Economics Roundup #6

I obviously cover many economical things in the ordinary course of business, but I try to reserve the sufficiently out of place or in the weeds stuff that is not time sensitive for updates like this one.

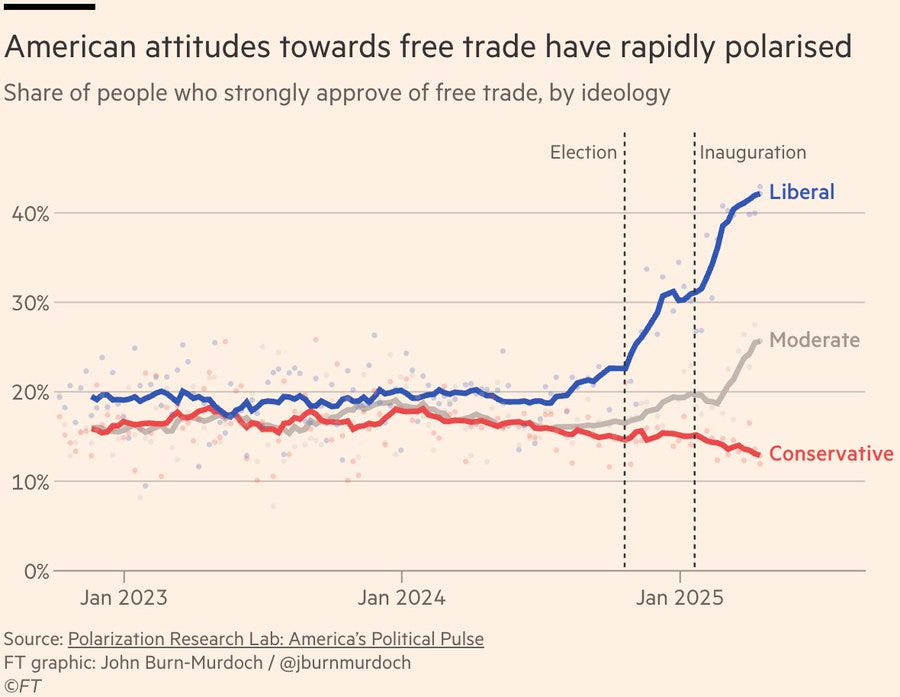

We love trade now, so maybe it’ll all turn out great?

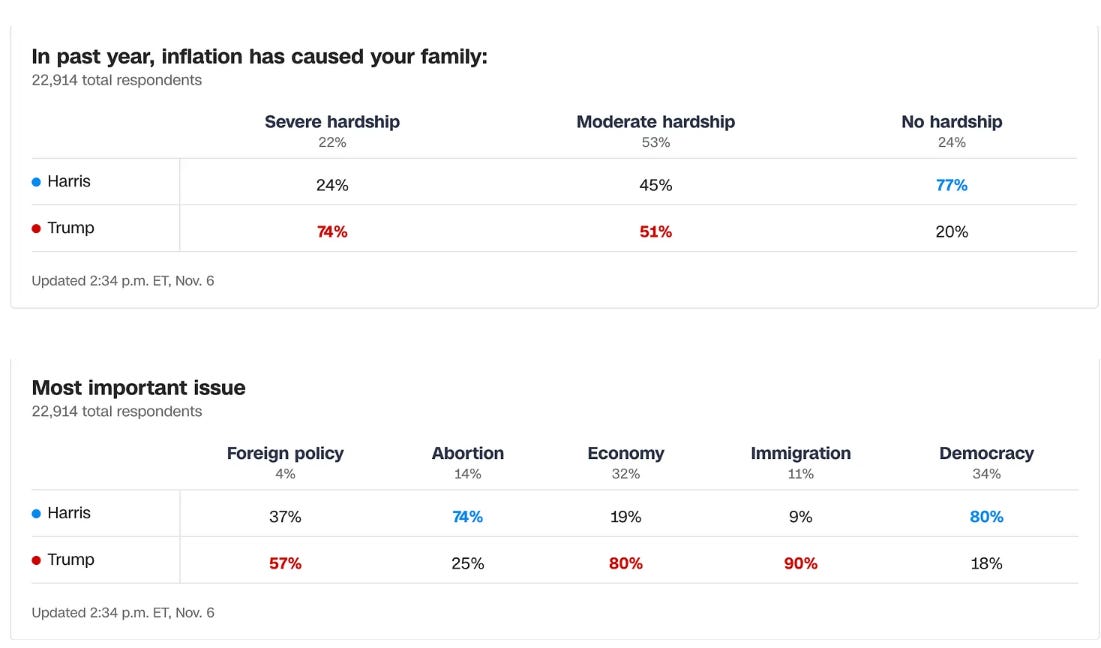

John Burn-Murdoch: Negative partisanship is a helluva drug:

Up until a few months ago, liberal and conservative Americans held pretty much the same views on free trade.

Now, not so much…

Yet another explanation that says ‘the China shock killed particular jobs but had large diffuse benefits and left us all much better off.’

Alex Recouso: The recent capital gains tax increase in the UK was expected to bring additional tax revenue.

Instead, high-net-worth individuals and families are leaving the country leading to an 18% fall in net capital gains tax revenue. A £2.7b loss.

Welcome to the Laffer curve, suckers.

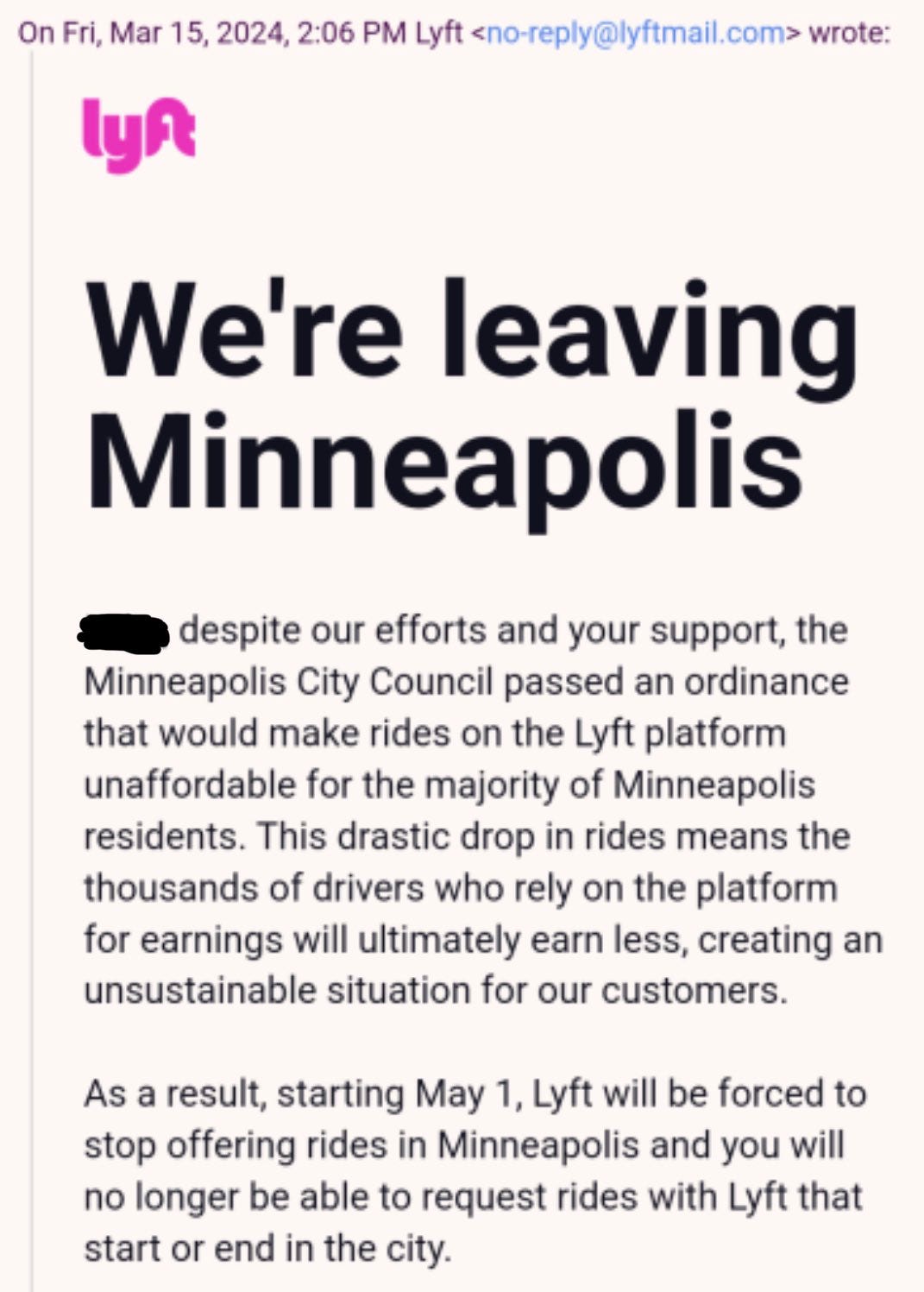

Here’s what looks at first like a wild paper, claiming that surge pricing is great overall and fantastic for riders increasing their surplus by 3.57%, but that it decreases driver surplus by 0.98% and the platform’s current profits by 0.5% of gross revenue.

