Marine biologist for a day: Ars goes shark tagging

MIAMI—We were beginning to run out of bait, and the sharks weren’t cooperating.

Everybody aboard the Research Vessel Garvin had come to Miami for the sharks—to catch them, sample them, and tag them, all in the name of science. People who once wanted to be marine biologists, actual marine biologists, shark enthusiasts, the man who literally wrote the book Why Sharks Matter, and various friends and family had spent much of the day sending fish heads set with hooks over the side of the Garvin. But each time the line was hauled back in, it came in slack, with nothing but half-eaten bait or an empty hook at the end.

And everyone was getting nervous.

I: “No assholes”

The Garvin didn’t start out as a research vessel. Initially, it was a dive boat that took people to wrecks on the East Coast. Later, owner Hank Garvin used it to take low-income students from New York City and teach them how to dive, getting them scuba certified. But when Garvin died, his family put the boat, no longer in prime condition, on the market.

A thousand miles away in Florida, Catherine MacDonald was writing “no assholes” on a Post-it note.

At the time, MacDonald was the coordinator of a summer internship program at the University of Miami, where she was a PhD student. And even at that stage in her career, she and her colleagues had figured out that scientific field work had a problem.

“Science in general does not have a great reputation of being welcoming and supportive and inclusive and kind,” said David Shiffman, author of the aforementioned book and a grad school friend of MacDonald’s. “Field science is perhaps more of a problem than that. And field science involving what are called charismatic megafauna, the big animals that everyone loves, is perhaps worse than that. It’s probably because a lot of people want to do this, which means if we treat someone poorly and they quit, it’s not going to be long before someone else wants to fill the spot.”

MacDonald and some of her colleagues—Christian Pankow, Jake Jerome, Nick Perni, and Julia Wester (a lab manager and some fellow grad students at the time)—were already doing their best to work against these tendencies at Miami and help people learn how to do field work in a supportive environment. “I don’t think that you can scream abuse at students all day long and go home and publish great science,” she said, “because I don’t think that the science itself escapes the process through which it was generated.”

So they started to think about how they might extend that to the wider ocean science community. The “no assholes” Post-it became a bit of a mission statement, one that MacDonald says now sits in a frame in her office. “We decided out the gate that the point of doing this in part was to make marine science more inclusive and accessible and that if we couldn’t do that and be a successful business, then we were just going to fail,” she told Ars. “That’s kind of the plan.”

But to do it properly, they needed a boat. And that meant they needed money. “We borrowed from our friends and family,” MacDonald said. “I took out a loan on my house. It was just our money and all of the money that people who loved us were willing to sink into the project.”

Even that might not have been quite enough to afford a badly run-down boat. But the team made a personal appeal to Hank Garvin’s family. “They told the family who was trying to offload the boat, ‘Maybe someone else can pay you more for it, but here’s what we’re going to use it for, and also we’ll name the boat after your dad,'” Shiffman said. “And they got it.”

