Three astronauts are stuck on China’s space station without a safe ride home

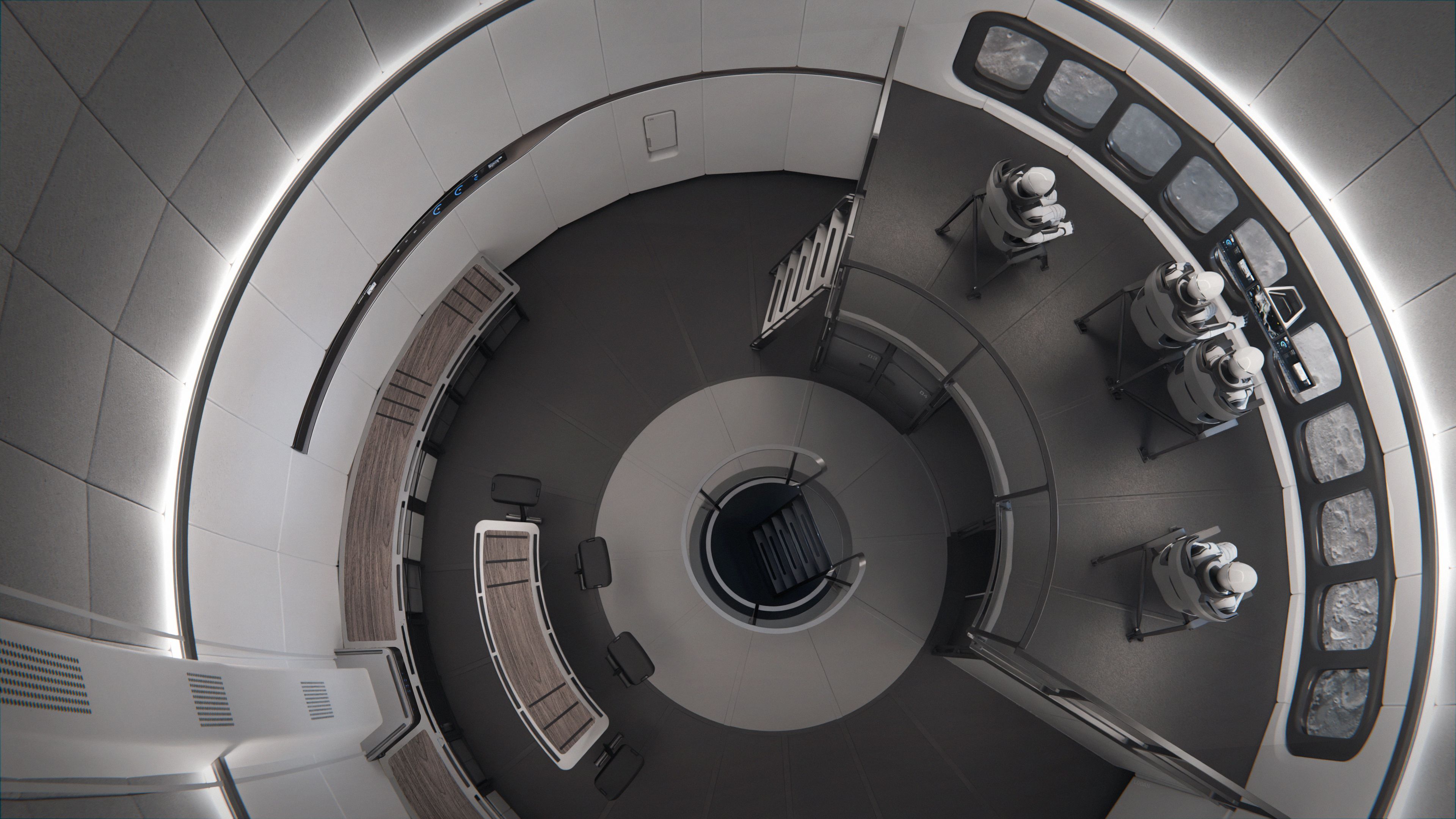

