Blast from the past: 15 movie gems of 1985

Beyond the blockbusters: This watch list has something for everyone over the long holiday weekend.

Peruse a list of films released in 1985 and you’ll notice a surprisingly high number of movies that have become classics in the ensuing 40 years. Sure, there were blockbusters like Back to the Future, The Goonies, Pale Rider, The Breakfast Club and Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome, but there were also critical arthouse favorites like Kiss of the Spider Woman and Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece, Ran. Since we’re going into a long Thanksgiving weekend, I’ve made a list, in alphabetical order, of some of the quirkier gems from 1985 that have stood the test of time. (Some of the films first premiered at film festivals or in smaller international markets in 1984, but they were released in the US in 1985.)

(Some spoilers below but no major reveals.)

After Hours

Credit: Warner Bros.

Have you ever had a dream, bordering on a nightmare, where you were trying desperately to get back home but obstacle after obstacle kept getting in your way? Martin Scorsese’s After Hours is the cinematic embodiment of that anxiety-inducing dreamscape. Griffin Dunne stars as a nebbishy computer data entry worker named Paul, who meets a young woman named Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) and heads off to SoHo after work to meet her. The trouble begins when his $20 cab fare blows out the window en route. The date goes badly, and Paul leaves, enduring a string of increasingly strange encounters as he tries to get back to his uptown stomping grounds.

After Hours is an unlikely mix of screwball comedy and film noir, and it’s to Scorsese’s great credit that the film strikes the right tonal balance, given that it goes to some pretty bizarre and occasionally dark places. The film only grossed about $10 million at the box office but received critical praise, and it’s continued to win new fans ever since, even inspiring an episode of Ted Lasso. It might not rank among Scorsese’s masterworks, but it’s certainly among the director’s most original efforts.

Blood Simple

Credit: Circle Films

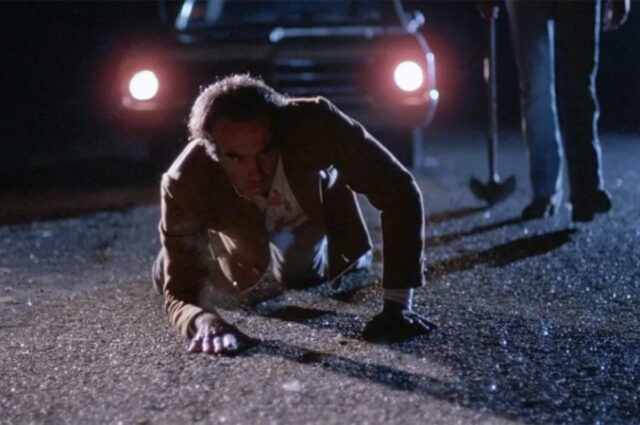

Joel and Ethan Coen are justly considered among today’s foremost filmmakers; they’ve made some of my favorite films of all time. And it all started with Blood Simple, the duo’s directorial debut, a neo-noir crime thriller set in small-town Texas. Housewife Abby (Frances McDormand) is having an affair with a bartender named Ray (John Getz). Her abusive husband, Julian (Dan Hedaya), has hired a private investigator named Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) and finds out about the affair. He then asks Visser to kill the couple for $10,000. Alas, things do not go as planned as everyone tries to outsmart everyone else, with disastrous consequences.

Blood Simple has all the elements that would become trademarks of the Coen brothers’ distinctive style: it’s both brutally violent and acerbically funny, with low-key gallows humor, not to mention inventive camerawork and lighting. The Coens accomplished a lot with their $1.5 million production budget. And you can’t beat that cast. (It was McDormand’s first feature role; she would go on to win her first Oscar for her performance in 1996’s Fargo.) The menacing shot of Ray dragging a shovel across the pavement toward a badly wounded Julian crawling on the road, illuminated by a car’s headlights, is one for the ages.