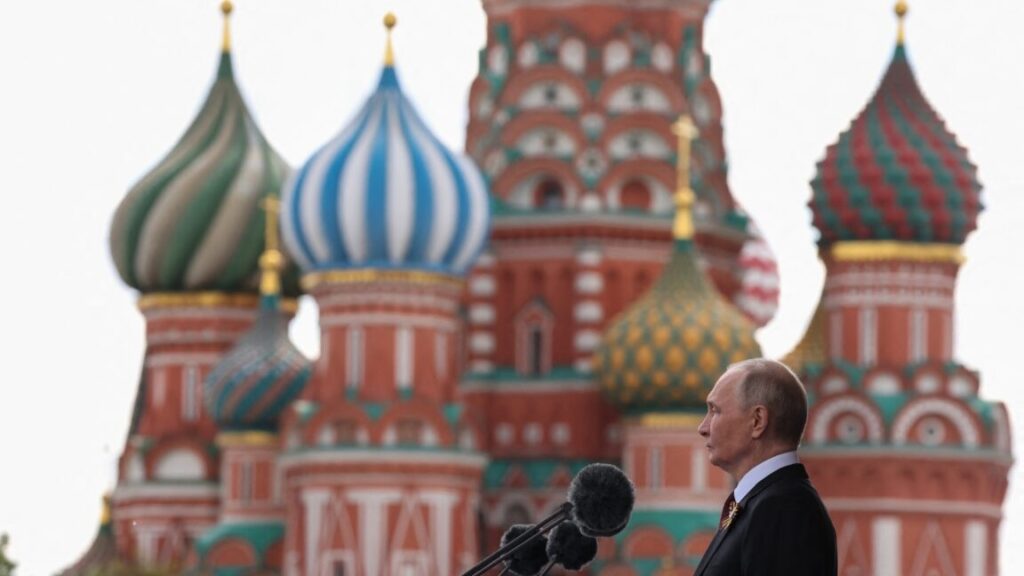

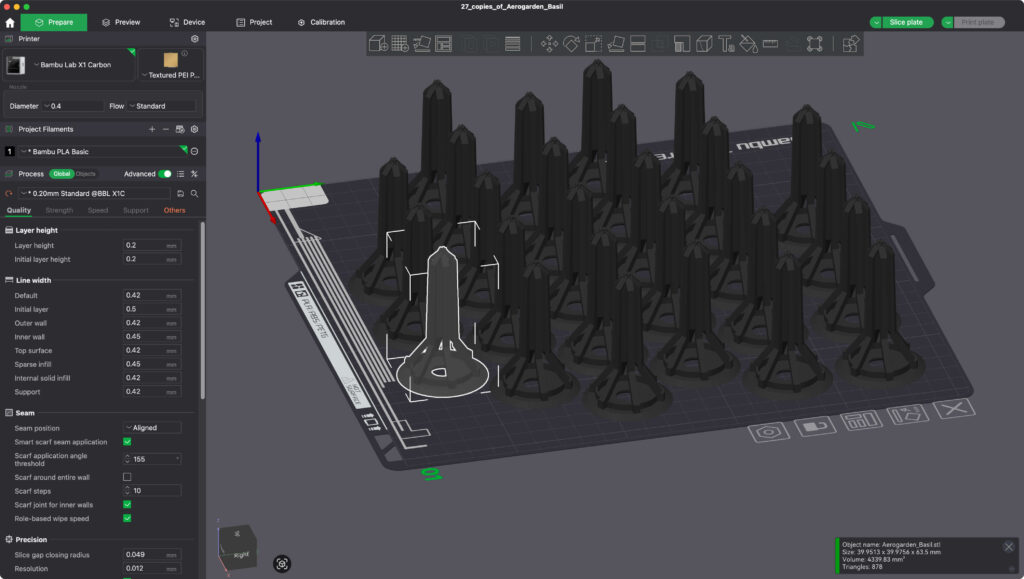

For the day, everybody who signed up had the chance to do most of the work that scientists normally would. Julia Saltzman

But it wasn’t enough to launch what would become the Field School. The Garvin was in good enough shape to navigate to Florida, but it needed considerable work before it could receive all the Coast Guard certifications required to get a Research Vessel designation. And given the team’s budget, that mostly meant the people launching the Field School had to learn to do the work themselves.

“One of [co-founder] Julia’s good friends was a boat surveyor, and he introduced us to a bunch of people who taught us skills or introduced us to someone else who could fix the alignment of our propellers or could suggest this great place in Louisiana that we could send the transmissions for rebuilding or could help us figure out which paints to use,” MacDonald said.

“We like to joke that we are the best PhD-holding fiberglassers in Miami,” she told Ars. “I don’t actually know if that’s true. I couldn’t prove it. But we just kind of jumped off the cliff together in terms of trying to make it work. Although we certainly had to hire folks to help us with a variety of projects, including building a new fuel tank because we are not the best PhD-holding welders in Miami for certain.”

