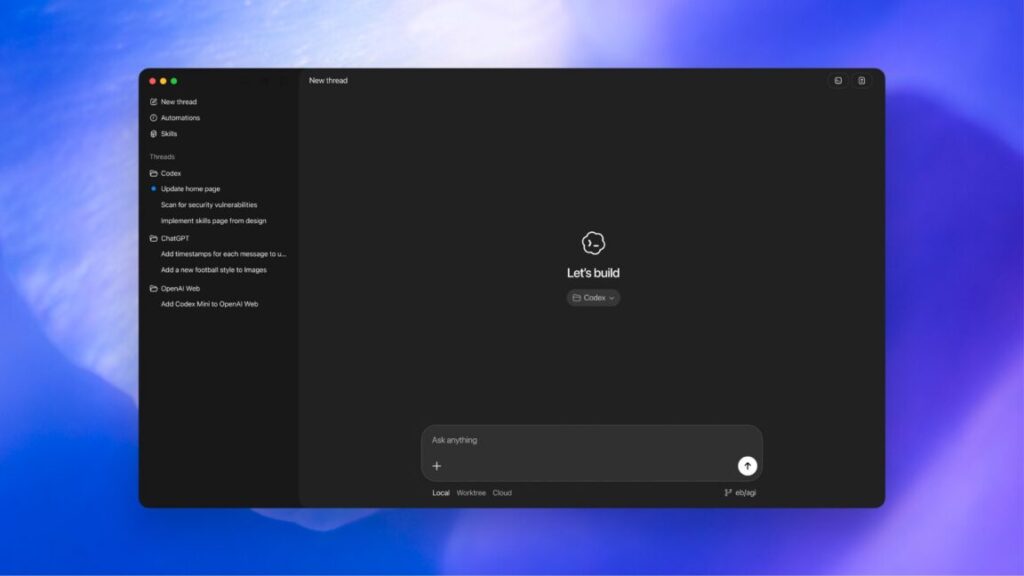

While we wait for wisdom, OpenAI releases a research preview of a new software engineering agent called Codex, because they previously released a lightweight open-source coding agent in terminal called Codex CLI and if OpenAI uses non-confusing product names it violates the nonprofit charter. The promise, also reflected in a number of rival coding agents, is to graduate from vibe coding. Why not let the AI do all the work on its own, typically for 1-30 minutes?

The answer is that it’s still early days, but already many report this is highly useful.

Sam Altman: today we are introducing codex.

it is a software engineering agent that runs in the cloud and does tasks for you, like writing a new feature of fixing a bug.

you can run many tasks in parallel.

it is amazing and exciting how much software one person is going to be able to create with tools like this. “you can just do things” is one of my favorite memes;

i didn’t think it would apply to AI itself, and its users, in such an important way so soon.

OpenAI: Today we’re launching a research preview of Codex: a cloud-based software engineering agent that can work on many tasks in parallel. Codex can perform tasks for you such as writing features, answering questions about your codebase, fixing bugs, and proposing pull requests for review; each task runs in its own cloud sandbox environment, preloaded with your repository.

Codex is powered by codex-1, a version of OpenAI o3 optimized for software engineering. It was trained using reinforcement learning on real-world coding tasks in a variety of environments to generate code that closely mirrors human style and PR preferences, adheres precisely to instructions, and can iteratively run tests until it receives a passing result.

…

Once Codex completes a task, it commits its changes in its environment. Codex provides verifiable evidence of its actions through citations of terminal logs and test outputs, allowing you to trace each step taken during task completion. You can then review the results, request further revisions, open a GitHub pull request, or directly integrate the changes into your local environment. In the product, you can configure the Codex environment to match your real development environment as closely as possible.

Codex can be guided by AGENTS.md files placed within your repository. These are text files, akin to README.md, where you can inform Codex how to navigate your codebase, which commands to run for testing, and how best to adhere to your project’s standard practices. Like human developers, Codex agents perform best when provided with configured dev environments, reliable testing setups, and clear documentation.