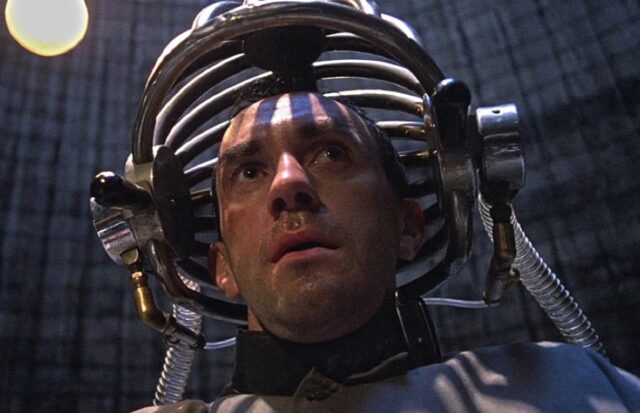

Brazil

Credit: Universal Pictures

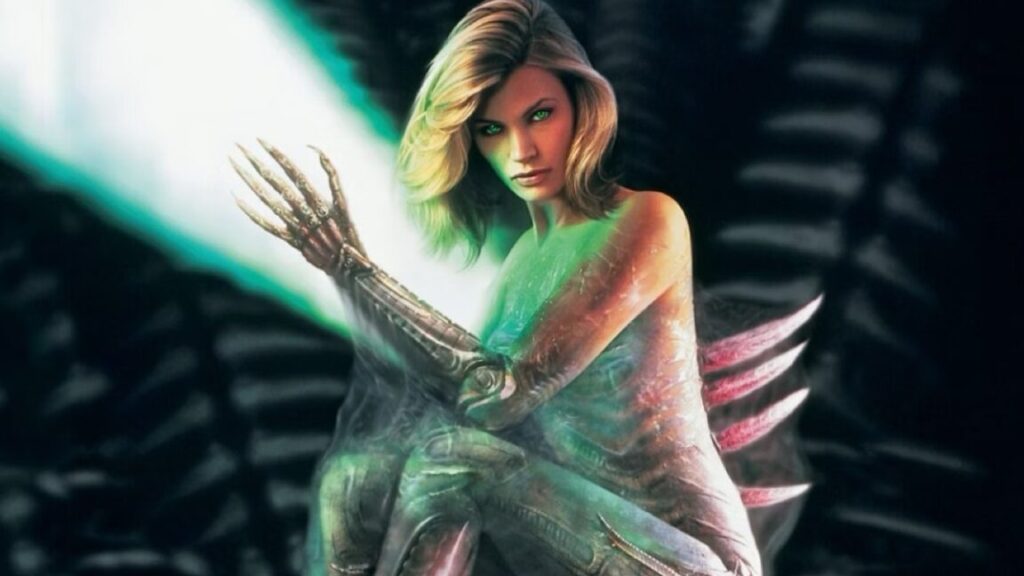

Terry Gilliam’s Oscar-nominated, Orwellian sci-fi tragicomedy, Brazil, is part of what the director has called his “Trilogy of Imagination,” along with 1981’s Time Bandits and 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Jonathan Pryce stars as a low-ranking bureaucrat named Sam Lowry who combats the soul-crushing reality of his bleak existence with elaborate daydreams in which he is a winged warrior saving a beautiful damsel in distress. One day, a bureaucratic error confuses Sam with a wanted terrorist named Archibald Tuttle (Robert De Niro), setting off a darkly comic series of misadventures as Sam tries to prove his true identity (and innocence). That’s when he meets Jill (Kim Greist), a dead ringer for his dream woman.

Along with 12 Monkeys and Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Brazil represents Gilliam at his best, yet it was almost not released in the US because Gilliam refused the studio’s request to give the film a happy ending. Each side actually ran ads in Hollywood trades presenting their respective arguments, and Gilliam ultimately prevailed. The film has since become a critical favorite and an essential must-watch for Gilliam fans. Special shoutout to Katherine Helmond’s inspired supporting performance as Sam’s mother Ida and her addiction to bad plastic surgery (“It’s just a little complication….”).

