How close are we to solid state batteries for electric vehicles?

Superionic materials promise greater range, faster charges and more safety.

In early 2025, Mercedes-Benz ran its first road tests of an electric passenger car powered by a prototype solid-state battery pack. The carmaker predicts the next-gen battery will increase the electric vehicle’s driving range to over 620 miles (1,000 kilometers). Credit: Mercedes-Benz Group

Every few weeks, it seems, yet another lab proclaims yet another breakthrough in the race to perfect solid-state batteries: next-generation power packs that promise to give us electric vehicles (EVs) so problem-free that we’ll have no reason left to buy gas-guzzlers.

These new solid-state cells are designed to be lighter and more compact than the lithium-ion batteries used in today’s EVs. They should also be much safer, with nothing inside that can burn like those rare but hard-to-extinguish lithium-ion fires. They should hold a lot more energy, turning range anxiety into a distant memory with consumer EVs able to go four, five, six hundred miles on a single charge.

And forget about those “fast” recharges lasting half an hour or more: Solid-state batteries promise EV fill-ups in minutes—almost as fast as any standard car gets with gasoline.

This may all sound too good to be true—and it is, if you’re looking to buy a solid-state-powered EV this year or next. Look a bit further, though, and the promises start to sound more plausible. “If you look at what people are putting out as a road map from industry, they say they are going to try for actual prototype solid-state battery demonstrations in their vehicles by 2027 and try to do large-scale commercialization by 2030,” says University of Washington materials scientist Jun Liu, who directs a university-government-industry battery development collaboration known as the Innovation Center for Battery500 Consortium.

Indeed, the challenge is no longer to prove that solid-state batteries are feasible. That has long since been done in any number of labs around the world. The big challenge now is figuring out how to manufacture these devices at scale, and at an acceptable cost.

Superionic materials to the rescue

Not so long ago, says Eric McCalla, who studies battery materials at McGill University in Montreal and is a coauthor of a paper on battery technology in the 2025 Annual Review of Materials Research, this heady rate of advancement toward powering electric vehicles was almost unimaginable.

Until about 2010, explains McCalla, “the solid-state battery had always seemed like something that would be really awesome—if we could get it to work.” Like current EV batteries, it would still be built with lithium, an unbeatable element when it comes to the amount of charge it can store per gram. But standard lithium-ion batteries use a liquid, a highly flammable one at that, to allow easy passage of charged particles (ions) between the device’s positive and negative electrodes. The new battery design would replace the liquid with a solid electrolyte that would be nearly impervious to fire—while allowing for a host of other physical and chemical changes that could make the battery faster charging, lighter in weight, and all the rest.

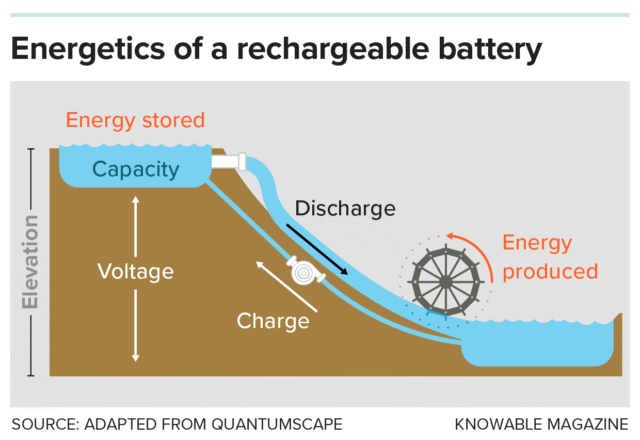

“But the material requirements for these solid electrolytes were beyond the state of the art,” says McCalla. After all, standard lithium-ion batteries have a good reason for using a liquid electrolyte: It gives the ionized lithium atoms inside a fluid medium to move through as they shuttle between the battery’s two electrodes. This back-and-forth cycle is how any battery stores and releases energy—the chemical equivalent of pumping water from a low-lying reservoir to a high mountain lake, then letting it run back down through a turbine whenever you need some power. This hypothetical new battery would somehow have to let those lithium ions flow just as freely—but through a solid.

