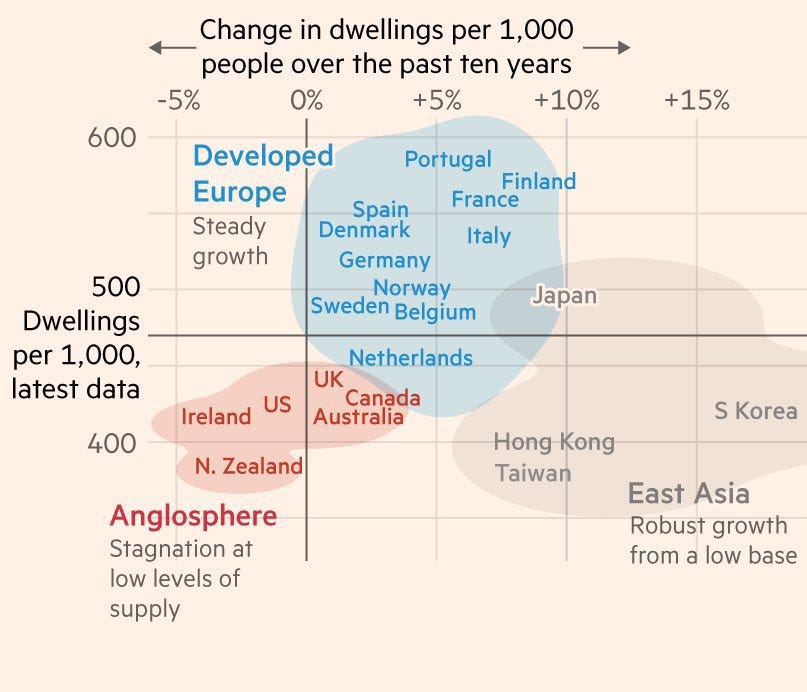

The Anglosphere has a big problem.

Gary Winslett: Never ask a man his salary, a woman her age, or an Anglophone country how it’s housing policy is going.

There is a solution.

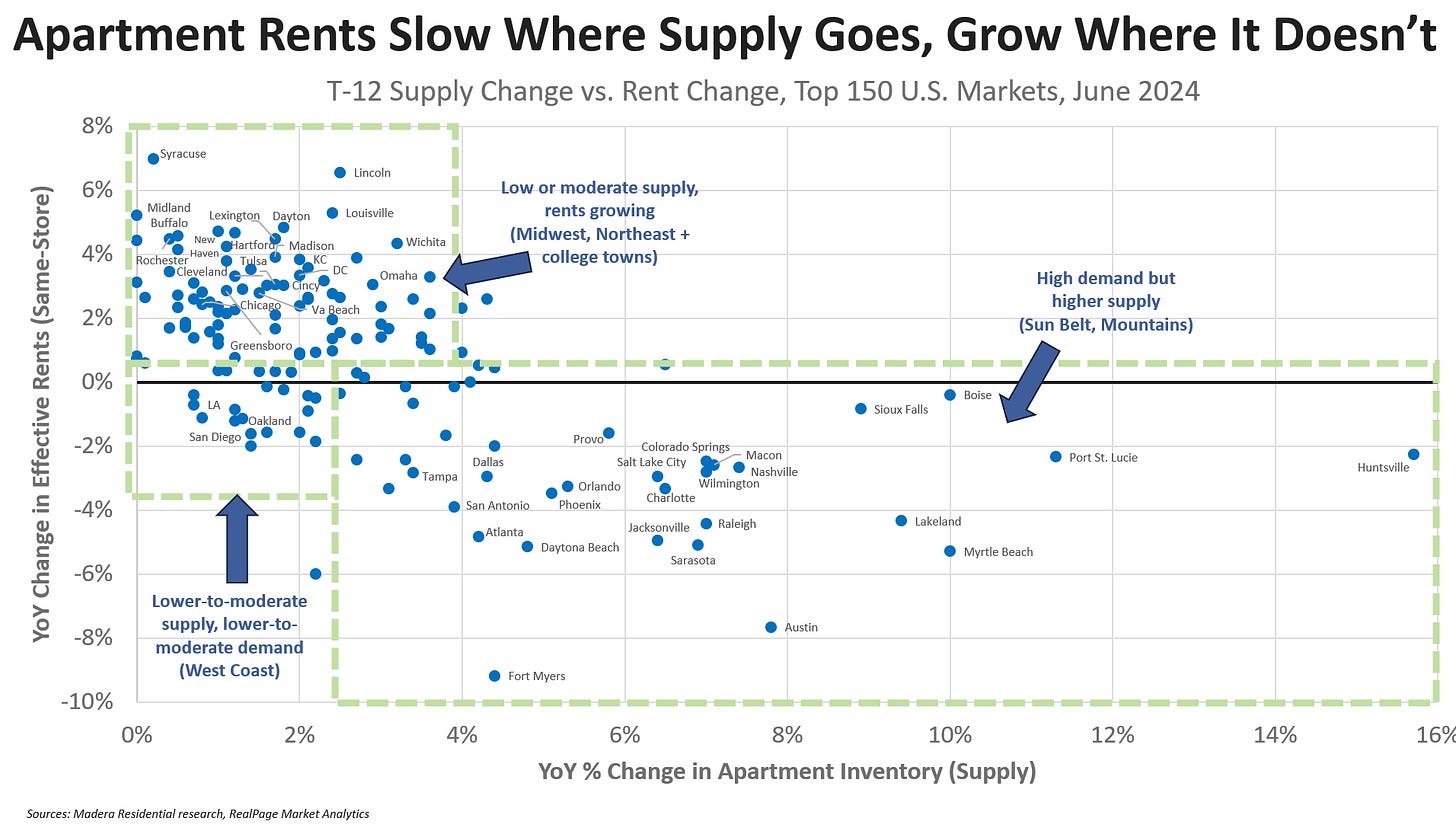

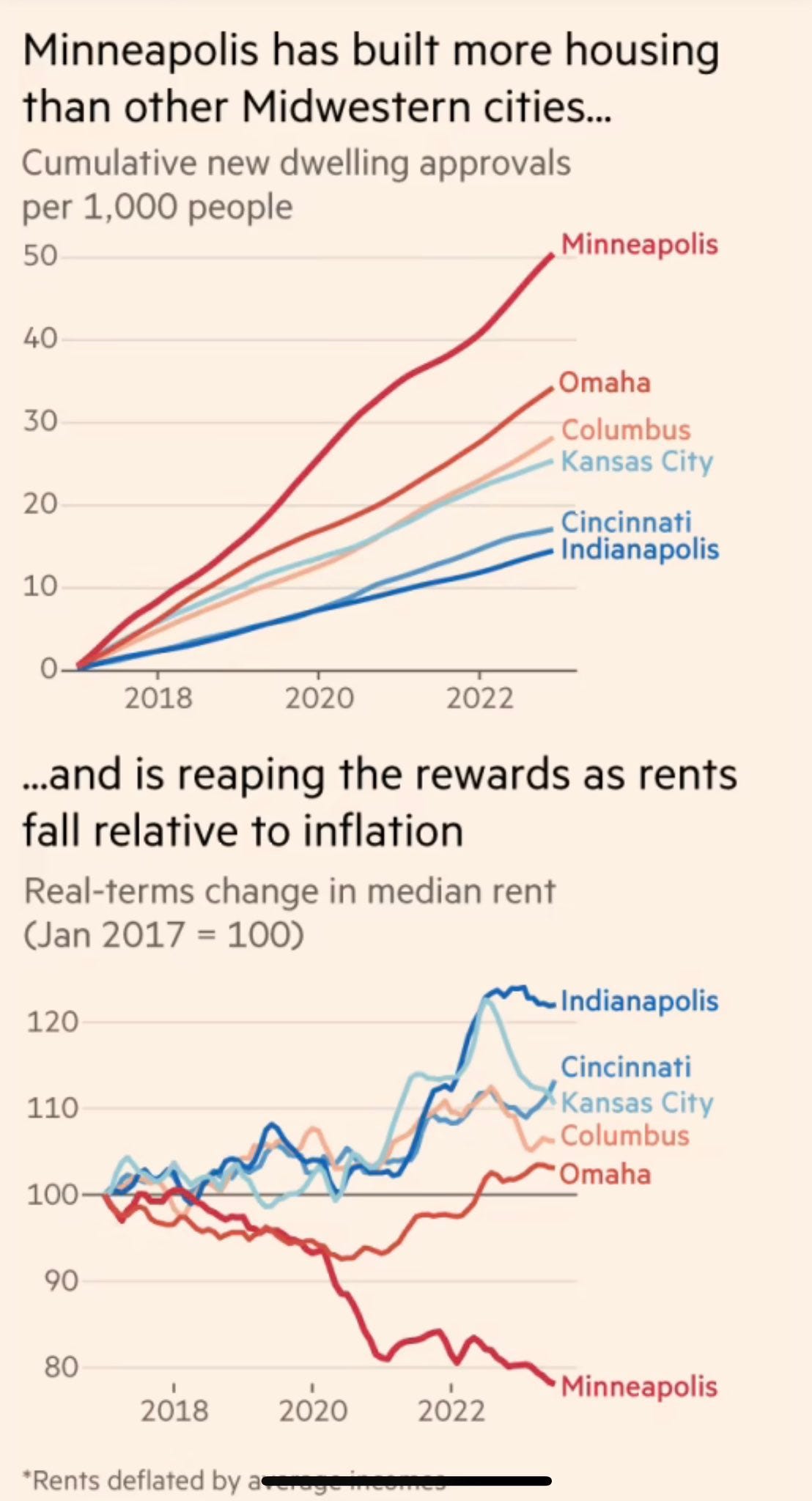

Darrel Owens: Evan Mast did a study, highlighted by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, on the city’s flat & decling rents, finding that for every 100 market rate apartments built, 70 existing apartments were freed up in low income neighborhoods. What lessons on gentrification can be extracted here.

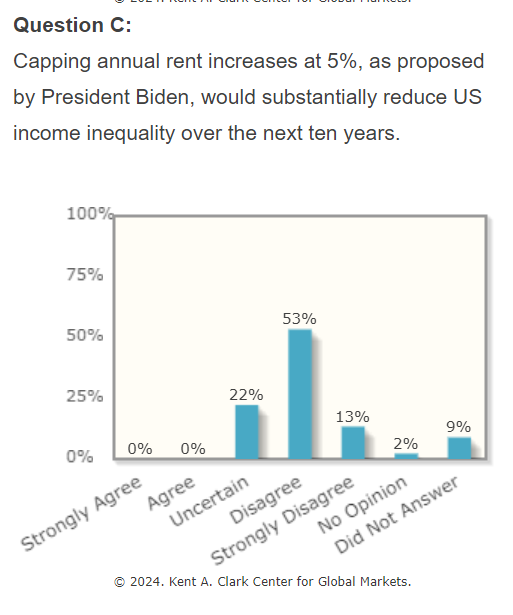

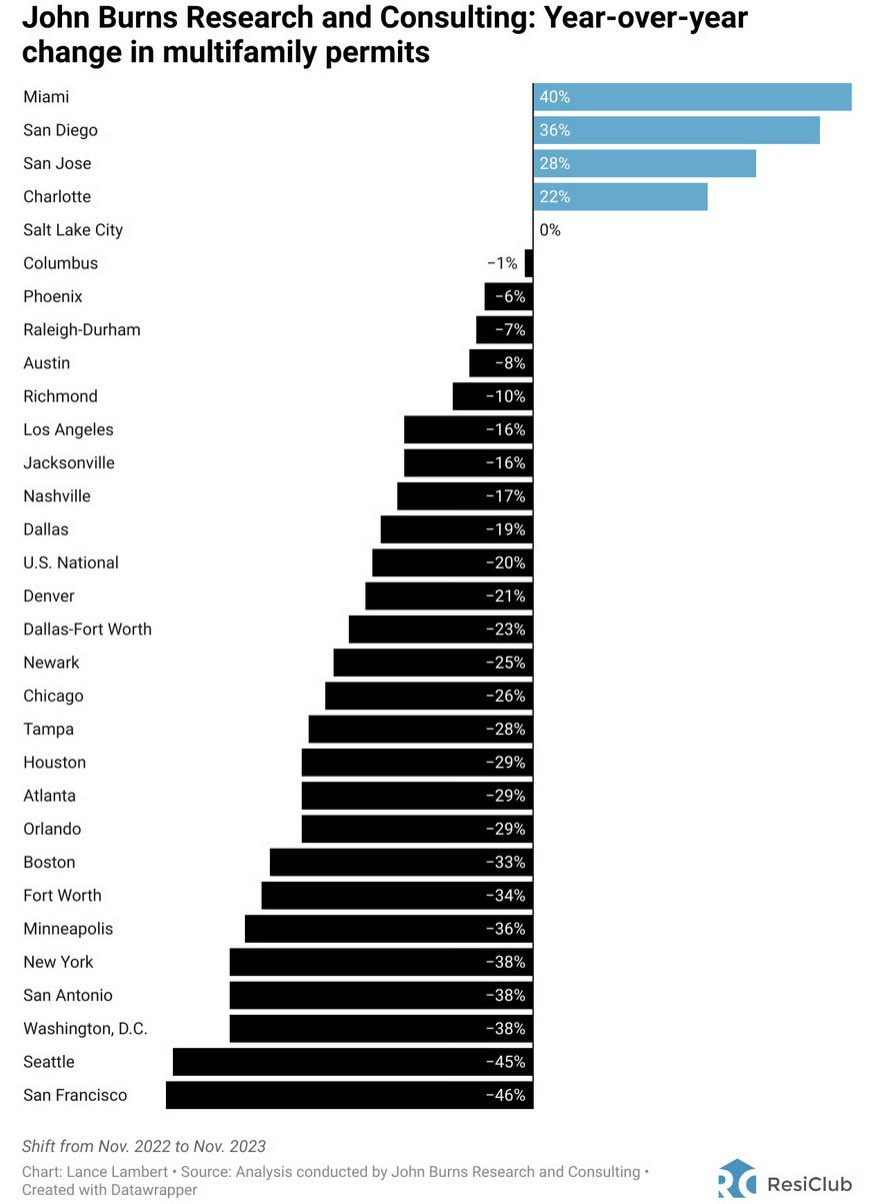

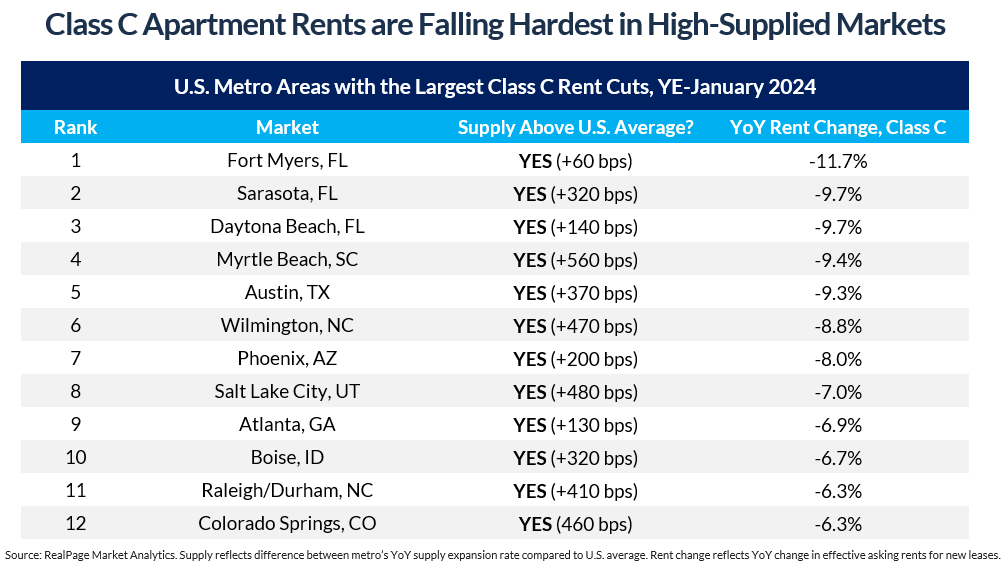

Scott Lincicome: ICYMI: I review the latest evidence of “filtering”, which shows that places like Austin & Raleigh that build more housing have lower prices/rents for ALL classes of homes/apartments (not just “luxury” units). But I also caution that true US Housing Abundance is still a ways off.

The problem is that people locally tend to oppose it.

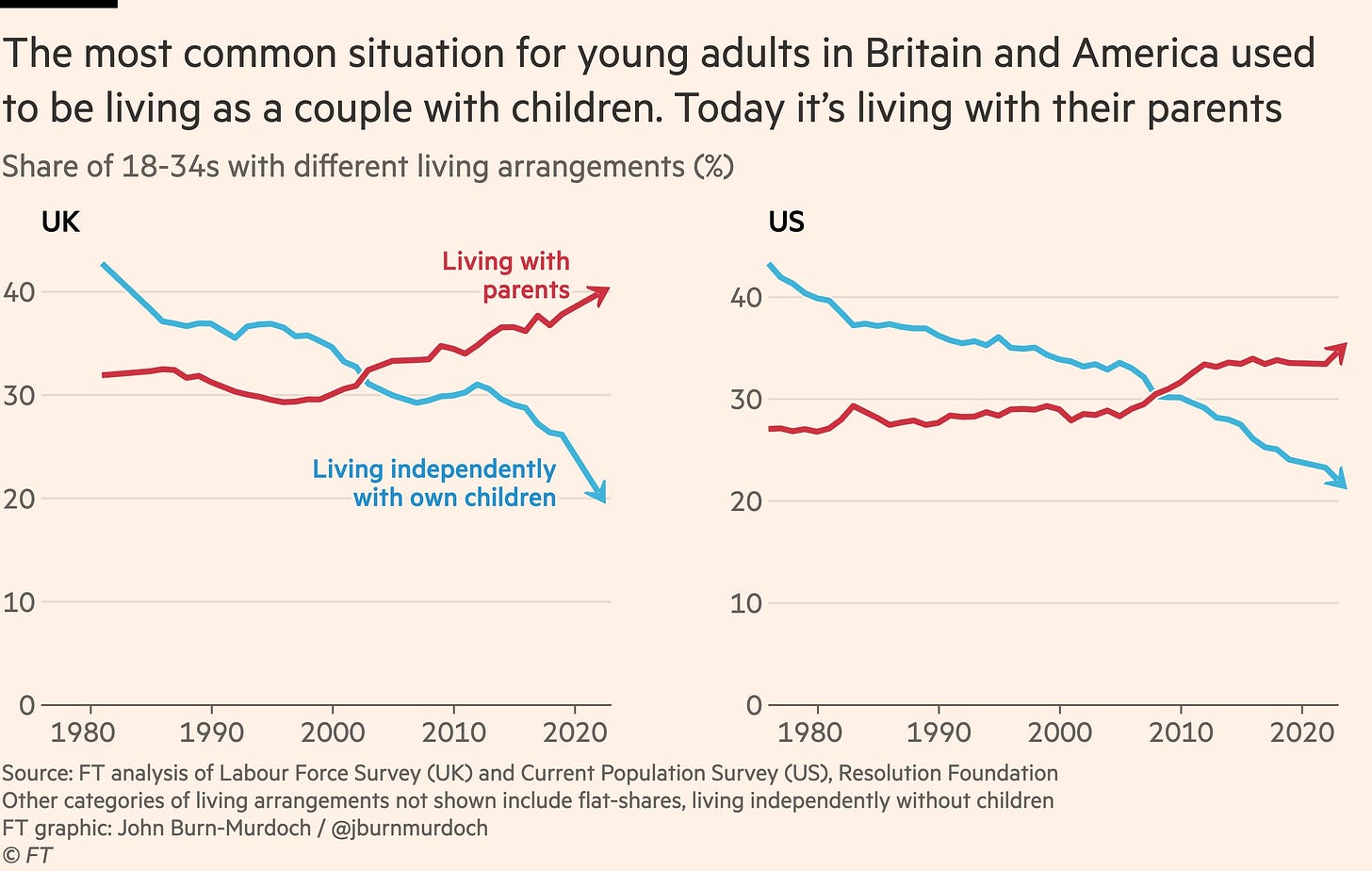

Jacob Shamsian: I need to read a New York mag essay titled “NYC or kids?” that explores the tension between being able to afford this city vs building a family.

