What we can learn from scientific analysis of Renaissance recipes

“a key change in how people constructed knowledge”

Multispectral imaging, proteomics, historical texts yield new insights into 16th-century medical manuals.

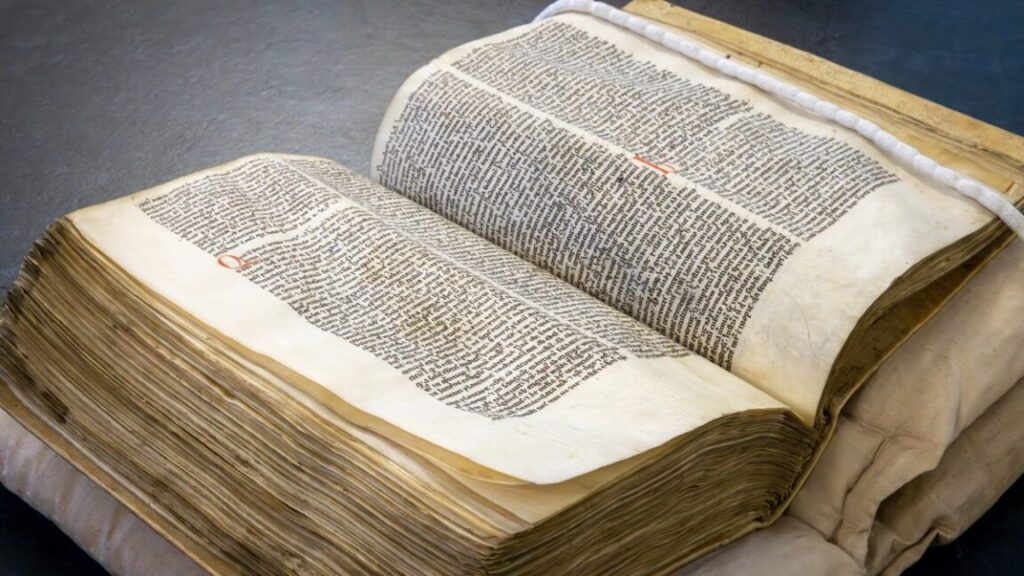

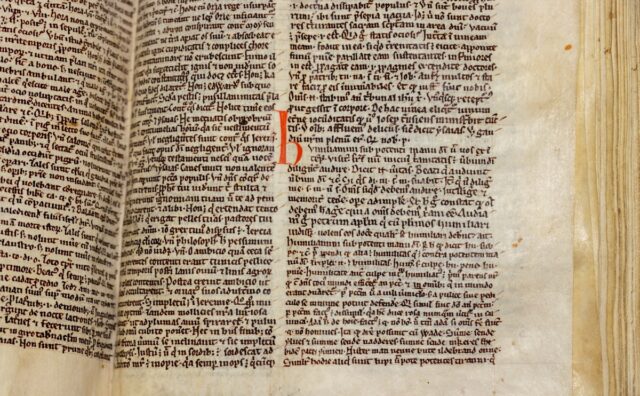

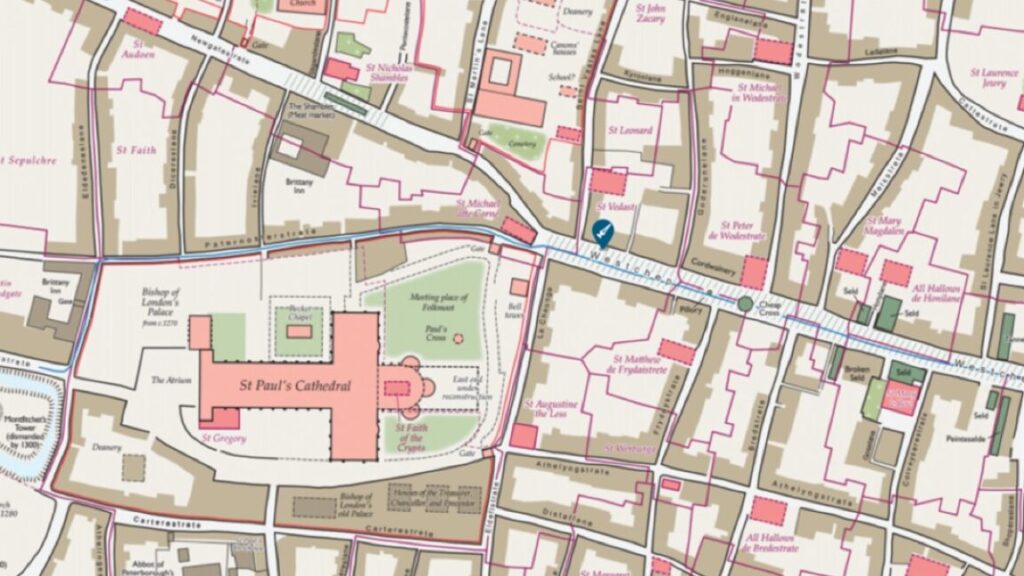

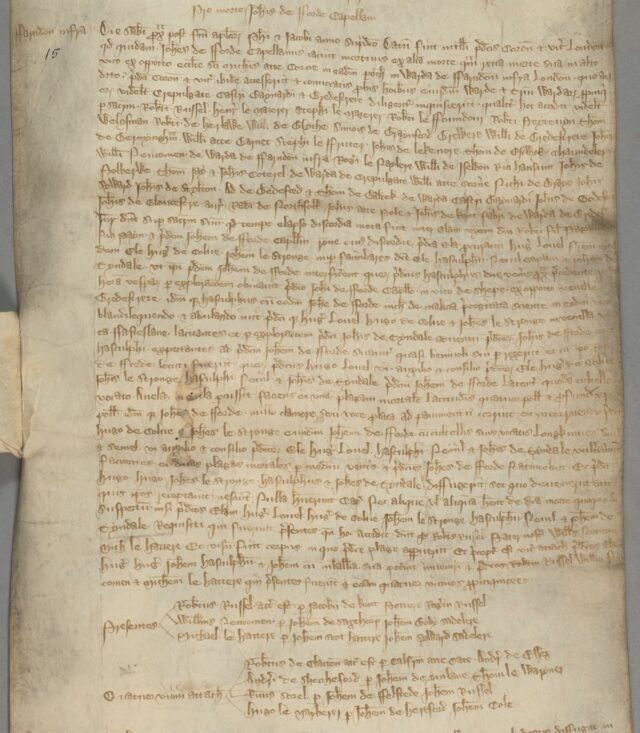

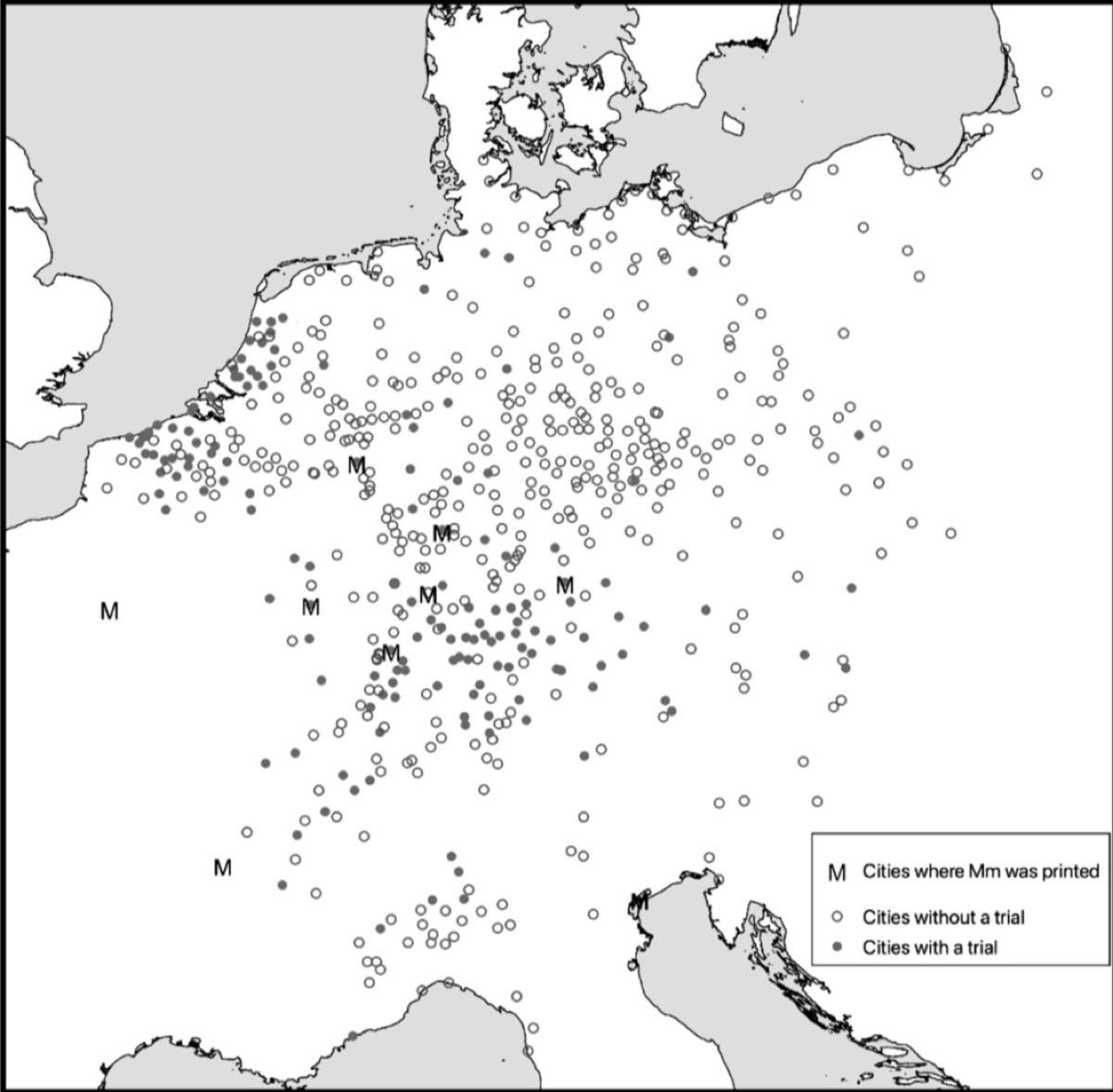

Credit: The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester

Forget “eye of newt and toe of frog/wool of bat and tongue of dog.” People in the 16th century were more akin to DIY scientists than Macbeth’s three witches when it came to concocting home remedies for everything from hair loss and toothache, to kidney stones and fungal infections. Medical manuals targeted to the layperson were hugely popular at the time, according to Stefan Hanss, an early modern historian at the University of Manchester in the UK. “Reader-practitioners” would tinker with the various recipes, tweaking them as needed and making personalized notes in the margins. And they left telltale protein traces behind as they did so.

Hanss is part of an interdisciplinary team of archaeologists, chemists, historians, conservators, and materials scientists who have analyzed trace proteins from the fingerprints of Renaissance people rifling through the pages of medical manuals. The team reported their findings in a paper published in The American Historical Review. It’s the first time researchers have used proteomics to analyze Renaissance recipes, enhanced further by in-depth archival research to place the scientific results in the proper historical context.