Storing electrical energy in a rechargeable battery is like pumping water from a low-lying reservoir up to a high mountain lake. Likewise, using that energy to power an external device is like letting the water flow back downhill through a generator. The volume of the mountain lake corresponds to the battery’s capacity, or how much charge it can hold, while the lake’s height corresponds to the battery’s voltage—how much energy it gives to each unit of charge it sends through the device.

Credit: Knowable Magazine

Storing electrical energy in a rechargeable battery is like pumping water from a low-lying reservoir up to a high mountain lake. Likewise, using that energy to power an external device is like letting the water flow back downhill through a generator. The volume of the mountain lake corresponds to the battery’s capacity, or how much charge it can hold, while the lake’s height corresponds to the battery’s voltage—how much energy it gives to each unit of charge it sends through the device. Credit: Knowable Magazine

This seemed hopeless for larger uses such as EVs, says McCalla. Certain polymers and other solids were known to let ions pass, but at rates that were orders of magnitude slower than liquid electrolytes. In the past two decades, however, researchers have discovered several families of lithium-rich compounds that are “superionic”—meaning that some atoms behave like a crystalline solid while others behave more like a liquid—and that can conduct lithium ions as fast as standard liquid electrolytes, if not faster.

“So the bottleneck suddenly is not the bottleneck anymore,” says McCalla.

True, manufacturing these batteries can be a challenge. For example, some of the superionic solids are so brittle that they require special equipment for handling, while others must be processed in ultra-low humidity chambers lest they react with water vapor and generate toxic hydrogen sulfide gas.

Still, the suddenly wide-open potential of solid-state batteries has led to a surge of research and development money from funding agencies around the globe—not to mention the launch of multiple startup companies working in partnership with carmakers such as Toyota, Volkswagen, and many more. Although not all the numbers are public, investments in solid-state battery development are already in the billions of dollars worldwide.

“Every automotive company has said solid-state batteries are the future,” says University of Maryland materials scientist Eric Wachsman. “It’s just a question of, When is that future?”

The rise of lithium-ion batteries

Perhaps the biggest reason to ask that “when” question, aside from the still-daunting manufacturing challenges, is a stark economic reality: Solid-state batteries will have to compete in the marketplace with a standard lithium-ion industry that has an enormous head start.

“Lithium-ion batteries have been developed and optimized over the last 30 years, and they work really great,” says physicist Alex Louli, an engineer and spokesman at one of the leading solid-state battery startups, San Jose, California-based QuantumScape.