II: Fishing for sharks

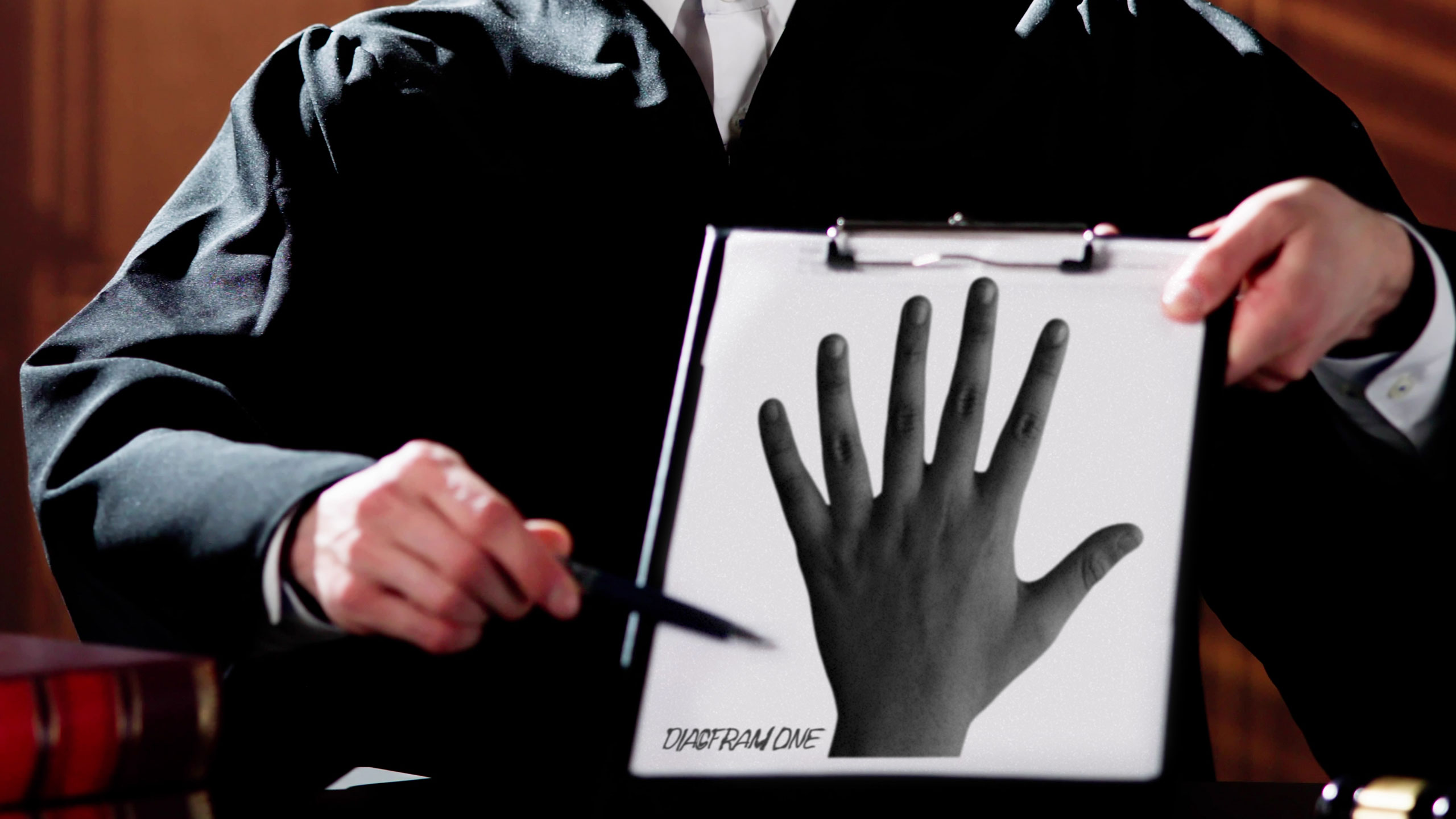

On the now fully refurbished Garvin, we were doing drum-line fishing. This involved a 16 kg (35-pound) weight connected to some floats by an extremely thick piece of rope. Also linked to the weight was a significant amount of 800-pound test line (meaning a monofilament polymer that won’t snap until something exerts over 800 lbs/360 kg of force on it) with a hook at the end. Most species of sharks need to keep swimming to force water over their gills or else suffocate; the length of the line allows them to swim in circles around the weight. The hook is also shaped to minimize damage to the fish during removal.