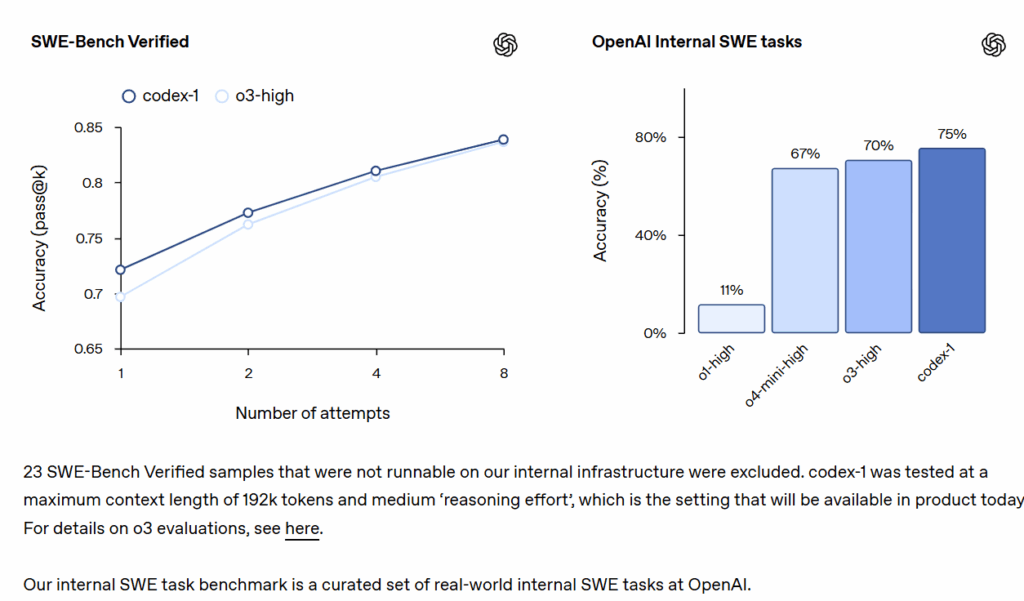

On coding evaluations and internal benchmarks, codex-1 shows strong performance even without AGENTS.md files or custom scaffolding.

All code is provided via GitHub repositories. All codex executions are sandboxed in the cloud. The agent cannot access external websites, APIs or other services. Afterwards you are given a comprehensive log of its actions and changes. You then choose to get the code via pull requests.

Note that while it lacks internet access during its core work, it can still install dependencies before it starts. But there are reports of struggles with its inability to install dependencies while it runs, which seems like a major issue.

Inability to access the web also makes some things trickier to diagnose, figure out or test. A lot of my frustration with AI coding is everything I want to do seems to involve interacting with persnickety websites.

This is a ‘research preview,’ and the worst Codex will ever be, although it might temporarily get less affordable once the free preview period ends. It does seem like they have given this a solid amount of thought and taken reasonable precautions.

The question is, when is this a better way to code than Cursor or Claude Code, and how does this compare to existing coding agents like Devin?

It would have been easy, given everything that happened, for OpenAI to have said ‘we do not need to give you a system card addendum, this is in preview and not a fully new model, etc.’ It is thus to their credit that they gave us the card anyway. It is short, but there is no need for it to be long.

As you would expect, the first thing that stood out was 2.3, ‘falsely claiming to have completed a task it did not complete.’ This seems to be a common pattern in similar models, including Claude 3.7.

I believe this behavior is something you want to fight hard to avoid having the AI learn in the first place. Once the AI learns to do this, it is difficult to get rid of it, but it wouldn’t learn it if you weren’t rewarding it during training. It is avoidable in theory. Is it avoidable in practice? I don’t know if the price is worthwhile, but I do know it’s worth a lot to avoid it.

OpenAI does indeed try, but with positive action rather than via negativa. Their plan is ensuring that the model is penalized for producing results inconsistent with its actions, and rewarded for acknowledging limitations. Good. That was a big help, going from 15% to 85% chance of correctly stating it couldn’t complete tasks. But 85% really isn’t 99%.

As in, I think if you include some things that push against pretending to solve problems, that helps a lot (hence the results here), but if you also have other places that pretending is rewarded, there will be a pattern, and then you still have a problem, and it will keep getting bigger. So instead, track down every damn place in which the AI could get away with claiming to have solved a task during training without having solved it, and make sure you always catch all of them. I know this is asking a lot.

They solve prompt injecting via network sandbagging. That definitely does the job for now, but also they made sure that prompt injections inside the coding environment also mostly failed. Good.

Finally we have the preparedness team affirming that the model did not reach high risk in any categories. I’d have liked to see more detail here, but overall This Is Fine.