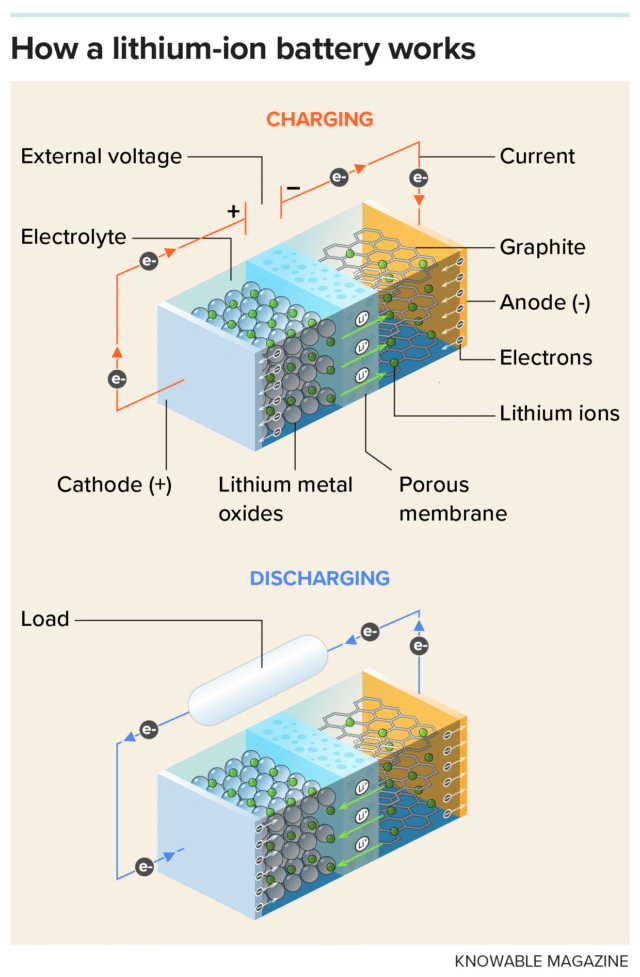

Charging a standard lithium-ion battery (top) works by applying a voltage between cathode and anode. This pulls lithium atoms from the cathode and strips off an electron from each. The now positively charged lithium ions then flow across the membrane to the negatively charged anode. There, the ions reunite with the electrons, which flowed through an external circuit as an electric current. These now neutral atoms nest in the graphite lattice until needed again. The battery’s discharge cycle (bottom) is just the reverse: Electrons deliver energy to your cell phone or electric car as they flow via a circuit from anode to cathode, while lithium ions race through the membrane to meet them there.

Credit: Knowable Magazine

Charging a standard lithium-ion battery (top) works by applying a voltage between cathode and anode. This pulls lithium atoms from the cathode and strips off an electron from each. The now positively charged lithium ions then flow across the membrane to the negatively charged anode. There, the ions reunite with the electrons, which flowed through an external circuit as an electric current. These now neutral atoms nest in the graphite lattice until needed again. The battery’s discharge cycle (bottom) is just the reverse: Electrons deliver energy to your cell phone or electric car as they flow via a circuit from anode to cathode, while lithium ions race through the membrane to meet them there. Credit: Knowable Magazine

They’ve also gotten really cheap, comparatively speaking. When Japan’s Sony Corporation introduced the first commercial lithium-ion battery in 1991, drawing on a worldwide research effort dating back to the 1950s, it powered one of the company’s camcorders and cost the equivalent of $7,500 for every kilowatt-hour (KwH) of energy it stored. By April 2025 lithium-ion battery prices had plummeted to $115 per KwH, and were projected to fall toward $80 per KwH or less by 2030—low enough to make a new EV substantially cheaper than the equivalent gasoline-powered vehicle.

“Most of these advancements haven’t really been down to any fundamental chemistry improvements,” says Mauro Pasta, an applied electrochemist at the University of Oxford. “What’s changed the game has been the economies of scale in manufacturing.”

Liu points to a prime example: the roll-to-roll process used for the cylindrical batteries found in most of today’s EVs. “You make a slurry,” says Liu, “then you cast the slurry into thin films, roll the films together with very high speed and precision, and you can make hundreds and thousands of cells very, very quickly with very high quality.”

Lithium-ion cells have also seen big advances in safety. The existence of that flammable electrolyte means that EV crashes can and do lead to hard-to-extinguish lithium-ion fires. But thanks to the circuit breakers and other safeguards built into modern battery packs, only about 25 EVs catch fire out of every 100,000 sold, versus some 1,500 fires per 100,000 conventional cars—which, of course, carry around large tanks of explosively flammable gasoline.

In fact, says McCalla, the standard lithium-ion industry is so far ahead that solid-state might never catch up. “EVs are going to scale today,” he says, “and they’re going with the technology that’s affordable today.” Indeed, battery manufacturers are ramping up their lithium-ion capacity as fast as they can. “So I wonder if the train has already left the station.”