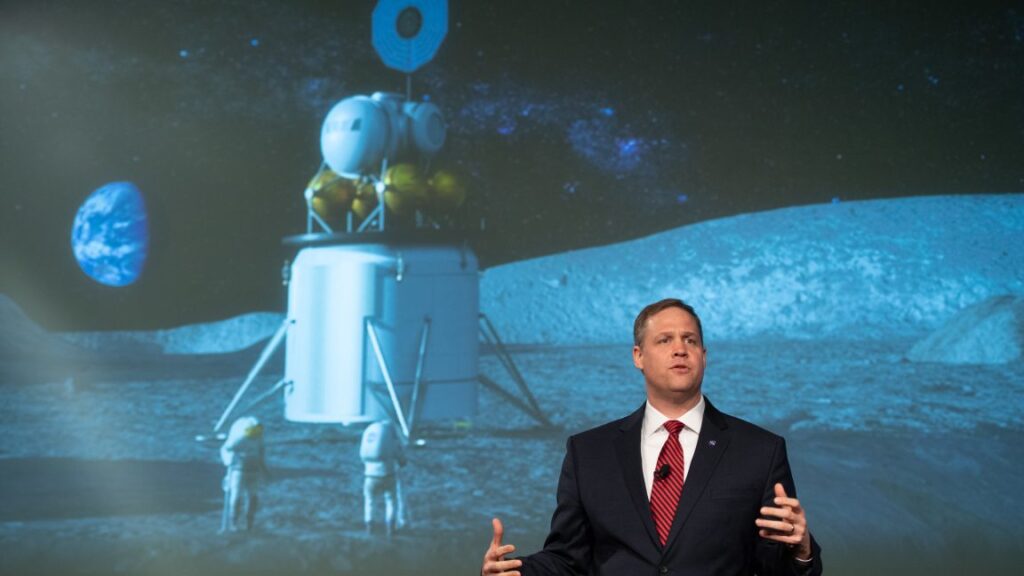

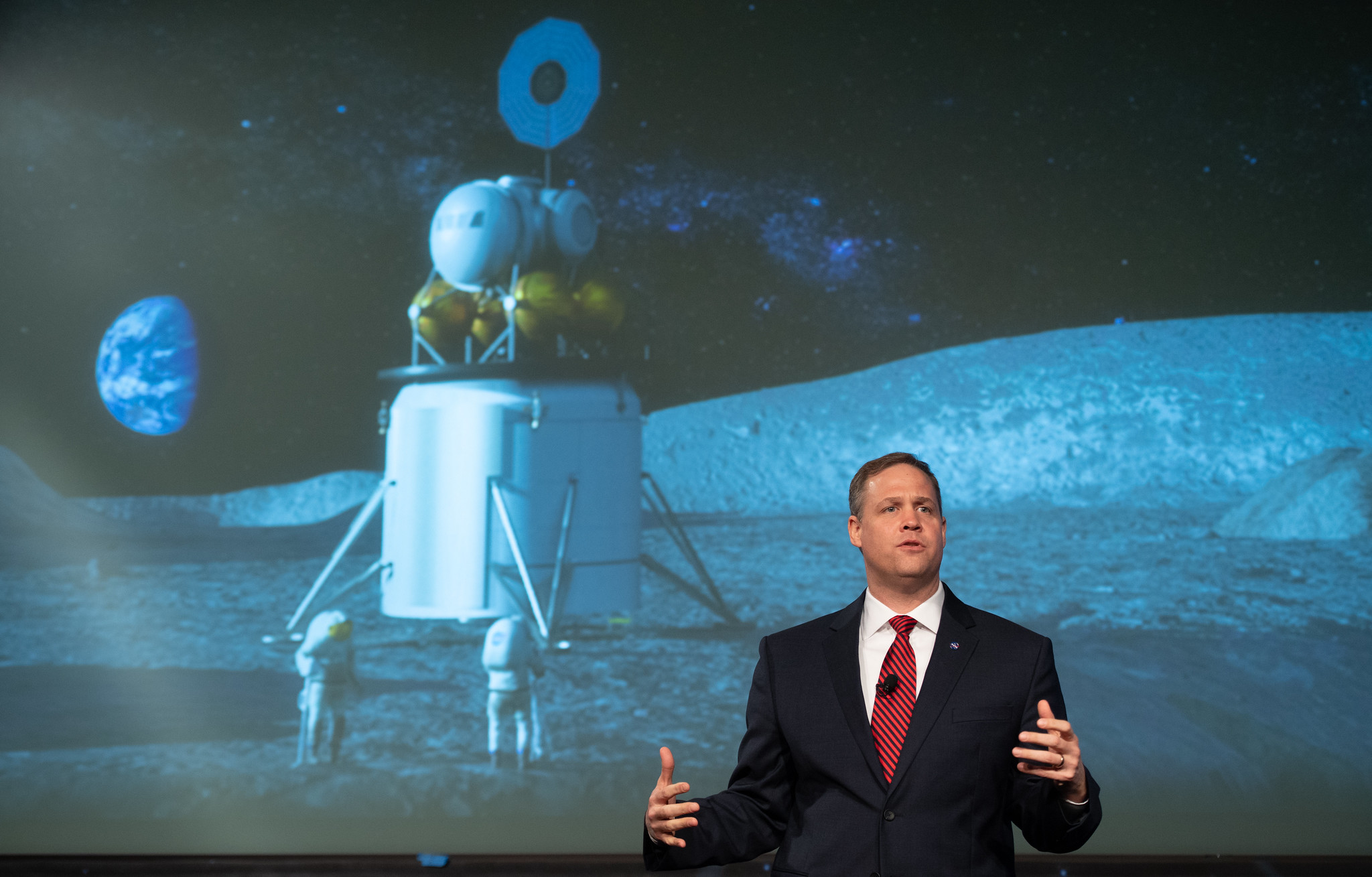

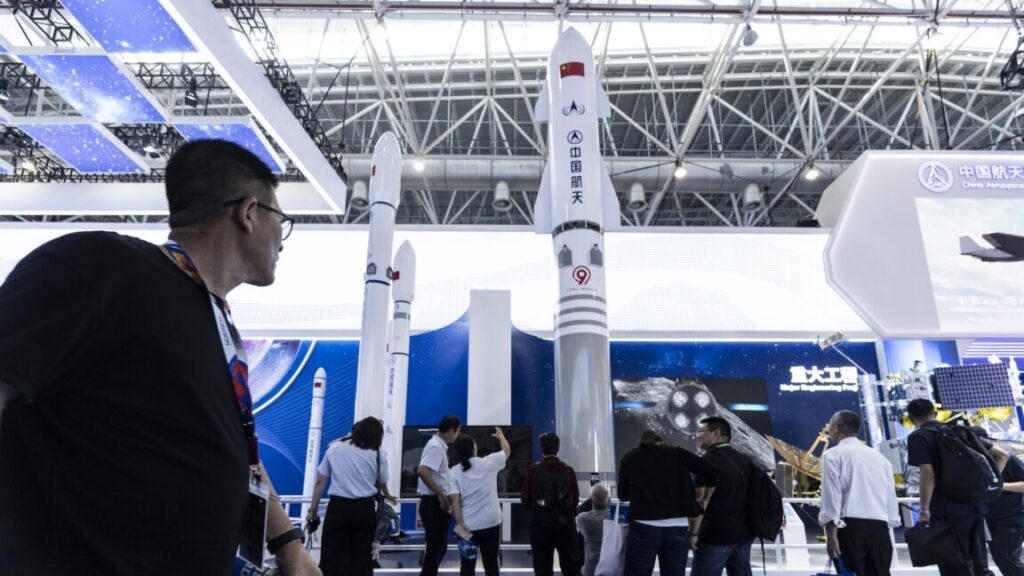

This view shows a Shenzhou spacecraft departing the Tiangong space station in 2023. Credit: China Manned Space Agency