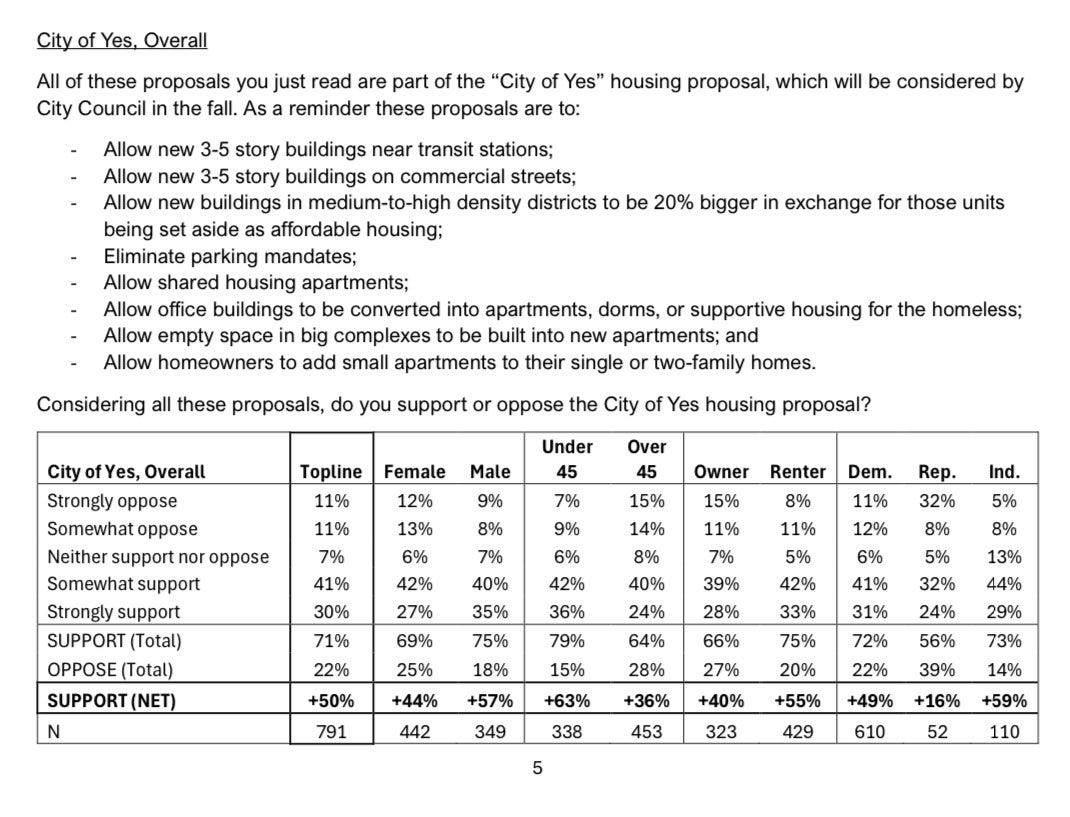

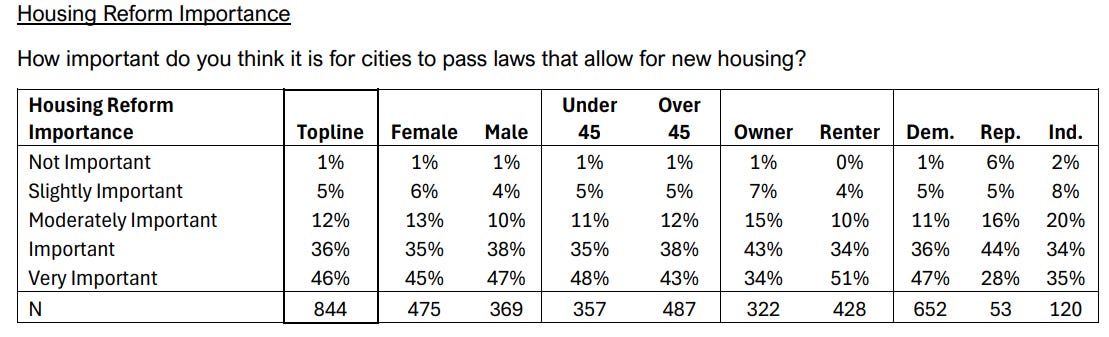

Matthew Yglesias: The two things I hear about ~every affluent city:

1) Voters’ number one concern is housing affordability and they are desperate for politicians with bold solutions

2) Broad, city-wise relaxation of land use rules would be toxic and unpopular

Despite my reputation, I actually do think there’s a lot of stuff more market rate construction can’t solve.

But “middle class people with decent jobs can’t afford a bigger home / more convenient location” is like THE thing you can fix with pure deregulation.

Is ‘affordable housing’ better than market-rate housing?

I would bite the bullet and say ‘affordable housing’ is simply some combination of:

-

An inefficient tax on building or owning housing.

-

An inefficient allocation of housing to those who value it less.

-

An inefficient allocation of capital, where we massively subsidize a few people.

-

An inefficient lowering of the quality of the housing stock.

-

An inefficient way for people to seek rent or feel righteous. Sometimes both.

I put affordable in quotes because what people mean by ‘affordable housing’ is ‘housing where we allocate below-market units to those who have our favor’ rather than ‘the market price of housing gets more affordable.’

I am all in favor of that second one. Ideally the prices decline sufficiently, and we allow the renting of sufficiently small units, that housing becomes highly affordable.

There are three legitimate purposes this is trying to address.

-

We need to tax something. Residential real estate makes sense to tax.

-

We want to do progressive redistribution. We can write that into the tax code.

-

We would like some less good apartments to exist. We can remove regulations.

Thus, we have much better options than this affordable housing.

I realize this is not a consensus view.

Also one could argue that current convention allows requiring that a developer provide ‘affordable housing,’ but it does not allow the state to require that developer write the city a large check or agree to take on higher property tax rates. So while affordable housing is never first best, it could in practice often be superior on the margin to the alternatives.

What should be clear to everyone is:

-

More market rate housing is good.

-

More non-market rate housing is good.

-

A combination of more of both is also good.

-

The problem is too little of one, not too much of the other.

Matthew Yglesias: We have some of the longest-standing YIMBY organizing efforts here in DC, but there isn’t really a single strong pro-housing person on the Council championing ambitious legislation and big ideas.

It’s very disappointing.

Martin Austermuhle: I mean, D.C. has by no means been perfect, but there’s been loads of housing construction in recent years, and the city has put more money into affordable housing than most comparable jurisdictions. The D.C. Council also passed an updated Comp Plan.

The main criticism has been that D.C. has allowed too much market-rate housing, hasn’t invested enough in fixing public housing, and hasn’t done enough to enforce existing tenant protections. And some criticize the continued existence of single-family zoning.

Matthew Yglesias: Yes this is what I mean. The dialogue in DC is about whether there is too much market-rate housing when we should be arguing about how to create dramatically more of it. Right now, ~zero people on the Council are championing the cause.

Right now the Council is debating how much to raise taxes and how much to cut services in order to address a big fiscal crunch. The best solution is to substantially roll back anti-housing regulations and grow the economy.

As in forcing you to include ‘affordable’ housing, meaning misallocated mispriced housing, in order to build new housing.

It is poorly named, since its primary purpose is to exclude housing construction.

Dan Bertolet: HB 1110 requires cities to upzone for middle housing, but does not require inclusionary zoning. IZ is particulary harmful to small-scale housing and Seattle data shows it. To avoid undermining HB 1110, Seattle must not impose IZ on middle housing.

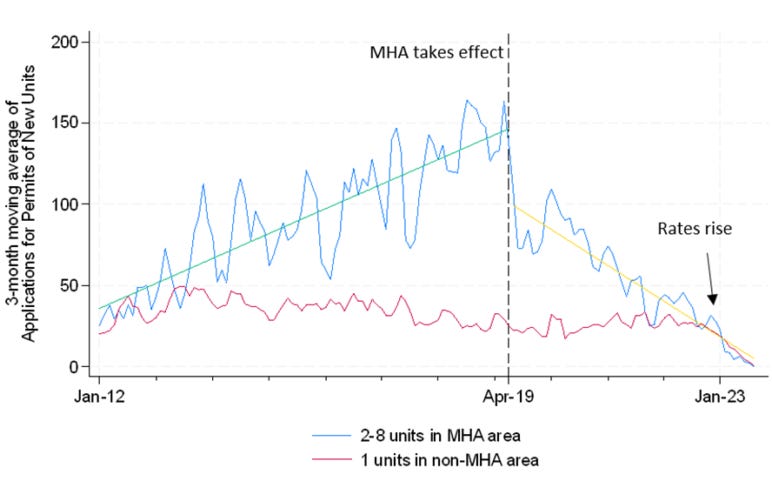

Aaron Green: Look at how housing production plummetted after inclusionary zoning took effect. Now the people who would have lived in these new buildings are out competing with others for existing rental stock, pushing rents up for everyone. IZ makes the housing crisis worse.

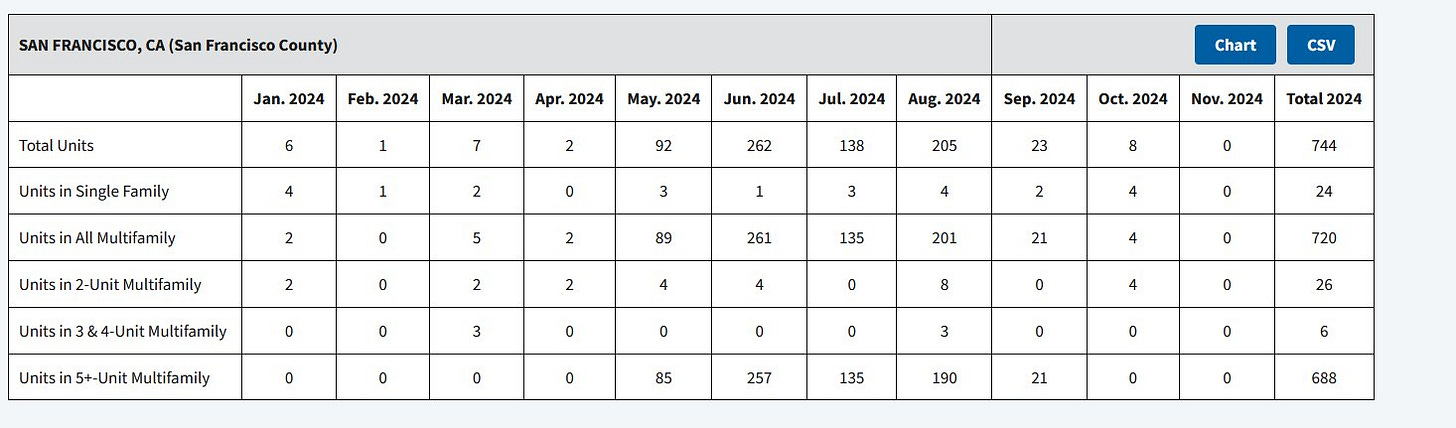

As always, San Francisco found a way to make this more of a disaster. The city tried to specify a wide variety of conditions for who can rent its ‘inclusionary’ units and rules on how much owners can charge, and the whole thing is such a mess that 80% of the units are sitting empty. The city fails to deliver a tenant they are willing to let lease the apartment, and are unwilling to let someone else rent it instead. Chris Elmendorf suggests some obvious potential fixes, via giving some window for ‘qualified’ renters to appear after which the units can be leased to a market rent tenant. That would work, but misunderstands what the city cares about.

Offered for contrast and humor, because yes you can do so much worse than rent control, that challenge has been accepted successfully: Here is the Guardian attempting to blame the UK’s housing shortage, caused of course by their ‘never build houses’ policy, to not the absurd lack of supply but rather on ‘landlordism.’ The proposed solution is ‘landlord abolitionism.’

I’ll hand this one off. Iron Economist has various amusing counterpoints, some of which you know already, some details you likely don’t.

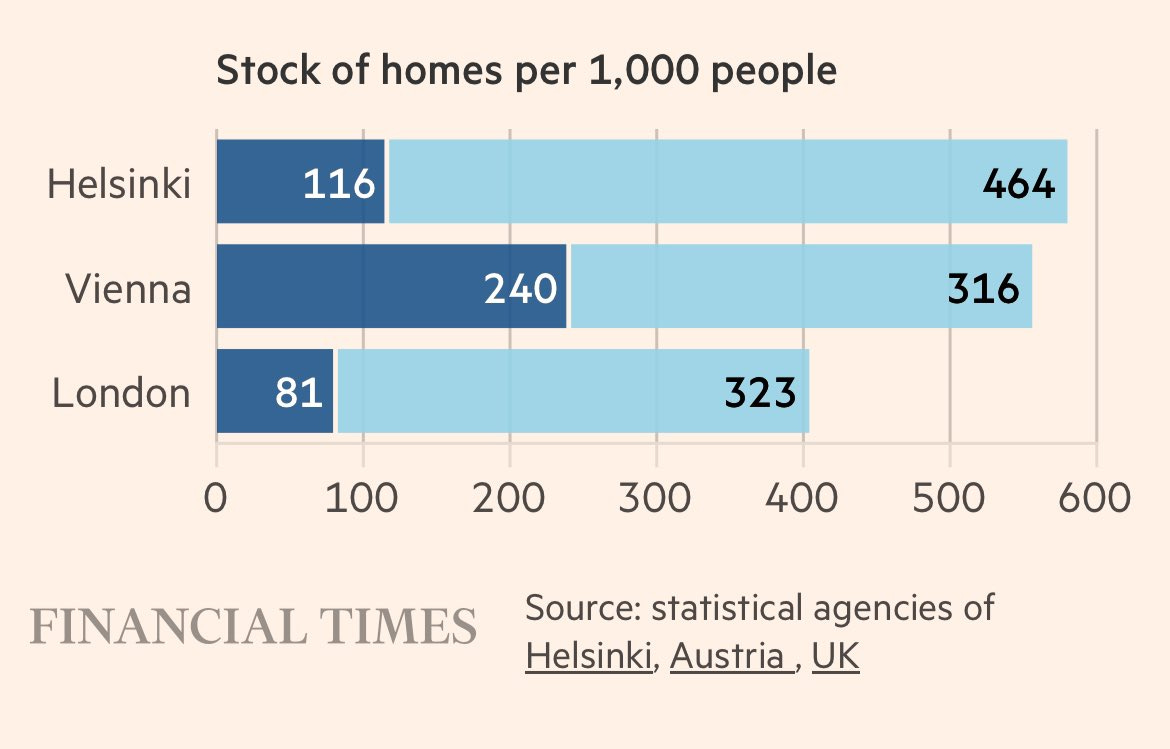

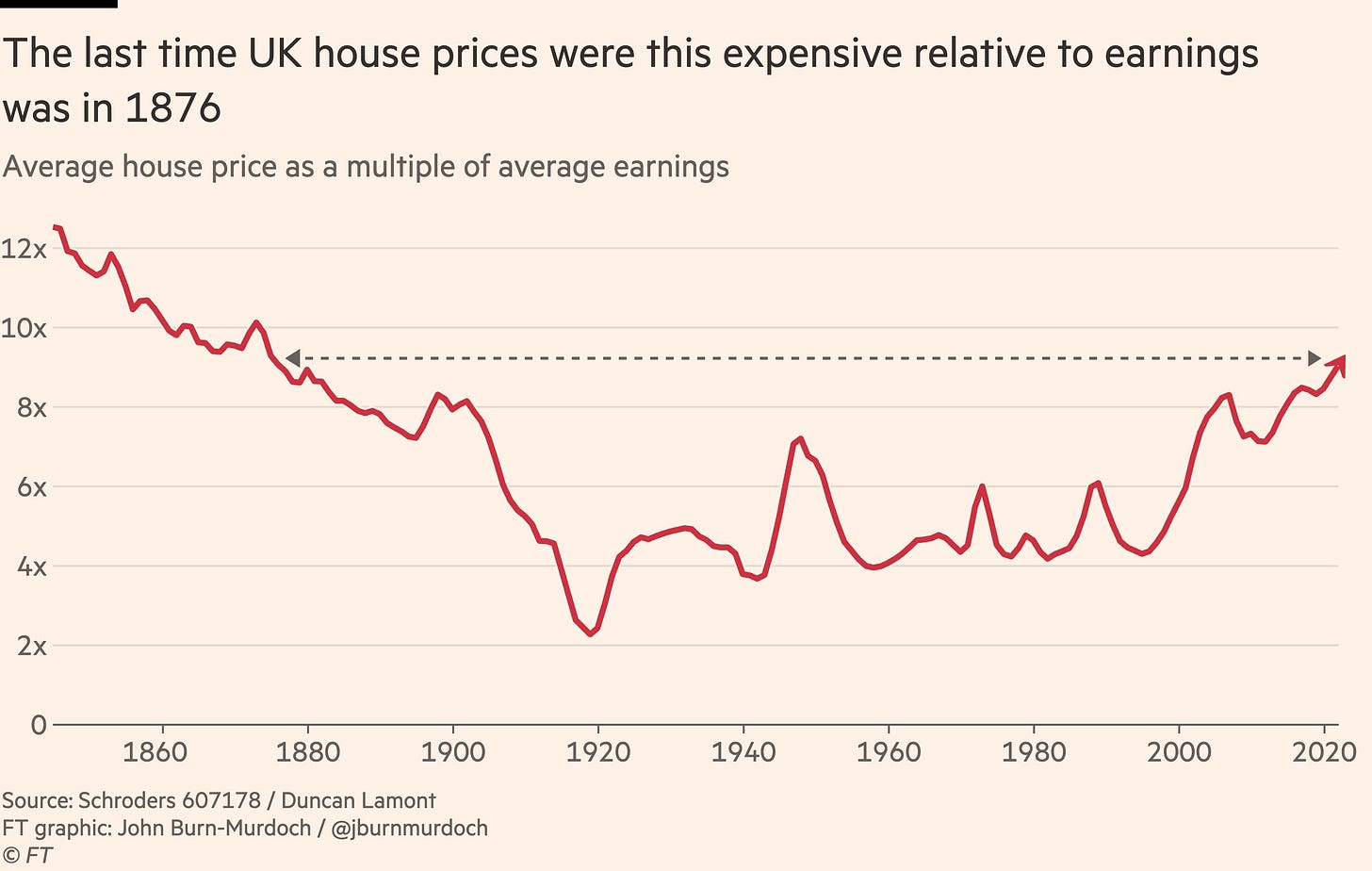

The UK really does have it far worse than us on housing.

Hunter: The UK has a deep state and it’s the planning system. If you can’t build dense housing in the North London Business Park then you’ve made it illegal to build dense housing. London has the worst housing crisis in the world.

The current planning system should be utterly abolished.

Armand Domalewski: It blows my mind that UK politics is not an endless, 24/7 screaming match about the housing crisis. London has Detroit wages and San Francisco rents and yet people are still anxious that it is adding too much housing.

Remember, though, it can always get worse.

Scott Lincicome: Yiiiiiiikes.

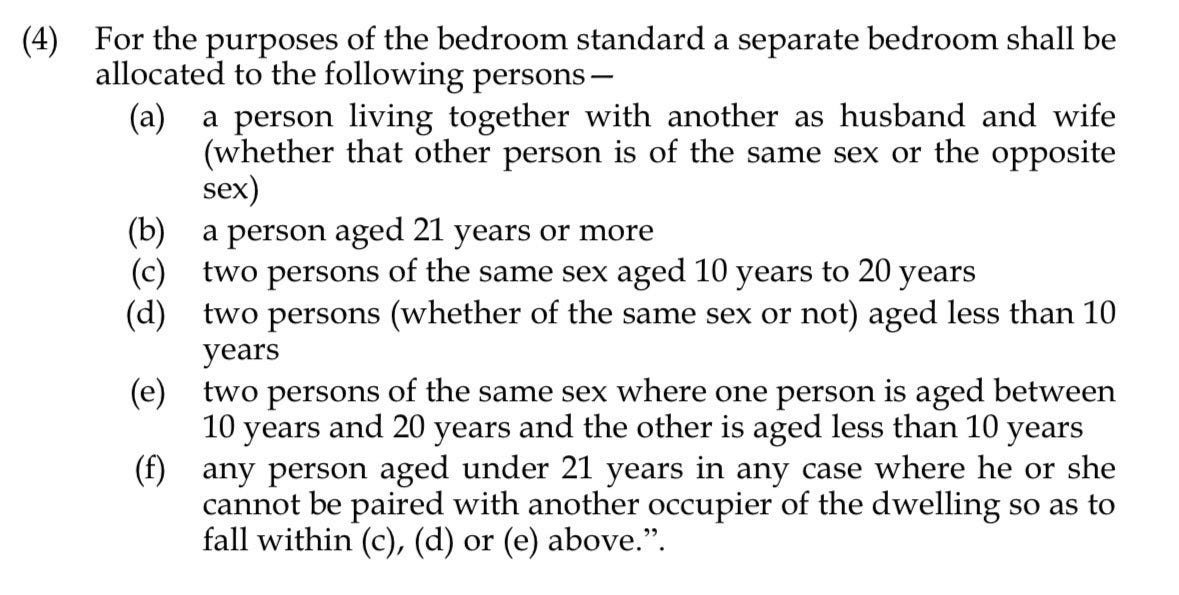

Alec Stapp: New degrowther idea just dropped in the UK: Instead of making it legal to build more housing, they’re just gonna… checks notes… reallocate the spare bedrooms in “under-occupied” houses.

Forest Ratchford: This reminds me of a story my Polish friend told me that during communist period, when his parents went to ask for permits to expand their house the government said if they did they would relocate another family to live with them.

Symon Pifczyk: Funny. In Poland and the USSR, the government would really do this but mostly because of war time damage. It was universally agreed that it’s temporary and housing construction must solve this issue. The UK wanting to do this just so that they can avoid skyscrapers around is wild.

Arthur Boreman: My God we did need the 3rd amendment.

Stefan Horn: I’ve written a new piece for the @IIPP_UCL blog: Meeting housing needs within planetary boundaries requires opening the black box of housing “demand.”

The key idea of the paper and research agenda is that housing can be used very differently: 1) to meet the housing needs of the population, and 2) as a luxury good or status symbol. Housing policy is typically about achieving 1).

The central tool to deliver housing policy has been to “just build more homes”. However, it has been shown that this is both ineffective and resource-intensive. We therefore take a step back to look at the entire housing stock.