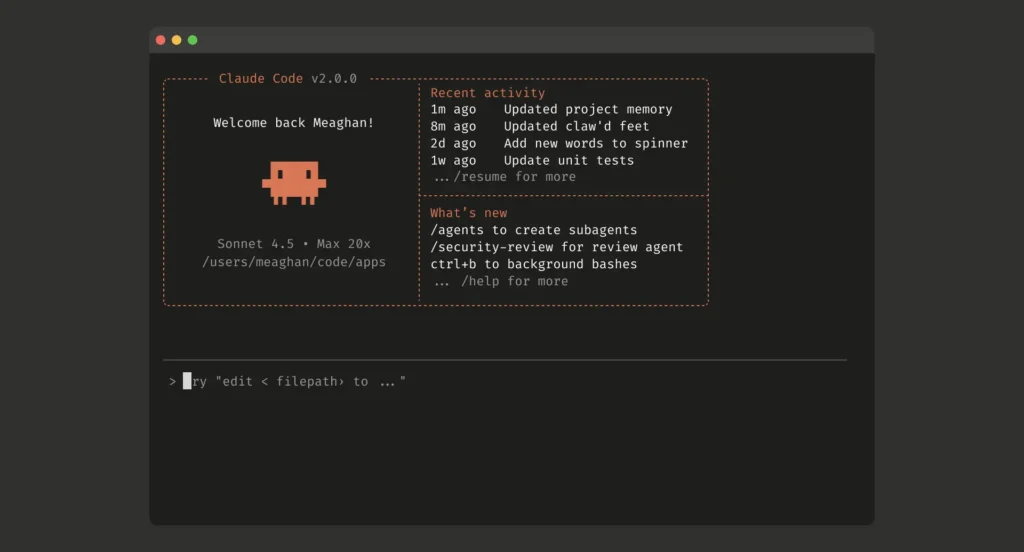

Want to keep using the command line? OpenAI gives you codex-1, a variant of o4-mini, as an upgrade. They’re also introducing a simpler onboarding process for it and offering some free credits.

These look like a noticeable improvement over o4-mini-high and even o3-high. Codex-mini-latest will be priced at $1.50/$6 per million with a 75% prompt caching discount. They are also setting a great precedent by sharing the system message.

Greg Brockman speculates that over time the ‘local’ and ‘remote’ coding agents will merge. This makes sense. Why shouldn’t the local agent call additional remote agents to execute subtasks? Parallelism for the win. Nothing could possibly go wrong.

Immediate reaction to Codex was relatively muted. It takes a while for people to properly evaluate this kind of tool, and it is only available to those paying $200/month.

What feedback we do have is somewhat mixed. Cautious optimism, especially for what a future version could be, seems like the baseline.

Codex is the combination of an agent implementation with the underlying model. Reports seem to be consistent with the underlying model and async capabilities being excellent and those both matter a lot, but with the implementation needing work and being much less practically useful than rival agents, requiring more hand holding, having less clean UI and running slower.

That makes Codex in its current state a kind of ‘AI coding agent for advanced power users.’ You wouldn’t use the current Codex over the competition unless you understood what you were doing, and you wanted to do a lot of it.

The future of Codex looks bright. OpenAI in many senses started with ‘the hard part’ of having a great model and strong parallelism. The things still missing seem easily fixable over time.

One must also keep an eye out that OpenAI (especially via Greg Brockman) is picking out and amplifying positive feedback. It’s not yet clear how much of an upgrade this is over existing alternatives, especially as most reports don’t compare Codex to its rivals. That’s one reason I like to rely on my own Twitter reaction threads.

Then there’s Jules, Google’s coding assistant, which according to multiple sources is coming soon. Google will no doubt once again Fail Marketing Forever, but it seems highly plausible that Jules could be a better tool, and almost certain it will have a cheaper price tag.

What can it do?

Whatever those things are, it can do them fully in parallel. People seem to be underestimating this aspect of coding agents.

Alex Halliday: The killer feature of OpenAI Codex is parallelism.

Browser-based work is evolving: from humans handling tasks one tab at a time, to overseeing multiple AI agent tabs, providing feedback as needed.

The most important thing is the Task Relevant Maturity of these systems. You need to understand for which tasks systems like Codex can be used which is function of model capability and error tolerance. This is the “opportunity zone” for all AI systems, including ours @AirOpsHQ.

It can do legacy project migrations.

Flavio Adamo: I asked Codex to convert a legacy project from Python 2.7 to 3.11 and from Django 1.x to 5.0

It literally took 12 minutes. If you know, that’s usually weeks of pain. This is actually insane.

Haider: how much manual cleanup or review did it need after that initial pass?