To draw sharks to the drum line, each of the floats had a small metal cage to hold chunks of fish that would release odorants. A much larger piece—either a head or cross-section of the trunk of a roughly foot-long fish—was set on the hook.

Deploying all of this was where the Garvin‘s passengers, none of whom had field research experience, came in. Under the tutelage of the people from the Field School, we’d lower the drum from a platform at the stern of the Garvin to the floor of Biscayne Bay, within sight of Miami’s high rises. A second shark enthusiast would send the float overboard as the Garvin‘s crew logged its GPS coordinates. After that, it was simply a matter of gently releasing the monofilament line from a large hand-held spool.

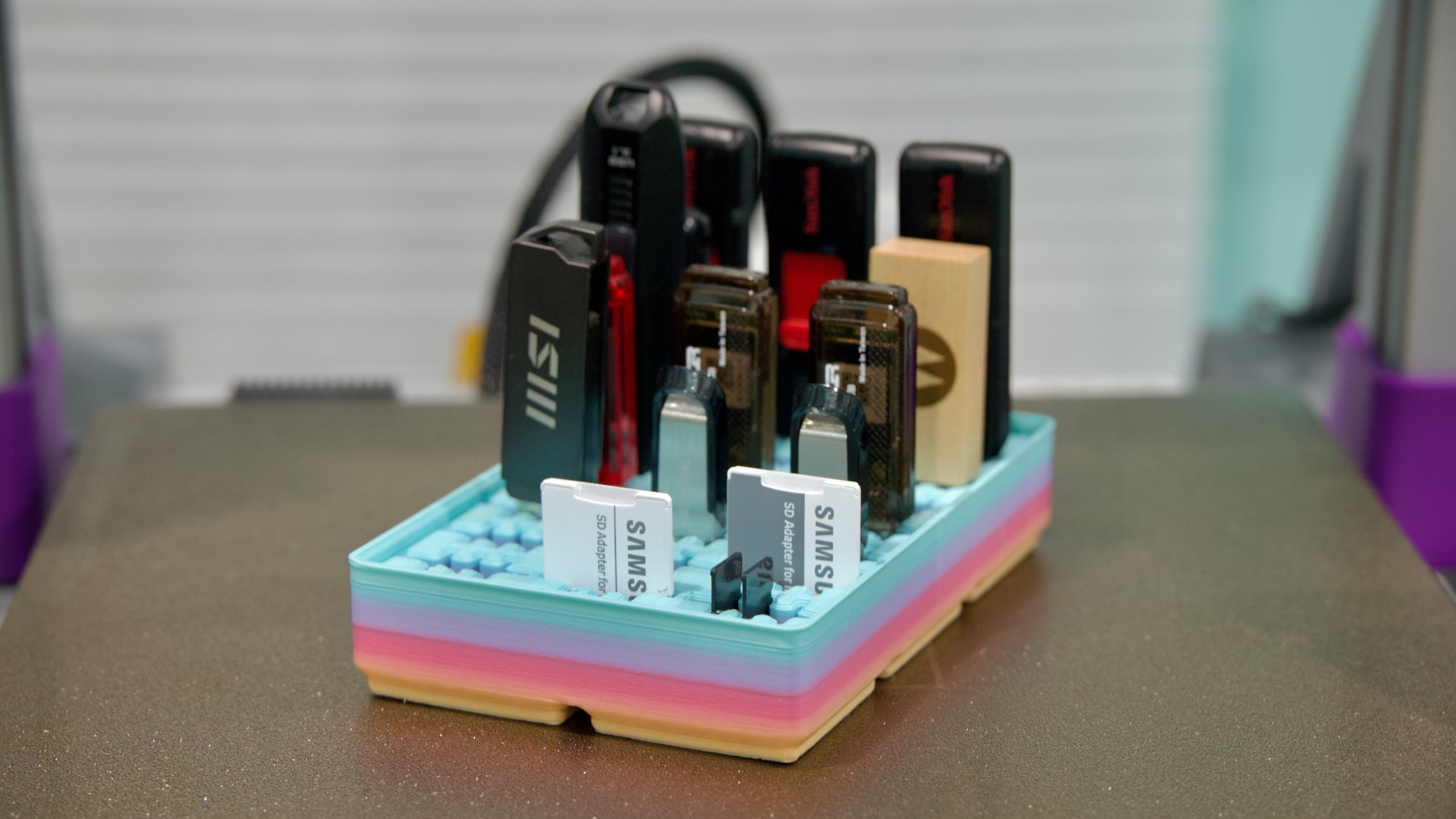

From right to left, the floats, the weight, and the bait all had to go into the water through an organized process. Julia Saltzman

One by one, we set 10 drums in a long row near one of the exits from Biscayne Bay. With the last one set, we went back to the first and reversed the process: haul in the float, use the rope to pull in the drum, and then let a Field School student test whether the line had a shark at the end. If not, it and the spool were handed over to a passenger, accompanied by tips on how to avoid losing fingers if a shark goes after the bait while being pulled back in.

Rebait, redeploy, and move on. We went down the line of 10 drums once, then twice, then thrice, and the morning gave way to afternoon. The routine became far less exciting, and getting volunteers for each of the roles in the process seemed to require a little more prodding. Conversations among the passengers and Field School people started to become the focus, the fishing a distraction, and people starting giving the bait buckets nervous looks.

And then, suddenly, a line went tight while it was being hauled in, and a large brown shape started moving near the surface in the distance.

III: Field support

Mortgaging your home is not a long-term funding solution, so over time, the Field School has developed a bit of a mixed model. Most of the people who come to learn there pay the costs for their time on the Garvin. That includes some people who sign up for one of the formal training programs. Shiffman also uses them to give undergraduates in the courses he teaches some exposure to actual research work.