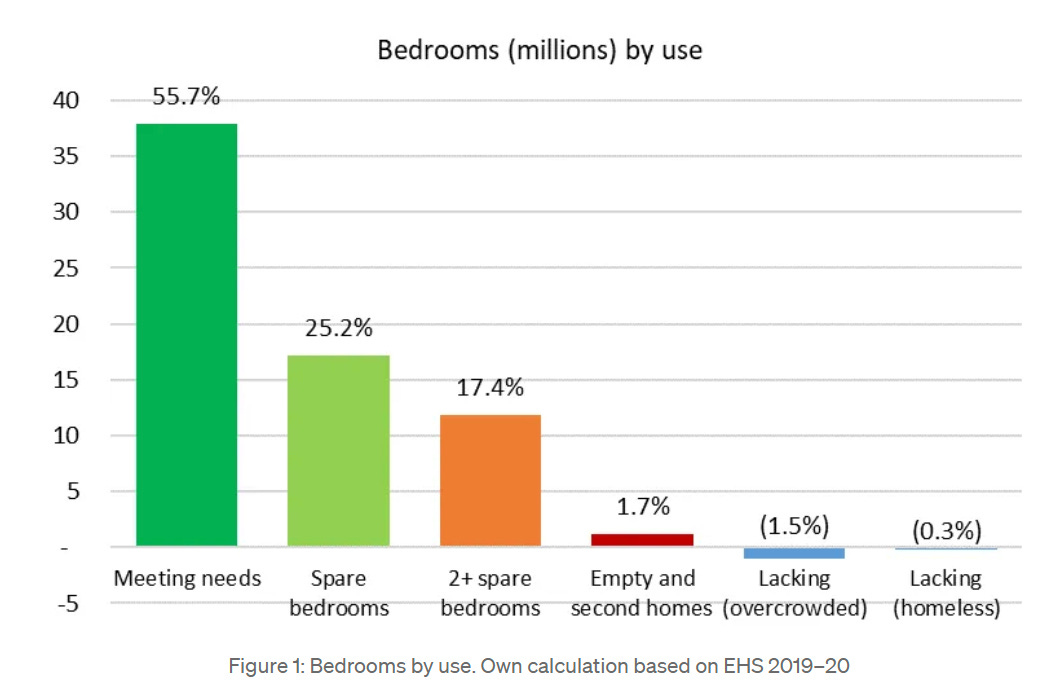

It turns out that, in England, there are already more than enough houses to meet housing needs. But a large part of the housing stock is not used to meet housing needs. Around 19% of bedrooms in England are second or further spare bedrooms.

You see:

Gabriel: ngl telling people that the government is going to take away your spare bedroom instead of allowing the redevelopment of crumbling buildings from the 80s into medium density mixed use housing has gotta be one of the worst political strategies ever conceived in a democracy.

Yoni: it’s so much worse than that. “in NIMBY england your teens have to share a room.”

Sam Bowman: This surprising result comes from using a definition of “spare bedroom” that, among other things, describes two teenagers having separate bedrooms as involving a “spare bedroom”, because the teenagers could be sharing one of the rooms instead.

So, yeah, do remember that it could be worse.

Or you could look at Stockholm, where a powerful tenants’ union holds rents are much as 50% below the market, and wait lists for rent controlled apartments average 20 years. By the time you get to the front of the queue, you probably already own a home. But who are you to turn down such a deal?

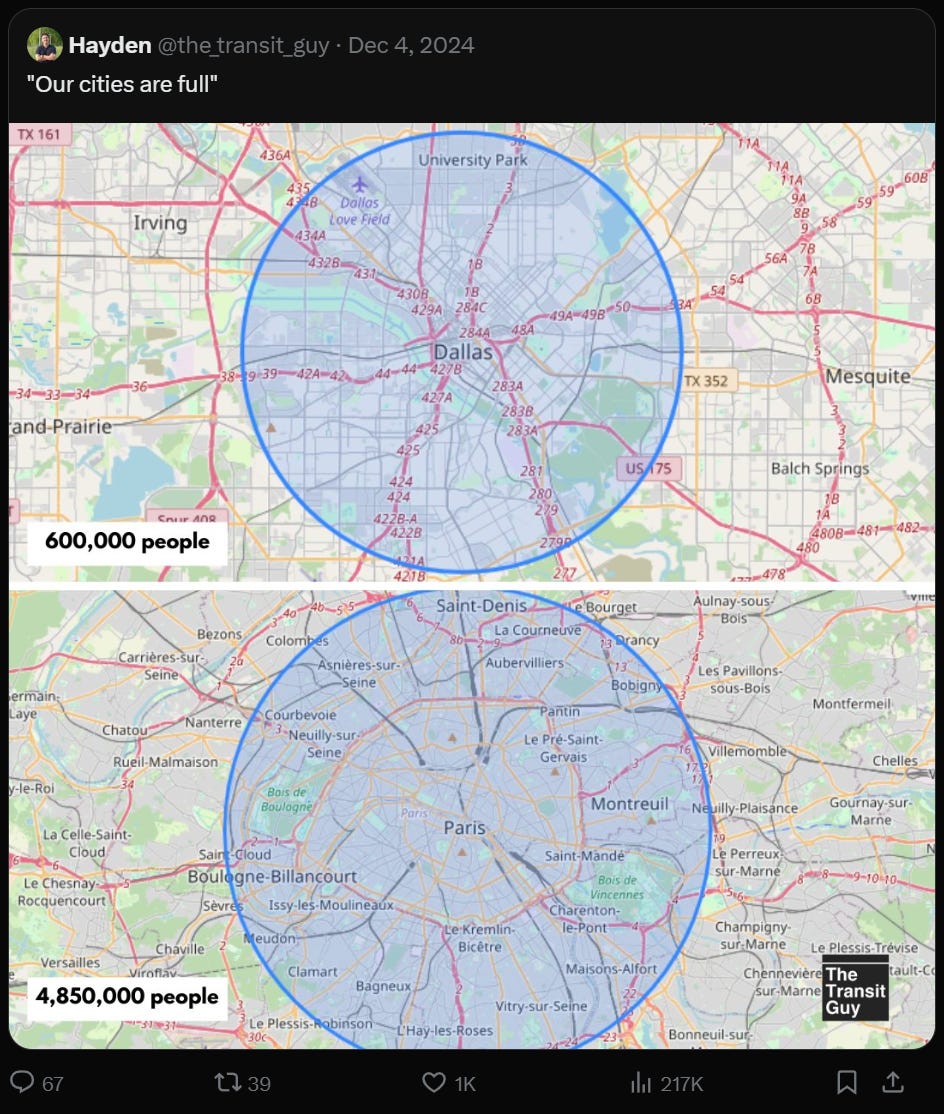

That’s two key things about houses.

They need to be where people want to live.

And they need to enable people to live with the people they want to live with.

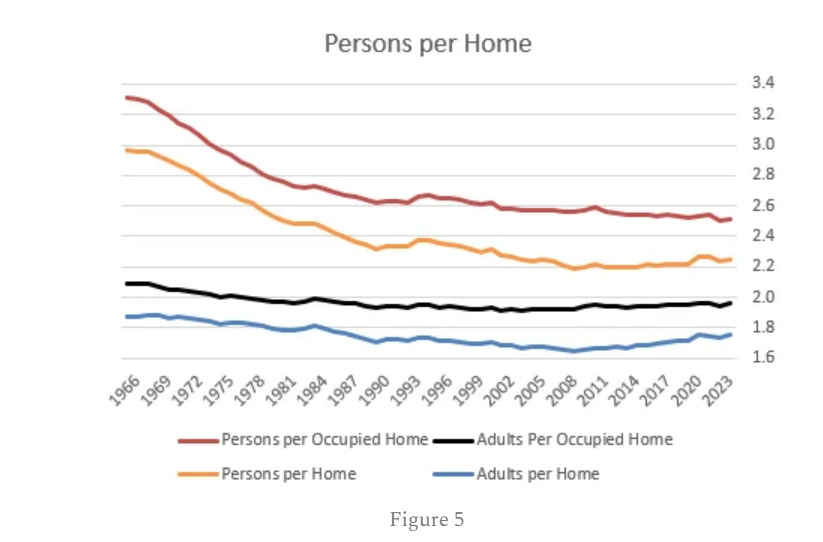

Kevin Erdmann (via Alex Tabarrok) tackles the with whom portion of the problem. We have an all-time high in houses per capita, but we also have less people per household.

I am actually surprised that adults per home has been this stable and this high, given other trends. The drop in children still has to be accounted for.

There is also the issue of where you want to live. If no one wants to live in St. Louis anymore, which is mostly true, then the extra empty houses in St. Louis give people a free option that no one wants, but are limited in their ability to solve our problems.

Scott Sumner points out that the declining number of people per household means we can effectively have a housing shortage even when we have more units supporting fewer people. This is not a huge effect, a 4% decline in household size, but it matters.

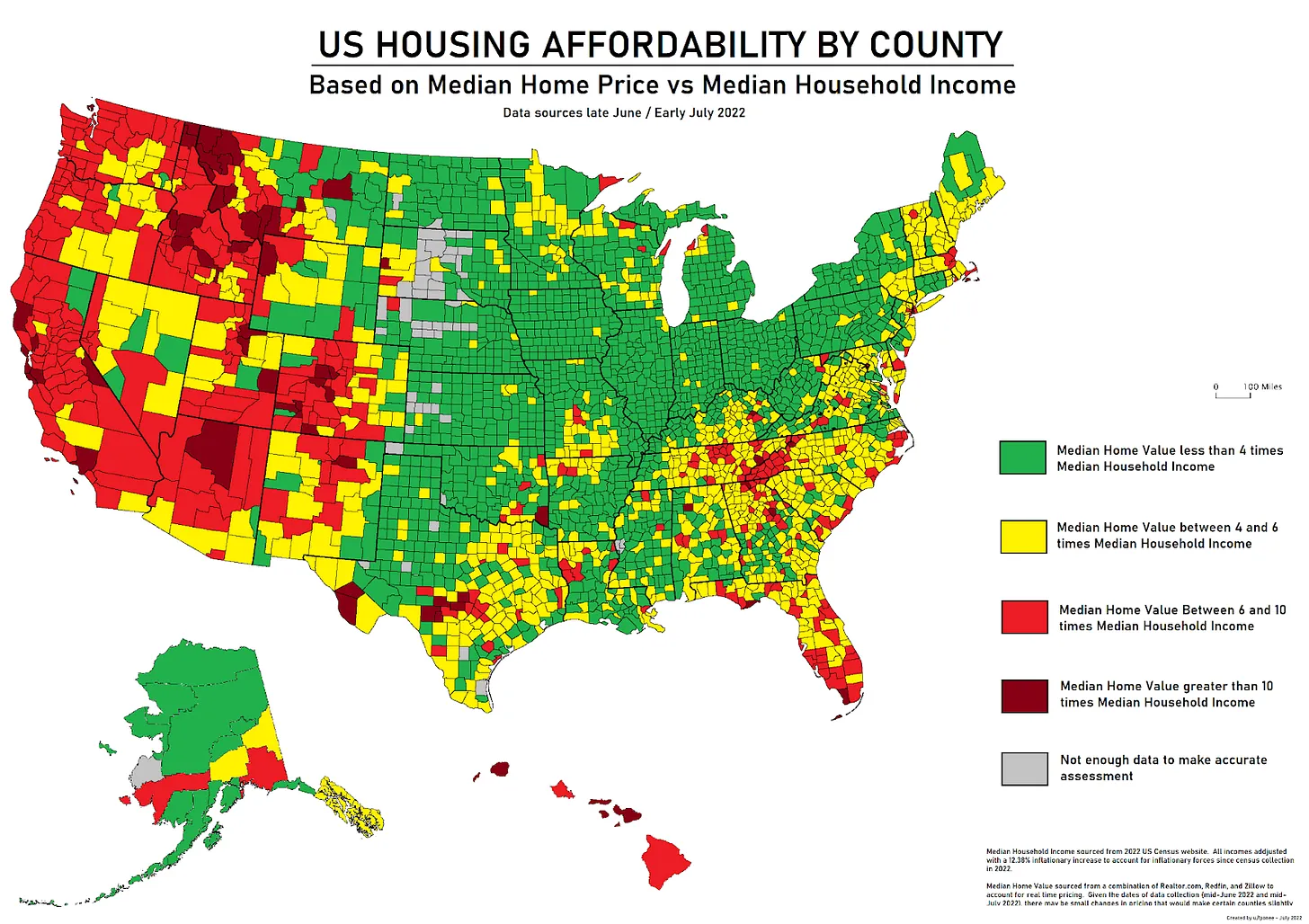

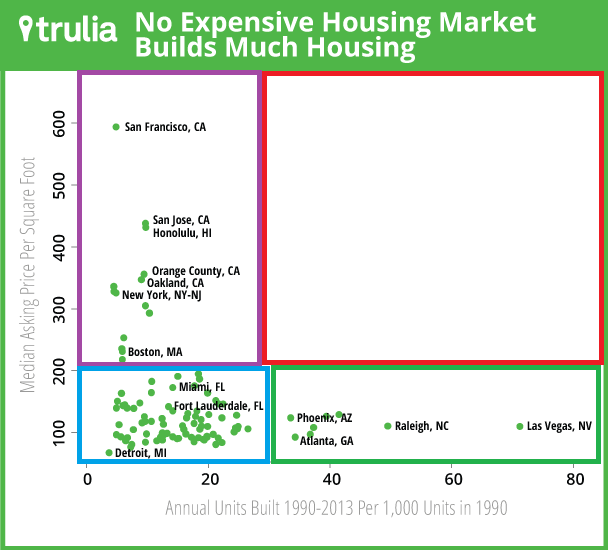

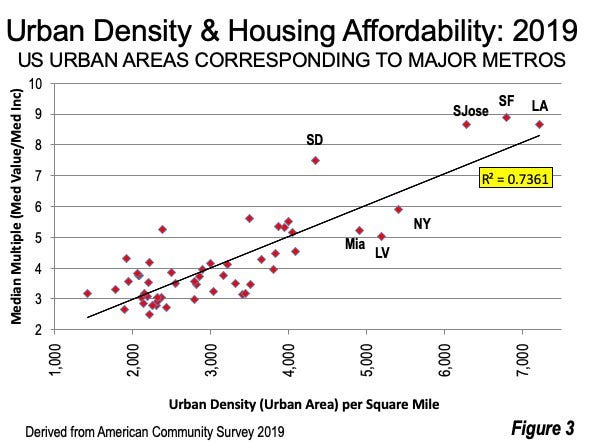

Jeremiah Johnson: The ’empty quadrant’ is one of the most replicated findings in housing research. There expensive cities that don’t build. There are cheap cities that do build. And there are no cities that build lots of housing and still see very high housing costs.

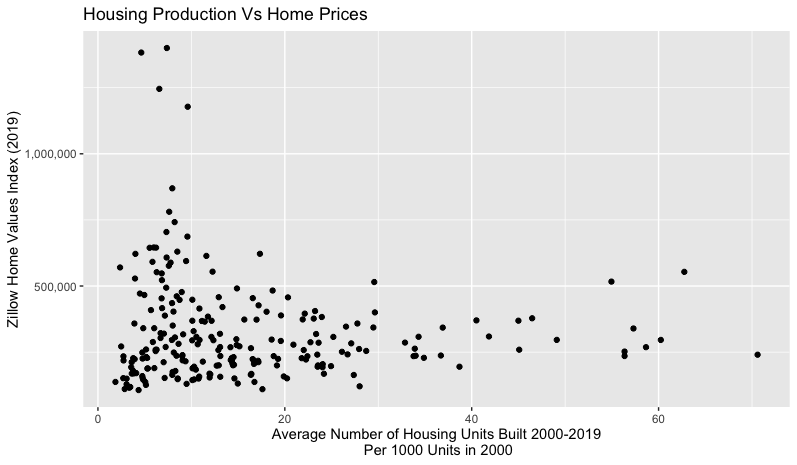

But that chart’s data only goes through 2013, you say! Sure. What if we use a completely different data source and time period? Top right quadrant is still empty.

It works for both overall price level as well as *changesin price level. No city that has large increases in inventory also sees increases in housing cost. Upper right still empty.

Seth Burn: One of the things about new construction that might not seem obvious is that they have an urgent need to fill all of the units ASAP. They start off with debt and need cash flow, so they have to price these units to move. In short, they need to undercut the market.

The counterargument would be that most places have stopped building tons of housing, and the only places that still do so are ones with lots of empty space around and a willingness to grow via sprawl. Those are not going to be high rent locations, so this relationship might not be causal. Except, supply and demand, so of course it also is causal.

Megan McArdle: One of the more interesting paragraphs I’ve read in a while.

Paper: If internet search is increasing equilibrium match quality, then some of the recent observed house price increases may be due to improvements to match quality rather than basic supply and demand factors. Assuming that gross output measures should be adjusted for quality changes, this implies that real growth in the output of housing may be understated due to quality increases being misattributed to the price deflator. Standard hedonic methods for estimating constant-quality price deflators in housing typically only control for the observed physical characteristics of a home, and do not account for unobserved match quality between the buyer and the house.

Megan McArdle: Basically improved search technology might mean people find homes better suited to them, and since they value them more, they might be willing to pay more. So some portion of the house price increases we currently treat as inflation should actually be seen as quality improvement.

So first off, no. Even if true, that is some bullshit, on the conceptual level. That is not what quality means. My being able to find the right house raises the utility I get form my house. It does not improve the quality of the house, and that increase should not impact the deflator. We can talk about matching as another product we produce perhaps, Zillow and StreetEasy count as services, or we can talk about the resulting utility or both, but that doesn’t measure the quality of the housing stock. That is the quality of the matching market.

What about the underlying dynamics? Does better matching increase prices via increased willingness to pay?

This is not obvious. How do people choose how much to spend on housing?

One obvious strategy, that many actually employ, is to buy the best place you can afford. In this case, if matching improves, then one should expect higher consumer surplus, and also for customers to sometimes ‘move down’ and buy a place that is generically worth less because it is better for them. So if anything this would point the other way?

Another obvious and common strategy is to meet your needs, and pay whatever it takes to do that. In that case, better matching will mean you ‘need less house’ to meet your needs. So you will end up paying less, and overall the market should stay static or decline once more.

The standard economic strategy of maximizing consumer surplus, of moving up in price until you aren’t getting enough out of it, could potentially raise overall demand, if better matching meant greater marginal returns not only greater absolute returns.

Then there’s the contrast between houses with multiple matching buyers, where the price gets bid up higher, versus places that are not actually great fits for anyone, so the price collapses. As with many markets, this means that details matter more, and the places that do everything right (the ‘A-level’ real estate) profits, whereas those who are flexible get better deals.

This feels like another one of those ways in which economists tell people they are better off and getting richer, and people look at them like they are crazy.

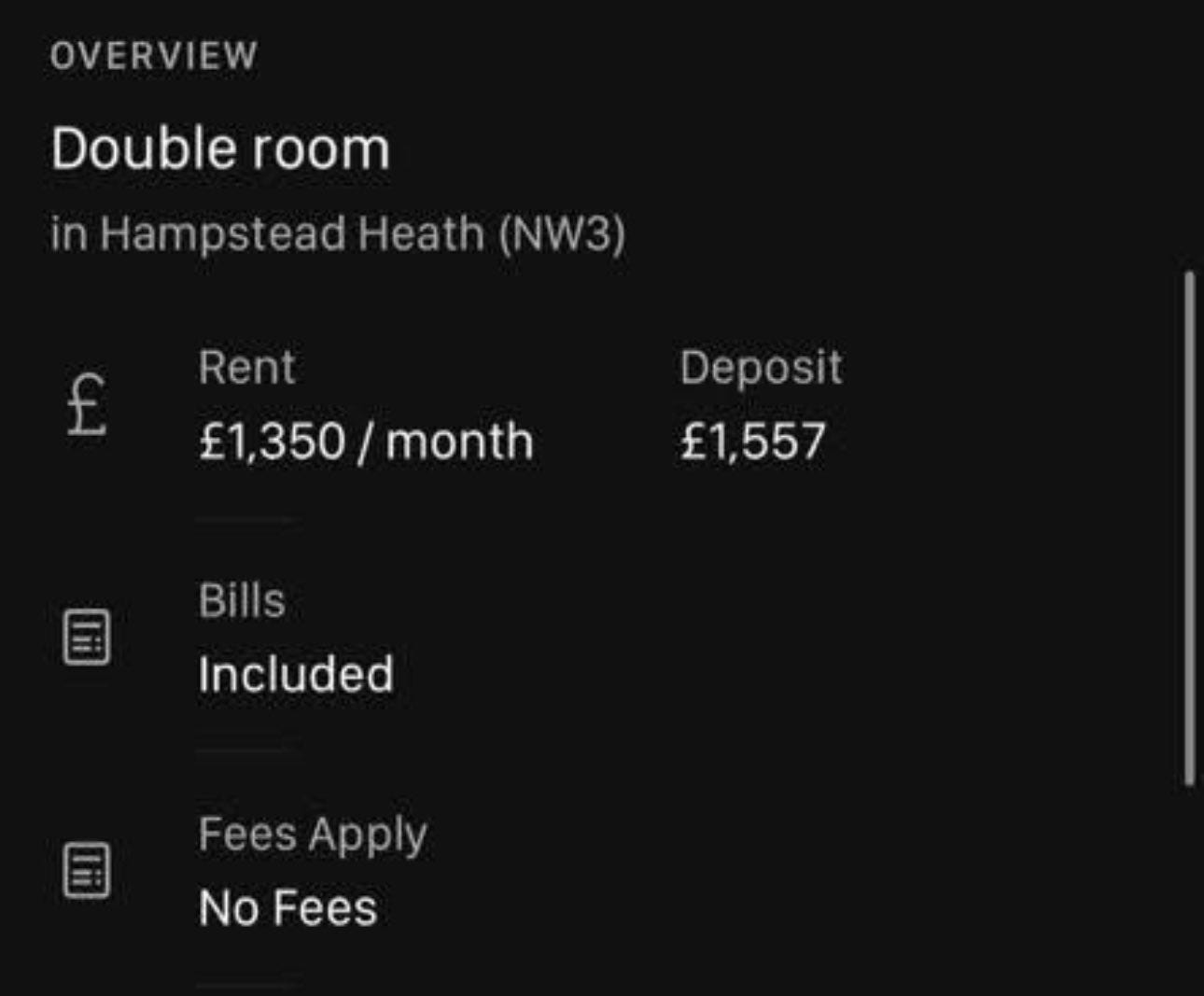

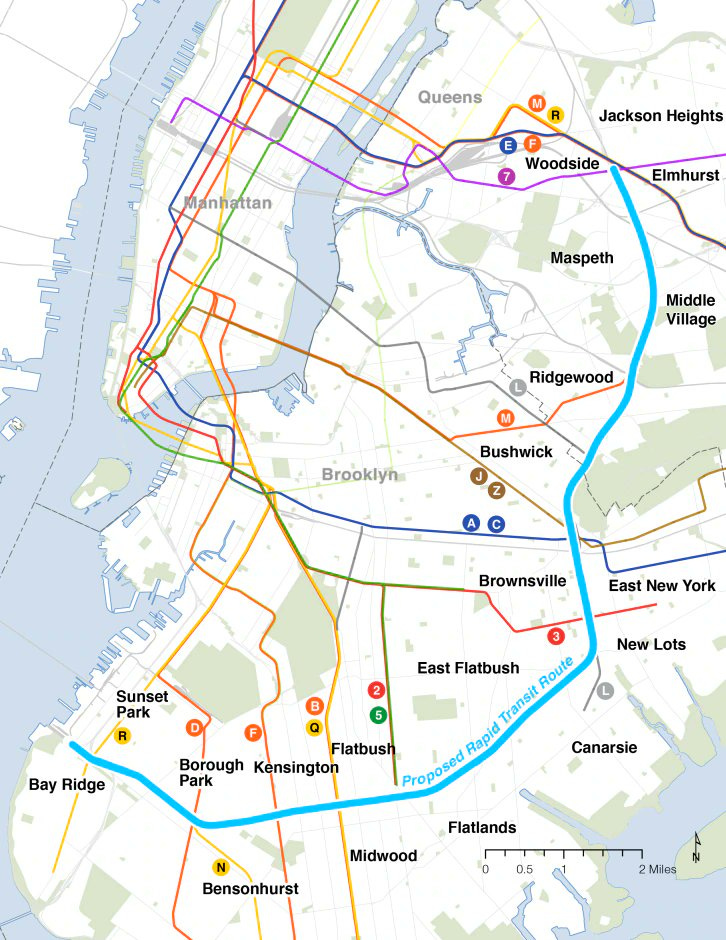

Why do I want Balsa to help us intervene in housing at the national level, rather than the local and state levels where all the action has been so far? Because if you act everywhere at once, then everyone knows they are not the target, that their particular neighborhood will probably not much change in relative terms, and they can accept the deal.

