2026 Australian Grand Prix: Formula 1 debuts a new style of racing

Just like the Apple movie?

The key is understanding how to conserve energy across a lap. Oh, and be reliable.

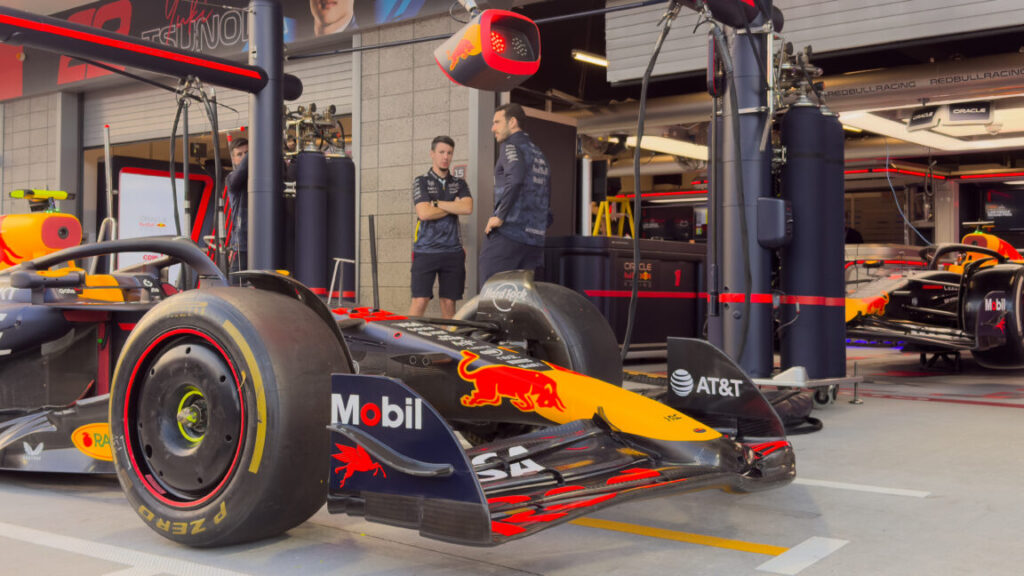

Formula 1’s 2026 season got started in Australia this weekend. Credit: Alessio Morgese/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Formula 1’s 2026 season got underway this past weekend in Melbourne, Australia. Formula 1 has undergone a radical transformation during the short offseason, with new technical rules that have created cars that are smaller and lighter than before, with new hybrid systems that are more powerful than anything since the turbo era of the 1980s—but only if the battery is fully charged.

The changes promised to upend the established pecking order of teams, with the introduction of several new engine manufacturers and a move away from the ground-effect method of generating downforce, which was in use from 2022. For at least a year, paddock rumors have suggested that Mercedes might pull off a repeat of 2014, when it started the first hybrid era with a power unit far ahead of anyone else.

That wasn’t entirely clear after six days of preseason testing in Bahrain, nor really after Friday’s two practice sessions in Melbourne, topped by Charles Leclerc’s Ferrari and Oscar Piastri’s McLaren, respectively. The Mercedes team didn’t look particularly worried, and on Saturday, we found out why when George Russell finally left off the sandbags and showed some true pace, lapping more than six-tenths faster by the end of free practice than the next-quickest car, the Ferrari of Lewis Hamilton.

It’s never done that before

It wasn’t all smooth running for Antonelli, who tore three corners off his car during the same practice session, giving his mechanics a monstrous job to rebuild it all in a few short hours for qualifying. That almost didn’t happen, until qualifying was interrupted with a red flag caused by an uncharacteristic crash for four-time world champion Max Verstappen, who ended up in a crash barrier right at the start of his first flying lap.

A rear lockup sent Max Verstappen into the barrier during qualifying. Paul Crock / AFP via Getty Images

“I’ve never experienced something like that before in my career. The rear axle just completely locked on, then of course you can’t save that anymore at that speed,” Verstappen told the media. Red Bull hasn’t yet revealed the precise cause of Verstappen’s crash, which forced him to start Sunday’s race from the back of the grid, but it’s likely related to the way the car’s electric motor can harvest more than half of the power output from the V6 engine.

Verstappen wasn’t the only driver caught out by unfamiliar hybrid behavior. Last year’s title hopeful and hometown hero Oscar Piastri looked to have the measure of his teammate (and reigning world champion) Lando Norris, but never even took the start of the race. On the way to the grid, Piastri took a little too much curb at turn 4, at which point his car delivered 100 kW more power than he was expecting; on cold tires, this spun the wheels, and before he could catch it, the car was in pieces and his weekend was over.