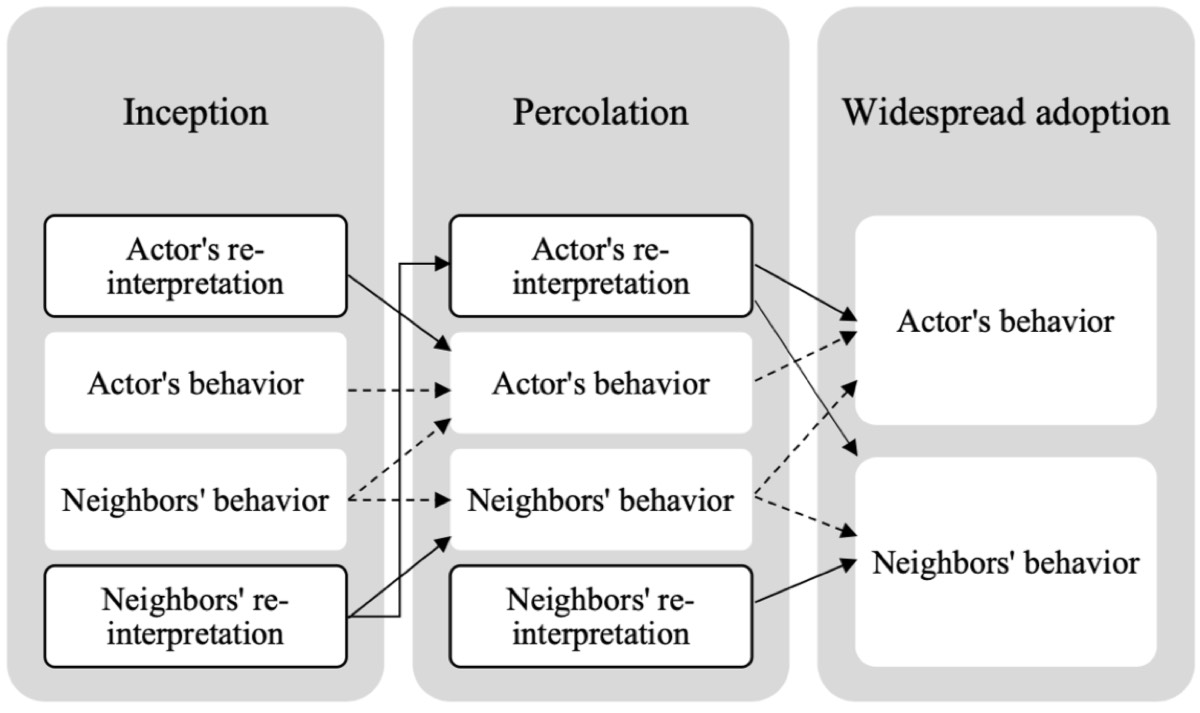

“We have so many recipes of that time, [including] cosmetic, medical, and culinary recipes, as well as handwritten recipes passed down for generations,” Hanss told Ars. “It’s really a key element of Renaissance culture, and [the manuscripts] are all covered with scribbled marginalia of [past] users. Experimentation was everywhere. It’s not only about book-learned knowledge but hands-on practical knowledge. It’s a key change in the way people constructed knowledge at that time.”

As previously reported, a number of analytical techniques have emerged over the last few decades to create historical molecular records of the culture in which various artworks were created. For instance, studying the microbial species that congregate on works of art may lead to new ways to slow down the deterioration of priceless aging art. Case in point: Scientists analyzed the microbes found on seven of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings in 2020 using a third-generation sequencing method known as Nanopore, which uses protein nanopores embedded in a polymer membrane for sequencing. They combined the Nanopore sequencing with a whole-genome-amplification protocol and found that each drawing had its own unique microbiome.

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics is a relative newcomer to the field and is capable of providing a thorough and very detailed characterization of any protein residues present in a given sample, as well as any accumulated damage. The technique is so sensitive that less sample material is needed compared to other methods. And unlike, say, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, it’s also capable of characterizing all proteins present in