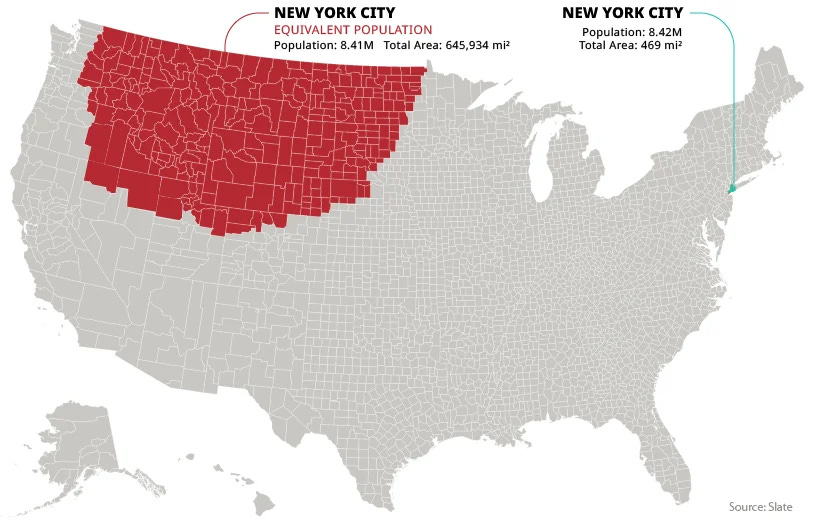

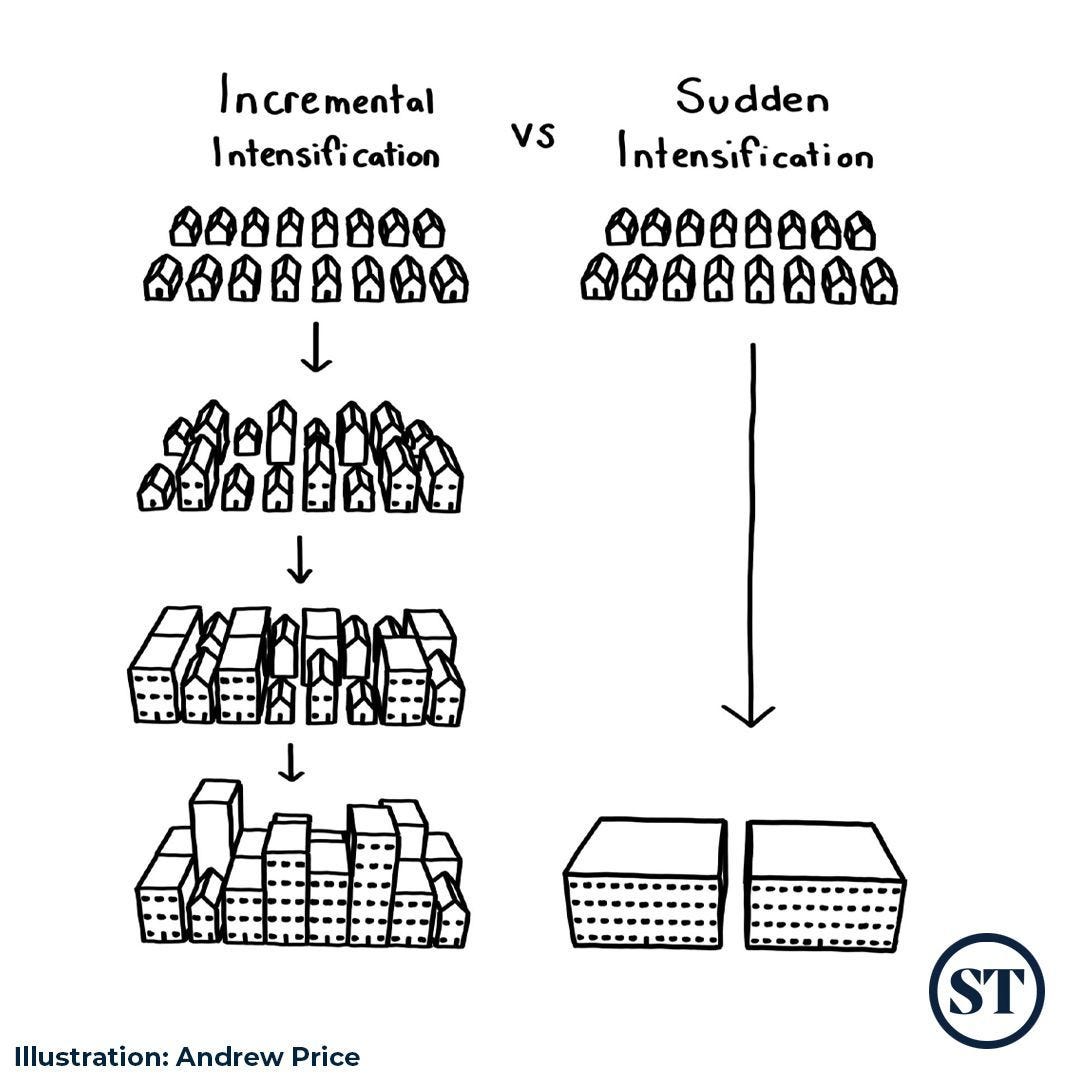

Kevin Erdmann: The irony of the immediate yimby project is that the solution – that we need to legalize and build 10-20 million extra housing units – sounds outrageous. And yet, if those units were equally distributed across every city, would be barely noticeable in the built environment.

Matthew Yglesias: This is exactly right — dramatically reducing land use regulation in your neighborhood would be very disruptive but doing it in *everyneighborhood (including yours) would transform the national economy without changing that much in any specific place.

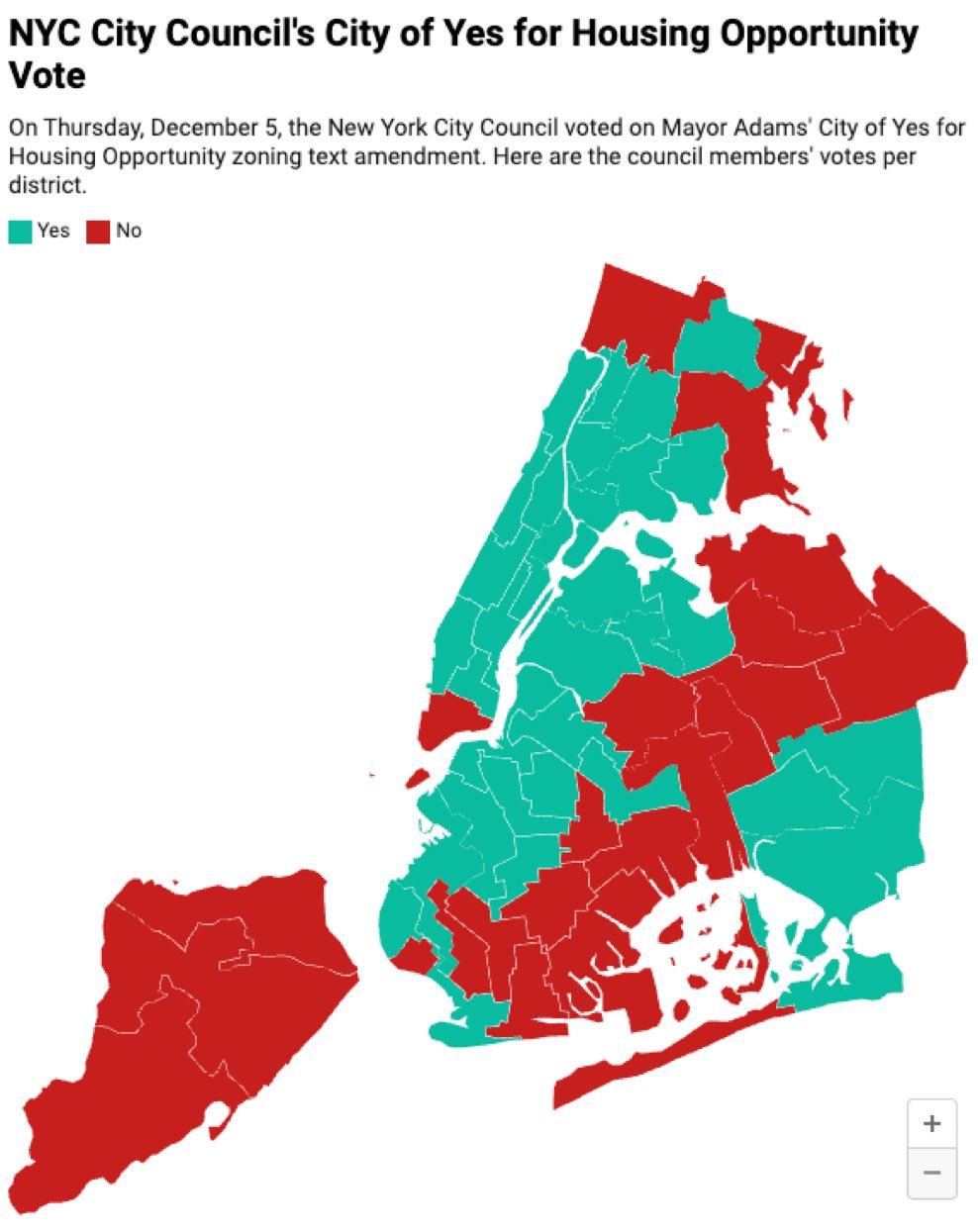

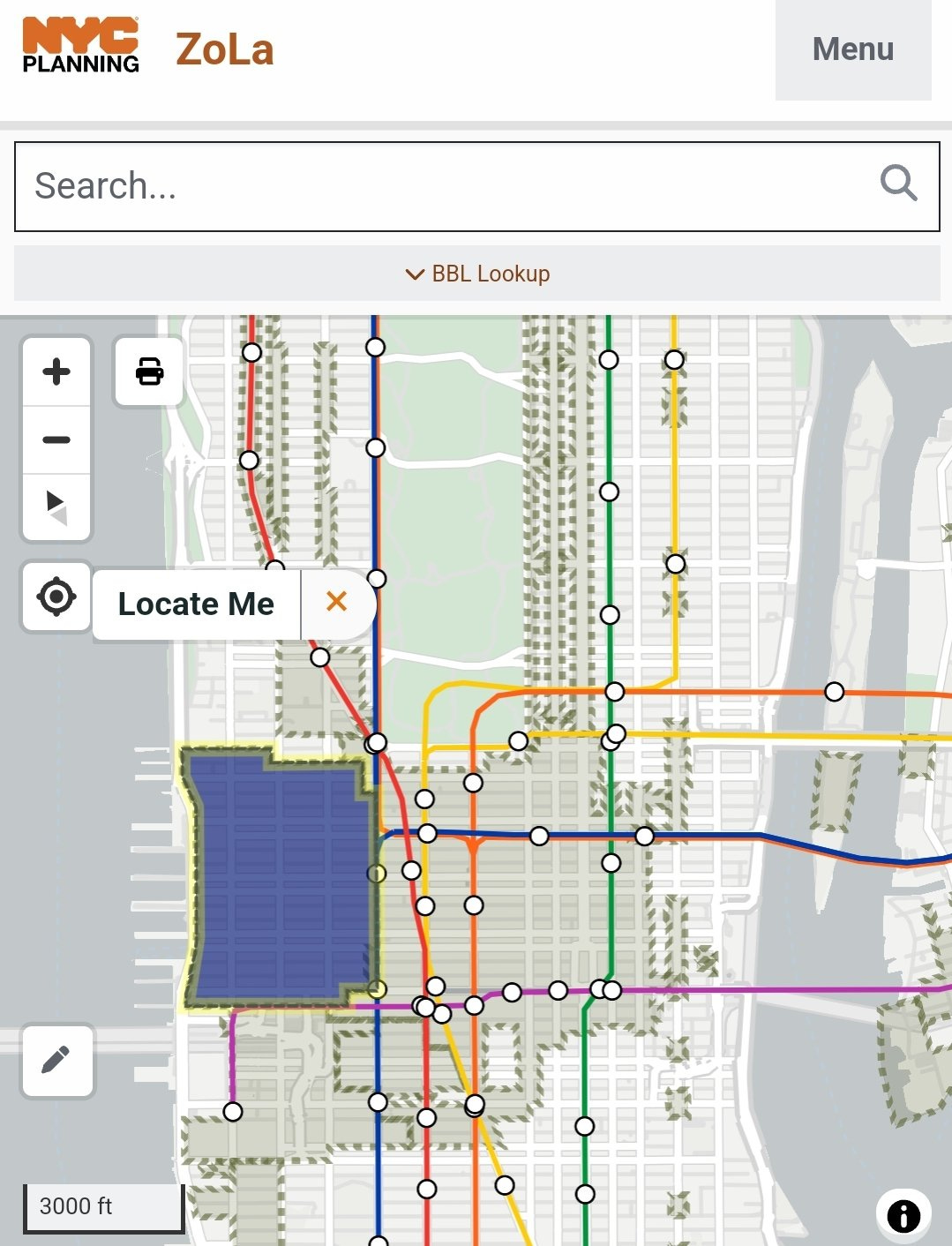

We still should change certain specific places quite a lot. The most valuable cities, especially New York City and San Francisco, should grow much bigger. And there are some hugely underbuilt other areas like Palo Alto. But mostly this is a deal that should have overwhelming support, if done all at once.

Here’s some rhetoric that I presume is not helpful, although obviously true:

Matthew Yglesias: YIMBYism makes leftists insane because “it should legal to build apartment buildings where there is demand” is obviously correct, but they also don’t want to admit that a significant social problem could be ameliorated with less regulation.

If you own a home, you own two things.

-

The home.

-

The land.

When zoning changes, you get to build on your own land too, or sell it someone who will. It is not crazy to think that the land might go up more than the home goes down.

Alas, this does not seem to be the case.

Harlo Pippenger: If you’re a YIMBY and homeowner, do you believe you’re supporting policies that will cause you to forgo thousands in home equity?

Matthew Yglesias: My view is that better regulatory policies will increase the value of land but decrease the price of housing.

Buildhomez: I don’t think so based on Houston.

The study says it did not happen in Houston, perhaps because so much new housing was built that this was sufficient to offset the value of being able to build.

Ben Southwood here walks through the obvious fact that if all the homeowners of Palo Alto got together to turn it into the density of lower Manhattan, they would come out massively ahead, creating by his estimate $30 million in profits per household. So, he says, NIMBY is not about money and home values. Alas, that does not follow, because homeowners are not thinking this way and considering this alternative, merely opposing each marginal change in turn.

It does however propose an alternative. We are talking about $1 trillion in total net profits, to be divided between landowners and developers, and a total investment required on the order of $2 trillion to get it including upgrading city services including mass transit.

So the obvious thing to do is to run for mayor with a city counsel slate, on a platform of full Manhattanization, and an offer as part of that to buy all existing homes for their current assessed value plus $5 million. Get funding from every VC in the Bay, stop thinking so small. Sure, some people would still vote no, but would half of them turn that down? Plenty of other places to buy elsewhere with your windfall, if you want to keep the old lifestyle going.

Space can definitely be oversupplied where people less often want to live. Once it starts, it makes the problem worse.

Unusual Whales: Oh, no.

The largest office building in St. Louis has sold for $3.5 million, per WSJ.

In 2006, it sold for $205 million.

Konrad Putzier (WSJ): “It’s a classic chicken and egg kind of deal,” said Glenn MacDonald, a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis’s Olin Business School. “People don’t go there because there’s nothing to do. There’s nothing to do because people don’t go there.”

…

From there, desolation spread south. Across the street from the garage, a St. Louis Bread sandwich shop—part of the Panera chain—shuttered. That left the attorneys at law firm Brown & Crouppen without a lunch spot.

“It’s pathetic that a Panera was the thing holding this area together, but it really did,” said the firm’s managing partner Andy Crouppen. “It brought people from five, six blocks away, it created a little bit of activity.”

“When that left, it created a noticeable void in the area,” Crouppen said. “People started walking in another direction.”

This is the 44-story AT&T tower, so I presume it is the building on the left. The majority of area storefronts sit empty.

Several replies claimed this failed to include assumed debt, but there does not seem to be debt? According to Wolf Street, this same building was sold for $4.1 million in a foreclosure sale in 2022, which means it was bought debt-free. It also means this was a loss even from that low point.

Danielle Fong: imagine you just bought this. what would you do with it?

Benjamin: there is a crazy power incentive that came with this, something like <7c/kw hr I think.

Obviously at that point turn the whole thing into a btc mining farm.

The obvious play is to convert a lot of this to housing plus commercial space, while leaving some offices for those same people.

Indeed, one could imagine building one hell of an intentional community and world community hub with this much space. And there would then be plenty of space to include what would effectively be a convention hall on a few floors, and other public areas. I imagine one could get really creative, if the law allowed it.

But the regulatory issues and costs of conversions have defeated many who have tried in St. Louis already, and I am assuming anything like this would be a giant mess.

And of course, the $3.3 million is almost exactly $0, when compared to the cost of upkeep. Claude estimates that cost at between $5.6 million and $8.7 million per year, including property tax of 3% on the new value of $3.5 million, although you would get some discount on that if the building was largely unoccupied. So in a sense the ‘cost to own’ in a practical sense here is on the order of $100 million, or about $2 million per floor or just under $100 a square foot.

I am actually rather excited by what you could do with a building like this at a price like that, assuming it was in good physical condition, and especially if you had the budget to make supplementary investments in the area. You could think big, and ensure that the area suddenly had good versions of everything people actually want to have locally available, by being willing to initially run them at a loss, including inside the building.

Why is this building worth something rather than nothing? The price is an option. If you buy the building for $3.5 million, you always have the option to sell it for $0, as indeed effectively happened in 2022, since transaction costs ate the entire sale price. If you figure out how to make the building profitable, or St. Louis gets a downtown revitalization and suddenly people want to come back, you win big. So that is worth something, even if you then must pay millions a year if you want to hold onto it. Alternatively, it is pure winner’s curse. The option value is not worth the ongoing costs, but someone will be willing to try.

My guess is that the bet is good if you can afford to make the full bet and lose, considering the upside. But if you have this kind of budget, risk appetite and willingness to actually do physical things, then you have many great opportunities.

More surprising is this sale, given that Washington D.C. is going well. It looks like it was due to massive floating rate debt, and in this case all we actually know is that no one thought it was worth assumption of the debt?

Triple Net Investor: JUST IN: Holiday Inn Express in Washington DC sells at a shocking ~80% ‘discount’ to debt owed.

The lender was the only bidder in the foreclosure auction, bidding $18.5M.

The lender was owed $83M as the largest secured creditor.

The 247 room hotel opened in Dec 2022.

And here we have 1740 Broadway in New York selling for $185 million, down from $605 million, it is approximately 600,000 square feet. So tempting. This resulted in the first loss on an AAA-rated slice of a CMBS deal since 2008.

And here is 750 Lexington, down from ~$300 million to about $50 million.

Here’s San Francisco’s 995 Market Street, sold at auction for $6.5 million versus an old price of $62 million in 2018:

Boston flirts with doom loop territory.

Brooke Sutherland and Sri Taylor (Bloomberg): Boston Mayor Michelle Wu is seeking to raise commercial property tax rates to help protect homeowners from the brunt of the historic slump in office property values.

So your commercial real estate drops in value and your response is to tax it more?

This seems like it shouldn’t be sustainable?

This is less extreme, but similar.