At first that made no sense, obviously raising prices will be good for drivers, and Uber wouldn’t do it if it lowered revenue.

This result only makes sense once you realize that the paper is not holding non-surge pricing constant. It assumes without surge pricing, Uber would raise their baseline rates substantially. That’s also why this is bad for workers with long hours at off-peak times, as their revenue declines. Uber could raise more revenue now with higher off-peak hours, but it prefers to focus on the long term, which helps riders and hurts drivers.

That makes sense, but it also raises the question of why Uber is keeping prices so low at this point. Early on, sure, you’re growing the market and fighting for market share. But now, the market is mature, and has settled into a duopoly. Is Uber that afraid of competition? Is it simply corporate culture and inertia? I mean, Uber, never change (in this particular way), but it doesn’t seem optimal from your perspective.

Story mostly checks out in theory, as the practice is commonly used, with some notes. If tips are 90%+ a function of how much you tip in general, and vary almost none based on service, at equilibrium they’re mostly a tax on tippers paid to non-tippers.

Gabriel: it’s actually hilarious how tipping is just redistribution of capital from people pleasers to non people pleasers

tipping never increases salaries in the long run because free markets, so our entire tip becomes savings of the rude people that don’t tip ironically.

say waiters started earning 30% more from tips, then everyone wants to become a waiter, and now businesses can decrease salaries to match market value. more restaurants will be started from tipping, not an increase in salary

tipping would have served a great purpose if it was socially acceptable to not tip, cause people doing a great job and who are nice would be paid more than the not nice people

i always tip cause i feel bad if i wouldn’t, but in theory your tip makes no difference and markets would adjust accordingly in the long run (but slightly inefficiently since you’d be spending less until menu prices actually increase)

Nitish Panesar: It’s wild how “voluntary” generosity just ends up subsidizing the less generous Makes you wonder if the system is rewarding the exact opposite of what we hope.

It’s not only a distribution from pleasers to non-pleasers, it is also from truth tellers to liars, because being able to say that you tip, and tip generously, is a lot of what people are really buying via their tips.

There are some additional effects.

-

The menu price illusion effect raises willingness to pay, people are silly.

-

Tax policy (e.g. ‘no tax on tips’ or not enforcing one) can be impacted.

-

Tips can create an effective floor on server pay if a place has some mix of high prices and general good tippers, assuming the tips don’t get confiscated. That floor could easily bind.

-

If you tip generously as a regular, some places do give you better service in various ways that can be worthwhile. And if you tip zero or very low systematically enough that people remember this, there will be a response in the other direction.

-

Note that the network of at least the Resy-level high end restaurants keep and share notes on their customers. So if you tip well or poorly at that level, word will likely get out, even if you go to different places.

It is also likely that you can effectively do acausal trade a la Parfit’s Hitchhiker (Parfit’s Diner?) as I bet waiters are mostly pretty good at figuring out who is and is not going to tip well.

The other factor is, even if tipping as currently implemented doesn’t work in theory, it seems suspiciously like it works in practice – in the sense that American service in restaurants in particular is in general vastly better than in other places. It’s not obvious whether that would have been true anyway, but if it works, even if it in theory shouldn’t? Then it is totally worth all the weird effects.

The tax benefits of rewarding people via orgies, as a form of non-wage compensation. That is on top of the other benefits, as certain things cannot be purchased, purchased on behalf of others or even asked for without degrading their value. The perfect gift!

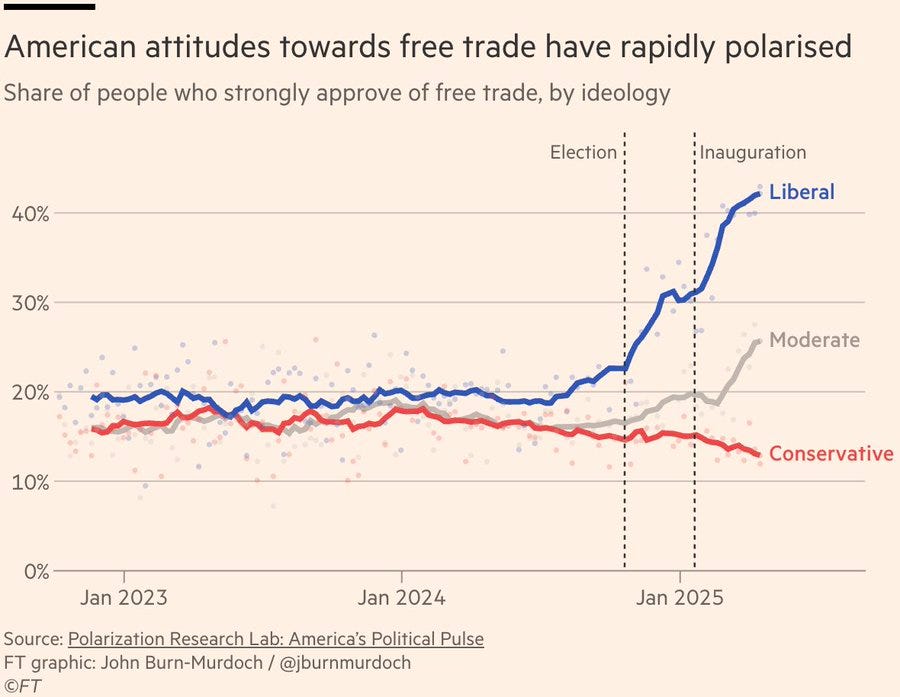

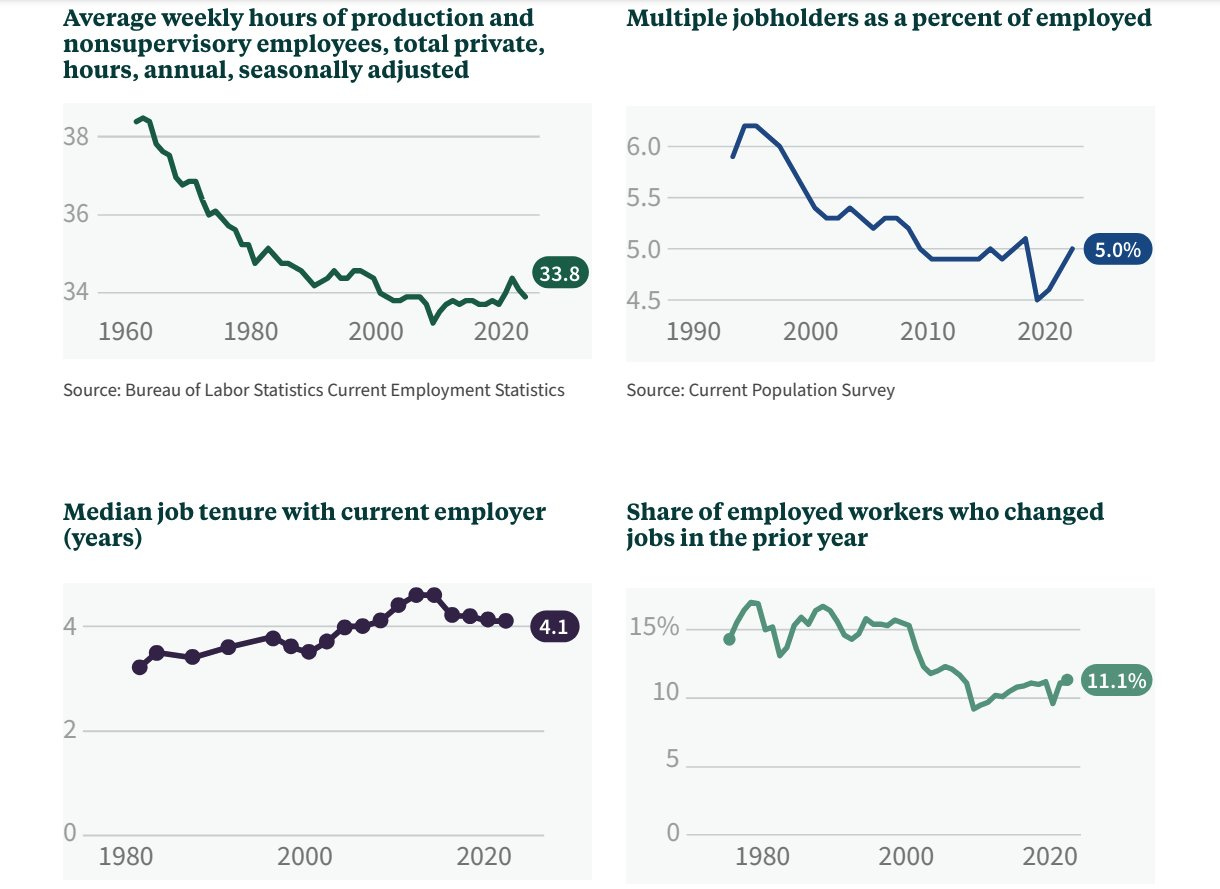

Even though we are taking longer retirements, the sheer amount of work being done is staying roughly flat over time:

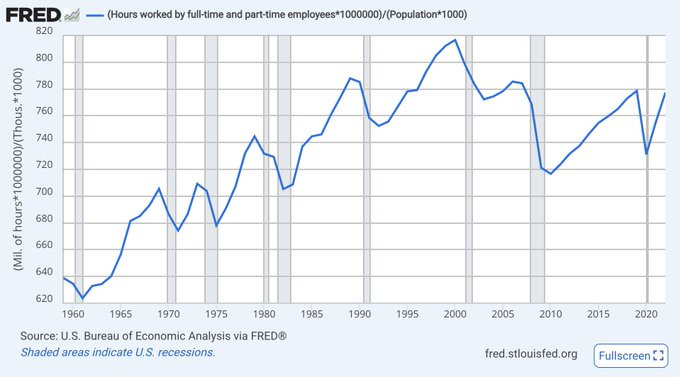

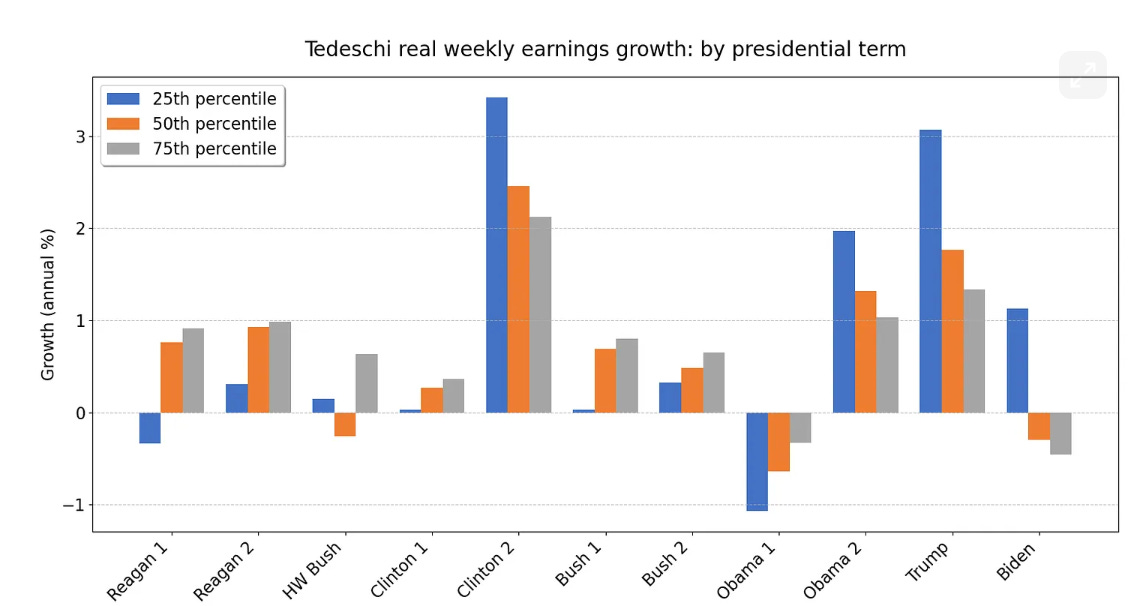

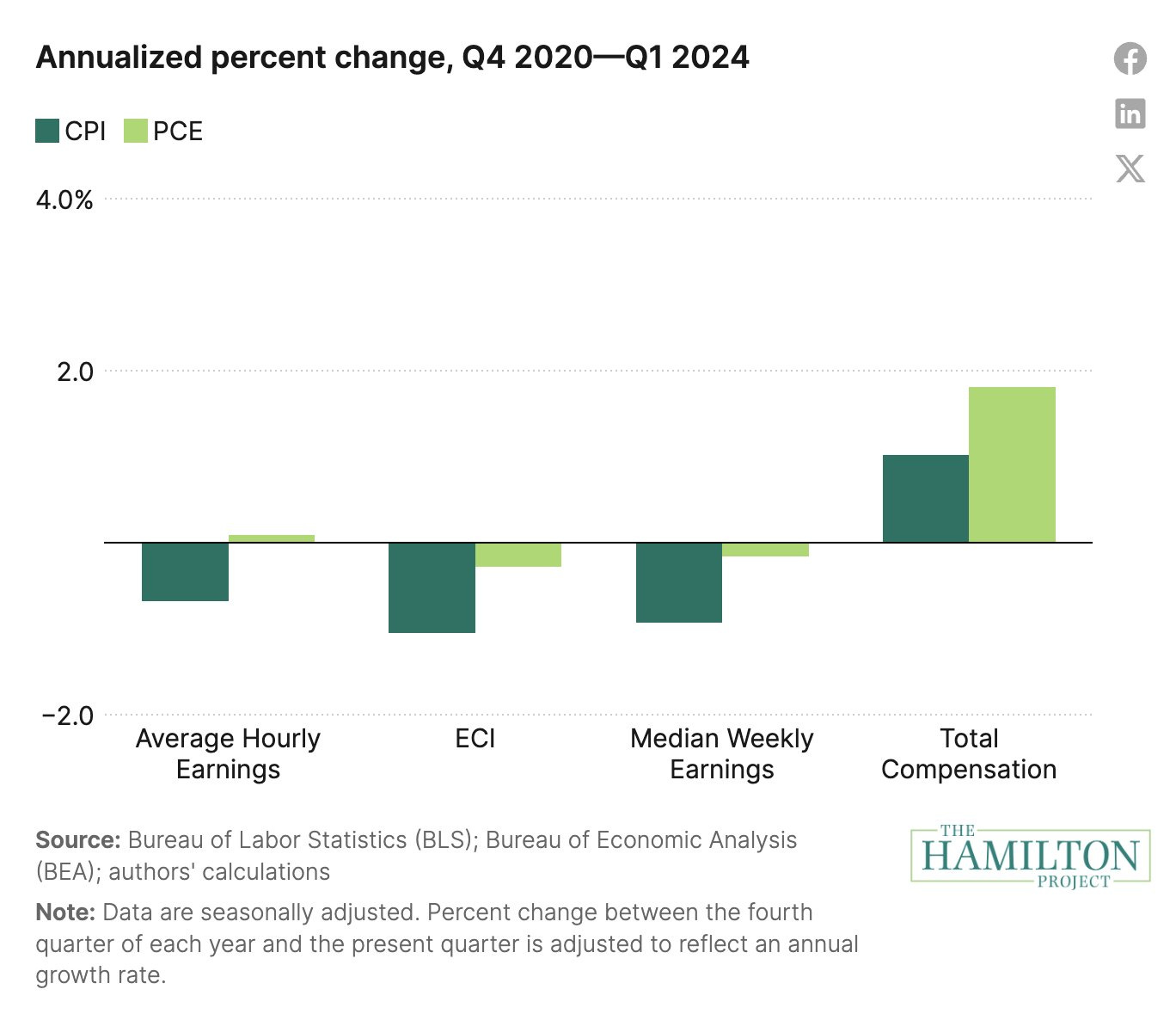

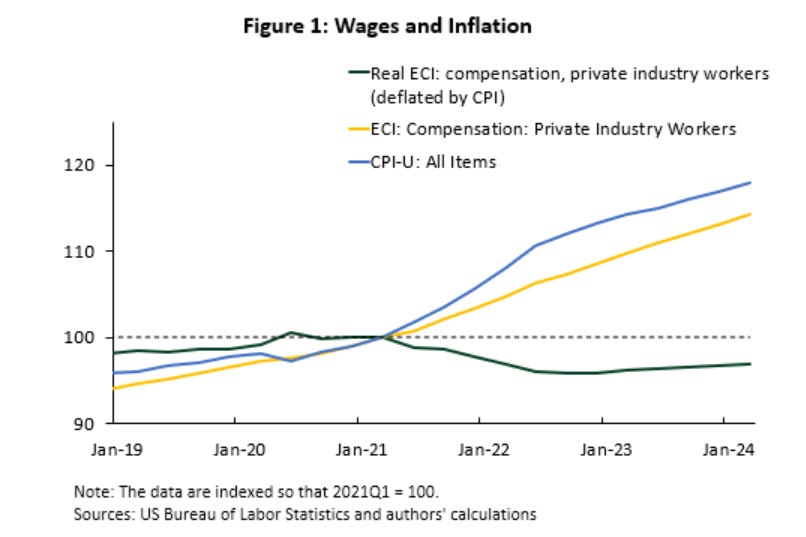

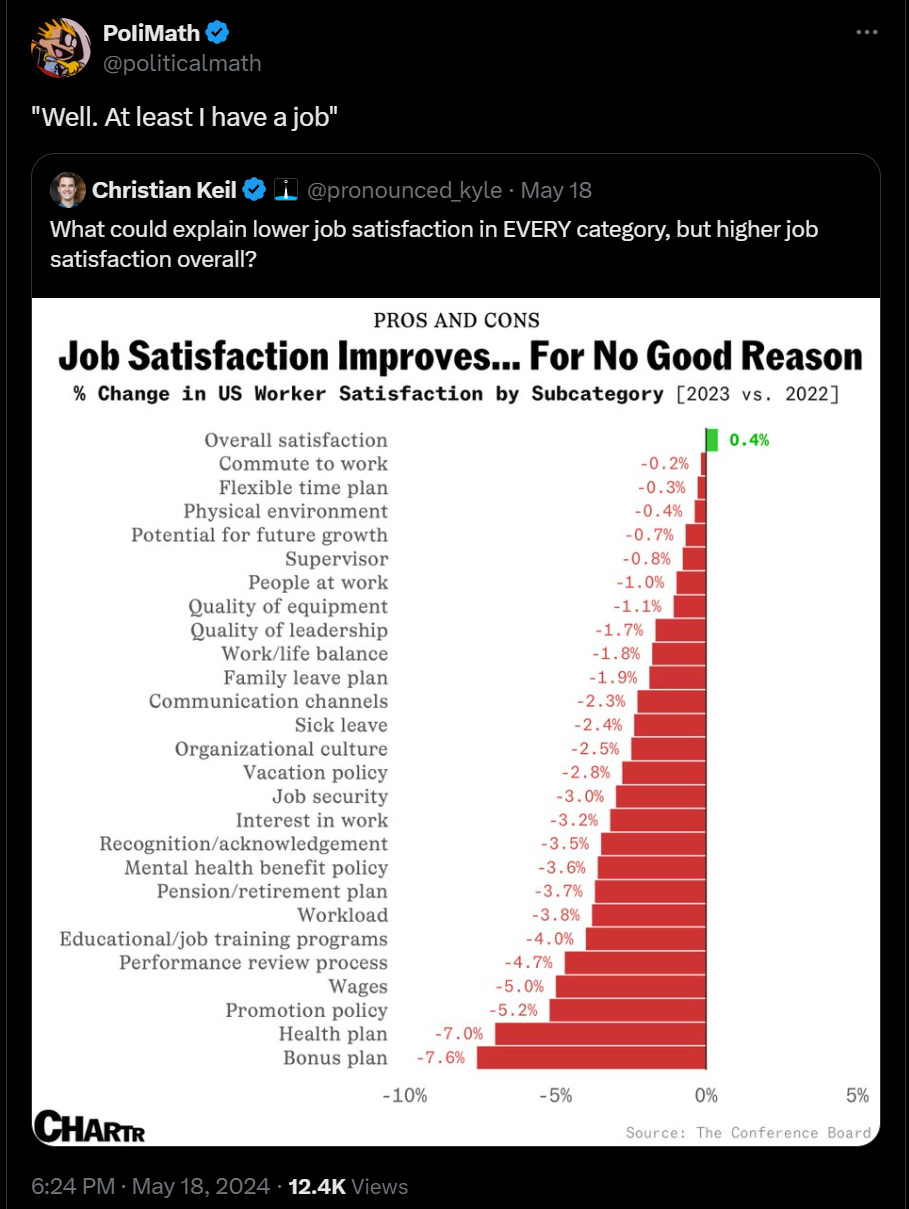

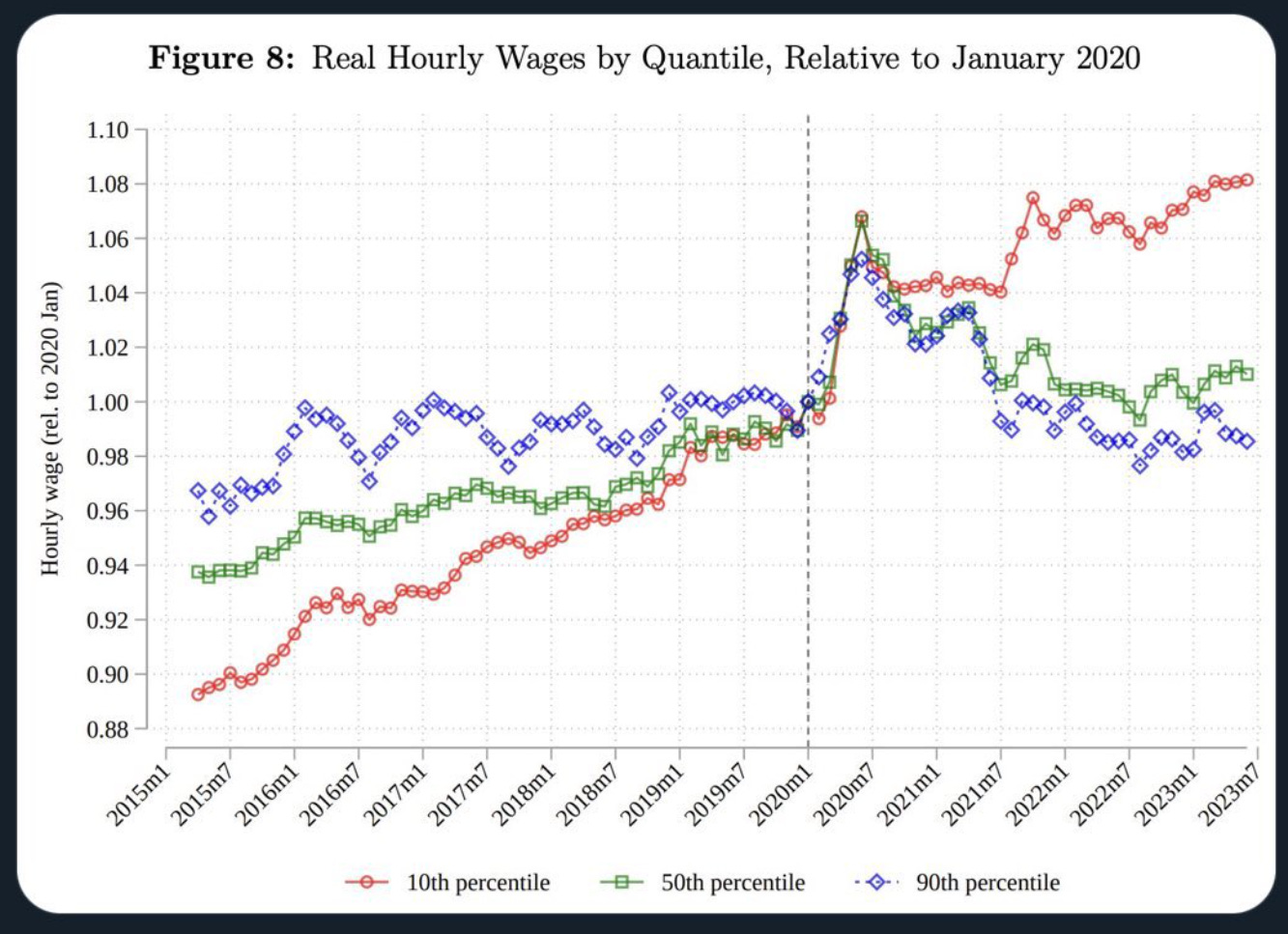

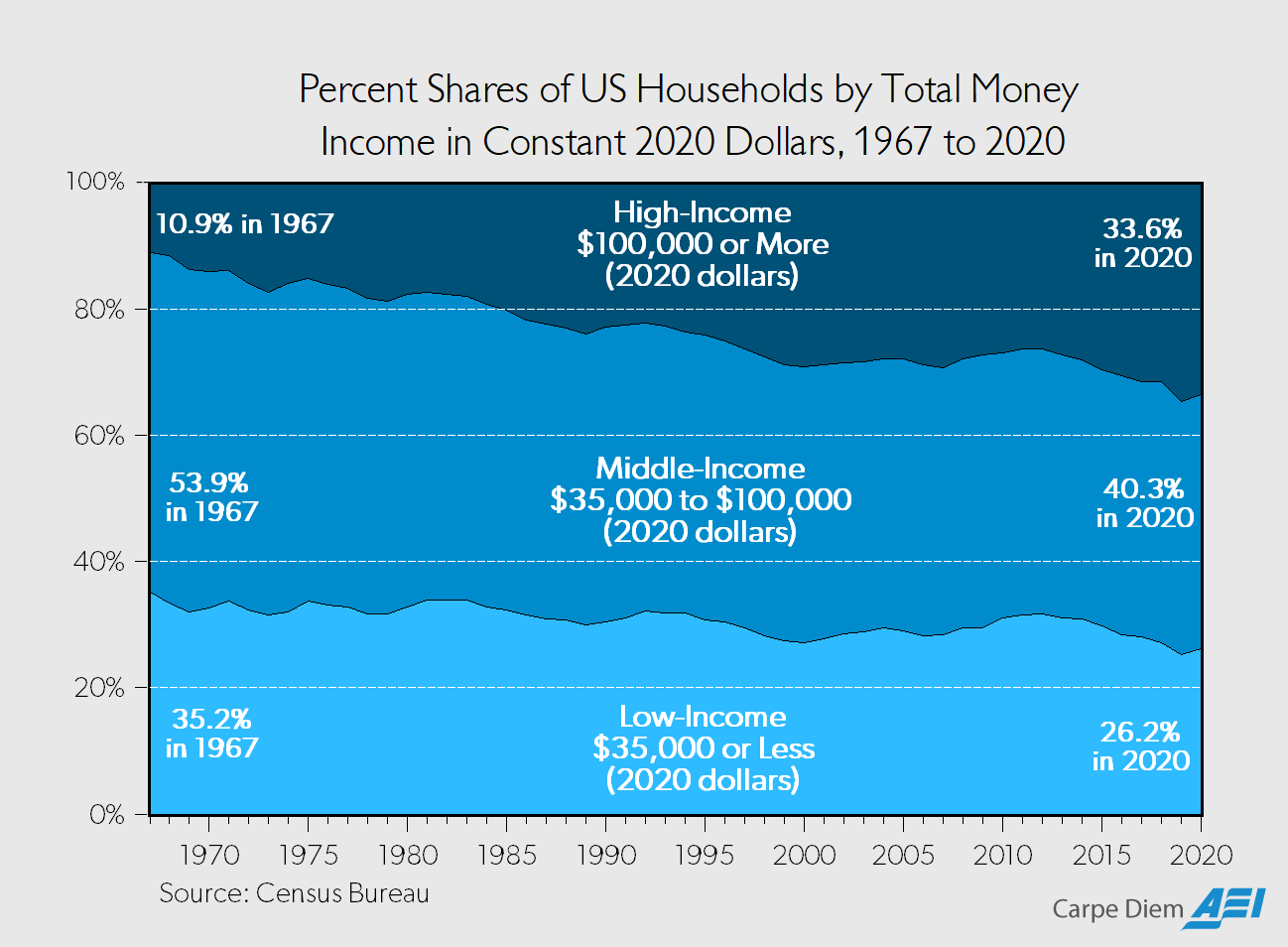

Noah Smith explains that the divergence between mean productivity and median wages is mostly about unequal compensation, and when you adjust the classic divergence chart in several ways, the gap between wages and productivity declines dramatically, although not entirely:

That also says that real median wages are up 16.3% over that period. One can also consider that this is all part of the story of being forced to purchase more and better goods and services, without getting the additional funds to do that. As I’ve said, I do think that life as the median worker did get net harder over that period, but things are a lot less crazy than people think.

Matt Bruenig attempts a definitive response to the controversy around ‘how many Americans live paycheck to paycheck?’ Man, it’s weird.