But maybe not. Solid-state technology does have a geopolitical appeal, notes Ying Shirley Meng, a materials scientist at the University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory. “With lithium-ion batteries the game is over—China already dominates 70 percent of the manufacturing,” she says. So for any country looking to lead the next battery revolution, “solid-state presents a very exciting opportunity.”

Performance potential

Another plus is improved performance. At the very time that EV buyers are looking for ever greater range and charging speed, says Louli, the standard lithium-ion recipe is hitting a performance plateau. To do better, he says, “you have to go back and start doing some material innovations”—like those in solid-state batteries.

Take the standard battery’s liquid electrolyte, for example. It’s not only flammable, but also a limitation on charging speed. When you plug in an electric car, the charging cable acts as an external circuit that’s applying a voltage between the battery’s two electrodes, the cathode and the anode. The resulting electrical forces are strong enough to pull lithium atoms out of the cathode and to strip one electron from each atom. But when they drag the resulting ions through the electrolyte toward the anode, they hit the speed limit: Try to rush the ions along by upping the voltage too far and the electrolyte will chemically break down, ending the battery’s charging days forever.

So score one for solid-state batteries: Not only do the best superionic conductors offer a faster ion flow than liquid electrolytes, they also can tolerate higher voltages—all of which translates into EV recharges in under 10 minutes, versus half an hour or more for today’s lithium-ion power packs.

Score another win for solid-state when the ions arrive at the opposite electrode, the anode, during charging. This is where they reunite with their lost electrons, which have taken the long way around through the external circuit. And this is where standard lithium-ion batteries store the newly neutralized lithium atoms in a layer of graphite.

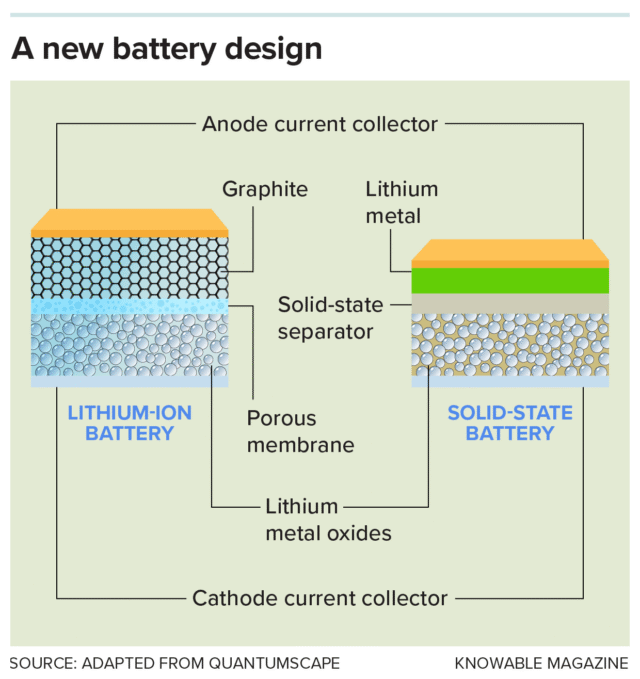

A solid-state battery doesn’t require a graphite cage to store lithium ions at the anode. This shrinks the overall size of the battery and increases its efficiency in uses such as an electric vehicle power pack. The solid-state design also replaces the porous membrane in the middle with a sturdier barrier. The aim is to create a battery that’s more light-weight, safer, stores more energy and makes recharging more convenient than current electric car batteries.

Credit: Knowable Magazine

A solid-state battery doesn’t require a graphite cage to store lithium ions at the anode. This shrinks the overall size of the battery and increases its efficiency in uses such as an electric vehicle power pack. The solid-state design also replaces the porous membrane in the middle with a sturdier barrier. The aim is to create a battery that’s more light-weight, safer, stores more energy and makes recharging more convenient than current electric car batteries. Credit: Knowable Magazine

Graphite anodes were a major commercial advance in 1991—the innovation that finally brought lithium-ion batteries out of the lab and into the marketplace. Graphite is cheap, chemically stable, excellent at conducting electricity, and able to slot those incoming lithium atoms into its hexagonal carbon lattice like so many eggs in an egg carton.