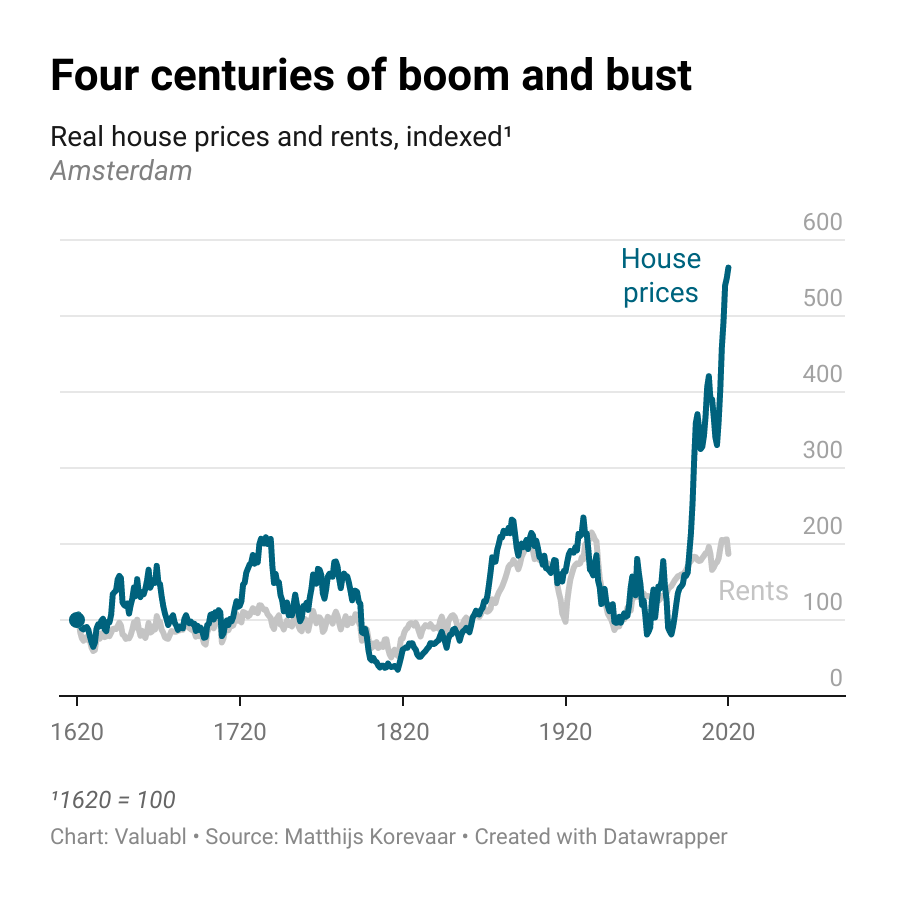

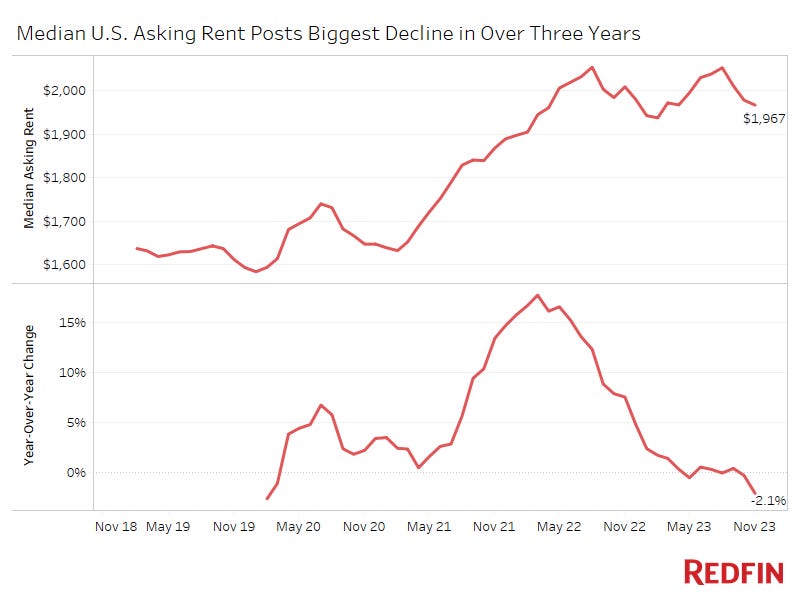

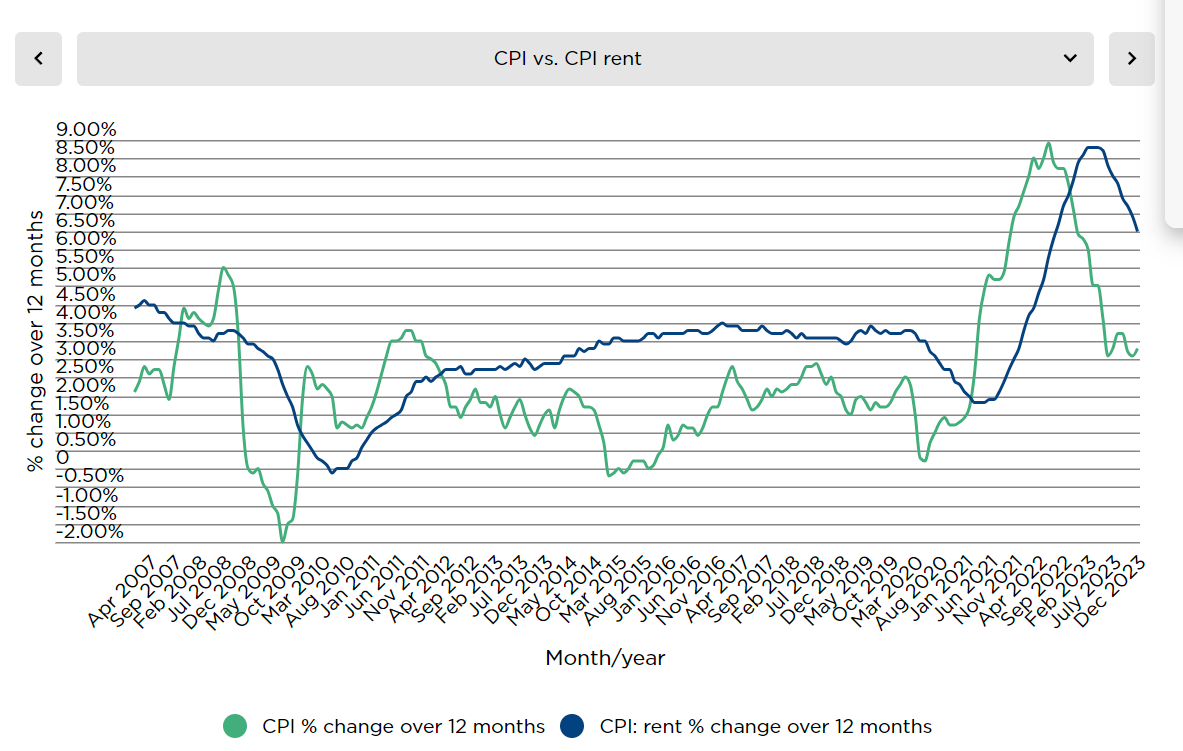

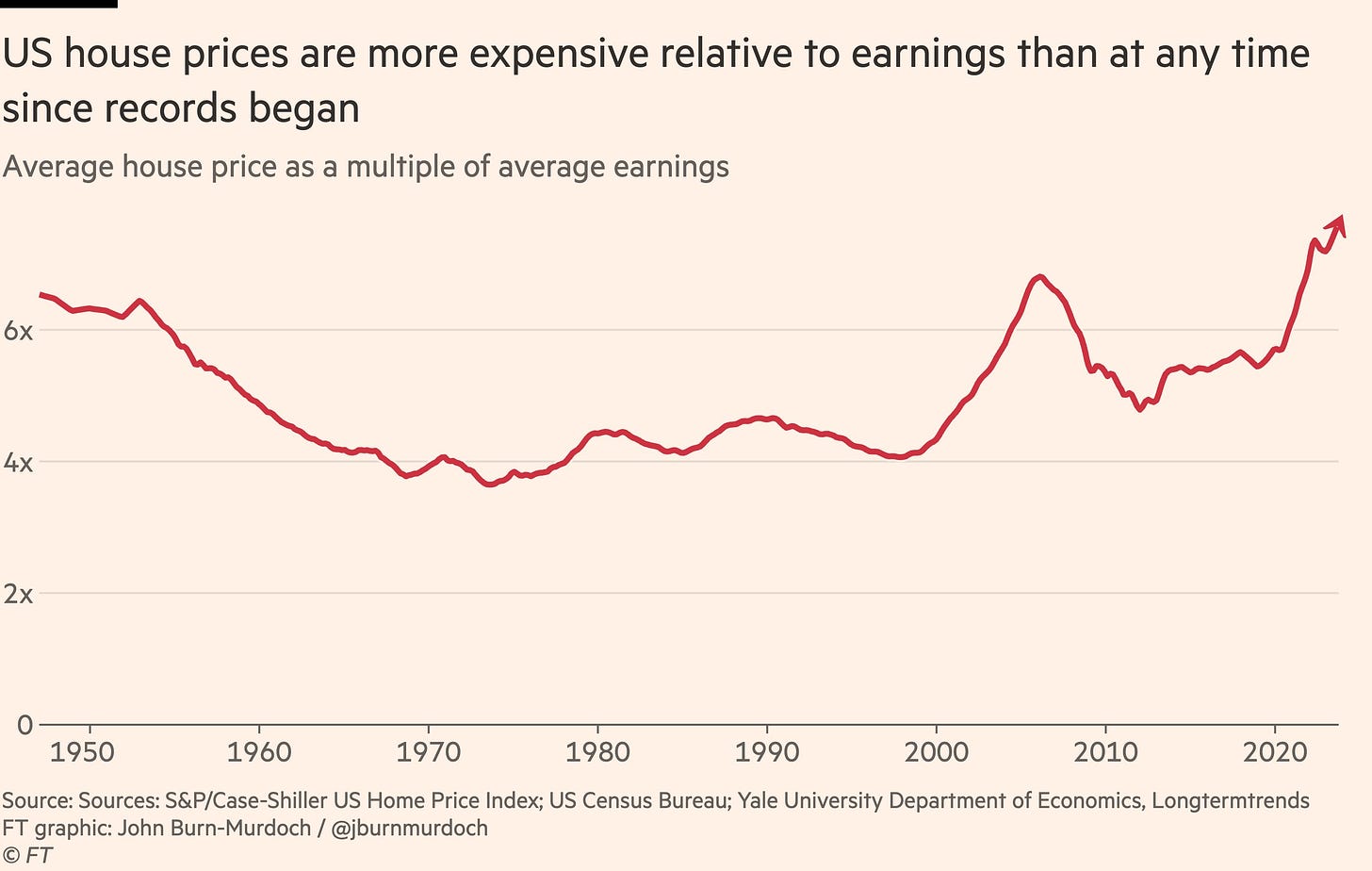

It is especially baffling given the recent jump in interest rates. With a 3% fixed rate mortgage, sure, a 140 ratio is not so crazy. At 7.22%, it seems pretty crazy. After other costs of ownership, that makes ownership very clearly unprofitable versus renting. In general, why does the rent-to-price ratio change so little when interest rates move?

Tomes Pueyo also notes that population has previously been going up. Soon it will begin going down, as it already started doing in China. Declining demand follows. He has a bunch of other speculations as well.

What if the ‘superstar cities’ like New York and San Francisco are not superstars after all, and merely ‘closed access’ cities? Kevin Erdmann makes that case. Their rents and productivity numbers are only high, he says, because they prevent housing construction and choke off supply. Yes rents are high, but also they fully capture the gains in income, if you include that they price less productive people out of living there. He says we shouldn’t see such cities as having such high demand, and contrasts this with Detroit’s heyday, when it was more productive but only modestly so because it did not keep people out.

I don’t buy this at all. Yes, it is sad for you if you move to New York, your productivity doubles, your salary doubles and after rent and taxes and other higher expenses you do not have any more money. That does not mean your productivity did not double. Even if you are doing the same tasks, the fact that people willingly pay you twice as much is strong evidence that your production is worth more.

Also, price will always be the ultimate measure of demand. So when he says ‘it isn’t remotely clear that demand for living in Los Angeles is higher than Dallas’ (really Dallas-Fort Worth) because Dallas-Fort Worth grew by 77% from 1995 to 2022 (it seems like Dallas itself only grew about 30%?) while LA only grew by 10%, again, look at prices and population.

Or ask people where they would live if the economics was similar. Yes some people will prefer Dallas for political or social reasons, or because of particular people there, but obviously most people would, if given the choice where money canceled out, rather live in Los Angeles, or in the version of Los Angeles that was growing faster.

He also highlights other trends, and especially points to house prices dramatically declining in poor areas of cities like Atlanta due to inability to get mortgages in the wake of the financial crisis and the subsequent tightening of lending standards. This seems to now be fully reversed, but the inability to get mortgages remains, forcing people to rent, and the lack of interim building forced rents up. Well, then, that sounds like a problem that should fix itself in turns of rental stock. In terms of mortgages, that is a policy choice.

But as always, if someone is saying no one can afford to buy a house, one can respond that the homeownership rate is up rather than down. So that’s weird.

A flashback I continue to not understand:

Zvi Mowshowitz (October 10, 2022): A remarkably high share of the responses to ‘why is it illegal to have a bedroom without a window?’ seem to be willing to bite the bullet that it should be illegal for me to have the blinds down and the window closed.

Ja3k: Wow, I had no idea. I almost think a bedroom with no windows would be desirable as I only use the room for sleep and tend to expend a lot of effort preventing light from coming through the window

Zvi Mowshowitz: Yeah, that’s the funny part in all this, if everyone was like me we’d make sure all the windows were in the common areas and the bedrooms were always dark.

And now:

KUT Austin: “Windows should be a human right,” said Juan Miró, an architecture professor at UT Austin who has advocated against windowless bedrooms.

Headline: Austin outlaws the construction of windowless bedrooms.

St. Rev Dr. Rev: Imagine the society we could build when the upper middle class forces even more of their preferences and consumption habits on the rest of us in increasingly ridiculous and unsustainable ways.

Luis Guilherme: Building windows wouldn’t be hard if fire codes didn’t require more than one staircase. Both together severely limit what you can build.

Tracing Woods: This is a petty case, but I’m always fascinated by those who use the language of human rights to remove them. “I want to ban people from building things I dislike” becomes, with the wave of a hand, “My preference should be a human right.”

Neat trick if you can manage it.

Dan Elton: Some problems with windows in the bedroom:

– More noise

– Harder to maintain consistent temperature for sleep

– Higher heating/cooling costs

– Need to install blackout curtains (extra cost, need to be maintained).

(Otherwise light trickles in from moon, street lamps, etc)

The first thing a large percentage of people I know do when they move into a bedroom is to do all they can to functionally destroy the window.

As a reminder, no this is not about real safety. Many such bedroom windows offer no meaningful means of egress or entry.

I continue to see this as obviously and exactly backwards. Windows in a bedroom are a mixed blessing at best. Yes, you get a reminder of when it is light or dark outside, but in exchange that interferes with your sleep. Not ideal, my blinds are down most of the time and I paid a lot to effectively get rid of my giant window most of the time. Whereas windows in living areas are obvious goods, and of much higher value.

So my preference order would be:

-

No requirements because people Capitalism Solves This. If people want windows people will pay more for windows and we will get the right number of windows. Banning what you dislike is the opposite of a ‘right.’

-

Require a window somewhere in the apartment, on the theory that ‘windows are a human right’ or the worry that people will feel pressured into moving into windowless places and go insane. I disapprove, but I do get it.

-

Require a window in the living area.

-

Require a window in the bedroom area.

A tour of a fully minimalist 250 square foot bachelor apartment in Tokyo for $300/month. Ten minute walk from the train station, has all the basic things for a base of operations, completely illegal to build basically anywhere in America you would want to build it. This seems pretty great, we should do a lot of this. Yes, it sucks to be this cramped, but letting people conserve capital and have a good location is really important.

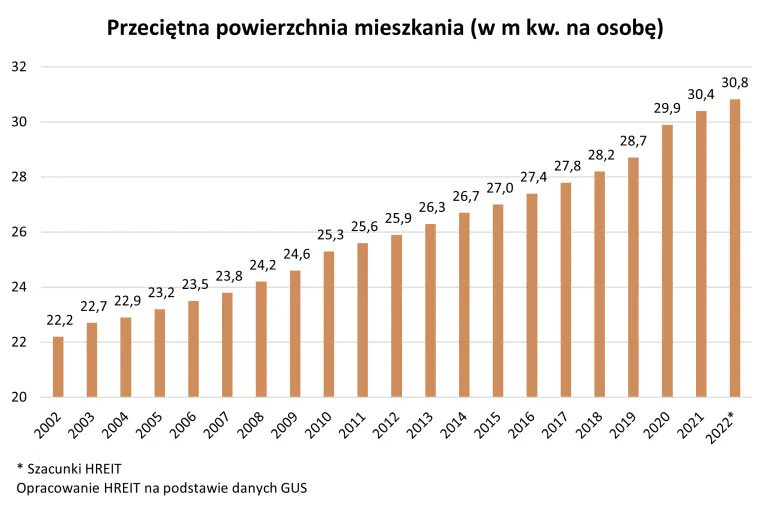

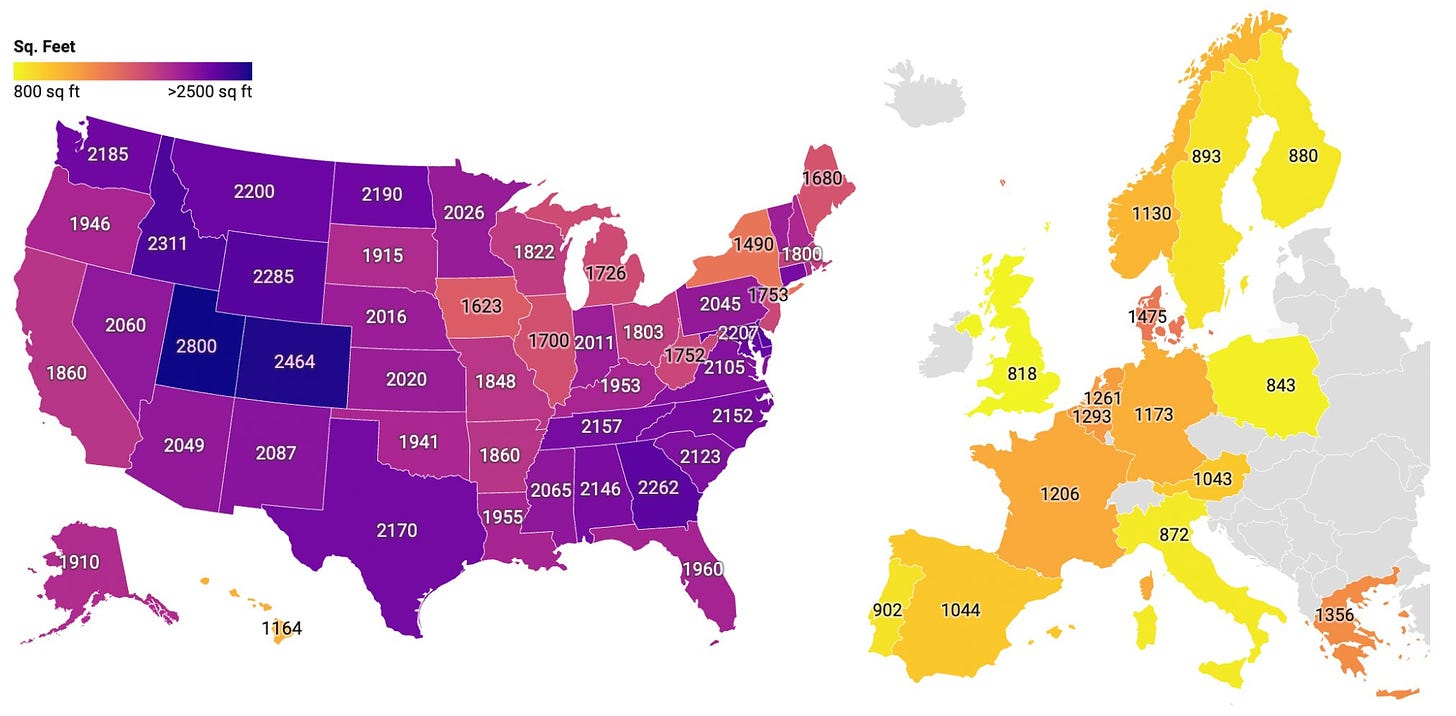

In America, on the other hand, we go big when we go home.

Matthew Yglesias: Not only are European homes small, twenty percent of the square footage is occupied by clothes hanging up to dry.

But they have more orderly public spaces!