Swapping spacecraft in low-Earth orbit

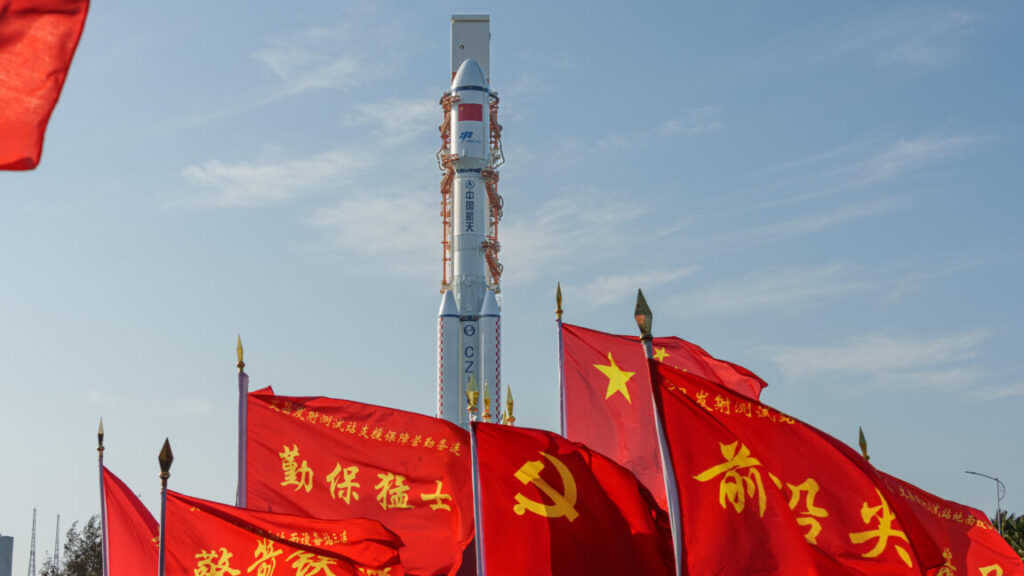

With their original spacecraft deemed unsafe, Chen and his crewmates instead rode back to Earth on the newer Shenzhou 21 craft that launched and arrived at the Tiangong station October 31. The three astronauts who launched on Shenzhou 21—Zhang Lu, Wu Fei, and Zhang Hongzhang—remain aboard the nearly 100-metric ton space station with only the damaged Shenzhou 20 craft available to bring them home.

China’s line of Shenzhou spaceships not only provide transportation to and from low-Earth orbit, they also serve as lifeboats to evacuate astronauts from the Chinese space station in the event of an in-flight emergency, such as major failures or a medical crisis. They serve the same role as Russian Soyuz and SpaceX Crew Dragon vehicles flying to and from the International Space Station.

Another Shenzhou spacecraft, Shenzhou 22, “will be launched at a later date,” the China Manned Space Agency said in a statement. Shenzhou 20 will remain in orbit to “continue relevant experiments.” The Tiangong lab is designed to support crews of six for only short periods, with longer stays of three astronauts.

Officials have not disclosed when Shenzhou 22 might launch, but Chinese officials typically have a Long March rocket and Shenzhou spacecraft on standby for rapid launch if required. Instead of astronauts, Shenzhou 22 will ferry fresh food and equipment to sustain the three-man crew on the Tiangong station.

China’s state-run Xinhua news agency called Friday’s homecoming “the first successful implementation of an alternative return procedure in the country’s space station program history.”