Flavio Adamo: Not much, actually. Just a few Docker issues, solved in a couple of minutes.

Here’s Darwin Santos pumping out PRs and being very impressed.

Darwin Santos: Don’t mind us – it’s just @elvstejd and me knocking one PR after another with Codex. Thanks @embirico – @kevinweil. You weren’t joking with this being yet again a game changer.

Here’s Seconds being even more impressed, and sdmat being impressed with caveats.

0.005 Seconds: It’s incredible. The ux is mid and it’s missing features but the underlying model is so good that if you transported this to 2022 everyone would assume you have agi and put 70% of engineers into unemployment. 6 months of product engineering and it replaces teams.

It has been making insane progress in fairly complex scenarios on my personal project and I pretty effortlessly closed 7 tickets at work today. It obliterates small to medium tasks in familiar context.

Sdmat: Fantastic, though only part of what it will be and rough around the edges.

With no environment internet access, no agent search tool, and oriented to small-medium tasks it is currently a scalpel.

An excellent scalpel if you know what it is you want to cut.

Conrad Barski: this is right: it’s power is not that it can solve 50% of hard problems, it’s that it solves 99.9% of mid problems.

Sdmat: Exactly.

And mid problems comprise >90% of hard problems, so if you know what you are doing and can carve at the joints it is a very, very useful tool.

And here’s Riley Coyote being perhaps the most impressed, especially by the parallelism.

Riley Coyote: I’m *reallytrying to play it cool here but like…

I’mma just say it: Codex might be the most impressive, most *powerfulAI product I’ve ever touched. all things considered. the async ability, especially, is on another level. like it’s not just a technical ‘leap’, it’s transcendent. I’ve used basically every ai coding tool and platform out there at least once, and nothing else is in the same class. it just works, ridiculously well. and I’ll admit, I didn’t want to like it. Maybe it’s stubborn loyalty to Claude – I love that retro GUI and the no-nonsense simplicity of Claude Code. There’s still something special there and ill alway use it.

but, if I’m honest: that edge is kinda becoming irrelevant, because Codex feels like having a private, hyper-competent swarm – a crack team of 10/10 FS devs, but kinda *betteri think tbh.

it’s wild. at this rate, I might start shipping something new every single day, at least until I clear out my backlog (which, without exaggeration, is something like 35-40 ‘projects’ that are all ~70–85% done). this could not have come at a better time too. I desperately needed the combination of something like codex and much higher rate limits + a streamlined pipeline from my daily drive ai to db.

go try it out.

sidebar/tip: if you cant get over the initial hump, pop over to ai.studio.google.com and click the “build apps” button on the left hand side.

a bunch of sample apps and tools propogates and they’re actually really really really good one-click zero-shots essentially….

shits getting wild. and its only monday.

Bayram Annakov prefers Deep Research’s output for now on a sample task, but finds Codex to be promising as well, and it gets a B on an AI Product Engineer homework assignment.

Here’s Robbie Bouschery finding a bug in the first three minutes.

JB one shots a doodle jump game and gets 600k likes for the post, so clearly money well spent. Paul Couvert does the same with Gemini 2.5 although objectively the platform placement seems better in Codex’s version. Upgrade?

Reliability will always be a huge sticking point, right up until it isn’t. Being highly autonomous only matters if you can trust it.

Fleischman Mena: I’m reticent to use it on featurework: ~unchanged benchmarks & results look like o3 bolted to a SWE-bench finetune + git.

You seem to still need to baby it w/ gold-set context for decent outputs, so it’s unclear where alpha is vs. current reprompt grinds

…

It’s a nice “throw it in the bag, too” feature if you’re hitting GPT caps and don’t want to fan out to other services: But to me, it’s in the same category as task scheduling and the web agent: the “party trick” version of a better thing yet to come.