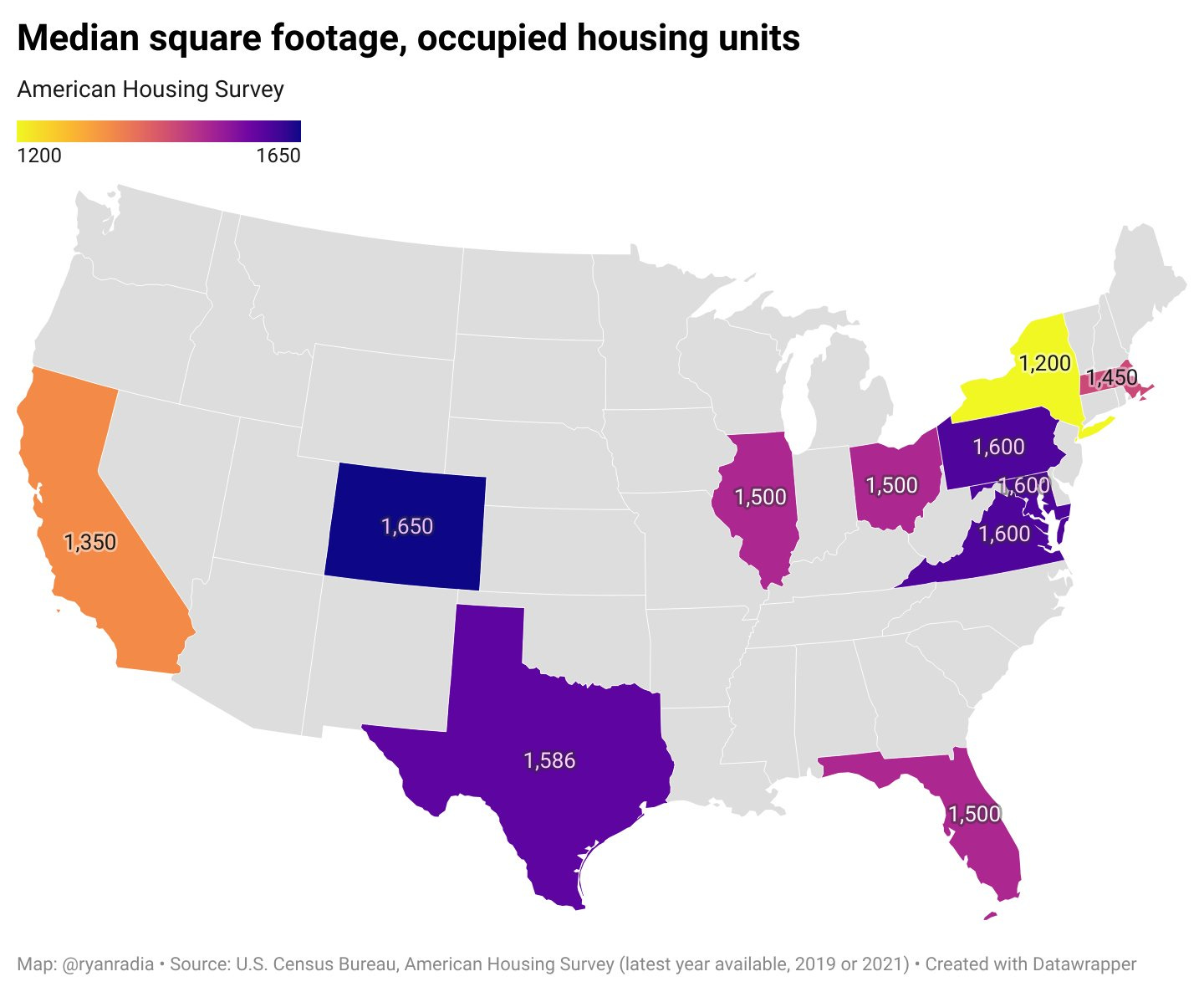

Ryan Radia: Maybe the American Home Shield® analysis of Zillow data is more accurate than the HUD-Census Bureau American Housing Survey, but for those who are curious about the latter, it tends to show somewhat smaller housing units in the United States (only certain states are available).

Looks like American Home Shield includes houses and condos, whereas the American Housing Survey includes houses, condos, and apartments.

[first graph below is Zillow, then the one below is HUD]

You know who goes small and stays home if they have one? The UK.

Yes, I am going to go out on a limb and say that having tiny houses in general is bad. Having more house is good.

The counterargument is that having smaller dwellings is good for the UK in the sense that the amount of housing seems permanently fixed. So if you only have so much space, you need to divide it into smaller locations, or you’ll be even more short on housing than you already are.

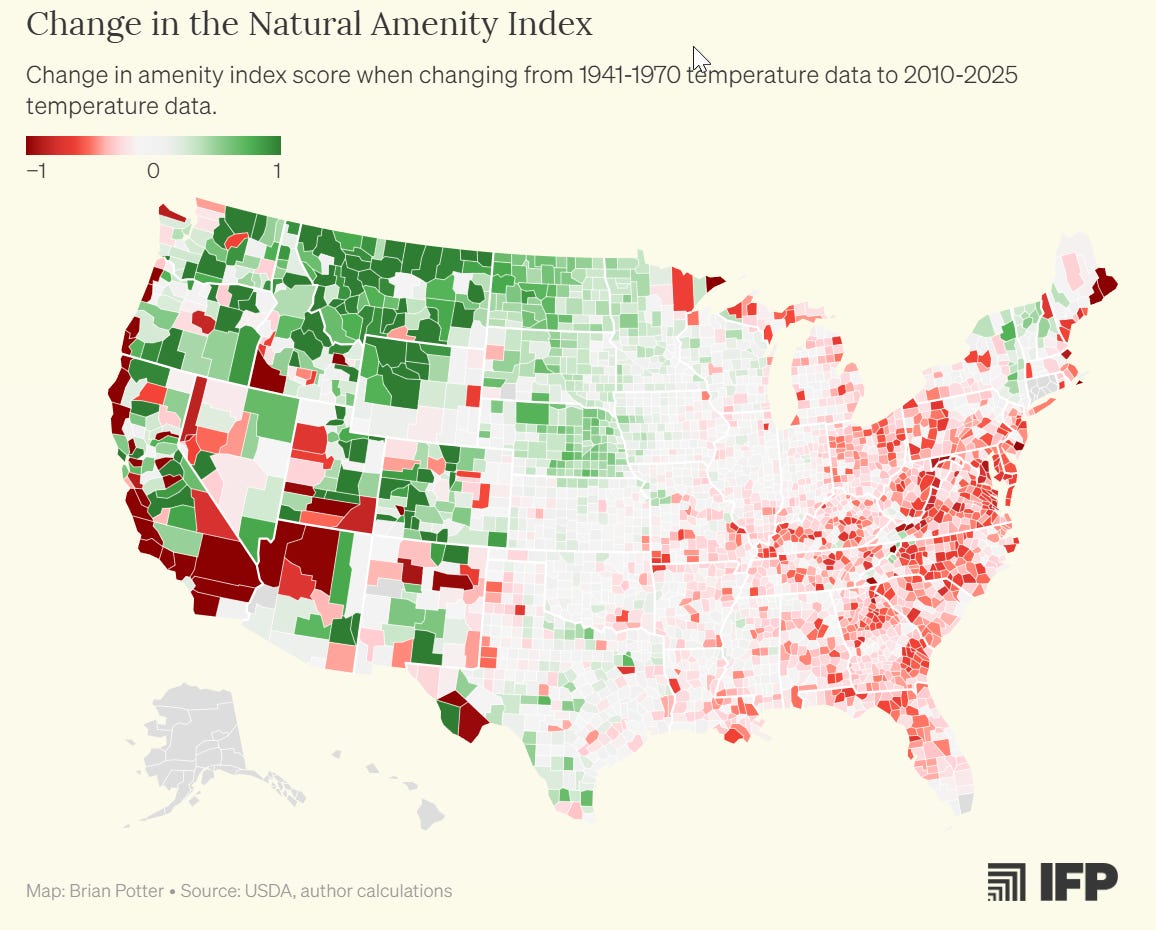

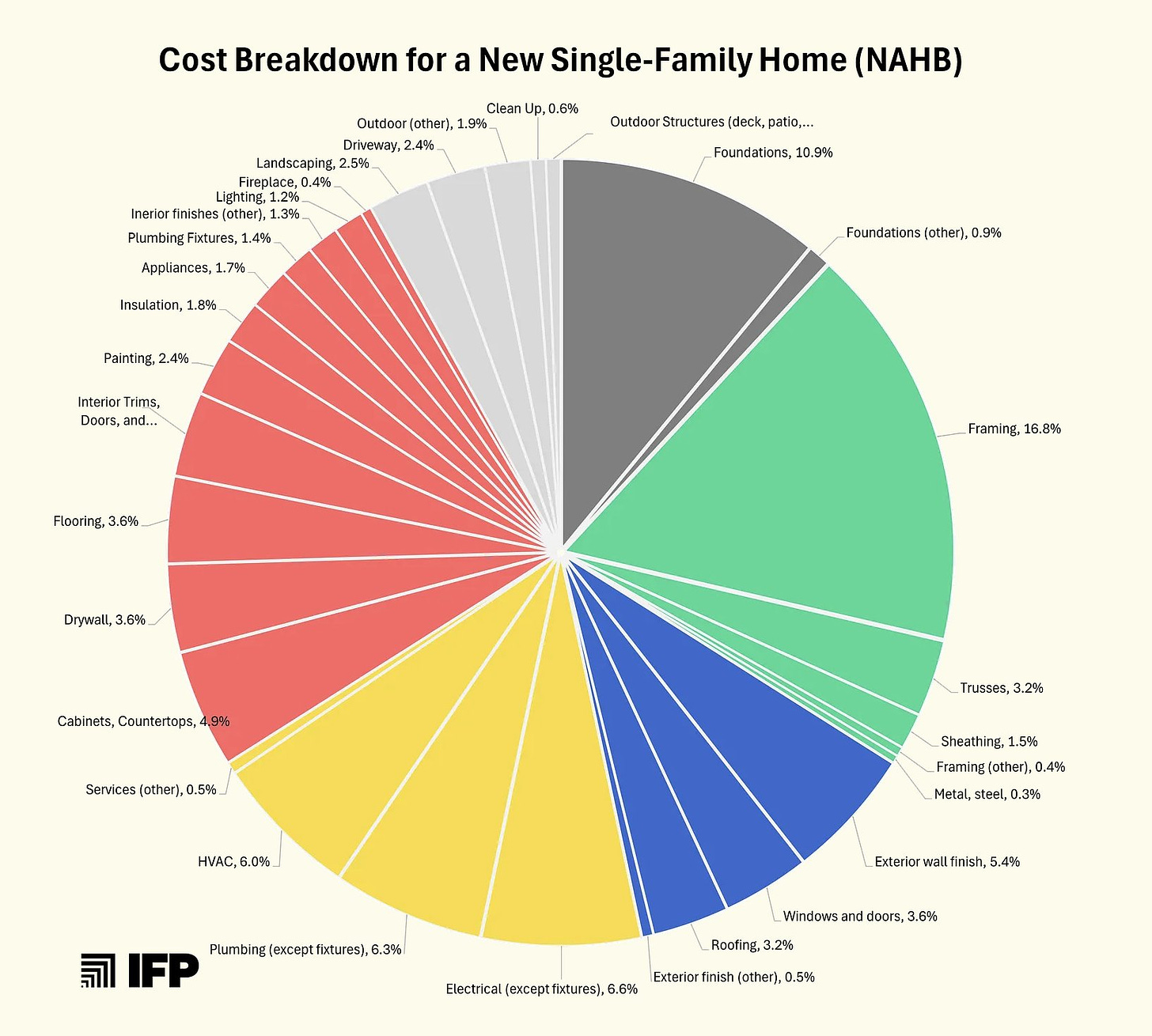

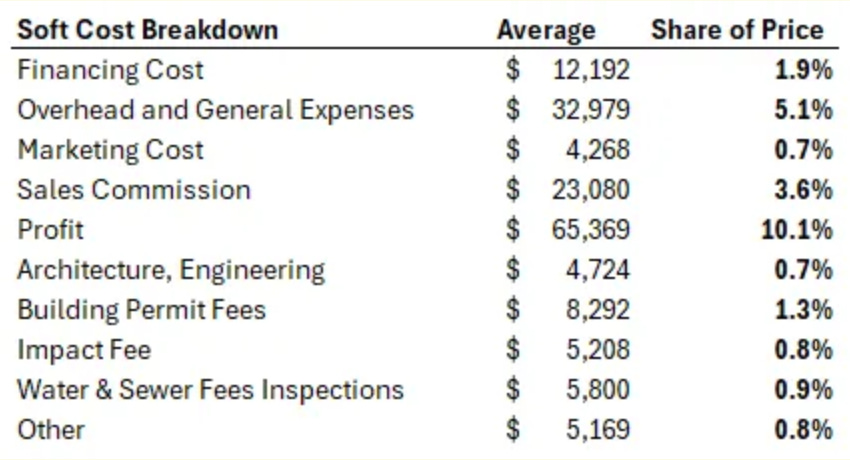

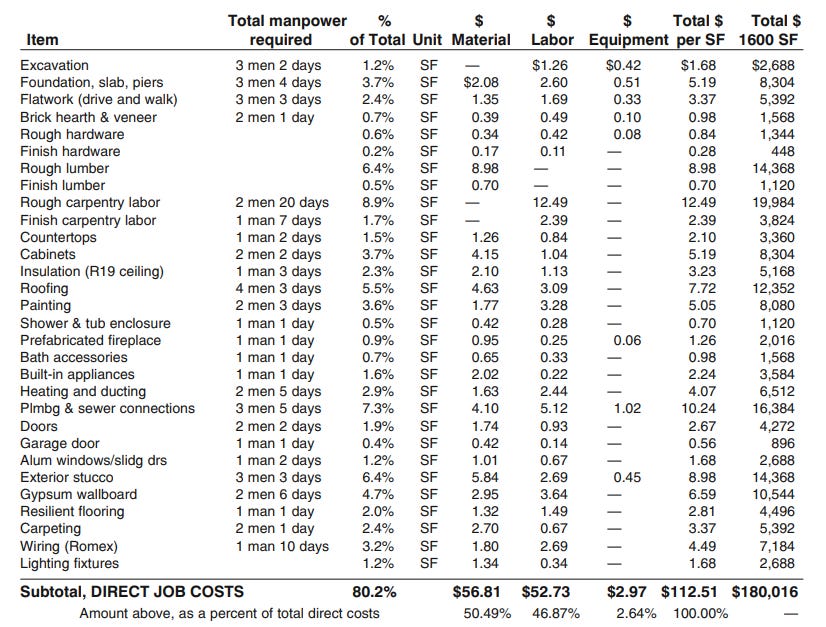

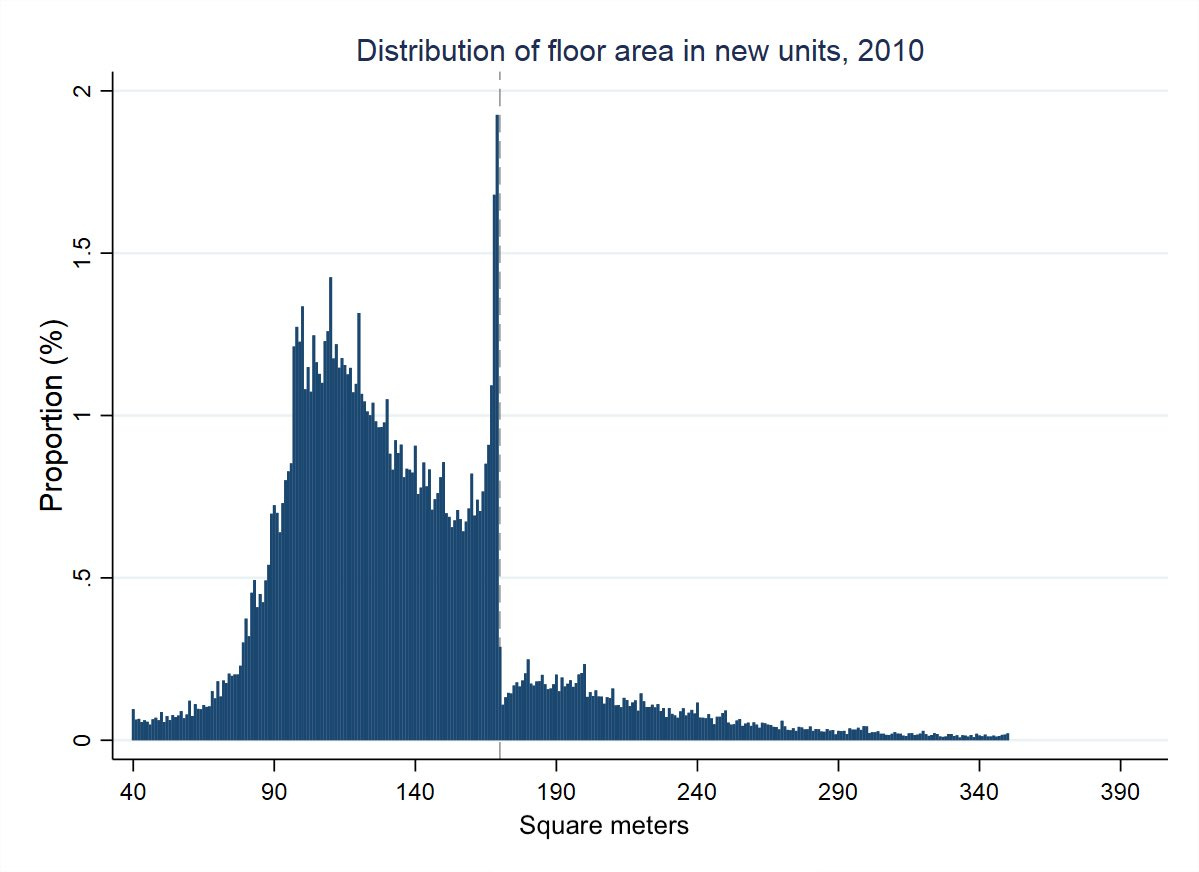

This is a cool chart, from What Makes Housing So Expensive? by Brain Potter.

This is the ‘hard’ costs:

Brian Potter: The above graph is color-coded: green is the structural framing, blue is exterior finishes (including doors and windows), orange is services (electrical, HVAC, etc.), red is interior finishes and appliances, dark gray is foundations and light gray is outdoor work and landscaping. And if we look at a similar breakdown of tasks given by the Craftsman Construction Estimator, we see a broadly similar division.

The most striking thing here is that there is no one striking thing. Construction costs are lots of different little things, not one big thing.

Also note that this excludes the direct costs of dealing with regulations and zoning and approvals and permits and such, and also the cost of the land. Here are some additional costs:

And a further breakdown of some of the hard costs:

Brian Potter: Per the NAHB, on average hard costs are about 56% of the total costs, soft costs (including builder profits) are about 25%, and land costs are about 18%.

…

We see that hard costs are roughly 50/50 split between materials and labor (and we saw something similar when we looked at how the cost of individual construction tasks has changed over time).

Stephen Smith has an editorial in the New York Times discussing the absurdity that is the cost of and rules around elevators in America.

Stephen Smith: Elevators in North America have become over-engineered, bespoke, handcrafted and expensive pieces of equipment that are unaffordable in all the places where they are most needed. Special interests here have run wild with an outdated, inefficient, overregulated system. Accessibility rules miss the forest for the trees. Our broken immigration system cannot supply the labor that the construction industry desperately needs. Regulators distrust global best practices and our construction rules are so heavily oriented toward single-family housing that we’ve forgotten the basics of how a city should work.

…

Nobody is marveling at American elevators anymore. With around one million of them, the United States is tied for total installed devices with Italy and Spain.

…

Behind the dearth of elevators in the country that birthed the skyscraper are eye-watering costs. A basic four-stop elevator costs about $158,000 in New York City, compared with about $36,000 in Switzerland. A six-stop model will set you back more than three times as much in Pennsylvania as in Belgium. Maintenance, repairs and inspections all cost more in America, too.

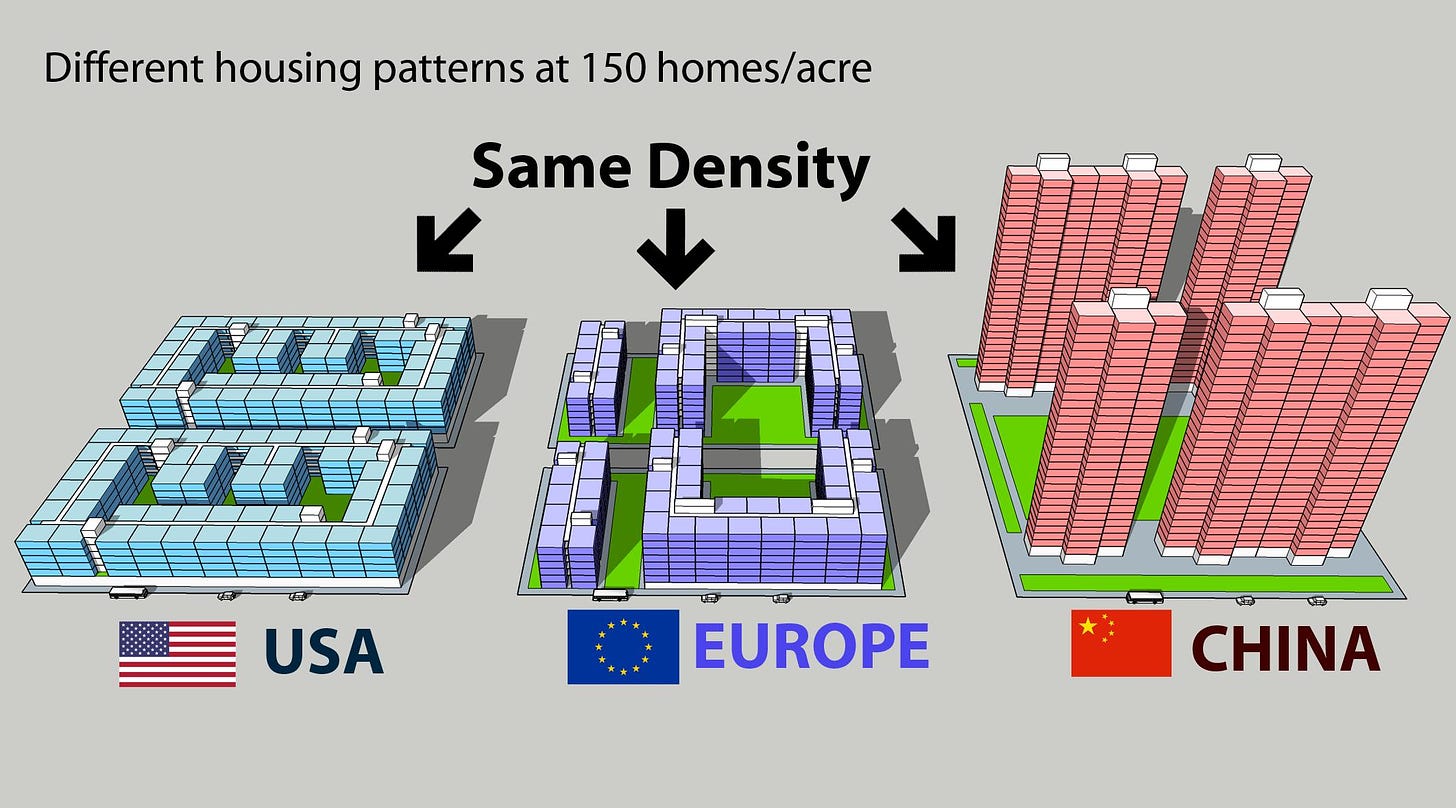

The Europeans have a standard building code for elevators, and they build lots of small ones, large enough for a wheelchair and one additional person. They do not let the perfect (and huge) be the enemy of the good. We instead impose tons of requirements, force everything to have its own uniquely American supply chains, and due to various requirements our labor costs are, like the most famous of elevators, through the roof.