Clue

Credit: Paramount Pictures

Benoit Blanc may hate the game Clue, but it’s delighted people of all ages for generations. And so has the deliciously farcical film adaptation featuring an all-star cast. Writer/director Jonathan Lynn (My Cousin Vinny) does a great job fleshing out the game’s premise and characters. A group of people is invited to an isolated mansion for a dinner with “Mr. Boddy” (Lee Ving) and are greeted by the butler, Wadsworth (Tim Curry). There is Mrs. Peacock (Eileen Brennan), Mrs. White (Madeline Kahn), Professor Plum (Christopher Lloyd), Mr. Green (Michael McKean), Colonel Mustard (Martin Mull), and Miss Scarlet (Lesley Ann Warren).

After dinner, Mr. Boddy reveals that he is the one who has been blackmailing them all, and when the lights suddenly go out, he is murdered. As everyone frantically tries to figure out whodunnit, more bodies begin to pile up, culminating in three different endings. (A different ending was shown in each theater but now all three are included.) The script is packed with bad puns and slapstick scenarios, delivered with impeccable comic timing by the gifted cast. And who could forget Kahn’s famous ad-libbed line: “Flames… on the side of my face“? Like several films on this list, Clue got mixed reviews and bombed at the box office, but found its audience in subsequent decades. It’s now another cult classic that holds up even after multiple rewatchings.

The Company of Wolves

Credit: ITC Entertainment

Director Neil Jordan’s sumptuous Gothic fantasy horror is a haunting twist on “Little Red Riding Hood” adapted from a short story by Angela Carter in her anthology of fairy-tale reinventions, The Bloody Chamber. The central narrative concerns a young girl named Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson) who sports a knitted red cape and encounters a rakish huntsman/werewolf (Micha Bergese) in the woods en route to her grandmother’s (Angela Lansbury) house. There are also several embedded wolf-centric fairy tales, two told by Rosaleen and two told by the grandmother.

Jordan has described this structure as “a story with very different movements,” all variations on the central theme and “building to the fairy tale that everybody knows.” The production design and gorgeously sensual cinematography—all achieved on a limited $2 million budget—further enhance the dreamlike atmosphere. The Company of Wolves, like the fairy tale that inspired it, is an unapologetically Freudian metaphor for Rosaleen’s romantic and sexual awakening, in which she discovers her own power, which both frightens and fascinates her. It’s rare to find such a richly layered film rife with symbolism and brooding imagery.

Desperately Seeking Susan

Credit: Orion Pictures

In this quintessential 1980s screwball comedy about mistaken identity, Roberta (Rosanna Arquette) is a dissatisfied upper-class New Jersey housewife fascinated by the local tabloid personal ads, especially messages between two free-spirited bohemian lovers, Susan (Madonna) and Jim (Robert Joy). She follows Susan one day and is conked on the head when a mob enforcer mistakes her for Susan, who had stolen a pair of valuable earrings from another paramour, who had stolen them from a mobster in turn. Roberta comes to with amnesia and, believing herself to be Susan, is befriended by Jim’s best friend, Dez (Aidan Quinn).

Desperately Seeking Susan is director Susan Seidelman’s love letter to the (admittedly sanitized) 1980s counterculture of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, peppered with cameo appearances by performance artists, musicians, comedians, actors, painters, and so forth of that time period. The script is rife with witty one-liners and a stellar supporting cast, including John Turturro as the owner of a seedy Magic Club, Laurie Metcalf as Roberta’s sister-in-law Leslie, and a deadpan Steven Wright as Leslie’s dentist love interest. It’s breezy, infectious, frothy fun, and easily Madonna’s best acting role, perhaps because she is largely playing herself.

