Perplexity announces “Computer,” an AI agent that assigns work to other AI agents

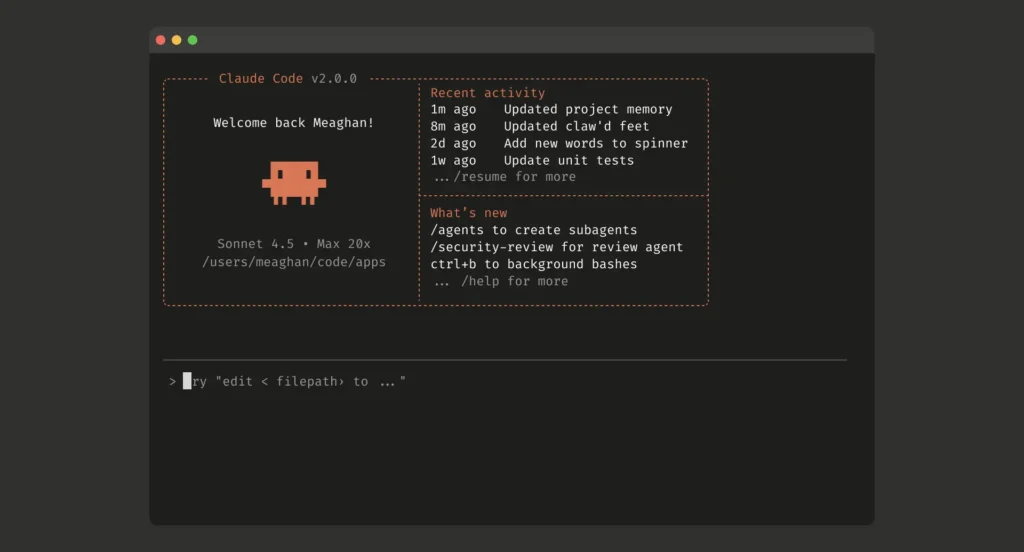

Given the right permissions and with the proper plugins, it could create, modify, or delete the user’s files and otherwise change things far beyond what most users could achieve with existing models and MCP (Model Context Protocol). Users would use files like USER.MD, MEMORY.MD, SOUL.MD, or HEARTBEAT.MD to give the tool context about its goals and how to work toward them independently, sometimes running for long stretches without direct user input.

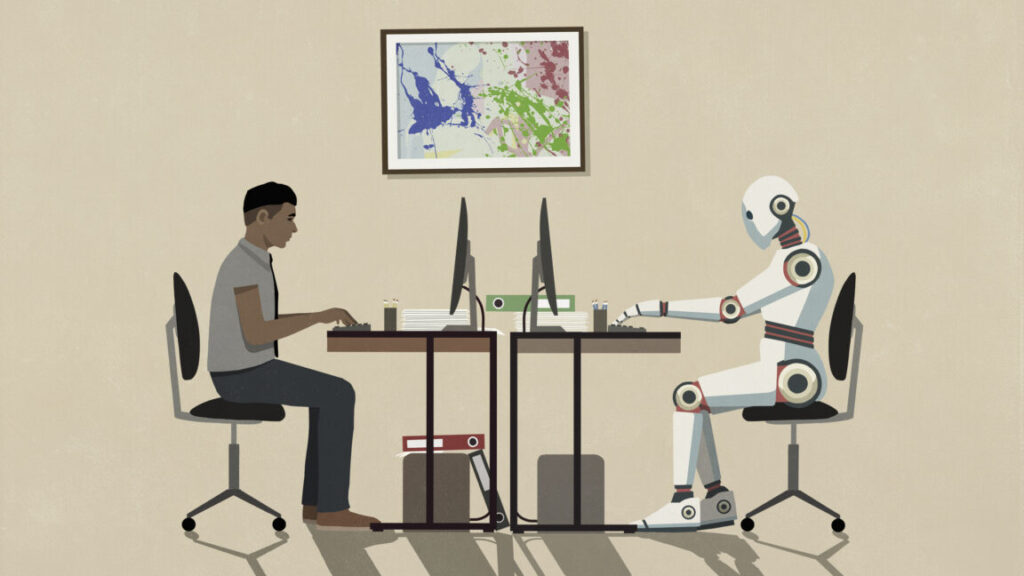

On one hand, that meant it could do impressive things—the first glimpses of the sort of knowledge work that AI boosters have been saying agentic AI would ultimately do. On the other hand, it was prone to serious errors and vulnerable to prompt injection and other security problems, in part due to a Wild West of unverified plugins.

The same toolkit that was used to create a viral Reddit clone populated by AI agents was also, at least in one case, responsible for deleting a user’s emails against her will.

Stay in your lane

Perplexity Computer aims to address those concerns in a few ways. First, its core process occurs in the cloud, not on the user’s local machine. Second, it lives within a walled garden with a curated list of integrations, in contrast to OpenClaw’s unregulated frontier.

This is, of course, an imperfect analogy, but you could say that if OpenClaw were the open web of AI agent tools, then Computer is Apple’s App Store. While you’re more limited in what you can do, you’re not trusting packages from unverified sources with access to your system.

There could still be risks, though. For one thing, LLMs make mistakes, and those could be consequential if Computer is working with data you don’t have backed up elsewhere or if you’re not verifying the outputs, for example.

Perplexity Computer aims to button up, refine, and contain the wild power of the viral OpenClaw agentic AI tool—competing with the likes of Claude Cowork—by optimizing subtasks by selecting models best suited to them.

It surely won’t be the last existing AI player to try and do this sort of thing. After all, OpenAI hired OpenClaw’s developer, with CEO Sam Altman suggesting that some of what we saw in OpenClaw will be essential to the company’s product vision moving forward.

Perplexity announces “Computer,” an AI agent that assigns work to other AI agents Read More »