This and other similar limiting factors hugely raise the cost of housing construction.

The solution to elevator regulations could not be simpler.

The European Union has a perfectly good set of rules. They work. Adapt those.

Similarly, we can copy their rules about what buildings require multiple staircases.

Or even better, let developers choose. You can either follow the local rules, or you can follow the EU rules. Easy. Simple. One page bill.

Yes, that means that various first responders might not be able to use some elevators to transports some types of equipment. But when Switzerland has twice the elevators per capita as New York City, the first responders cannot use the non-existent elevators at all.

The bigger apartment buildings, where the amount of passenger traffic and number of apartments served justifies a larger size, will still choose to build big. The market will demand it. And all those little buildings can get little elevators.

There is also the problem of the elevator unions, which it seems are of the pure rent extraction variety.

Architects have dreamed of modular construction for decades, in which entire rooms are built in factories and then shipped on flatbed trucks to sites, for lower costs and greater precision. But we can’t even put elevators together in factories in America, because the elevator union’s contract forbids even basic forms of preassembly and prefabrication that have become standard in elevators in the rest of the world. The union and manufacturers bicker over which holes can be drilled in a factory and which must be drilled (or redrilled) on site.

Manufacturers even let elevator and escalator mechanics take some components apart and put them back together on site to preserve work for union members, since it’s easier than making separate, less-assembled versions just for the United States.

Ryan Smyth: And if you’re in multifamily you know how unreliable most elevators are and the exorbitant ongoing maintenance costs involved. They usually take days to fix and the down time hammers resident satisfaction.

Bryan: When this sort of rent-seeking happens all of us pay for it. A lift should not cost five times less in *Switzerland*.

Noah Smith: The problem with American unions is not that they exist. It’s that too many of them look backward to the 1950s and want to RETVRN instead of embracing modern technology. Unions elsewhere are more forward-looking.

Noah is exactly on point.

If the union uses its position to get higher pay and better working conditions, up to a rather high point that seems fine and often actively good. Costs go up, but the workers benefit in line with costs.

If the union is as described here, and engaged in active sabotage and massive driving up of costs in order to create makework? That is an entirely different scenario. The union only captures a small fraction of the additional costs and everything becomes hostile and terrible.

We need to find a way to ensure that extraction is in the form of higher wages, not in the form of enforced inefficiencies to create work, and to draw a clear distinction between those two modes.

Of course, the Elevator Theory of Housing, saying it explains housing costs, is going too far. This is a surprisingly large form and cost factor, since it restricts entire classes of construction, but not the main event.

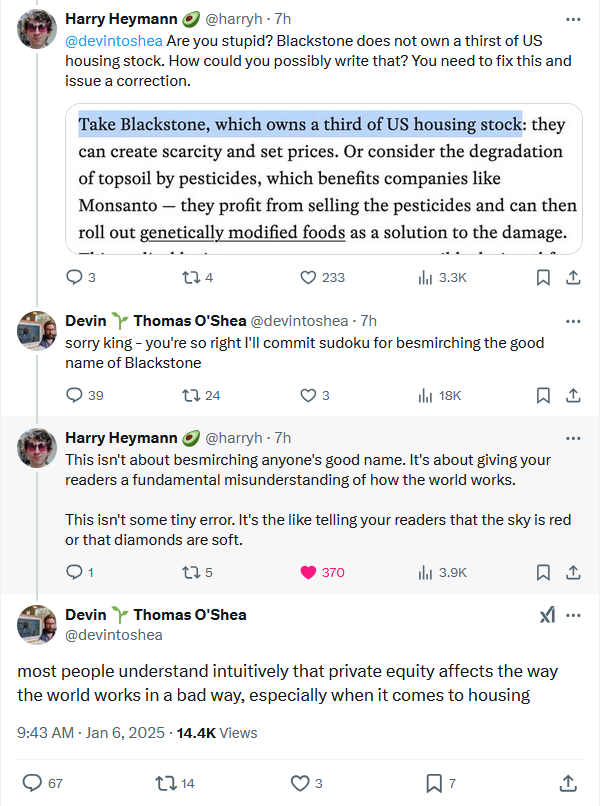

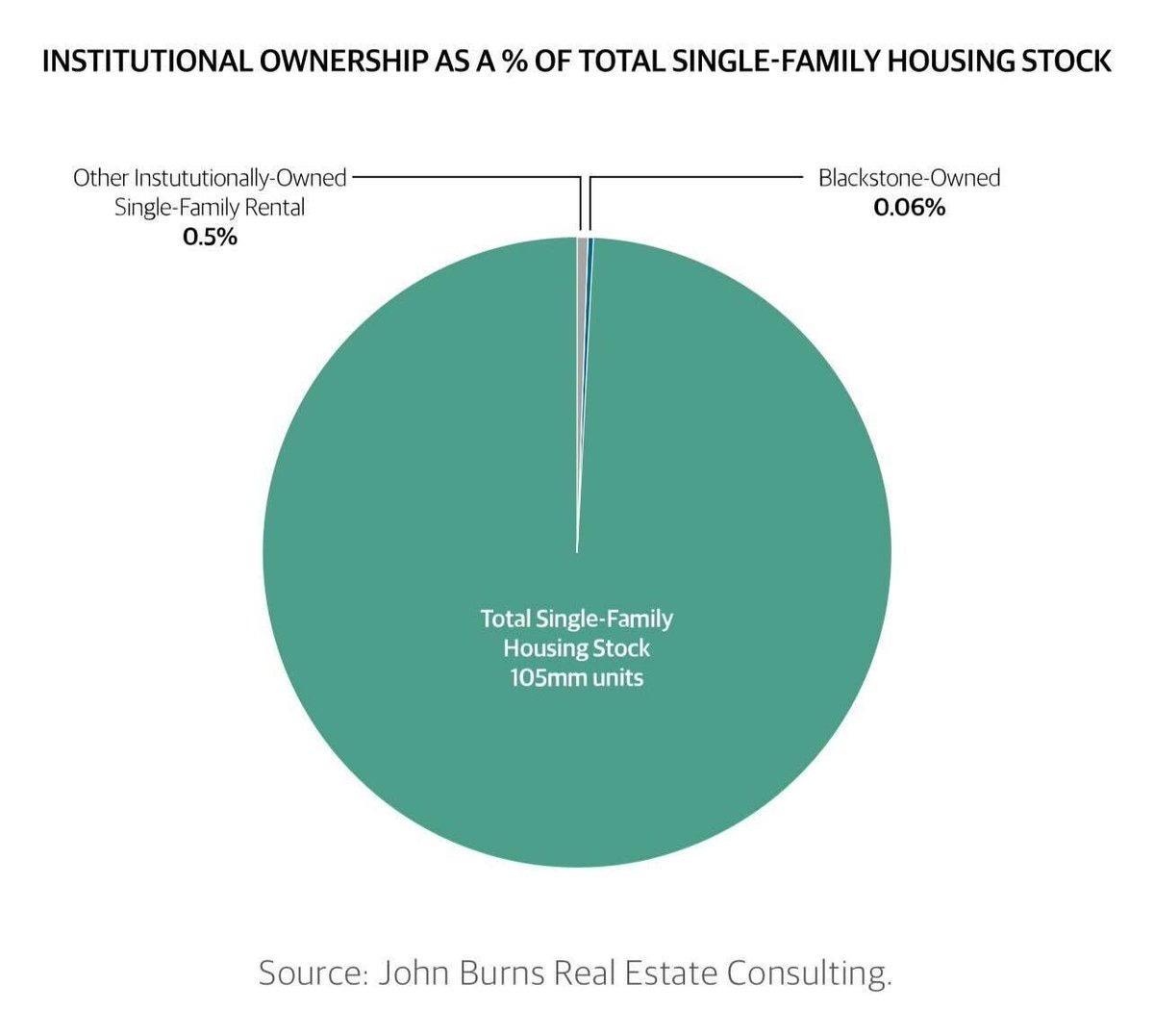

Hal Singer: Why have housing costs skyrocketed?

→ Progressives: Hedge fund/private equity have been buying up hundreds of thousands of homes. Pricing algorithms allow landlords to coordinate price hikes.

→ New York Times Op-Ed: No no. It’s the high cost of elevators and the elevator union!

Epilogue: The reason why elevator costs are so high is because of extreme concentration. It is not the fault of the elevator union or regulations, as Yglesias & YIMBYs would have you believe. His team could never blame companies (ie, prospective clients).

…

First, it’s a fixed cost, which shouldn’t enter the pricing calculus.

I love little windows like this into people’s thinking. Why would fixed costs matter?

More than that, he’s claiming that the reason costs are 5x higher in America is because of ‘extreme concentration’ without citing any evidence. Well, why exactly do we not see market entry? And what does this have to do with the central claims?

Matthew Yglesias: So many leftist professors are genuinely incapable of engaging with an argument on the merits and just resort to bullying.

The op-claims that US building codes make elevators more expensive than European or Asian elevators. Is there a rebuttal to that claim?

I know there is a lot of leftist fascination with private equity investments in housing but the explicit thesis of the investors is that regulatory barriers to supply will make these bets pay off.

Hal Singer: Who cares about elevator costs? Many buildings don’t have one, and for those that do, the elevator is a small % of total costs.

The whole reason most building do not have elevators is that we have made it prohibitively expensive in space and money to put in elevators to most buildings. Versus Europe, where a lot more buildings do indeed have elevators. And that difference also rules out a variety of housing construction and is hell on the disabled. That’s the whole thesis.

I do not know how much of the additional costs are due to unions as claimed, versus due to regulatory requirements, including labor shortages due to licensing requirements and immigration laws. All of that, of course, is constantly on my ‘fix it’ agenda all around.

This is not the biggest problem facing those who wish to build housing. Fixing it would still make a substantial difference, on the margin, to one of our biggest problems.

It remains mostly true, I think.

Tweets from Zack Weinberg: The reason everyone feels poor is because of housing prices and nothing else really matters is a view I hold stronger by the day.

Nabeel Qureshi: I genuinely think housing scarcity in/near cities explains 80%+ of the vibecession & the pessimism you encounter when you talk to practically anybody nowadays. It’s way worse than it used to be.

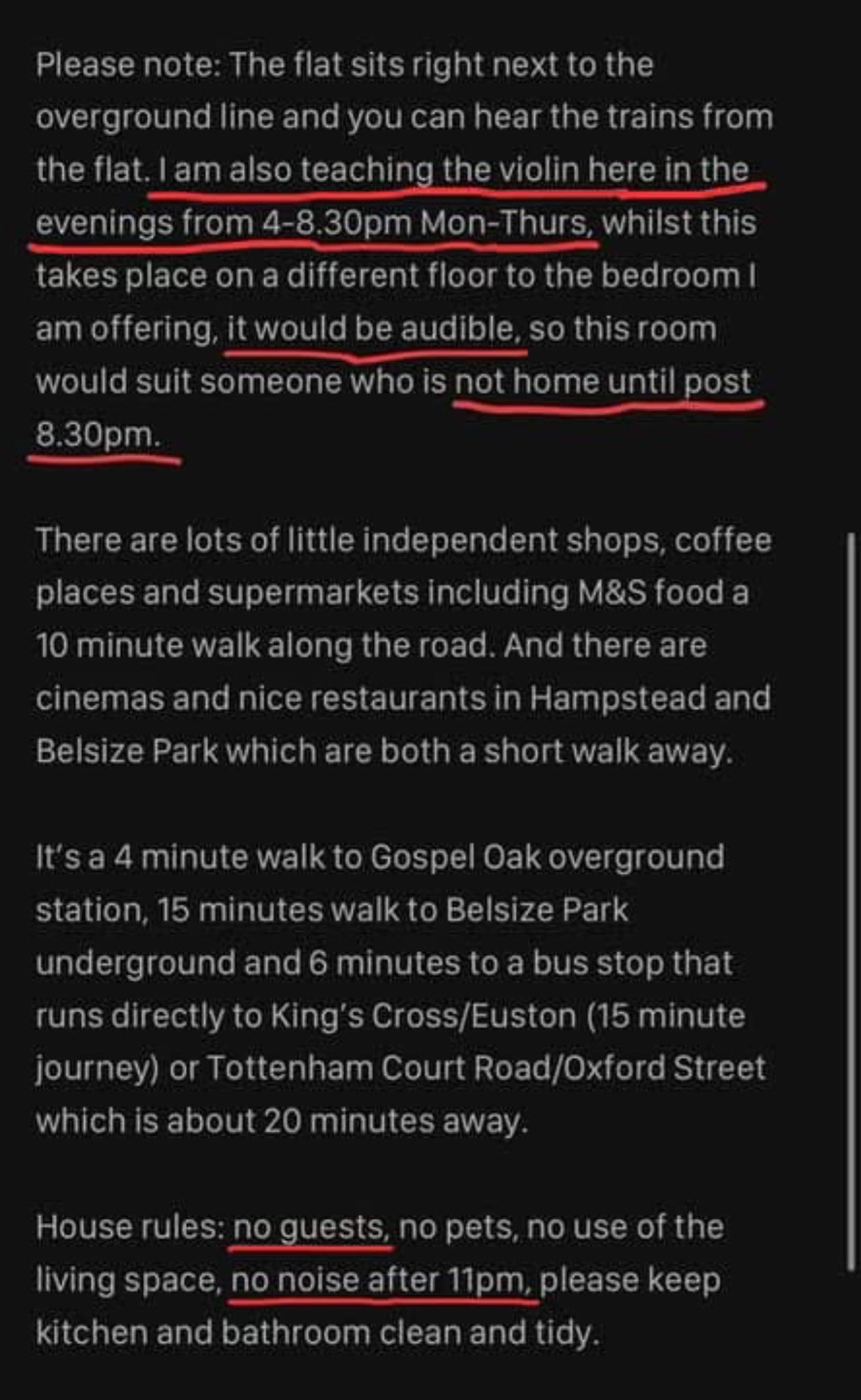

I’ve lived in both NYC and London and in both cities this has gotten significantly worse in my memory; you now often need to write personalized letters to landlords just to convince them to *rentyou their place, and 100+ applications for a single place is super common.

I sympathize with the “but the economy is so wonderful, look at the GDP number go up” people but sometimes I want to send them this quote & ask them to go talk to normal people once in awhile

I assume that the 100+ applications are because of rent control. Otherwise, you can respond by raising your price.

Tyler Cowen only attributes about 15% of the UK’s economic problems to NIMBY, or 25% if you count energy restrictions, disagreeing with well-informed British people he spoke to who said 50% or more.

I am in the 50% or more camp. Indeed I think this is more than 100%.

As in, if the UK was allowing and even encouraging energy including wind and nuclear, and allowed housing construction throughout the country, then the UK would be booming even with all its other problems.

Tyler’s main cause is that the UK is not making products people want to buy, that there was a specialization mismatch. There probably was a mismatch, but I think that dynamism would have allowed that to be solved without issue. I definitely would not blame 20% of the issue on Brexit.

Be careful what you wish for.

Pacific Legal Foundation: [In Sheetz v. El Dorado County] today the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that legislatures cannot use the permit process to coerce owners into paying exorbitant development fees. The ruling, a major victory for property rights, will remove costly barriers to development, thereby helping to combat the housing crisis.

The fee in question was $23,000, supposedly for traffic impact. It is obviously crazy to claim that a single family home will cause that much damage to traffic. I could see a case that it could lower property values by that much by increasing supply, by lowering each of 230 properties by $100 or something like that, although the owner intends to live on the property.

If this changes the rule from ‘you can build a house but you owe us $23k’ to ‘you can build a house and pay us $230’ then that is good on the margin.

I worry that is not the relevant margin. Instead, I worry that this payment, while outrageous, is also a mostly non-destructive and not so distortionary tax. If your new home is not generating $23k in surplus for you, then there is no great loss that you could not build it, and if you have an empty lot then the purchase price is now presumably $23k lower. So all you are doing it imposing a tax on the value of land, which is one of the best ways to tax. In exchange, the city feels good about letting you build, and is less inclined to impose other barriers.

If they tried to charge $230k instead, that seems a lot worse, but this seems fine?

Yes in God’s backyard? Six states propose bills allowing various charities to get around zoning laws or get tax advantages for building affordable housing. I do not see any reason to give preferential treatment to religious organizations, or to give to them a large share of the surplus available from building new housing. It is still miles better than not building the housing. Paris is worth a mass.

Ben Yelin: MD Senate currently debating one of Gov. Moore’s housing measures that you’ve written about! My own Republican State Senator is excoriating it.

Funny twist: After attacking the bill for 20 minutes about how this bill was unfair to landlords, he says he’s going to vote for it because he was able to secure amendments that made it better.

Matthew Yglesias: He’s complaining about legislation “battering the state’s landlord community” 😂😂😂

Alexander Turok: Many landlords own one or two properties. They’re not all millionaires.

Yes. One could argue that it would be better if identical housing was more expensive, rather than housing being cheaper, so that those who own the existing housing stock can profit off of those so unwise as to need to rent or buy. It is a preference one can have.

Or perhaps this is the true NIMBY?

It’s basically this, via Scott Lincicome.

Jeff Collins: A Los Angeles County judge found that charter cities aren’t subject to Senate Bill 9, the 2021 “duplex” law that allows up to four homes to be built on a lot in single-family neighborhoods.

The law fails to accomplish its stated purpose of creating more affordable housing, and therefore, doesn’t meet the high bar of overriding local control over zoning, Superior Court Judge Curtis Kin said in a ruling released Wednesday, April 24.

SB 9 “is neither reasonably related to its stated concern of ensuring access to affordable housing nor narrowly tailored to avoid interference with local government,” Kin wrote.

…

” ‘Affordable’ refers to below market-rate housing,” Kin wrote. The state gave “no evidence to support the assertion that the upzoning permitted by SB 9 would result in any increase in the supply of below market-rate housing.”

Yelling ‘the whole point of building more housing is to lower the market rate so all the housing is more affordable, you absolute dimwit fwads’ might feel good but the polite version does not seem to be working.

So, restate the stated purpose, then? Or require that one of the four homes be ‘affordable housing’ in the narrow sense?

Or perhaps something more drastic, like removing all zoning over residential and commercial buildings entirely from the bastards (they can keep the industrial restrictions), if that’s how they want to play it, provided you include at least some ‘affordable housing’?

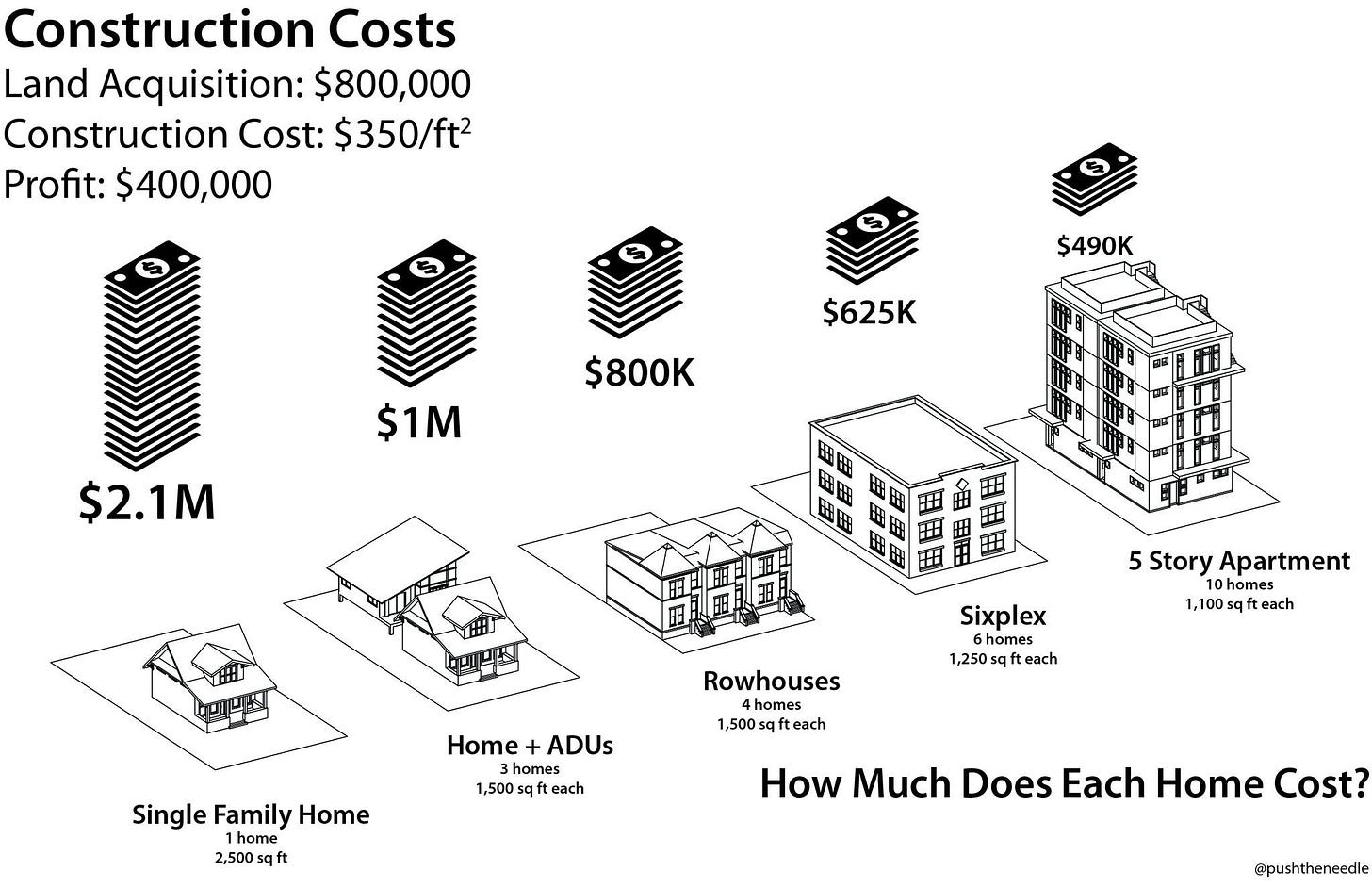

Emmett Shear explaining once again that if you stop restricting supply of housing, cost to buy will converge to cost of construction, which would drop prices in areas like Manhattan by more than half.