a sample (regardless of the complexity of the mixture), rather than being narrowly targeted to predefined proteins. In 2023, scientists used this approach to discover that beer byproducts were popular canvas primers for artists of the Danish Golden Age. Hanss et al. are extending this methodology to Renaissance medical manuals.

A thriving DIY medical marketplace

This latest study has its roots in an event Hanss organized a few years ago called “Microscopic Records,” which brought together experts in various scientific fields and early modern historians. One of the master classes on offer focused on proteomics. Hanss was intrigued when he learned that researchers had extracted proteins from the lower-right and left corners (i.e., where contact occurs when one turns a page) of archived manuscripts in Milan. “I thought, we must have a conversation about doing this for Renaissance recipes,” said Hanss. “We know there was experimentation, but we couldn’t really trace it. This is really the first time that we’ve sampled and identified and contextualized biochemical traces of materials.”

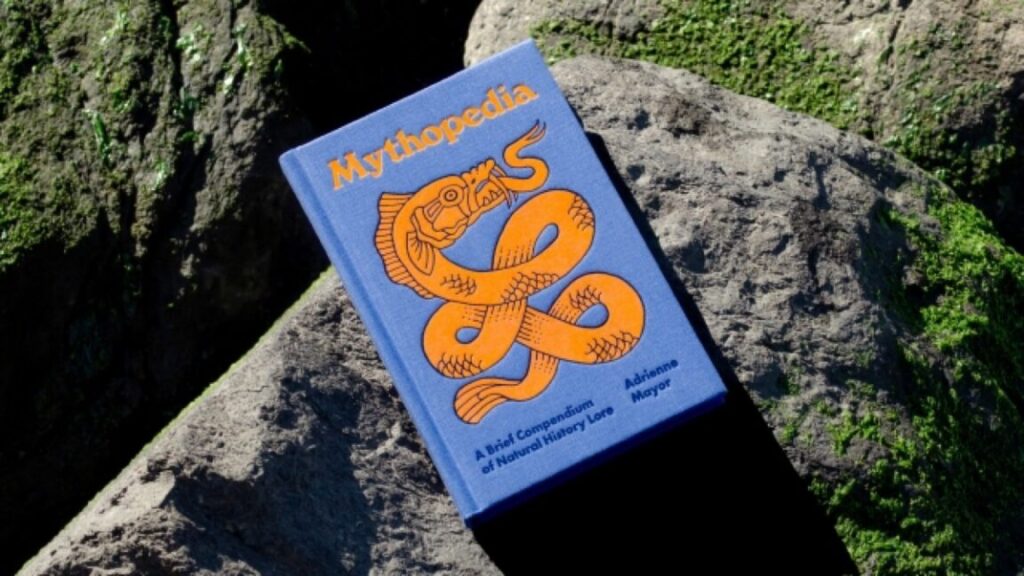

Hanss et al. focused on two 1531 German medical manuals published by 16th-century physician Bartholomäus Vogtherr: How to Cure and Expel All Afflictions and Illnesses of the Human Body and A Useful and Essential Little Book of Medicine for the Common Man. The two tomes are bound together into a single volume and are part of the collection of the John Rylands Research Institute and Library at Manchester. The recipes included domestic remedies for brain disease, infertility, skin disorders, hair loss, wounds, and various other severe illnesses, written in the vernacular and targeted at the common populace.

