WB axes Shadow of Mordor maker in setback for clever, sadly patented game system

Game studio Monolith, part of Warner Bros. Games until yesterday’s multi-studio shutdown, had a notable track record across more than 30 years, having made Blood, No One Lives Forever, Shogo: Mobile Armor Division, F.E.A.R., and, most recently, the Lord of the Rings series, Shadow of Mordor and Shadow of War.

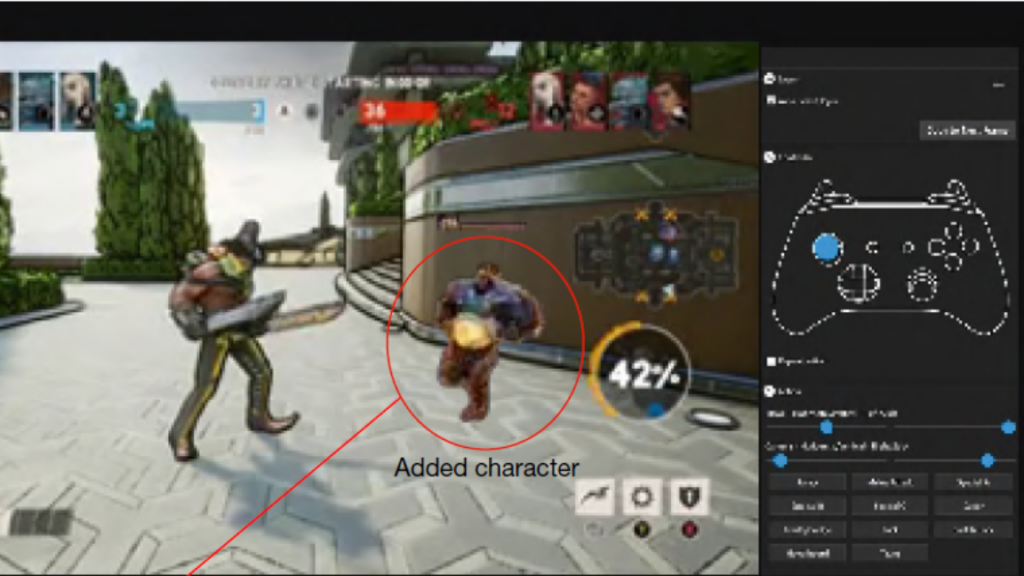

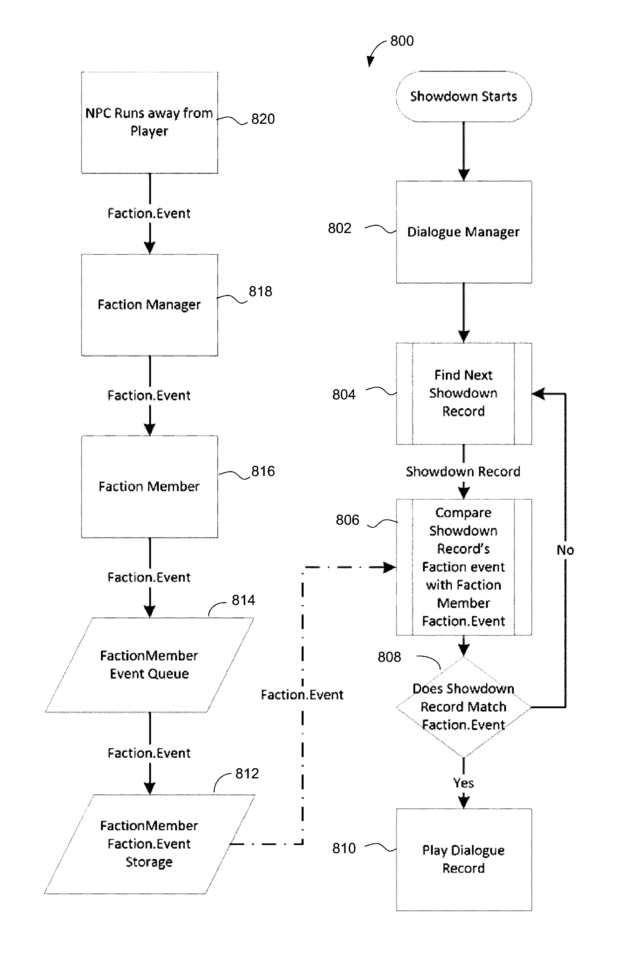

Those games, derived from J.R.R. Tolkien’s fiction, had a “Nemesis System,” in which the enemies that beat the player or survive a battle with them can advance in level, develop distinct strengths and weaknesses, and become an interesting subplot and motivation in the game. Monolith’s next game, the now-canceled Wonder Woman, was teased more than three years ago, and said to be “powered by the Nemesis System.”

Not only will Wonder Woman not be powered by the Nemesis System, but likely no other games will be, either, at least until August 2036. That’s when “Nemesis characters, nemesis forts, social vendettas and followers in computer games,” patent US2016279522A1, is due to expire. Until then, any game that wants to implement gameplay involving showdowns, factions, and bitter NPC feelings toward a player must either differentiate it enough to avoid infringement, license it from Warner Brothers, or gamble on WB Games’ legal attention.

It’s bad enough that talented developers were let go. That one of their most notable innovations ends up locked up in a corporate vault, for more than a decade after they ceased to exist, is quite the sad footnote.

Nobody wants to end up Crazy Taxi‘d

Credit: Warner Bros./USPTO

That WB Games was granted this patent is eye-opening, but not necessarily shocking. For 20 years, Namco held a patent on loading screen mini-games. That patent was issued despite plenty of “loading screen games” existing before 1995, including Invade-a-load. Similar patents have been issued for the Mass Effect dialogue wheel, a “sanity meter” in Eternal Darkness, and basically the entire concept of Crazy Taxi, such that Sega tried to eliminate The Simpsons: Road Rage entirely and recoup all its revenue. That case was settled out of court, and you haven’t seen Crazy Taxi-like arrows above game vehicles to this day. Ars’ Kyle Orland wrote in 2007 about how a 1989 patent for racing against your best time, or a “ghost racer,” led to license payments from games made in the mid-2000s.

WB axes Shadow of Mordor maker in setback for clever, sadly patented game system Read More »