Dreamchild

Credit: Thorn EMI

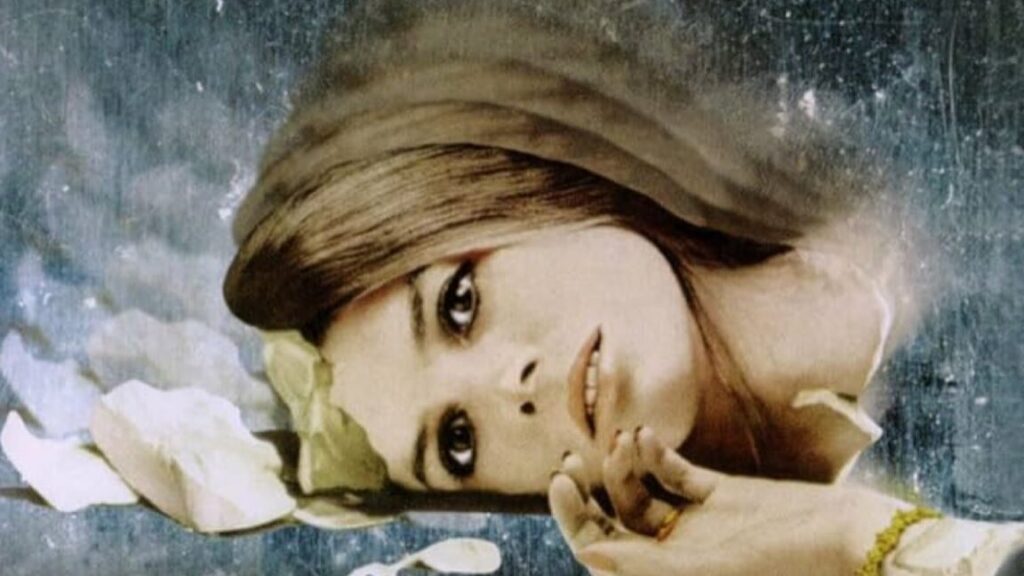

Dennis Potter (The Singing Detective) co-wrote the screenplay for this beautifully shot film about Alice Liddell, the 11-year-old girl who inspired Alice in Wonderland. Coral Browne plays the elderly widowed Alice, who travels by ship to the US to receive an honorary degree in celebration of Lewis Carroll’s birthday—a historical event. From there, things become entirely fictional, as Alice must navigate tabloid journalists, a bewildering modern world, and various commercial endorsement offers that emerge because of Alice’s newfound celebrity.

All the while, Alice struggles to process resurfaced memories—told via flashbacks and several fantasy sequences featuring puppet denizens of Wonderland—about her complicated childhood friendship with “Mr. Dodgson” (Ian Holm) and the conflicting emotions that emerge. (Amelia Shankley plays Alice as a child.) Also, romance blooms between Alice’s companion, an orphan named Lucy (Nicola Cowper), and Alice’s new US agent, Jack Dolan (Peter Gallagher).

Directed by Gavin Millar, Dreamchild taps into the ongoing controversy about Carroll’s fascination, as a pioneer of early photography, with photographing little girls in the nude (a fairly common practice in Victorian times). There is no evidence he photographed Alice Liddell in this way, however, and Potter himself told The New York Times in 1985 that he didn’t believe there was ever any improper behavior. Repressed romantic longing is what is depicted in Dreamchild, and it’s to Millar’s credit, as well as Holm’s and Browne’s nuanced performances, that the resulting film is heartbreakingly bittersweet rather than squicky.

Fandango

Credit: Warner Bros.

Director Kevin Reynolds’ Fandango started out as a student film satirizing fraternity life at a Texas university. Steven Spielberg thought the effort was promising enough to fund a full-length feature. Set in 1971, the plot (such that it is) centers on five college seniors—the Groovers—who embark on a road trip to celebrate graduation. Their misadventures include running out of gas, an ill-advised parachuting lesson, and camping on the abandoned set of Giant, but it’s really about the group coming to terms with the harsh realities of adulthood that await, particularly since they’ve all been called up for the Vietnam draft.