For starters, what the hell does that actually mean? When advocates cite it, they clearly mean that such people are ‘one expense away from disaster’ but the studies they cite mostly mean something else, which is a low savings rate.

It seems all the major surveys people cite are actually asking about low savings rate.

The go-to LendingClub claim that it’s 60% of Americans asks if someone’s savings rate is zero or less. We also have BankRate at 34%, asking essentially the same question, that’s a huge gap. Bank of America got 50% to either agree or strongly agree.

Bank of America also looked at people’s expenses in detail to see who used 95% or more of household income on ‘necessity spending’ and got 26% but that whole process seems super weird and wonky, I wouldn’t rely on it for anything.

Whereas the median American net worth is $192,700 with a liquid net worth of $7,850. Which after adjustments is arguably only a month of income. But 54% of Americans, when asked in a survey, said they had 3 months of savings available. But then 24% of people who said that then said they ‘couldn’t afford’ an emergency expense of $2k, what? So it’s weird. $8k is still very different from the ‘most Americans can’t pay a few thousand in expenses’ claims we often see, and this is before you start using credit cards or other forms of credit.

So, yeah, it’s all very weird. People aren’t answering in ways that are logically consistent or that make much sense.

What is clear is that when people cite how many Americans are ‘living paycheck to paycheck,’ almost always they are presenting a highly false impression. The map you would take away from that claim does not match the territory.

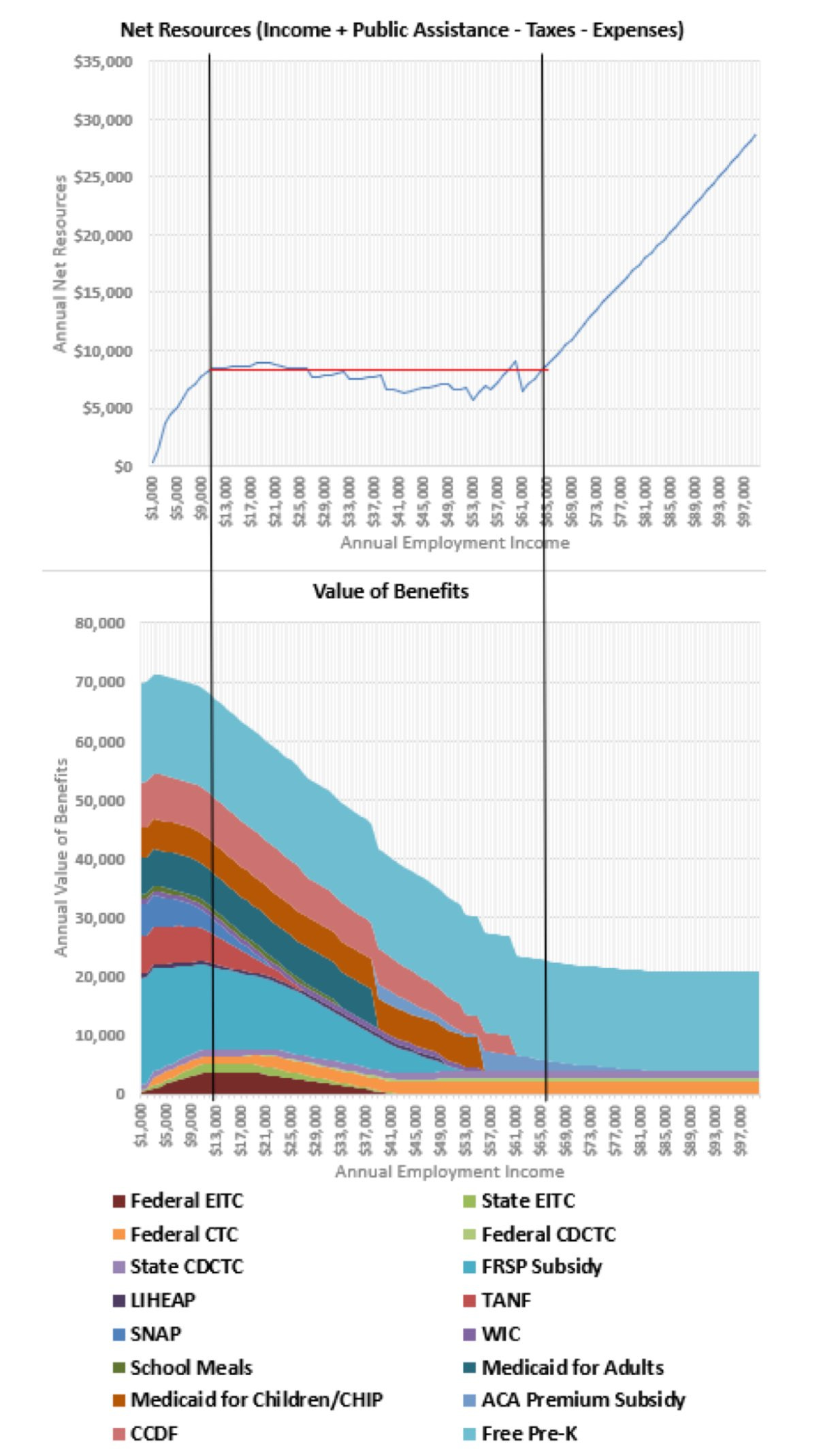

In addition to the ‘half of Americans live paycheck to paycheck’ claims being well-known to be objectively false, there’s another mystery behind them that Matt Yglesias points out. What policies would prevent this from being true? The more of a social safety net you provide, the less costly it is to live ‘paycheck to paycheck’ and the more people will do it. If you want people to have savings that aren’t in effect provided by their safety nets, then take away their safety net, watch what happens.