It was a relatively new genre at the time, per the authors, a kind of everyday DIY science, since the manuals encouraged at-home hands-on experimentation. In 16th-century Augsburg (a printing hub), “experimentation was everywhere,” and the city boasted a thriving medical marketplace. It’s clear that people used the Rylands copies of Vogtherr’s manuals for their own experiments because the margins are filled with scribbled notes and comments dating back to that period.

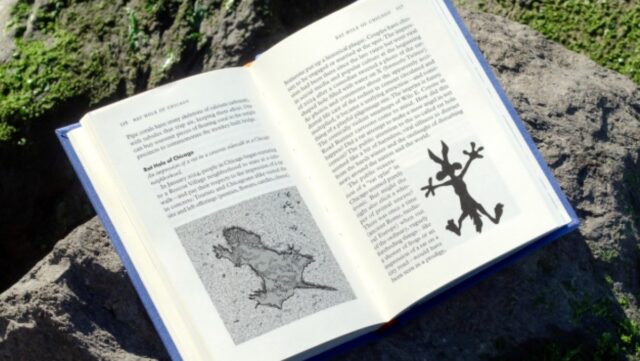

The first step was to take high-resolution photographs and then run the pages through multispectral imaging (including infrared and UV wavelengths), which helped them recover the most faded, previously illegible handwriting, such as on the inside cover. One scribbled note turned out to be instructions to use a mixture of viola and scorpion oil as a treatment for ulcers. Then they sampled various pages from the manuals for the proteomics analysis, focusing on areas where Renaissance users would be most likely to rest their writing hand or leave fingerprints. That’s also why they avoided the bindings, which are far more likely to be handled by modern-day conservators.

While proteomics cannot establish the dates of specific samples, the team was able to distinguish between contemporary and old peptides based on degree of degradation (such as oxidation). The quantity of peptides detected was also a clue. In fact, the team ended up excluding one of the samples from the final paper because there was such a significantly higher number of peptide results (2,258) than expected, compared to all the other samples (which ranged from 40 to 210 peptides). And for these two particular manuals, “They were in use for more than a hundred years and we know the [users’] names,” said Hanss. “We could make an informed interpretation based on other recipes at the time, and letters exchanged between [Renaissance] medical practitioners.”

The handwritten marginalia are a fascinating window into how people experimented with and tweaked various Renaissance domestic remedies. For those suffering from urinary stones, for instance, a “reader-practitioner” commented that during painful flare-ups, “parsley powdered or soaked in wine” could be effective. There are references to the benefits of broadleaf plantain juice (administered anally), and eating scarlet hawthorn leaves.

The proteomics results confirmed, among other things, the presence of many popular ingredients used in the recipes, such as beech, watercress, and rosemary traces found next to hair loss remedies—commonly attributed to an “overheated brain—along with cabbage and radish oil, chicory, lizards, and, um, human feces. (Just how badly do you want to grow back that thinning hair?) The manuscripts also include recipes for blonde hair dyes. The analysis revealed traces of plants with particularly striking yellow flowers on those pages. “That is a common theme in cosmetic and medical discourse at the time,” said Hanss. “The idea was to look for resemblances between the remedies and what you wish to achieve in terms of the treatment.”

One of the most remarkable results, per Hanss et al., was the recovery of collagen peptides from hippopotamus teeth or bone, pointing to the global circulation of more exotic ingredients in the 16th century. Hippo teeth were said to cure kidney stones and “take away toothache,” and were even used to make dentures.

Hanss et al. also found that several of the proteins they found had antimicrobial functions, such as dermcidin (derived from human sweat glands), which kills E. coli and yeast infections like thrush. The samples also yielded insight into how Renaissance people’s bodies responded to the remedies. Traces of immunoglobulin, lipocalin, and lysozyme are indicators of an active immune response, for instance.

Hanss is so pleased with these initial results that he hopes to launch a large-scale project to extend this interdisciplinary approach to other collections of medical manuals. He also hopes to further improve the dating methodology. “The ingredients for success are there,” said Hanss. “It’s not only that we found new answers to old questions, but we are now in a position to ask completely new questions.”

The American Historical Review, 2025. DOI: 10.1093/ahr/rhaf405 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

What we can learn from scientific analysis of Renaissance recipes Read More »