Spielberg purportedly was unhappy with the final film, but it won over other fans (like Quentin Tarantino) and became a sleeper hit, particularly after its home video release. The humor is dry and quirky, and Reynolds has a knack for sight gags and the cadences of local dialect. Sure, the plot meanders in a rather quixotic fashion, but that’s part of the charm. And the young cast is relentlessly likable. Fandango featured Kevin Costner in his first starring role, and Reynolds went on to make several more films with Costner (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Rapa Nui, Waterworld), with mixed success. But Fandango is arguably his most enduring work.

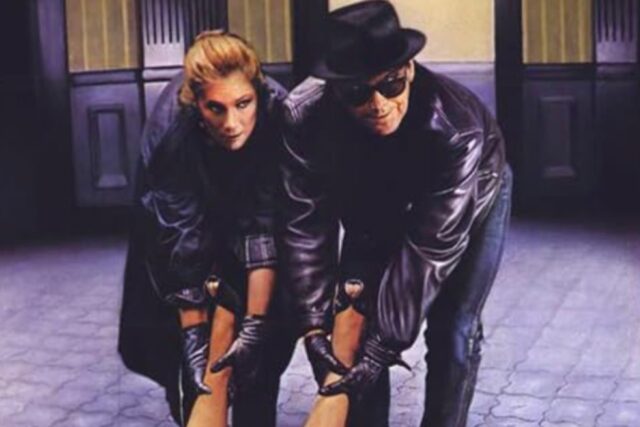

Ladyhawke

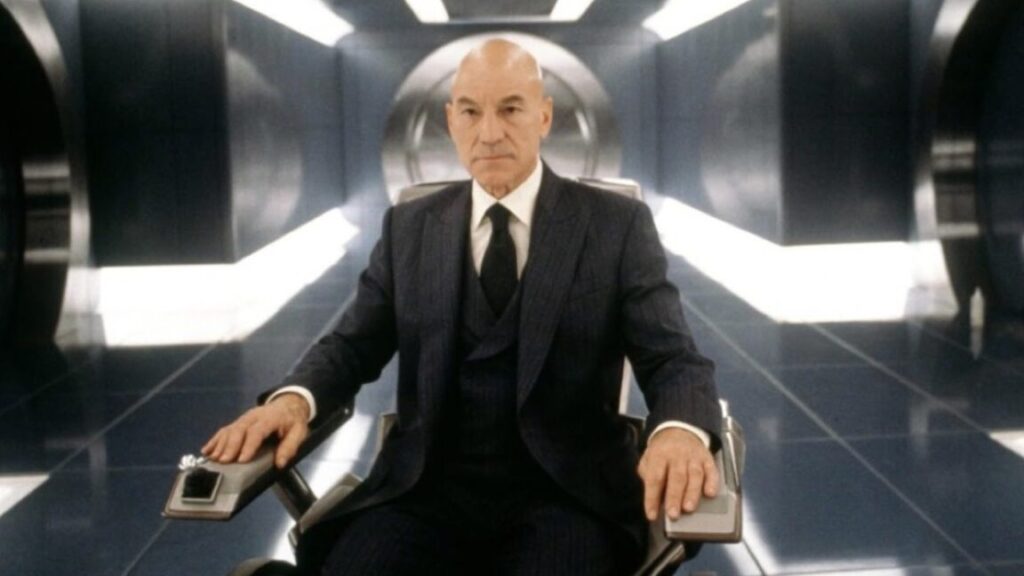

Credit: Warner Bros.

Rutger Hauer and Michelle Pfeiffer star in director Richard Donner’s medieval fantasy film, playing a warrior named Navarre and his true love Isabeau who are cursed to be “always together, yet eternally apart.” She is a hawk by day, while he is a wolf by night, and the two cannot meet in their human forms, due to the jealous machinations of the evil Bishop of Aquila (John Wood), once spurned by Isabeau. Enter a young thief named Philippe Gaston (Matthew Broderick), who decides to help the couple lift the curse and exact justice on the bishop and his henchmen.