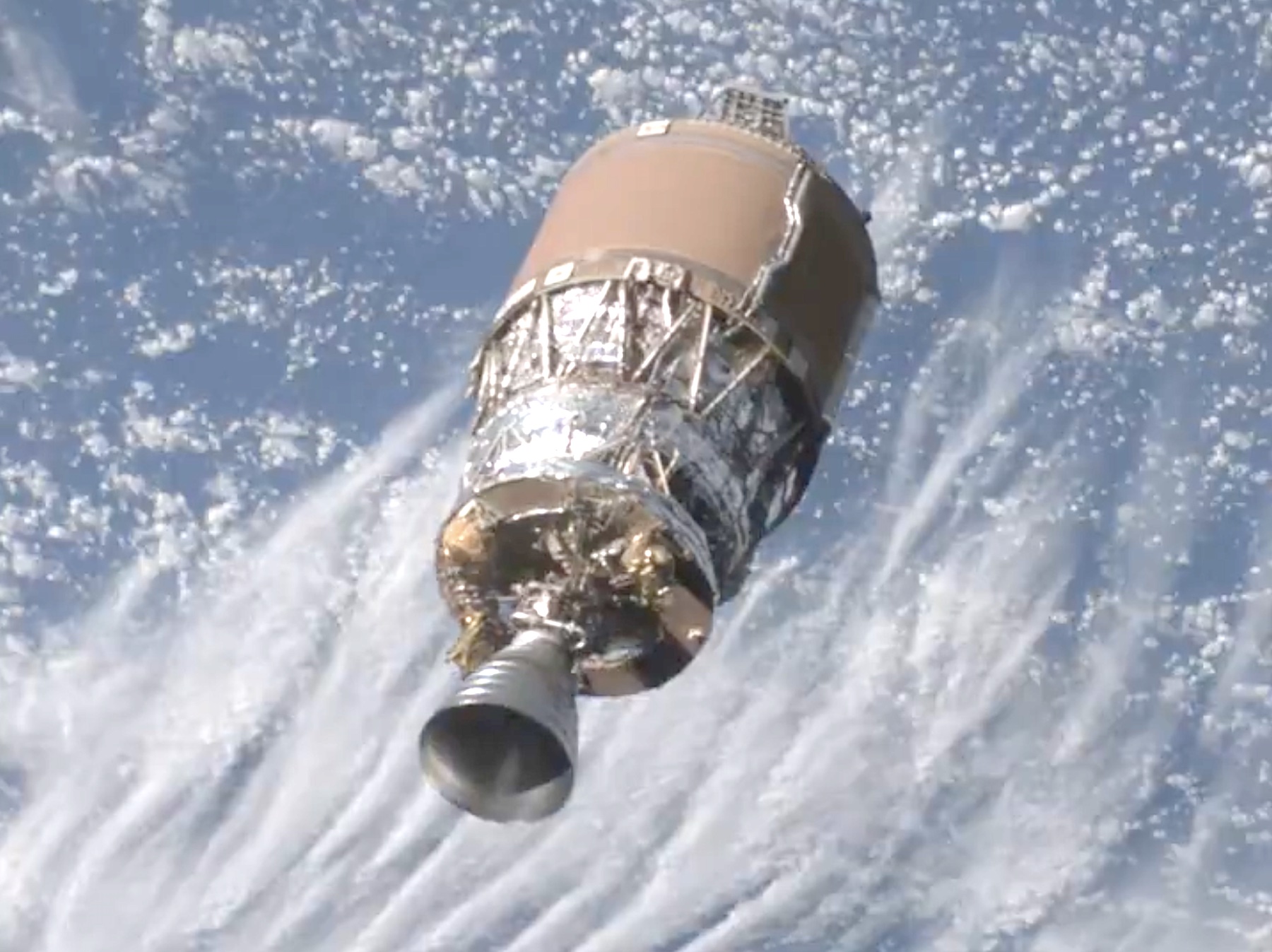

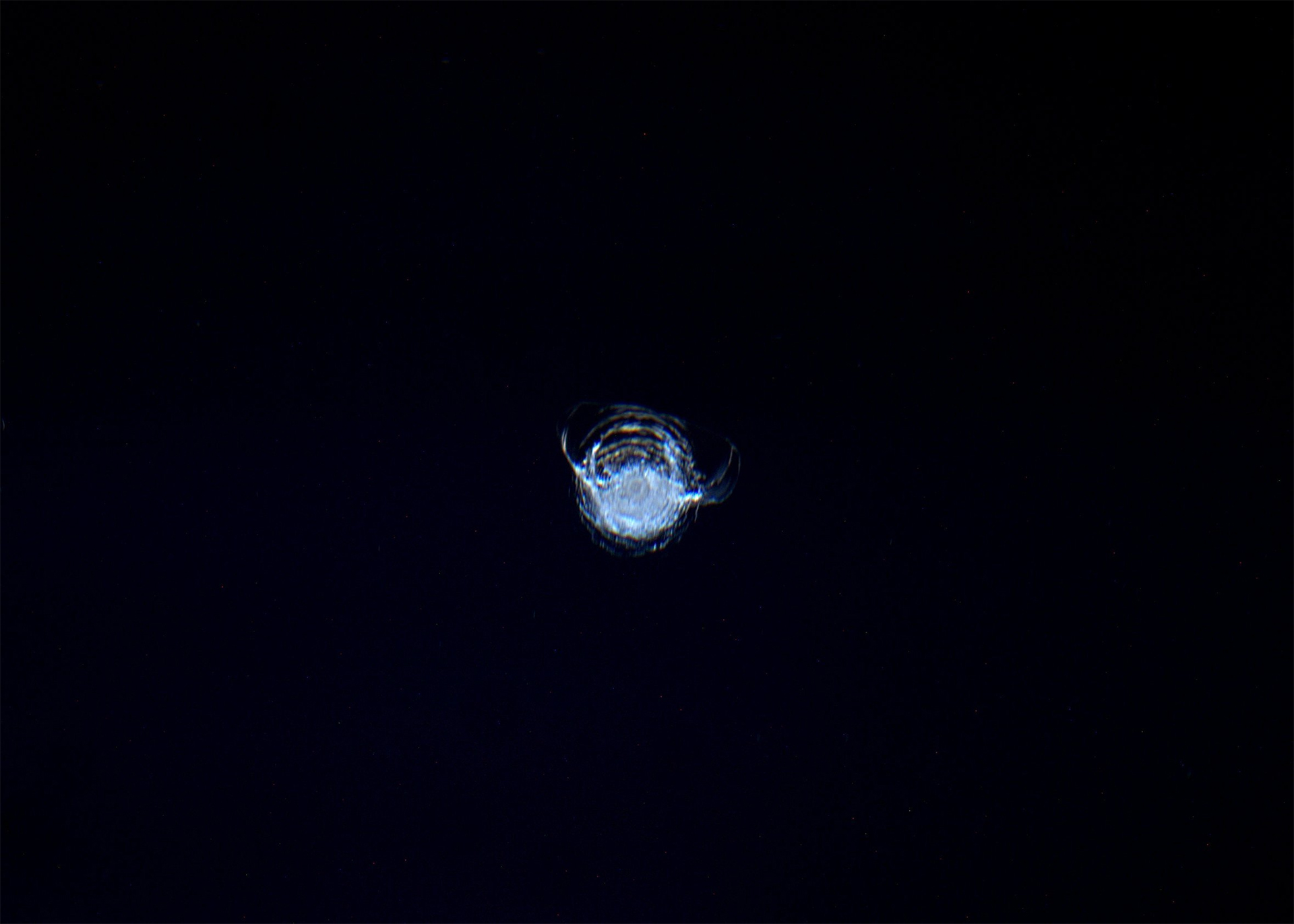

The shuffling return schedules and damaged spacecraft at the Tiangong station offer a reminder of the risks of space junk, especially tiny debris fragments that evade detection by tracking telescopes and radars. A minuscule piece of space debris traveling at several miles per second can pack a punch. Crews at the Tiangong outpost ventured outside the station multiple times in the last few years to install space debris shielding to protect the outpost.

Astronaut Tim Peake took this photo of a cracked window on the International Space Station in 2016. The 7-millimeter (quarter-inch) divot on the quadruple-pane window was gouged out by an impact of space debris no larger than a few thousandths of a millimeter across. The damage did not pose a risk to the station. Credit: ESA/NASA

Shortly after landing on Friday, ground teams assisted the Shenzhou astronauts out of their landing module. All three appeared to be in good health and buoyant spirits after completing the longest-duration crew mission for China’s space program.

“Space exploration has never been easy for humankind,” said Chen Dong, the mission commander, according to Chinese state media.

“This mission was a true test, and we are proud to have completed it successfully,” Chen said shortly after landing. “China’s space program has withstood the test, with all teams delivering outstanding performances … This experience has left us a profound impression that astronauts’ safety is really prioritized.”

Three astronauts are stuck on China’s space station without a safe ride home Read More »