But graphite imposes yet another charging rate limit, since the lattice can handle only so many ions crowding in at once. And it’s heavy, wasting a lot of mass and volume on a simple container, says Louli: “Graphite is an accommodating host, but it does not deliver energy itself—it’s a passive component.” That’s why range-conscious automakers are eager for an alternative to graphite: The more capacity an EV can cram into the same-sized battery pack, and the less weight it has to haul around, the farther it can go on a single charge.

The ultimate alternative would be no cage at all, with no wasted space or weight—just incoming ions condensing into pure lithium metal with every charging cycle. In effect, such a metallic lithium anode would create and then dissolve itself with every charge and discharge cycle—while storing maybe 10 times more electrical energy per gram than a graphite anode.

Such lithium-metal anodes have been demonstrated in the lab since at least the 1970s, and even featured in some early, unsuccessful attempts at commercial lithium batteries. But even after decades of trying, says Louli, no one has been able to make metal anodes work safely and reliably in contact with liquid electrolytes. For one thing, he says, you get these reactions between your liquid electrolyte and the lithium metal that degrade them both, and you end up with a very bad battery lifetime.

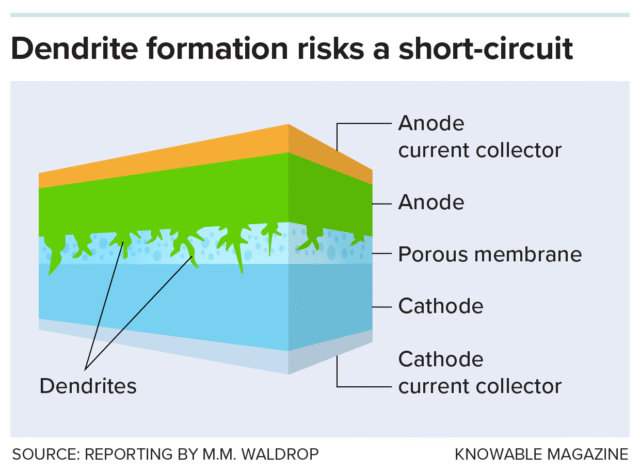

And for another, adds Wachsman, “when you are charging a battery with liquids, the lithium going to the anode can plate out non-uniformly and form what are called dendrites.” These jagged spikes of metal can grow in unpredictable ways and pierce the battery’s separator layer: a thin film of electrically insulating polymer that keeps the two electrodes from touching one another. Breaching that barrier could easily cause a short circuit that abruptly ends the device’s useful life, or even sets it on fire.

Standard lithium-ion batteries don’t use lithium-metal anodes because there is too high a risk of the metal forming sharp spikes called dendrites. Such dendrites can easily pierce the porous polymer membrane that separates anode from cathode, causing a short-circuit or even sparking a fire. Solid-state batteries replace the membrane with a solid barrier.

Credit: Knowable Magazine

Standard lithium-ion batteries don’t use lithium-metal anodes because there is too high a risk of the metal forming sharp spikes called dendrites. Such dendrites can easily pierce the porous polymer membrane that separates anode from cathode, causing a short-circuit or even sparking a fire. Solid-state batteries replace the membrane with a solid barrier. Credit: Knowable Magazine

Now compare this with a battery that replaces both the liquid electrolyte and the separator with a solid-state layer tough enough to resist those spikes, says Wachsman. “It has the potential of, one, being stable to higher voltages; two, being stable in the presence of lithium metal; and three, preventing those dendrites”—just about everything you need to make those ultra-high-energy-density lithium-metal anodes a practical reality.

“That is what is really attractive about this new battery technology,” says Louli. And now that researchers have found so many superionic solids that could potentially work, he adds, “this is what’s driving the push for it.”