“Over spring break this year, Georgetown undergrads flew down to Miami with me and spent a week living on Garvin, and we did some of what you saw,” he told Ars. “But also mangrove, snorkeling, using research drones, and going to the Everglades—things like that.” They also do one-day outings with some local high schools.

Many of the school’s costs, however, are covered by groups that pay to get the experience of being an ocean scientist for a day. These have included everything from local Greenpeace chapters to companies signing up for a teamwork-building experience. “The fundraiser rate [they pay] factors in not only the cost of taking those people out but also the cost of taking a low-income school group out in the future at no cost,” Shiffman said.

And then there are groups like the one I was joining—paying the fundraiser rate but composed of random collections of people brought together by little more than meeting Shiffman, either in person or online. In these cases, the Garvin is filled with a combination of small groups nucleated by one shark fan or people who wanted to be a marine biologist at some point or those who simply have a general interest in science. They’ll then recruit one or more friends or family members to join them, with varying degrees of willingness.

For a day, they all get to contribute to research. A lot of what we know about most fish populations comes from the fishing industry. And that information is often biased by commercial considerations, changing regulations, and more. The Field School trips, by contrast, give an unbiased sampling of whatever goes for its bait.

“The hardest part about marine biology research is getting to the animals—it’s boat time,” Shiffman said. “And since they’re already doing that, often in the context of teaching people how to do field skills, they reached out to colleagues all over the place and said, ‘Hey, here’s where we’re going. Here’s what we’re doing, here’s what we’re catching. Can we get any samples for you?’ So they’re taking all kinds of biological samples from the animals, and depending on what we catch, it can be for up to 15 different projects, with collaborators all over the country.”