Ladyhawke only grossed $18.4 million at the box office, just shy of breaking even against its $20 million budget, and contemporary critical reviews were very much mixed, although the film got two Oscar nods for best sound and sound effects editing. Sure, the dialogue is occasionally clunky, and Broderick’s wisecracking role is a bit anachronistic (shades of A Knight’s Tale). But the visuals are stunning, and the central fairy tale—fueled by Hauer’s and Pfeiffer’s performances—succeeds in capturing the imagination and holds up very well as a rewatch.

Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure

Credit: Warner Bros.

Paul Reubens originally created the Pee-Wee Herman persona for the Groundlings sketch comedy theater in Los Angeles, and his performances eventually snagged him an HBO special in 1981. That, in turn, led to Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, directed by Tim Burton (who makes a cameo as a street thug), in which the character goes on a madcap quest to find his stolen bicycle. The quest takes Pee-Wee to a phony psychic, a tacky roadside diner, the Alamo Museum in San Antonio, Texas, a rodeo, and a biker bar, where he dances in platform shoes to “Tequila.” But really, it’s all about the friends he makes along the way, like the ghostly trucker Large Marge (Alice Nunn).

Some have described the film as a parodic homage to the classic Italian film, Bicycle Thieves, but tonally, Reubens wanted something more akin to the naive innocence of Pollyanna (1960). He chose Burton to direct after seeing the latter’s 1984 featurette, Frankenweenie, because he liked Burton’s visual sensibility. Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure is basically a surreal live-action cartoon, and while contemporary critics were divided—it’s true that a little Pee-Wee goes a long way and the over-the-top silliness is not to everyone’s taste—the film’s reputation and devoted fandom have grown over the decades.

A Private Function

Credit: HandMade Films

A Private Function is an homage of sorts to the British post-war black comedies produced by Ealing Studios between 1947 and 1957, including such timeless classics as Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Lavender Hill Mob, and The Ladykillers. It’s set in a small Yorkshire town in 1947, as residents struggle to make ends meet amid strict government rations. With the pending royal wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, the wealthier townsfolk decide to raise a pig (illegally) to celebrate with a feast.

Those plans are put in jeopardy when local chiropodist Gilbert Chivers (Michael Palin) and his perennially discontented wife Joyce (Maggie Smith) steal the pig. Neither Gilbert nor Joyce knows the first thing about butchering said pig (named Betty), but she assures her husband that “Pork is power!” And of course, everyone must evade the local food inspector (Bill Paterson), intent on enforcing the rationing regulations. The cast is a veritable who’s who of British character actors, all of whom handle the absurd situations and often scatalogical humor with understated aplomb.

Prizzi’s Honor

Credit: 20th Century Fox

The great John Huston directed this darkly cynical black comedy. Charley Partanna (Jack Nicholson) is a Mafia hitman for the Prizzi family in New York City who falls for a beautiful Polish woman named Irene (Kathleen Turner) at a wedding. Their whirlwind romance hits a snag when Charley’s latest hit turns out to be Irene’s estranged husband, who stole money from the Prizzis. That puts Charlie in a dilemma. Does he ice her? Does he marry her? When he finds out Irene is a contract killer who also does work for the mob, it looks like a match made in heaven. But their troubles are just beginning.

Turner and Nicholson have great on-screen chemistry and play it straight in outrageous circumstances, including the comic love scenes. The rest of the cast is equally game, especially William Hickey as the aged Don Corrado Prizzi, equal parts ruthlessly calculating and affectionately paternal. “Here… have a cookie,” he offers his distraught granddaughter (and Charley’s former fiancée), Maerose (Anjelica Huston). Huston won a supporting actress Oscar for her performance, which probably made up for the fact that she was paid at scale and dismissed by producers as having “no talent,” despite—or perhaps because of—being the director’s daughter and Nicholson’s then-girlfriend. Prizzi’s Honor was nominated for eight Oscars all told, and it deserves every one of them.