Ctrl-Alt-Del

If you are a relatively recent F1 fan, you may have only watched the sport during a period of extreme reliability. It was very much not always this way, and even when budgets for the top teams were two or three times what they’re allowed to spend now, cars broke down a lot.

Completely disassembling them and putting them back together overnight didn’t help, a practice that ended some years ago, but mostly it was technical rules that required teams to use the same engines for multiple races. Until 2004, you could use multiple engines in a single race weekend; by 2009, each driver was only allowed to use eight engines during a single season. Now, the limit is just three engines, and the same for the components of the hybrid systems, with grid penalties for drivers who exceed these limits.

Aston Martin got enough running this weekend to shave two seconds off its lap time deficit to the front-runners. Credit: Martin KEEP / AFP via Getty Images

That has been a rare occurrence of late, since the previous power units had been relatively stable since 2014 and were thus well-understood. But multiple drivers had issues this weekend in Oz. On Friday, we already discussed the vibration problem that limited Aston Martin’s running in preseason testing and during the first day of practice. That didn’t get much better for the team in green, which used Sunday’s race as a test session: Fernando Alonso completed 21 laps in total; Lance Stroll did 43 and actually took the finish—although it wasn’t classified, as the race distance was 58 laps.

But Aston Martin wasn’t alone in having problems. Williams has had its own trouble this year with a car that is uncompetitive and overweight, and Carlos Sainz missed the entire qualifying session after having a breakdown on his way back into the pit lane. On Sunday, Audi’s Nico Hülkenberg had to be pushed into the garage just before the start of the race with a power unit failure, marring what has otherwise been an excellent debut for the new power unit constructor, which took over the Sauber team.

Verstappen’s teammate, Isack Hadjar, had done the seemingly impossible for a Red Bull second driver and stepped up after Verstappen’s qualifying crash to claim third on the grid, behind the two extremely fast Mercedes drivers. But he only got as far as lap 10 before his power unit, the product of Red Bull’s in-house program with help from Ford, failed somewhat spectacularly, parking him by the side of the road. Five laps later, the (Ferrari-powered) Cadillac of Valteri Bottas broke down, too. Not quite the failure rate that some predicted, but six cars out of 22 still failed to make it to the checkered flag.

But it wasn’t all bad

That said, the other 16 cars did finish, including the Cadillac of Sergio Perez. Cadillac has managed to stand up a team from scratch and, since then, meet every deadline it needed to. Now, it has the rest of the season to show us it can make its car fast, something that equally applies to Williams and Aston Martin.

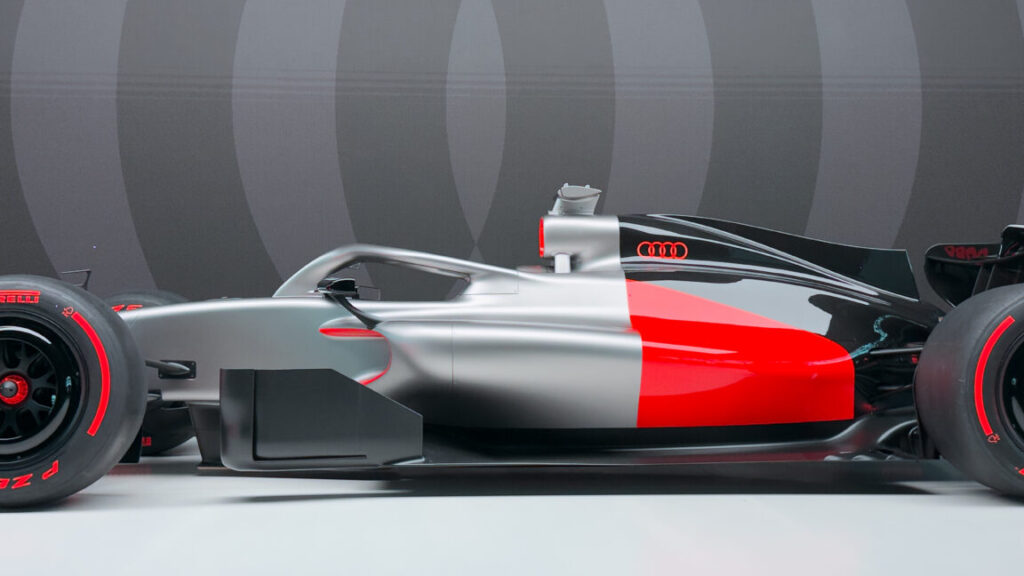

Audi looks to have landed in the midfield at the start of its F1 adventure. Credit: Joe Portlock/Getty Images