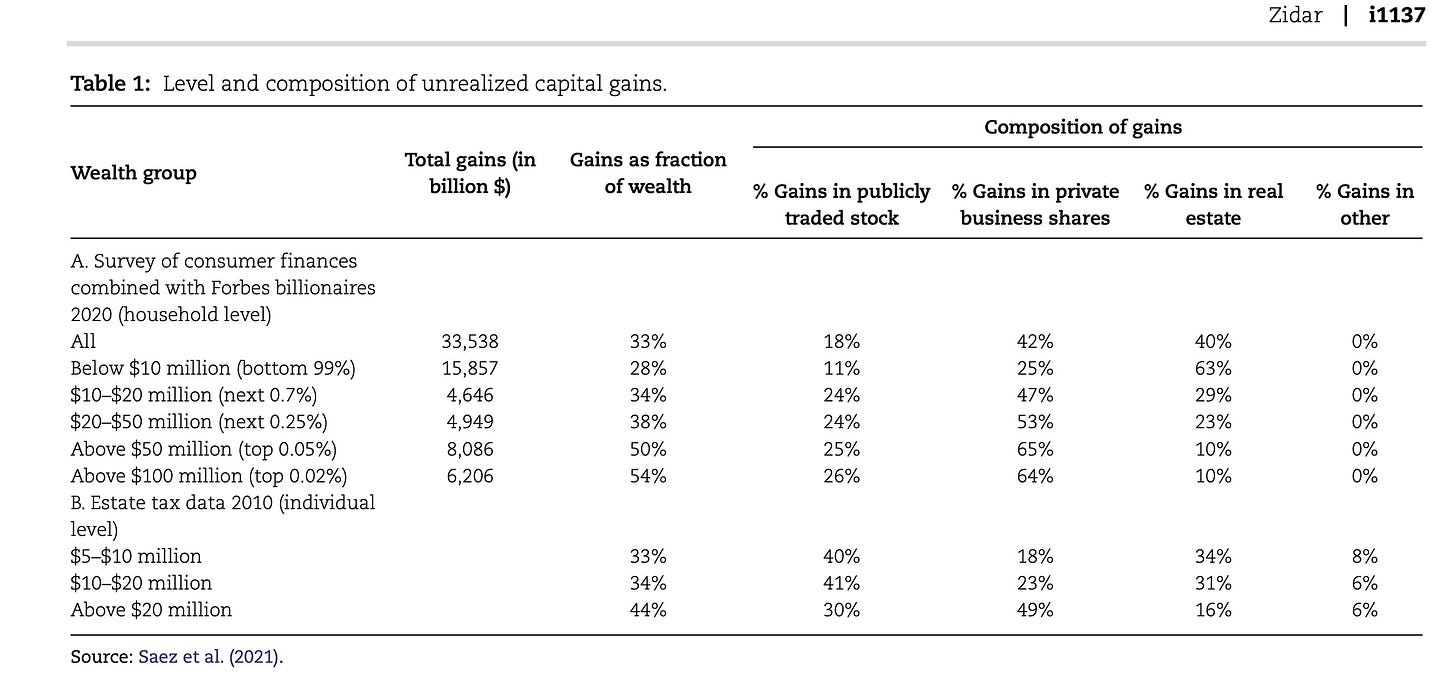

Unrealized capital gains create strange incentives. How much do the rich practice ‘buy, borrow, die’? The answer is some, but not all that much, with such borrowing being on average only 1-2% of economic income. Mostly they ‘buy, save, die,’ as their liquid incomes usually exceed consumption. The loophole should still be closed, especially as other changes could cause it to matter far more, but what matters is the cost basis step-up on death. There should at minimum be a cap on that.

Capitalists wisely have a norm that you are very not allowed to lie about revenue, to a far greater extent than you are not allowed to lie about other things. Revenue is a sacred trust. If you are counting secondary effects you absolutely cannot say the amount is ‘in revenue.’

Patrick McKenzie goes insanely deep on the seemingly unbelievable story about a woman withdrawing $50k in cash at the bank with very little questioning, and then losing it to a scammer. After an absurd amount of investigation, including tracking down The Room Where It Happened, it turned out the story all made sense. The bank let her withdraw the money because, if you take into account the equity in her house, she was actually wealthy, and the bank knew that so $50k did not raise so many alarm bells.

Patrick McKenzie pushes back against the idea that interchange fees and credit card rewards, taken together, are regressive redistribution. I find his argument convincing.

RIP to the US Bank Smartly Card that offered unlimited 4% cash back. They have no idea how there could have been such a big adverse selection problem.

Refund bonuses on crowdsourced projects give good incentives and signals all around, so they are highly effective at attracting more funding for privately created public goods. The problem is that if you do fail to fund or fail to deliver, and need to give out the bonus, that is a rather big disaster. So you win big on one level, and lose big on another. If I’m actively poorer when I fail, I’m going to have a high threshold for starting. Good selection, but you lose a lot of projects, some of which you want.

Federal Reserve Board removes ‘reputational risk’ component from bank exams, replacing them with more specific discussions of financial risk. This is plausibly a good change but there is a core function here we want to be preserving.