Manufacturing challenges

Increasingly, in fact, the field’s focus has shifted from research to practice, figuring out how to work the same kind of large-scale, low-cost manufacturing magic that’s made the standard lithium-ion architecture so dominant. These new superionic materials haven’t made it easy.

A prime example is the class of sulfides discovered by Japanese researchers in 2011. Not only were these sulfides among the first of the new superionics to be discovered, says Wachsman, they are still the leading contenders for early commercialization.

Major investments have come from startups such as Colorado-based Solid Power and Massachusetts-based Factorial Energy, as well as established battery giants such as China’s CATL and global carmakers such as Toyota and Honda.

And there’s one big reason for the focus on superionic sulfides, says Wachsman: “They’re easy to drop into existing battery cell manufacturing lines,” including the roll-to-roll process. “Companies have got billions of dollars invested in the existing infrastructure, and they don’t want to just displace that with something new.”

Yet these superionic sulfides also have some significant downsides—most notably, their extreme sensitivity to humidity. This complicates the drop-in process, says Oxford’s Pasta. The dry rooms that are currently used to manufacture lithium-ion batteries have a humidity content that is not nearly low enough for sulfide electrolytes, and would have to be retooled. That sensitivity also poses a safety risk if the batteries are ever ruptured in an accident, he says: “If you expose the sulfides to humidity in the air you will generate hydrogen sulfide gas, which is extremely toxic.”

All of which is why startups such as QuantumScape, and the Maryland-based Ion Storage Systems that spun out of Wachsman’s lab in 2015, are looking beyond sulfides to solid-state oxide electrolytes. These materials are essentially ceramics, says Wachsman, made in a high-tech version of pottery class: “You shape the clay, you fire it in a kiln, and it’s a solid.” Except that in this case, it’s a superionic solid that’s all but impervious to humidity, heat, fire, high voltage, and highly reactive lithium metal.

Yet that’s also where the manufacturing challenges start. Superionic or not, for example, ceramics are too brittle for roll-to-roll processing. Once they have been fired and solidified, says Wachsman, “you have to handle them more like a semiconductor wafer, with machines to cut the sheets to size and robotics to move them around.”

Then there’s the “reversible breathing” that plagues oxide and sulfide batteries alike: “With every charging cycle we’re plating and stripping lithium metal at the anode,” explains Louli. “So your entire cell stack will have a thickness increase when you charge and a thickness decrease when you discharge”—a cycle of tiny changes in volume that every solid-state battery design has to allow for.

At QuantumScape, for example, individual battery cells are made by stacking a number of gossamer-thin oxide sheets like a deck of cards, then encasing this stack inside a metal frame that is just thick enough to let the anode layer on each sheet freely expand and contract. The stack and the frame together are then vacuum-sealed into a soft-sided pouch, says Louli, “so if you pack the cells frame to frame, the stacks can breathe and not push on the adjacent cells.”

In a similar way, says Wachsman, all the complications of solid-state batteries have ready solutions—but solutions that inevitably add complexity and cost. Thus the field’s increasingly urgent obsession with manufacturing. Before an auto company will even consider adopting a new EV battery, he says, “it not only has to be better-performing than their current battery, it has to be cheaper.”

And the only way to make complicated technology cheaper is with economies of scale. “That’s why the biggest impediment to solid-state batteries is just the cost of standing up one of these gigafactories to make them in sufficient volume,” says Wachsman. “That’s why there’s probably going to be more solid-state batteries in early adopter-type applications that don’t require that kind of volume.”

Still, says Louli, the long-term demand is definitely there. “What we’re trying to enable by combining the lithium-metal anode with solid-state technology is threefold,” he says: “Higher energy, higher power and improved safety. So for high-performance applications like electric vehicles—or other applications that require high power density, such as drones or even electrified aviation—solid-state batteries are going to be well-suited.”

This story originally appeared in Knowable Magazine.

How close are we to solid state batteries for electric vehicles? Read More »