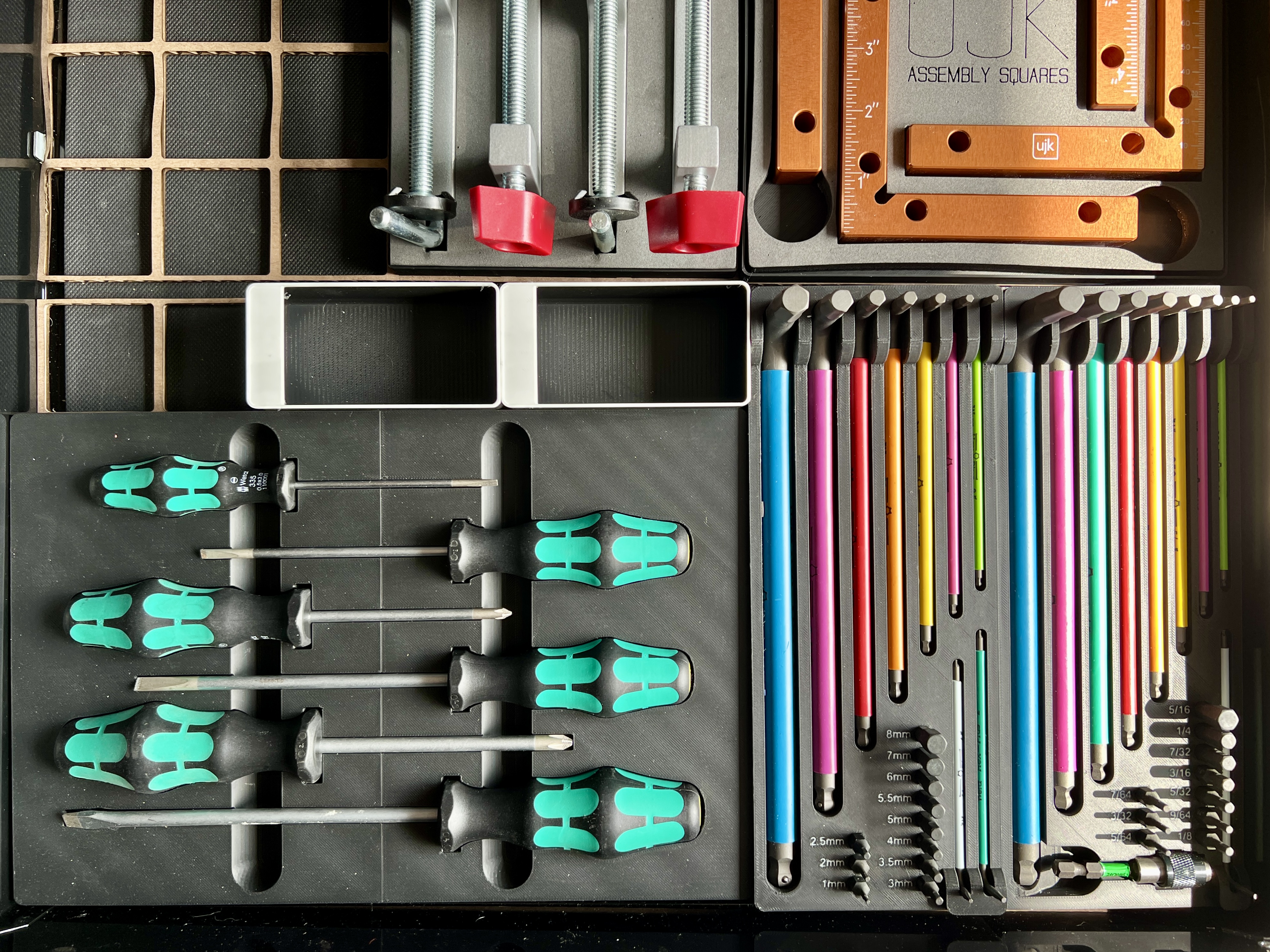

And taking those samples is the passengers’ job. So shortly after leaving the marina on Garvin, we were divided up into teams and told what our roles would be once a shark was on board. One team member would take basic measurements of the shark’s dimensions. A second would scan the shark for parasites and place them in a sample jar, while another would snip a small piece of fin off to get a DNA sample. Finally, someone would insert a small tag at the base of the shark’s dorsal fin using a tool similar to a hollow awl. Amid all that, one of the Field School staff members would use a syringe to get a blood sample.