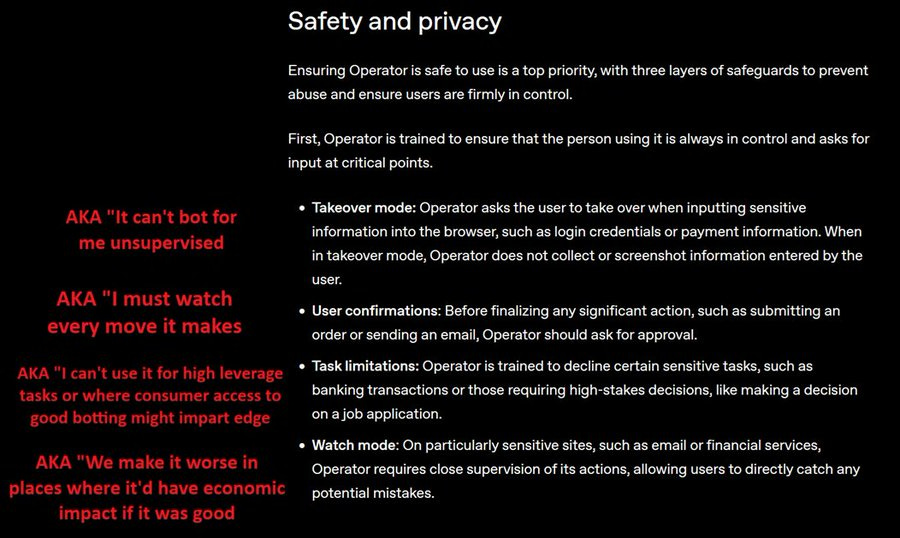

He points to a similar issue with Operator. I have access to Operator, but I don’t bother using it, largely because in many of the places where it is valuable it requires enough supervision I might as well do the job myself:

Henry: Does anyone use that ‘operator’ agent for anything?

Fleischman Mena: Not really.

Problem with web operators are that the REAL version of that product pretty much HAVE to be made by a sin-eater like the leetcode cheating startup.

Nobody wants “we build a web botting platform but it’s useless whenever lots of bots would have an impact.”

You pretty much HAVE to commit to “we’re going to sell you the ability to destroy the internet commons with bots”,

-or accept you’re only selling the “party trick” version of what this software would actually be if implemented “properly” for its users.

The few times I tried to use Operator to do something that would have been highly annoying to do myself, it fell down and died, and I decided that unless other people started reporting great results I’d rather just wait for similar agents to get better.

Alex Mizrahi reports Codex engaging in ‘busywork,’ identifying and fixing a ‘bug’ that wasn’t actually a bug.

Scott Swingle tries Codex out and compares it to Mentat. A theme throughout is that Mentat is more polished and faster, whereas Codex has to rerun a bunch of stuff. He likes o3 as the underlying model more than Sonnet 3.7, but finds the current implementation to not yet be up to par.

Lemonaut mostly doesn’t see the alpha over using some combination of Devin and Cursor/Cline, and finds it terribly finnicky and requiring hand holding in ways Cline and Devin aren’t, but does notice it solve a relatively difficult prompt. Again, that is compatible with o3 being a very good base model, but the implementation needing work.

People think about price all wrong.

Don’t think about relative price. Think about absolute benefits versus absolute price.

It doesn’t matter if ten times the price is ten times better. If ten times the price makes you 10% better, it’s an absolute steal.

Fleischman Mena: The sticking point is $2,160/year more than plus.

If you think Plus is a good deal at $240, the upgrade only makes sense if you GENUINELY believe

“This isn’t just better, it’s 10x better than plus, AND a better idea than subscribing to 9 other LLM pro plans.”

Seems dubious.

…

The $2,160 price issue is hard to ignore. that buys you ~43M o3 I/O tokens via API. War and peace is ~750k tokens. Most codebases & outputs don’t come close.

If spend’s okay, you prob do better plugging an API key into a half dozen agent competitors; you’d still come out ahead.

The dollar price, even at the $200/month a level, is chump change for a programmer, relative to a substantial productivity gain. What matters is your time and your productivity. If this improves your productivity even a few percent over rival options, and there isn’t a principal-agent problem (aka you pay the cost and someone else gets the productivity gains), then it is worthwhile. So ask whether or not it does that.

The other way this is the wrong approach is that it is only part of the $200/month package. You also get unlimited o3 and deep research use, among other products, which was previously the main attraction.

As a company, you are paying six figures for a programmer. Give them the best tools you can, whether or not this is the best tool.

This seems spot on to me:

Sully: I think agents are going to be split into 2 categories

Background & active

Background agents = stuff I don’t want to do (ux/spees doesn’t matter, but review + feedback does)

“Active agents” = things I want to do but 10x faster with agents (ux/speed matters, most apps are this)

Mat Ferrante: And I think they will be able to integrate with each other. Background leverages active one to execute quick stuff just like a user would. Active kicking off background tasks.

Sully: 100%.

Codex is currently in a weird spot. It wants to be background (or async) and is great at being async, but requires too much hand holding to let you actually ignore it for long. Once that is solved, things get a lot more interesting.