Audi had an almost as monumental task as Cadillac, designing and building a new power unit to install in what was the Sauber team before the German OEM took control. Aside from Hulkenberg’s problem, it had a pretty good debut. The cars lined up 10th and 11th for the race, and Gabriel Bortoleto showed off the talent that won him an F2 championship in his first year by finishing in 9th place, scoring the outfit points on its debut. Audi looks like a solid midfield contender, alongside Haas and Racing Bulls.

Alpine’s Pierre Gasly scored the final point, but that team, like Williams, looks a long way from making best use of its Mercedes power units and right now needs to combat a problem with understeer that affects its car in high-speed corners.

Russell initially battled Leclerc for the lead, passing and repassing each other several times over several laps, allowing a rejuvenated Hamilton to catch up with them. Russell was the meat in a sandwich between the two Ferraris until Hadjar’s crash called out the first virtual safety car. The two Mercedes took the opportunity to pit for new tires, undercutting their rivals in red.

The Ferraris of Leclerc and Hamilton probably weren’t fast enough to have won even if they’d pitted at the same time. They didn’t and finished in third and fourth, behind the victorious Russell with Antonelli in second place. In clean air, the Mercedes looked unstoppable in Melbourne, and the team clearly understands how to get the most out of these new power units compared to its customer teams.

A new style of racing

The peculiarity of these new hybrid power units has demanded a new way to be fast, particularly at the temporary circuit formed around the roads of Melbourne’s Albert Park, which lacks the heavy braking zones of most F1 tracks. This was evident with the cars decelerating well before the turn 9-10 complex as the engines diverted so much of their power away from the rear wheels and through the electric motor into the battery to use later in the lap. While not quite coasting, the drivers were clearly trying to maintain as much momentum as possible with little power actually going to the tires.

Twenty-two drivers, 22 opinions. Credit: Jayce Illman/Getty Images

Whether they approved of this or not seems to rest on whether they have a fast car.

“I thought the race was really fun to drive. I thought the car was really, really fun to drive. I watched the cars ahead, there was good battling back and forth. So far, so good. It may seem different, but in my position, I thought it was great,” said Hamilton.

“It created a lot of action in the first few laps of the race, so I think, you know, on this kind of track there will be a lot of action, in some other track maybe a bit less. But I think today was much better than what we all anticipated, so I think, yeah we need to just wait a few more races before actually commenting on this new regulation,” said Antonelli.

“Maybe now, there’s a bit more of a strategic mind behind every move you make, because every boost button activation, you know you’re going to pay the price big time after that, and so you always try and think multiple steps ahead to try and end up eventually first. But it’s a different way to go about racing for sure,” Leclerc said.

“Everyone’s very quick to criticize things. You need to give it a shot, you know. We’re 22 drivers, when we’ve had the best cars and the least tire degradation, and we’ve been happiest, everyone moans the racing [is] rubbish. Now, drivers aren’t perfectly happy, and everyone said it was an amazing race. So, you can’t have it all. And I think we should give it a chance and see after a few more races,” said Russell.

Outside the top four, the verdict was less impressed—Verstappen in particular. And I noted with interest a press release this morning from Red Bull that his GT3 team announced that the four-time F1 champion will contest the 2026 Nurburgring 24-hour race in May, plus the qualifying races that lead up to it. Verstappen will race alongside Jules Gounon, Dani Juncadella, and Lucas Auer in a Mercedes-AMG GT3 after securing his permit to race at the fearsome German circuit last year. With little left to prove in F1, there is absolutely a greater than zero chance the Dutch driver walks away from single-seaters next year—at least until the next F1 rule change—to try and win endurance races like Le Mans.

Red Bull had someone BASE jump into this cooling tower to unveil the livery on Verstappen’s GT3 car. Credit: Mihai Stetcu / Red Bull Content Pool

But that will surely depend on how well things go over the next few races, the next of which takes place next weekend in Shanghai, China. For now, I’m cautiously optimistic. The first few races of the season are on tracks that won’t play to these hybrids’ strengths, and it’s easy to reflexively hate anything new. But the racing on Sunday was more than entertaining enough, even if it wasn’t quite the same as we saw last year.

2026 Australian Grand Prix: Formula 1 debuts a new style of racing Read More »