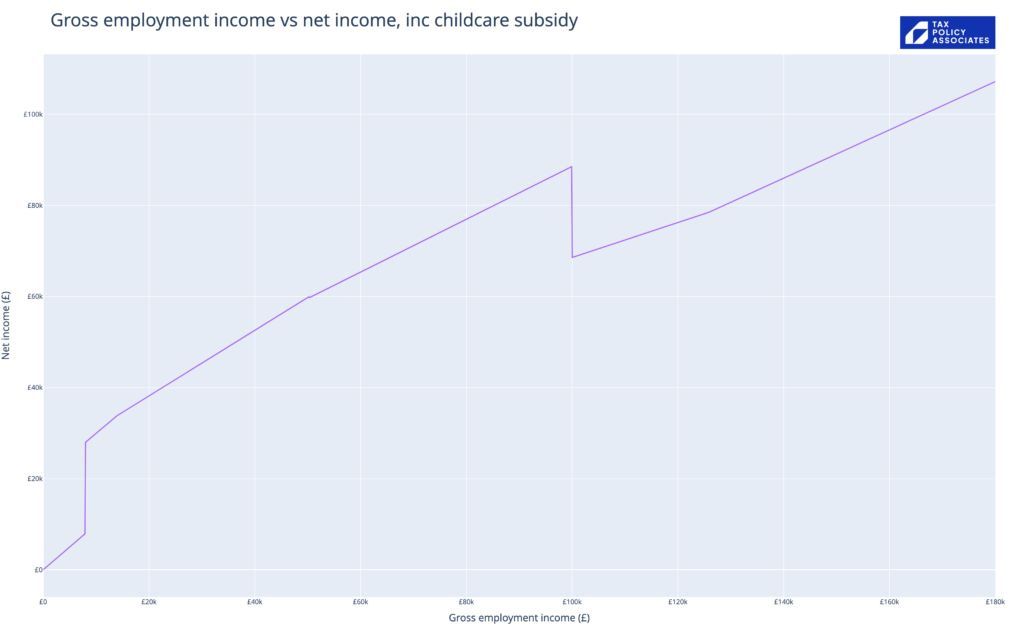

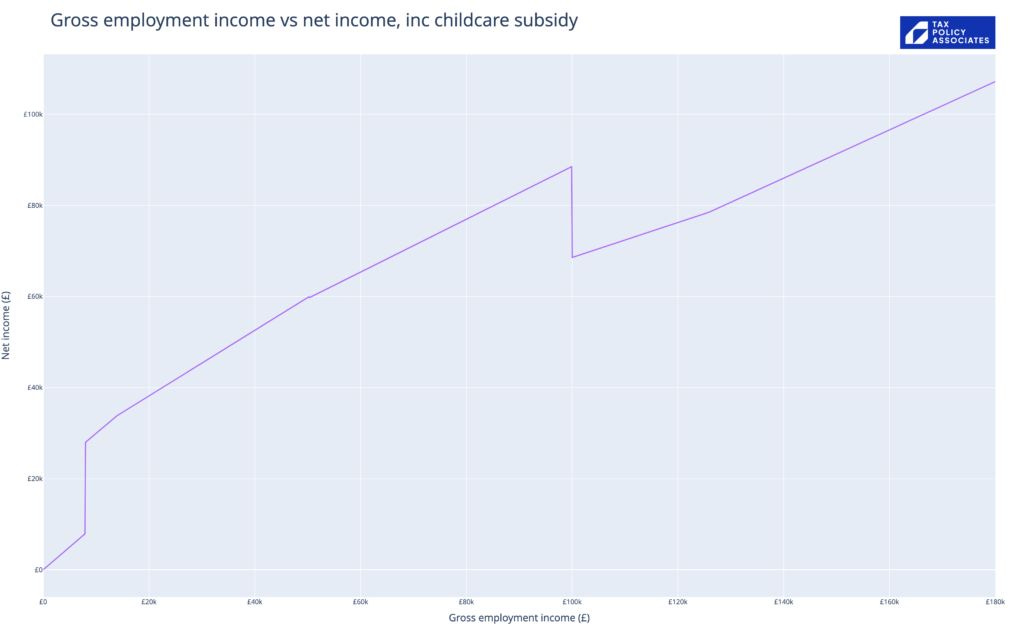

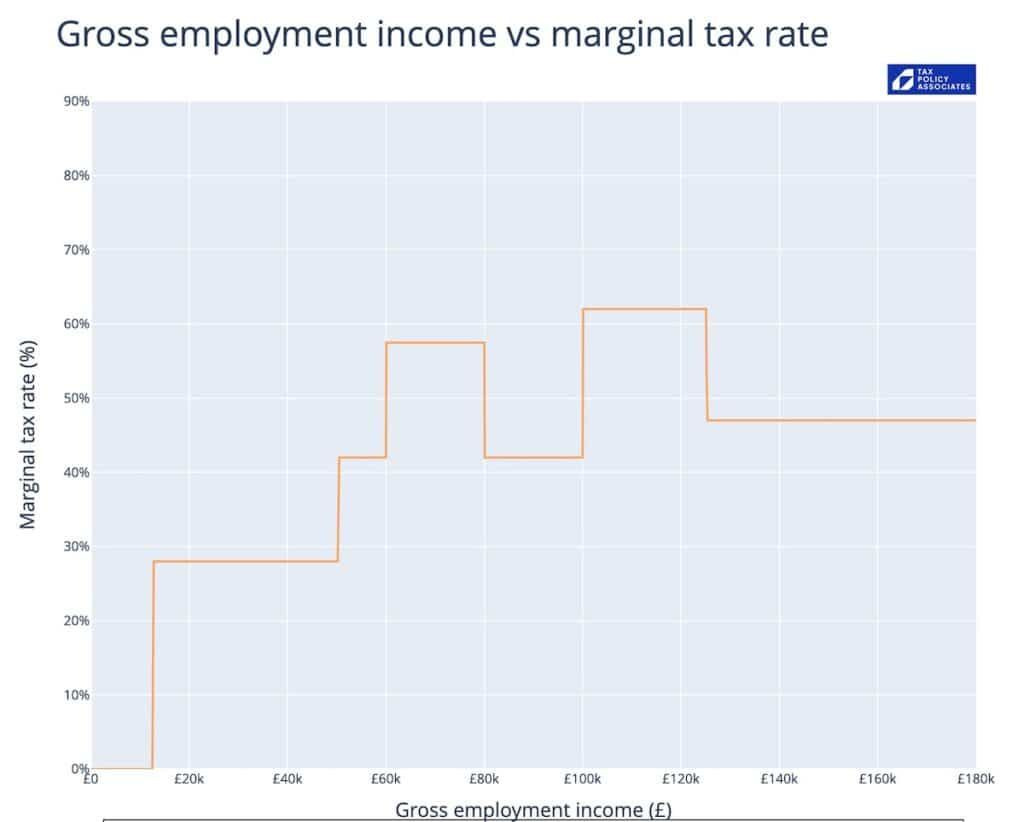

When you hire a real estate agent to help you buy a house, your agent’s direct financial incentive is to make you pay a higher price, not a lower one.

Darth Powell: LMFAO.

Austen Allred: I just realized the buyer’s agent in a real estate transaction has no incentive to help their customers get a better price

“But the agent isn’t going to rip you off, if you save $50k they only lose $1500.”

They’re just not going to scratch and claw to save every penny the same way I would if it were my money. Example: Very easy to say, “It’s competitive you should just put an offer in at asking.”

“But they want referrals.” Sure, but they have all of the information about what is reasonable and not.

“But they have a code of ethics.” Lol. Lmfao.

Given the math it’s very obvious that it’s a volume game. A real estate agent gets paid not by saving or making money, but by pushing deals through. It’s very clear incentive misalignment.

How does a buyer know if a deal is competitive, or if they need to move quickly? If the buying agent tells them it is. How does the buying agent know if a deal is competitive? If the selling agent tells them so. I’m sure that’s never been abused ever.

Steven Sinofsky: Anyone who has ever bought or sold a house comes to realize you’re mostly negotiating with your own agent, while your agent is mostly colluding with the other agent against both buyer and seller offering back incomplete information—an entirely unaligned transaction experience.

Sam Pullara: it is extremely difficult to align agents

Austen Allred: OpenAI has a team for that.

Astrus Dastan: And they’re failing miserably.

Yep, if you get 3% of the sale price you’re not going to fight for the lowest (or even highest, for the seller, if it means risking or dragging out the sale) possible price on that basis. It’s a volume business. But also it’s a reputation and networking business.

What this is missing is that I got my real estate agent because my best friend referred her to me, and then she actively warned us off of buying a few places until we found the right one and walked me through all the steps, and then because she did a great job fighting for me I recommended her to other clients and she got two additional commissions. The incentives are there.

As for the quoted transaction, well, yes, they were forced to leave money on the table because their agent negotiated with a dishonest and risky strategy, got their bluff called and it backfired. Tough. I’m guessing there won’t be a recommendation there.

People also think businesses try to follow the Ferengi Rules of Acquisition, basically?

Rashida Tlaib: Families are struggling to put food on the table. I sent a letter to @Kroger about their decision to roll out surge pricing using facial recognition technology. Facial recognition technology is often discriminatory and shouldn’t be used in grocery stores to price gouge residents.

Leon: >walk into kroger with diarrhea

>try to make my face seem normal

>grab $5 diarrhea medicine

>sharp pain hits my gut

>diarrhea medicine now costs $100

Something tells me that if they do that, then next time, if you have any choice whatsoever (and usually you do have such a choice) you’re not going to Kroger, and that’s the best case scenario for your reaction here. That’s the whole point of competition and capitalism.

What would actually happen if Kroger had the ability to do perfect price discrimination based on facial recognition? Basic economics says there would be higher volumes and less deadweight loss. Assuming there was competition from other stores such that profits stayed roughly the same, consumers would massively benefit.

The actual danger is the ‘try to make my face seem normal’ step. If you can plausibly spend resources to fool the system, then that spends everyone’s time and effort on games that do not produce anything. That’s the part to avoid. We’ve been doing this for a long time, with coupons and sales and other gimmicks that do price discrimination largely on the basis of willingness to do extra work. If anything basing on facial recognition seems better at that, and dynamic pricing should be better at managing inventory as well.

According to Victor Shih, China essentially says, no profits for you. The state won’t look kindly upon you if you try to turn too much of a profit.

Dwarkesh Patel: I asked Victor Shih this question – why has the Chinese stock market been flat for so long despite the economy growing so fast?

This puzzle is explained via China’s system of financial repression.

If you save money in China, banks are not giving you the true competitive interest rate. Rather, they’ll give you the government capped 1.3% (lower than inflation, meaning you’re earning a negative return).

The net interest (which is basically a tax on all Chinese savers) is shoveled into politically favored state owned enterprises that survive only on subsidized credit.

But here’s what I didn’t understand at first: Why don’t companies just raise equity capital and operate profitably for shareholders?

The answer apparently is that there’s no ‘outside’ the system.

The state doesn’t just control credit – it controls land, permits, market access, even board seats through Party committees. Companies that prioritize profits over market share lose these privileges. Those that play along get subsidized loans, regulatory favors, and government contracts.

Regular savers, founders, and investors are all turned into unwitting servants of China’s industrial policy.

The obvious follow-up question is why is there not epic capital flight by every dollar that isn’t under capital controls? Who would ever invest in a Chinese company if they had a choice (other than me, a fool whose portfolio includes IEMG)? Certainly not anyone outside China, and those inside China would only do it if they couldn’t buy outside assets, even treasuries or outside savings accounts. No reason to stick around while they drink your milkshake.

This falls under the category of ‘things that if America contemplated doing even 10% of what China does, various people would say this will instantly cause us to ‘Lose to China’’. I very much have zero desire to do this one, but perhaps saying that phrase a lot should be a hint that something else is going on?

It’s also fun to see the cope, that this must be all that free market competition.

Amjad Msad: This doesn’t make much sense. China’s market is hyper competitive. In other words, it’s the opposite of socialist. That’s why you see thinner margins and more overall dynamism than US markets.

Yes, it’s hyper competitive, and the ways in which it is not socialist are vital to its ability to function, but that hyper competition is, as I understand it, ‘not natural,’ and very much not due to the invisible hand, but rather a different highly visible one.

We couldn’t pull it off and shouldn’t try. The PCR’s strategy is a package deal, the same way America’s strategy is a package deal, and our strategy has been the most successful in world history until and except where we started shooting ourselves in the foot. They are using their advantages and we must use ours. If we try to play by their rules, especially on top of our rules, they will win.