All of this would happen while members of the Field School staff were holding the shark in place—larger ones on a platform at the stern of the Garvin, smaller ones brought on board. The staff were the only ones who were supposed to get close to what Shiffman referred to as “the bitey end” of the shark. For most species, this would involve inserting one of three different-sized PVC tubes (for different-sized sharks) that seawater would be pumped through to keep the shark breathing and give them something to chomp down on. Other staff members held down the “slappy end.”

For a long time, all of this choreography seemed abstract. But there was finally a shark on the other end of the line, slowly being hauled toward the boat.

IV: Pure muscle and rage?

The size and brown color were an immediate tip-off to those in the know: We had a nurse shark, one that Shiffman described as being “pure muscle and rage.” Despite that, a single person was able to haul it in using a hand spool. Once restrained, the shark largely remained a passive participant in what came next. Nurse sharks are one of the few species that can force water over their gills even when stationary, and the shark’s size—it would turn out to be over 2 meters long—meant that it would need to stay partly submerged on the platform in the back.

So one by one, the first team splashed onto the platform and got to work. Despite their extremely limited training, it took just over five minutes for them to finish the measurements and get all the samples they needed. Details like the time, location, and basic measurements were all logged by hand on paper, although the data would be transferred to a spreadsheet once it was back on land. And the blood sample had some preliminary work done on the Garvin itself, which was equipped with a small centrifuge. All of that data would eventually be sent off to many of the Field School’s collaborators.

Shark number two, a blacktip, being hauled to the Garvin. Julia Saltzman

Since the shark was showing no signs of distress, all the other teams were allowed to step onto the platform and pet it, partly due to the fear that this would be the only one we caught that day. Sharks have a skin that’s smooth in one direction but rough if stroked in the opposite orientation, and their cartilaginous skeleton isn’t as solid as the bone most other vertebrates rely on. It was very much not like touching any other fish I’d encountered.

After we had all literally gotten our feet wet, the shark, now bearing the label UM00229, was sent on its way, and we went back to checking the drum lines.

A short time later, we hauled in a meter-long blacktip shark. This time, we set it up on an ice chest on the back of the boat, with a PVC tube firmly inserted into its mouth. Again, once the Field School staff restrained the shark, the team of amateurs got to work quickly and efficiently, with the only mishap being a person who rubbed their fingers the wrong way against the shark skin and got an abrasion that drew a bit of blood. Next up would be team three, the final group—and the one I was a part of.

V: The culture beyond science

I’m probably the perfect audience for an outing like this. Raised on a steady diet of Jacques Cousteau documentaries, I was also drawn to the idea of marine biology at one point. And having spent many of my years in molecular biology labs, I found myself jealous of the amazing things the field workers I’d met had experienced. The idea of playing shark scientist for a day definitely appealed to me.

Once processed, the sharks seemed content to get back to the business of being a shark. Credit: Julia Saltzman

But I probably came away as impressed by the motivation behind the Field School as I was with the sharks. I’ve been in science long enough to see multiple examples of the sort of toxic behaviors that the school’s founders wanted to avoid, and I wondered how science would ever change when there’s no obvious incentive for anyone to improve their behavior. In the absence of those incentives, MacDonald’s idea is to provide an example of better behavior—and that might be the best option.

“Overall, the thing that I really wanted at the end of the day was for people to look at some of the worst things about the culture of science and say, ‘It doesn’t have to be like that,'” she told Ars.

And that, she argues, may have an impact that extends well beyond science. “It’s not just about training future scientists, it’s about training future people,” she said. “When science and science education hurts people, it affects our whole society—it’s not that it doesn’t matter to the culture of science, because it profoundly does, but it matters more broadly than that as well.”

With motivations like that, it would have felt small to be upset that my career as a shark tagger ended up in the realm of unfulfilled potential, since I was on tagging team three, and we never hooked shark number three. Still, I can’t say I wasn’t a bit annoyed when I bumped into Shiffman a few weeks later, and he gleefully informed me they caught 14 of them the day after.

If you have a large enough group, you can support the Field School by chartering the Garvin for an outing. For smaller groups, you need to get in touch with David Shiffman.

Listing image: Julia Saltzman

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Marine biologist for a day: Ars goes shark tagging Read More »