Crossover issue: Using federal subsidies for a housing project can trigger NEPA, at which point you might well be might better off without the subsidies. Even if we do not fix things in general we should absolutely change this rule, so that subsidies alone do not trigger NEPA.

Governor of Oregon uses legos to illustrate that when demand exceeds supply prices go up and poorer people can’t buy houses, whereas if you build more houses then prices go down and also everyone can have a house. Quite good.

Does this help?

Tesho Akindele: Density allows everyday people to outbid the rich for land.

This is not quite right, since cost per square foot goes up if you build higher, and also if you go bigger as a builder you will want bigger profits. It does seem mostly right, and it excludes the impact on overall supply and thus price level.

I doubt this line will work. It does have the benefit of being true:

Michael Cannon: Rent control does not make apts cheaper. It alters the price, not the underlying economic reality that gives rise to that price.

IOW, the apt is still expensive. RC just lets tenants consume surplus it steals from landlords/other renters—until quality falls to match the price.

Cannon’s fifth rule of economic literacy: The price is never the problem.

Or, on the flip side, wow.

Alec Stapp: This article from the London School of Economics is quite possibly the worst housing policy analysis I’ve ever seen. What’s their magic solution that gets around the law of supply and demand?

Headline: “Solving the Housing Crisis Without Building New Homes.”

Stephen Hoskins: I am begging the London School of Economics to understand that houses provide both shelter and location.

We’re inventing new forms of “there are more vacant homes than homeless people” every single day.

The thread has more details, but seriously, I can’t even. No, a bunch of price controls and redistribution is not magically going to fix having less supply than demand, and forcing the nominal official ‘price’ to be a non-economic number does not help.

And no, housing in places people do not want to live does not substitute for housing in other places where those people do want to live. Although I do think we can and should do some work to give people reason to want to move to the less desired places, especially if they are currently homeless. But the homeless mostly do not want that.

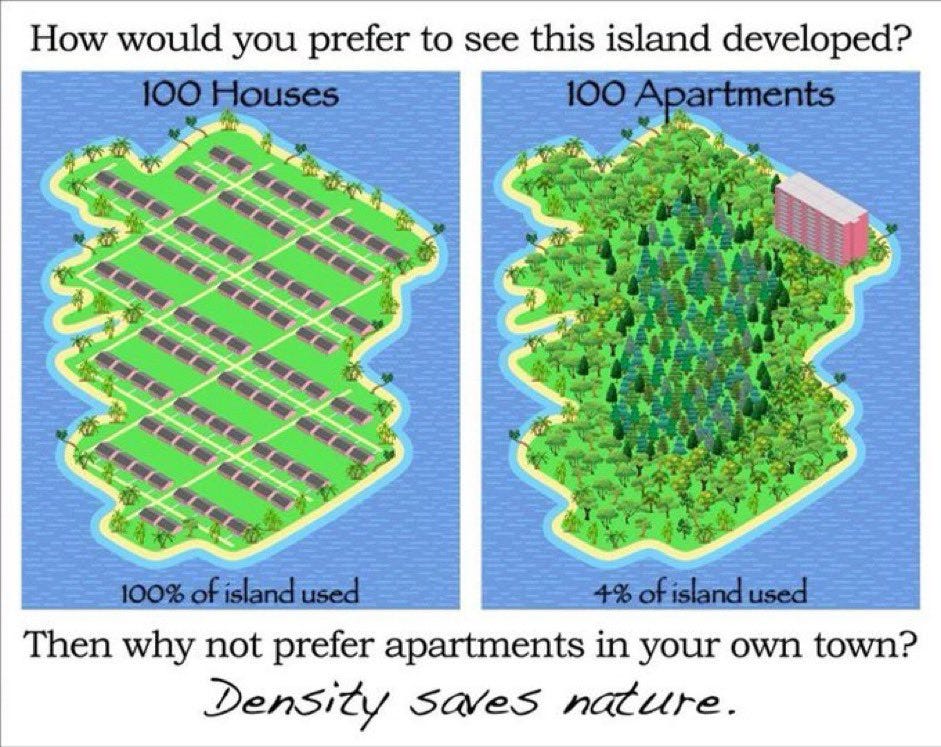

Three huge reasons.

-

People in denser areas consume vastly less carbon.

-

People in denser areas have lower fertility.

-

People in denser areas take up a lot less space.

Or you could look at it like this.

Sam: Urbanism protects rural and natural land whereas suburban sprawl frequently requires paving over natural landscapes and chopping down tons of trees.

Jason Cox: It really wrecks some people’s brains to learn I’m pro urbanism largely ~because~ I’m pro rural & agricultural areas remaining such.

They’re so excited to let me know I’m a clueless urbanite that doesn’t know where food comes from or what freedom looks like in my crime infested city abode without realizing I live much of the year on a working rural farm.

Both areas add value to society and the first shouldn’t be allowed to swallow the second unchecked because we lack the will to let cities be cities.

We all know the various definitions of democracy.

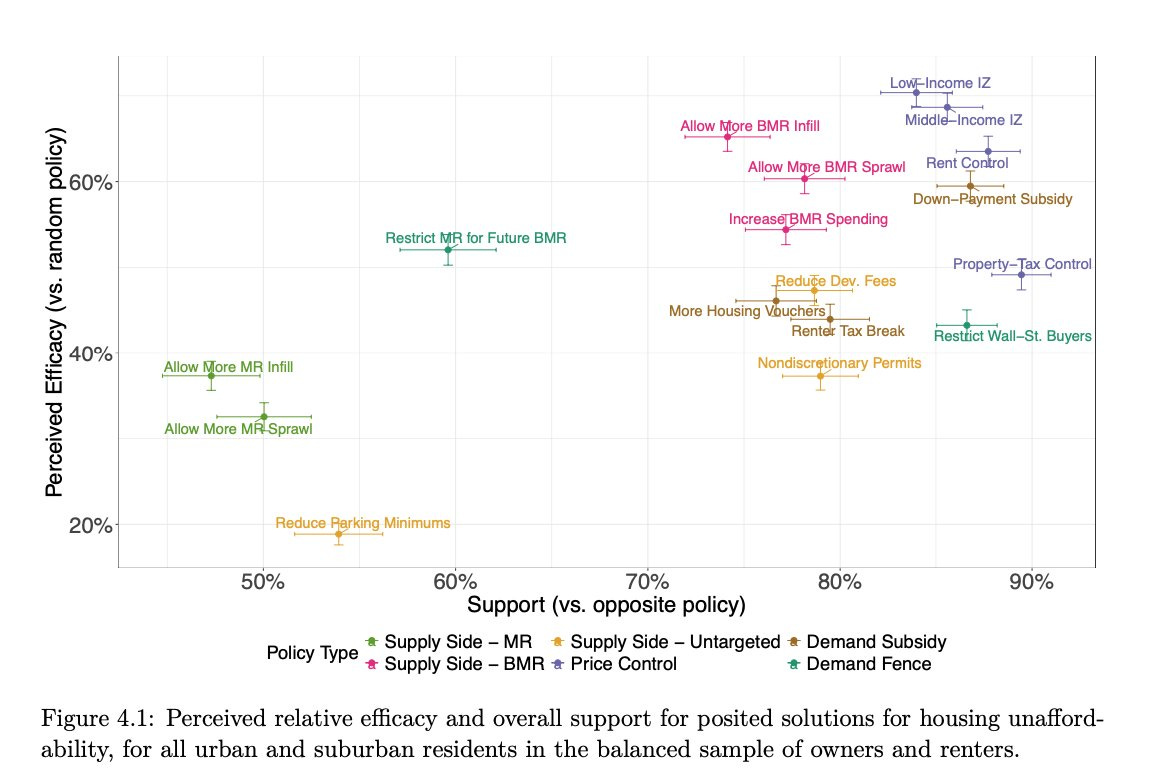

One major problem with democracy is people do not know economics. It shows.

Rent control polls around 87%. The only thing ahead of it is ‘property tax control’ meaning California’s Prop 13, a true nightmare of policy arguably worse than rent control.

The people want to not pay taxes, and to not pay market rent, and for existing residents to collect these economic rents forever, and to the extent they realize there is a price to pay for those things (beyond that no one can ever move) they want others to fit the bill.

They also want a ‘renter tax break’ and housing vouchers to go with the homeowner tax break. Why not give everyone a tax break and free money? Oh. Right.

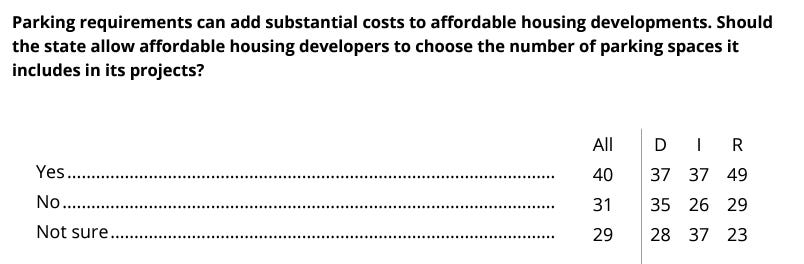

Meanwhile, the policies that are underwater are ‘allow people to build apartment buildings,’ and the close one is to reduce parking minimums.

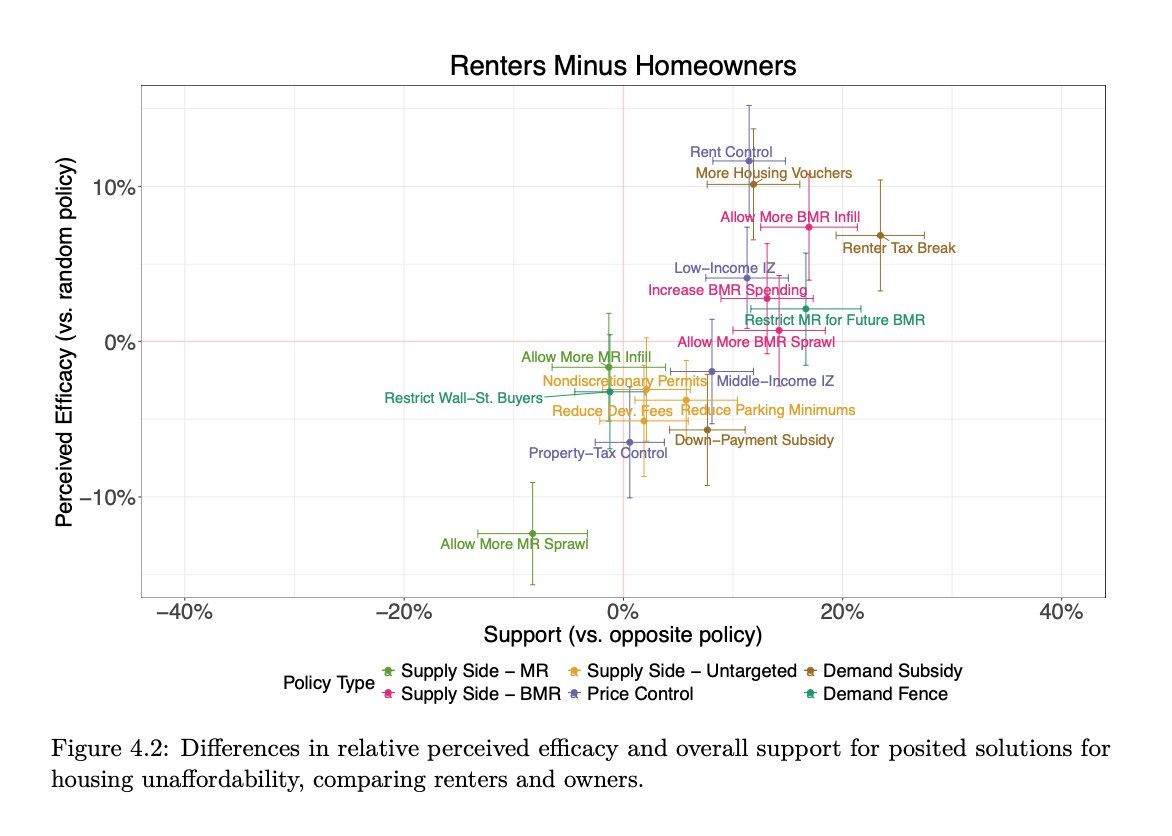

This is a chart of renter support for policies minus homeowner support:

So yes, their favorite policy in relative terms is ‘give us money,’ what a shock, but mostly there is not much voting one’s interest.

Chris Elmendorf: But do any of these policies matter when push comes to shove, and voters have to make tradeoffs with policies like abortion, health care, minimum wage, climate?

Yes. Rent control is near the top, w/ property-tax controls, IZ, and “Wall St” restrictions not far behind.

Also, people who want rent control and Wall. St. restrictions care a lot more about these policies than do their opponents, whereas opponents of market-rate infill development care somewhat more about it than do the proponents.

Joey Politano: Rent control, property tax control, down payment subsidies, and inclusionary zoning requirements all polling at like +80%.

I care quite a lot about opposing rent control. But I am the exception.

The whole thing is deeply sobering. People do not want the things that cause housing to exist.

Yet somehow, in many places, YIMBY policies are happening anyway. And in many other places, there is tons of popular NIMBY red meat available, and the politicians do not take it.

Something is working, and has been working for a while. One must ask, what allows our civilization to survive at all? Why do we get to tax things and pay some of the bills? Why is there some housing rather than none?

Missed the window for last time, but:

It’s happening?

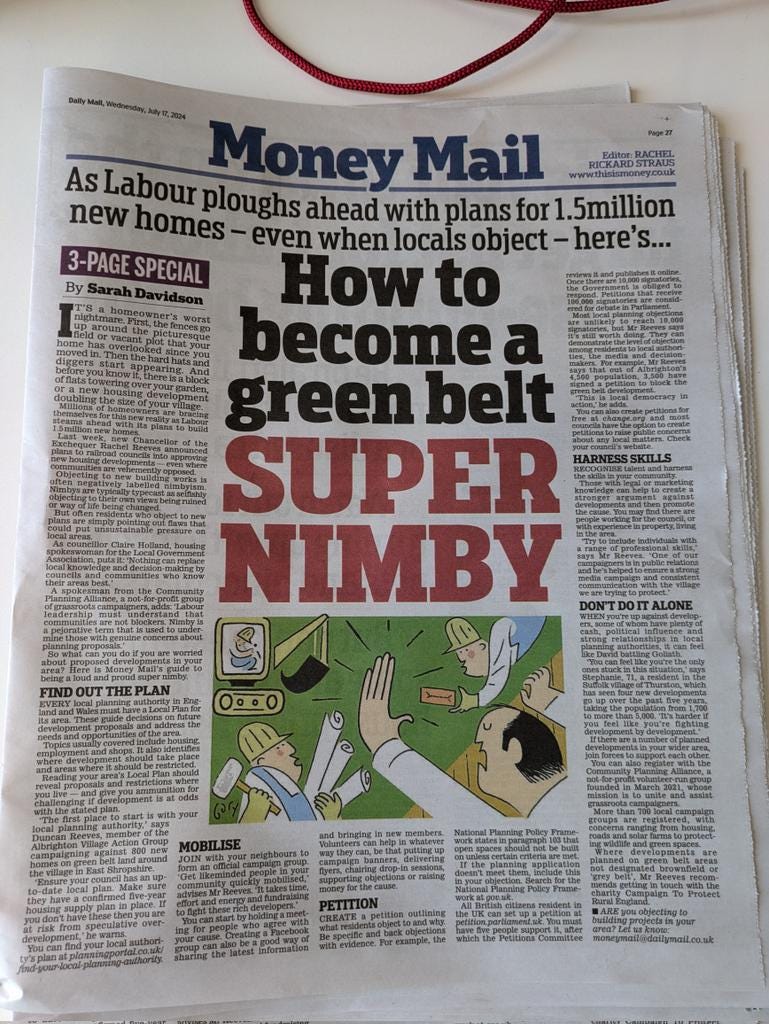

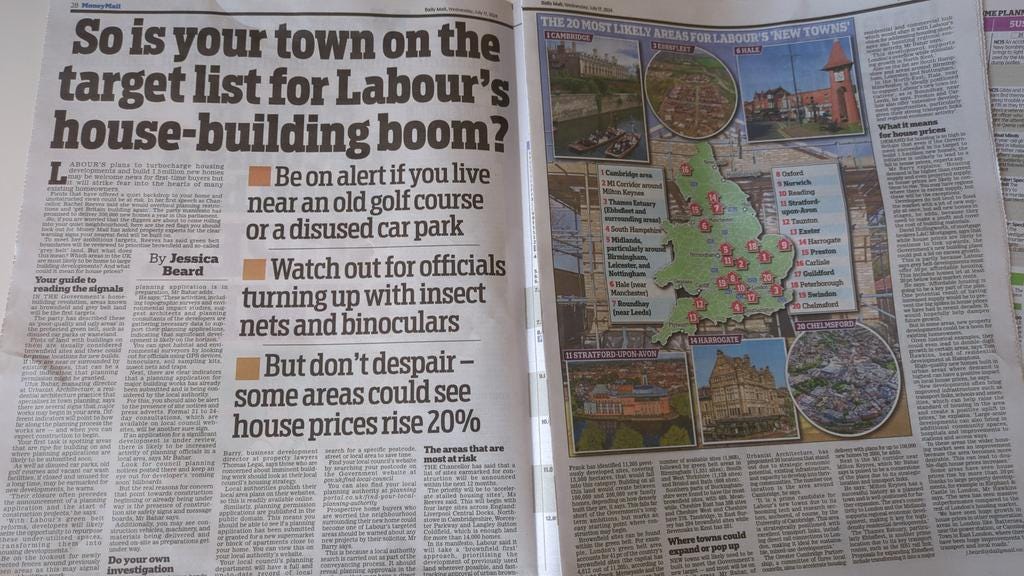

Rob Wiblin: Keir Starmer is the prince that was promised. 🔥🔥🔥

YIMBY Alliance: NEW: Local residents will lose the right to block housebuilding, Keir Starmer will announce today.

NEW: Keir Starmer ‘will unveil plans to build 1.5 million houses over five years by forcing councils to approve new homes, including on the green belt, warning that those who refuse will have development imposed upon them as part of a “zero tolerance” approach to nimbyism.’

I especially love this being called explicitly a “zero tolerance” approach to nimbyism.

The Times: The Labour leader will unveil plans to build 1.5 million houses over five years by forcing councils to approve new homes, including on the green belt, warning that those who refuse will have development imposed upon them as part of a “zero tolerance” approach to nimbyism.

If you give indigenous people the right to do what they want with their land, and it would be highly profitable to build housing on it, guess what?

Jason Crawford (quoting): “Because the project is on First Nations land, not city land, it’s under Squamish authority, free of Vancouver’s zoning rules. And the Nation has chosen to build bigger, denser and taller than any development on city property would be allowed.”

Warren Wells: As a non-indigenous person, I would simply avoid telling indigenous people what “the indigenous way” is.

Kane: The best parts of left nimbys losing their minds about indigenous people building new homes is the leftists telling the indigenous people they’re being indigenous wrong.

Scott Sumner points out this is very much the pro-wilderness solution, as those people have to live somewhere.

I have no idea if this is a complaint that is all that common. As usual with such matters, the people who are very loud mostly represent a highly unpopular viewpoint.

Stanford hates fun, but if you really hated or truly loved fun, perhaps you would get the law to do something about the fact that 94% of elevators on campus have expired permits? The author of the article is sufficiently onboard with hating fun that this is framed as an actual safety issue.

Sheel Mohnot: Caltrain deputy director built himself an apartment (with kitchen & shower) inside the Burlingame train station with $42k of public funds (each invoice <$3k), and it took 3 years for it to be discovered.

I demand a short documentary about this! I haven’t seen footage anywhere.

Jerusalem: knowing literally nothing else about this… go off king.

Jail?? you should hire him to figure out how to build housing this cheaply in California.

Jason Crawford: My main takeaway here is that you can build a home in CA for $42k as long as no one is watching.

Land trusts are super weird. Shouldn’t we either make who owns what properties public, and something you can take in a legal judgment, or not? Instead you can pay a small fee to get around those issues.