The Purple Rose of Cairo

Credit: Orion Pictures

Woody Allen has made so many films that everyone’s list of favorites is bound to differ. My personal all-time favorite is a quirky, absurdist bit of metafiction called The Purple Rose of Cairo. Mia Farrow stars as Cecelia, a New Jersey waitress during the Great Depression who is married to an abusive husband (Danny Aiello). She finds escape from her bleak existence at the local cinema, watching a film (also called The Purple Rose of Cairo) over and over again. One day, the male lead, archaeologist Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels), breaks character to address Cecelia directly. He then steps out of the film and the two embark on a whirlwind romance. (“I just met a wonderful man. He’s fictional, but you can’t have everything.”)

Meanwhile, the remaining on-screen characters (who are also sentient) refuse to perform the rest of the film until Tom returns, insulting audience members to pass the time. Then the actor who plays Tom, Gil Shepherd (also Daniels), shows up to try to convince Cecilia to choose reality over her fantasy dream man come to life. Daniels is wonderful in the dual role, contrasting the cheerfully naive Tom against the jaded, calculating Gil. This clever film is by turns wickedly funny, poignant, and ultimately bittersweet, and deserves a place among Allen’s greatest works.

Real Genius

Credit: TriStar Pictures

How could I omit this perennial favorite? Its inclusion is a moral imperative. Fifteen-year-old Mitch Taylor (Gabriel Jarret) is a science genius and social outcast at his high school who is over the moon when Professor Jerry Hathaway (William Atherton), a star researcher at the fictional Pacific Technical University, handpicks Mitch to work in his own lab on a laser project. But unbeknownst to Mitch, Hathaway is in league with a covert CIA program to develop a space-based laser weapon for political assassinations. They need a 5-megawatt laser and are relying on Mitch and fellow genius/graduating senior Chris Knight (Val Kilmer) to deliver.

The film only grossed $12.9 million domestically against its $8 million budget. Reviews were mostly positive, however, and over time, it became a sleeper hit. Sure, the plot is predictable, the characters are pretty basic, and the sexually frustrated virgin nerds ogling hot cosmetology students in bikinis during the pool party reflects hopelessly outdated stereotypes on several fronts. But the film still offers smartly silly escapist fare, with a side of solid science for those who care about such things. Real Genius remains one of the most charming, winsome depictions of super-smart science whizzes idealistically hoping to change the world for the better with their work.

Witness

Credit: Paramount

Witness stars Harrison Ford as John Book, a Philadelphia detective, who befriends a young Amish boy named Samuel (Lukas Haas) and his widowed mother Rachel (Kelly McGillis) after Samuel inadvertently witnesses the murder of an undercover cop in the Philadelphia train station. When Samuel identifies one of the killers as a police lieutenant (Danny Glover), Book must go into hiding with Rachel’s Amish family to keep Samuel safe until he can find a way to prove the murder was an inside job. And he must fight his growing attraction to Rachel to boot.

This was director Peter Weir’s first American film, but it shares the theme of clashing cultures that dominated Weir’s earlier work. The lighting and scene composition were inspired by Vermeer’s paintings and enhanced the film’s quietly restrained tone, making the occasional bursts of violence all the more impactful. The film has been praised for its depiction of the Amish community, although the extras were mostly Mennonites because the local Amish did not wish to appear on film. (The Amish did work on set as carpenters and electricians, however.) Witness turned into a surprise sleeper hit for Paramount. All the performances are excellent, including Ford and McGillis as the star-crossed lovers from different worlds, but it’s the young Haas who steals every scene with his earnest innocence.

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Blast from the past: 15 movie gems of 1985 Read More »