NASA’s first medical evacuation from space ends with on-target splashdown

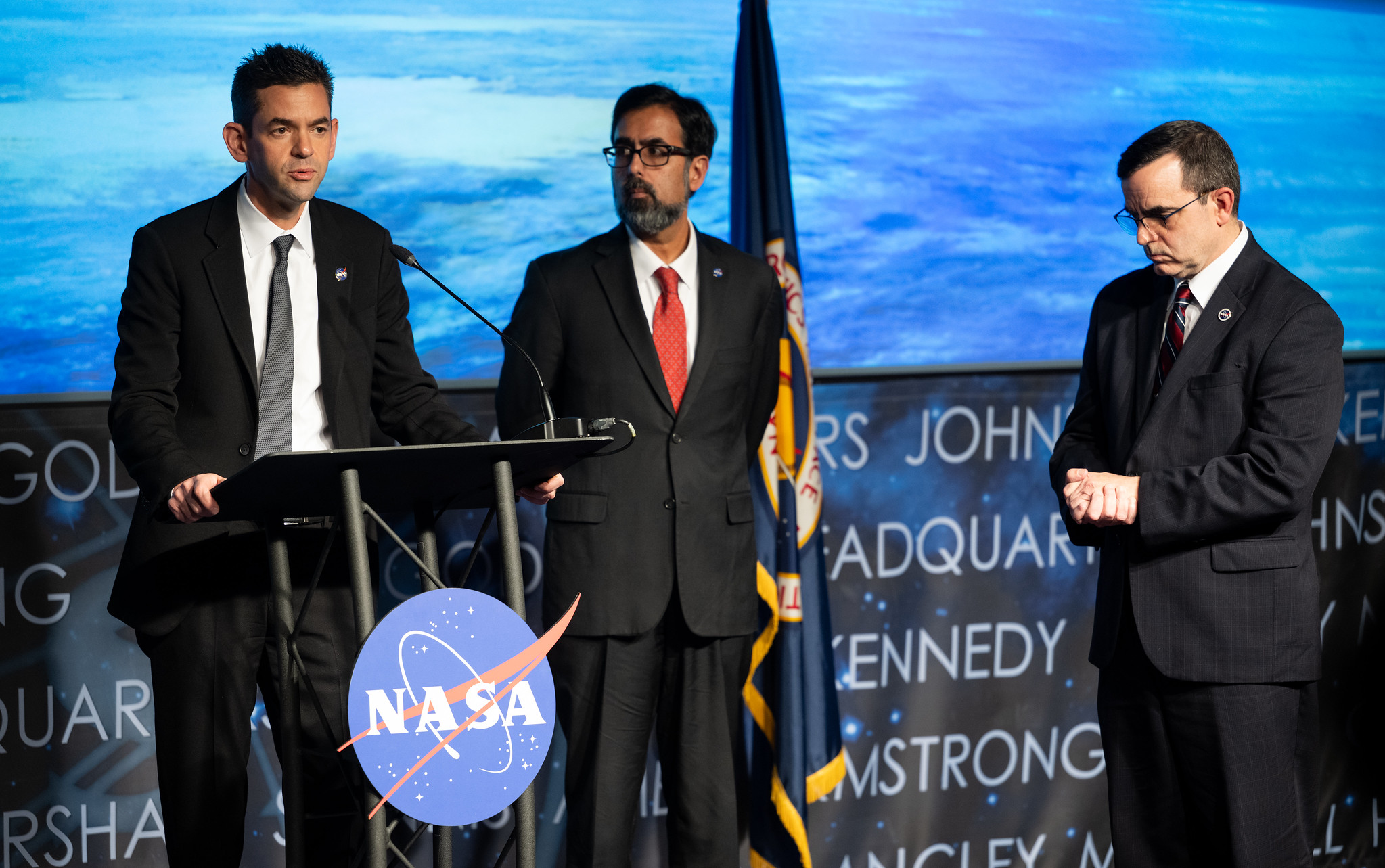

“Because the astronaut is absolutely stable, this is not an emergent evacuation,” said James “JD” Polk, NASA’s chief medical officer, in a press conference last week. “We’re not immediately disembarking and getting the astronaut down.”