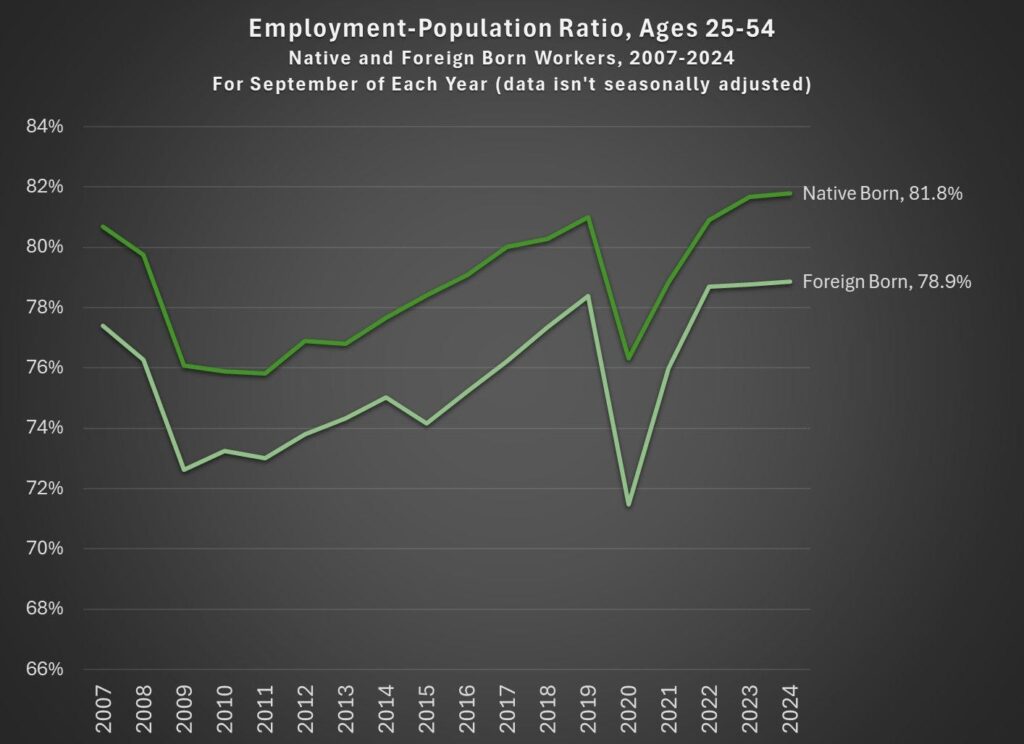

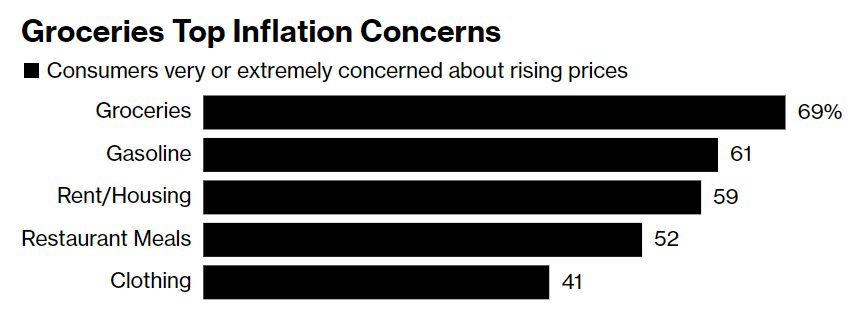

John Arnold: CA raised min wage for fast food workers 25% ($16 -> $20) and employment in the sector fell 3.2% in the first year. While I hate sectoral specific min wage laws, this is less than I’d have thought. That said, the real risk is tech substitutes for labor over long term, not year 1.

It’s interesting to see people’s biases as they respond to this paper.

Claude estimates 70% of employees were previously near minimum wage and only maybe 10% were previously over $20. It estimates the average wage shock at around 14%, although this is probably an underestimate due to spillover effects (as in, you have to adjust higher wages so that rank orders are preserved). If this was a more than 14% raise and employment only fell 3.2%, then on its face that is a huge win.

You then have to account for effects on things like hours, overtime and other work conditions, and for long term effects being larger than short term effects, since a lot of investments are locked in and adjustments take time. But I do think that this is a win for ‘minimum wage increases are not as bad for employment as one would naively think and can be welfare enhancing for the workers,’ of course it makes things worse for employers and customers.

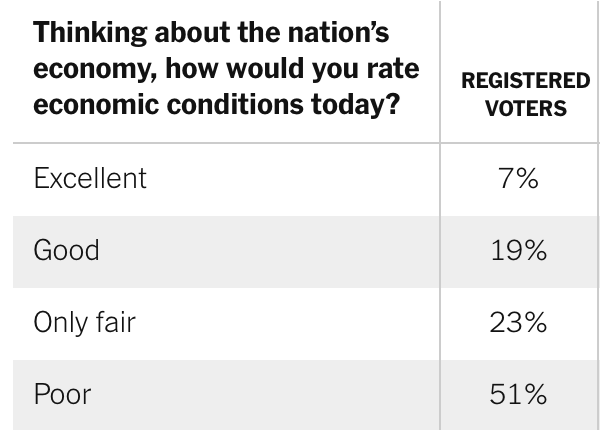

A new report from the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity (uh huh) claims 60% of Americans cannot afford a ‘minimal quality of life.’

This is the correct reaction:

Zac Hill: This is just obviously false, though.

Daniel Eth: Okay, so… this “analysis” is obvious bullshit.

I mean, obviously. Are you saying the median American household can’t afford a ‘minimal quality of life’? That’s Obvious Nonsense. Here’s a few more details, I guess:

Megan Cerullo (CBS): LISEP tracks costs associated with what the research firm calls a “basket of American dream essentials.”

…

The Ludwig Institute also says that the nation’s official unemployment rate of 4.2% greatly understates the level of economic distress around the U.S. Factoring in workers who are stuck in poverty-wage jobs and people who are unable to find full-time employment, the U.S. jobless rate now tops 24%, according to LISEP, which defines these groups as “functionally unemployed.”

Claiming the ‘real unemployment rate’ is 24% is kind of a giveaway. So is saying that your ‘minimal quality of life’ costs $120,302 for a family of four, sorry what in hell? Looking at their methodology table of contents tells you a lot about what are they even measuring.

Luca Dellanna: The study considered necessary for “Minimal Quality of Life”, I kid you not, attendance of two MLB games per year per person.

Do these charlatans hope no one reads their studies?

That’s not quite fair, the MLB games and six movies a year are a proxy for ‘basic leisure,’ but that kind of thing is happening throughout.

I love this: Businesses ‘setting traps’ for private equity by taking down their website, so Private Equity Guy says ‘oh I can get a big win by giving them a website’ and purchases your business, but the benefits of your (previously real) website are already priced in. You don’t even have to fool them, they’ll fool themselves for you:

Lauren Balik: One of the biggest hacks for small business owners is removing your website in order to sell your company at a premium.

For example, I used to have a website, then I took it down and all of a sudden I was getting legitimate, fat offers to buy my business.

See, private equity people are lazy as hell. They get data from databases showing revenue proxies, run rate estimates, all kinds of ZoomInfo crap, etc. and they are willing to pay large premiums for easy, quick wins.

What’s the easiest, quickest win? Making a website for a business that has no website.

“Wow, this business is doing $1.5M a year and $500k EBITDA with no website. Imagine if we made a website! We could get this to $3M gross and $1.5M EBITDA overnight!”

Because private equity people are narcissistic, they don’t even consider that a small business owner may have outfoxed them and purposely taken down their website to set a trap.

You should be doing less, not more, and baiting snares for PE.

Hunter: Maybe a few fake bad reviews about the owners aren’t properly leveraging technology.

Mark Le Dain (from another thread): If you are planning to sell a plumbing company to PE make sure you get rid of the website before selling it They love to say “and I can’t even imagine what it will be like once we add a website and a CRM”

Lauren Balik: It even happens at scale. Subway pulled this on Roark lmfao.

People think I make stuff up. All throughout late 2023 and early 2024 Subway started breaking their own website and making it unusable for customers as Subway was trying to put pressure on Ayn Rand-inspired PE firm Roark Capital to close the acquisition.

Every time the website lost sales or went down it put more pressure on Roark to close the deal, which was finally completed in April 2024.

Should GDP include defense spending? The argument is it is there to enable other goods and services, it is not useful per se. To which I say, tons of other production is also there to enable other goods and services. Even if we’re talking purely about physical security, should we not count locksmiths or smoke alarms or firefighting? Should we not count bike helmets? Should we not count advertising? Should we not count goods that are not useful, or are positional or zero-sum? Lawyers? Accountants? All investments? Come on.

It is fine to say ‘there is a measure of non-defense production and it is more meaningful as a measure of living standards,’ sure, but that is not GDP. But if we are measuring living standards, a much bigger issue is that cost is very different from consumer surplus, especially regarding the internet and soon also AI.

Roon notices that as Taleb told us there is almost never a shortage that is not followed by a glut, and wonders why we ever need to panic about lack of domestic production if others want to subsidize our consumption. The answer is mostly mumble mumble politics, of course, except for certain strategically vital things we might lose access to (e.g. semiconductors) or where it’s the government that’s stopping us from producing.

Discussion about this post

Economics Roundup #6 Read More »