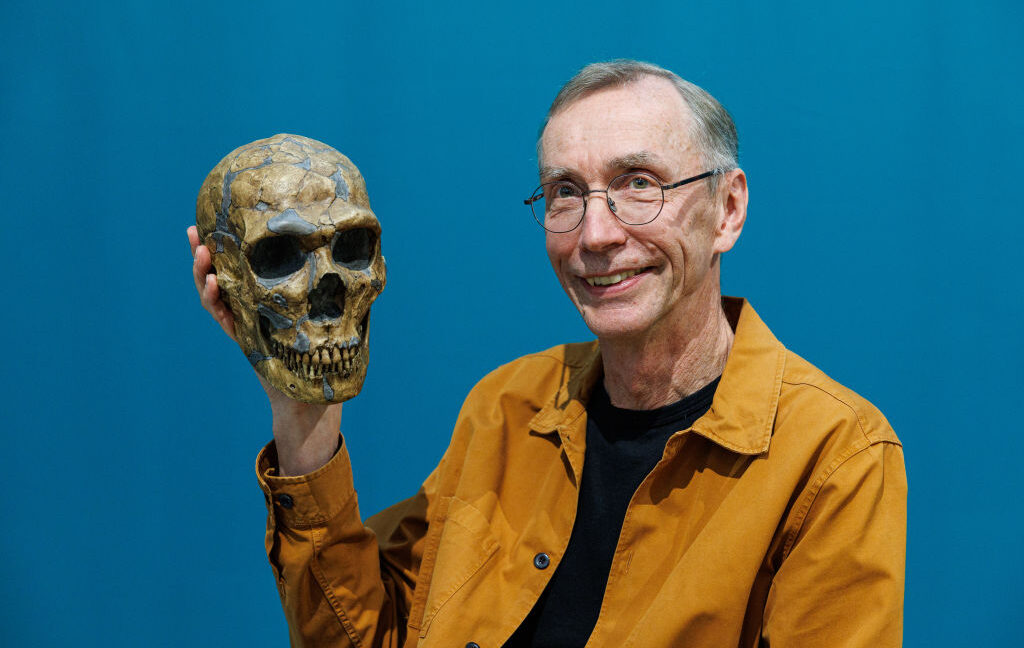

Neanderthals seemed to have a thing for modern human women

By now, it’s firmly established that modern humans and their Neanderthal relatives met and mated as our ancestors expanded out of Africa, resulting in a substantial amount of Neanderthal DNA scattered throughout our genome. Less widely recognized is that some of the Neanderthal genomes we’ve seen have pieces of modern human DNA as well.

Not every modern human has the same set of Neanderthal DNA, however; different people will, by chance, have inherited different fragments. But there are also some areas, termed “Neanderthal deserts,” where none of the Neanderthal DNA seems to have persisted. Notably, the largest Neanderthal desert is the entire X chromosome, raising questions about whether this reflects the evolutionary fitness of genes there or mating preferences.

Now, three researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Alexander Platt, Daniel N. Harris, and Sarah Tishkoff, have done the converse analysis: examining the X chromosomes of the handful of completed genomes we have. It turns out there’s also a strong bias toward modern human sequences there, as well, and the authors interpret that as selective mating, with Neanderthal males showing a strong preference for modern human females and their descendants.

What type of selection are we looking at?

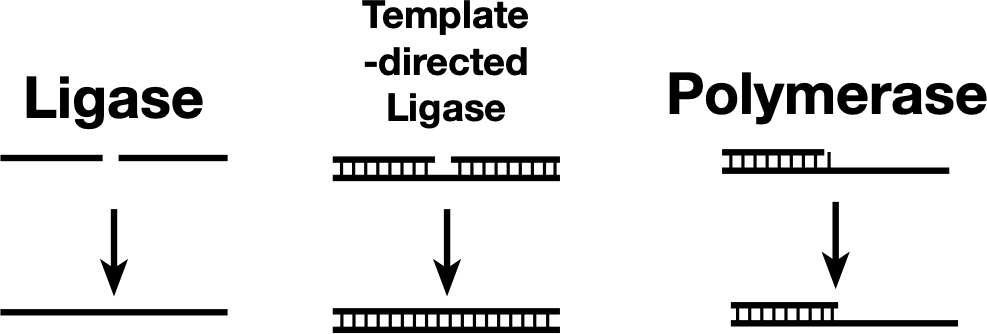

Given how long modern humans and Neanderthals had been evolving as separate populations, some degree of genetic incompatibility is definitely possible. Lots of proteins interact in various ways, and the genes behind these interaction networks will evolve together—a change in one gene will often lead to compensatory changes in other genes in the network. Over time, those changes may mean re-introducing the original gene will actually disrupt the network, with a negative impact on fitness.

That means the introduction of some Neanderthal genes into the modern human genome (or vice versa) would be disruptive and make carriers of them less fit. So they’d be selected against and lost over the ensuing generations. Of course, some segments would likely be lost at random—the genome’s pretty big, and the modern human population was likely large and growing, allowing its DNA to dilute out the influence of other human populations. Figuring out which influence is dominant can be challenging.

Neanderthals seemed to have a thing for modern human women Read More »