Amit Kshatriya, the agency’s associate administrator, called the situation a “controlled medical evacuation” in a briefing with reporters.

But without a confirmed diagnosis of the astronaut’s medical issue, there was some “lingering risk” for the astronaut’s health if they remained in orbit, Polk said. That’s why NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman and his deputies agreed to call an early end to the Crew-11 mission.

A first for NASA

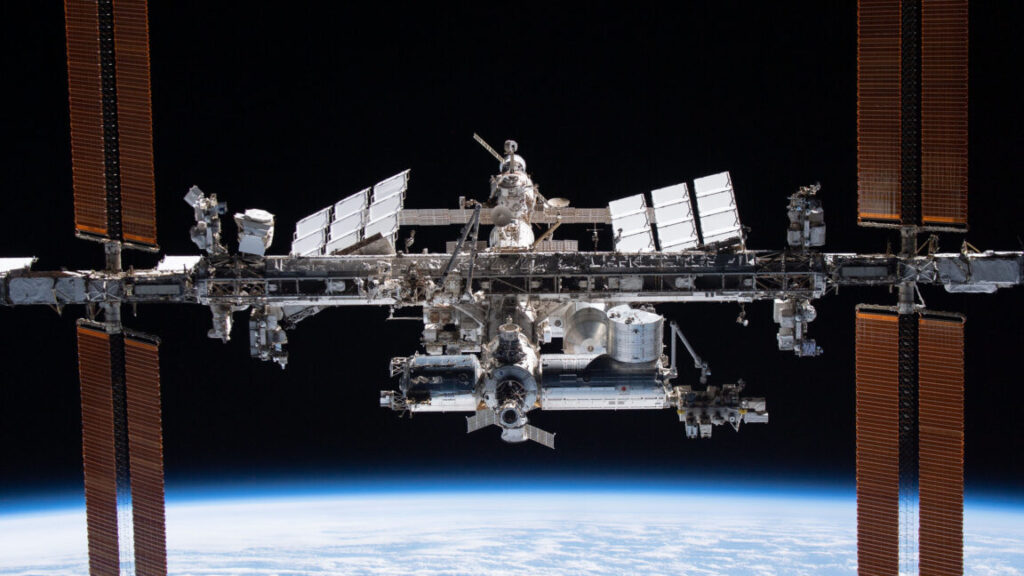

The Crew-11 mission launched on August 1 and was supposed to stay on the space station until around February 20, a few days after the scheduled arrival of SpaceX’s Crew-12 mission with a team of replacement astronauts. But the early departure means the space station will operate with a crew of three until the launch of Crew-12 next month.

NASA astronaut Chris Williams will be the sole astronaut responsible for maintaining the US segment of the station. Russian cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergey Mikayev launched with Williams in November on a Russian Soyuz vehicle. The Crew Dragon was the lifeboat for all four Crew-11 astronauts, so standard procedure called for the entire crew to return with the astronaut suffering the undisclosed medical issue.

The space station regularly operated with just three crew members for the first decade of its existence. The complex has been permanently staffed since 2000, sometimes with as few as two astronauts or cosmonauts. The standard crew size was raised to six in 2009, then to seven in 2020.

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon Endeavour spacecraft descends toward the Pacific Ocean under four main parachutes. Credit: NASA

Williams will have his hands full until reinforcements arrive. The scaled-down crew will not be able to undertake any spacewalks, and some of the lab’s science programs may have to be deferred to ensure the crew can keep up with maintenance tasks.

This is the first time NASA has called an early end to a space mission for medical reasons, but the Soviet Union faced similar circumstances several times during the Cold War. Russian officials cut short an expedition to the Salyut 7 space station in 1985 after the mission’s commander fell ill in orbit. A similar situation occurred in 1976 with the Soyuz 21 mission to the Salyut 5 space station.

NASA’s first medical evacuation from space ends with on-target splashdown Read More »