OpenAI announces parental controls for ChatGPT after teen suicide lawsuit

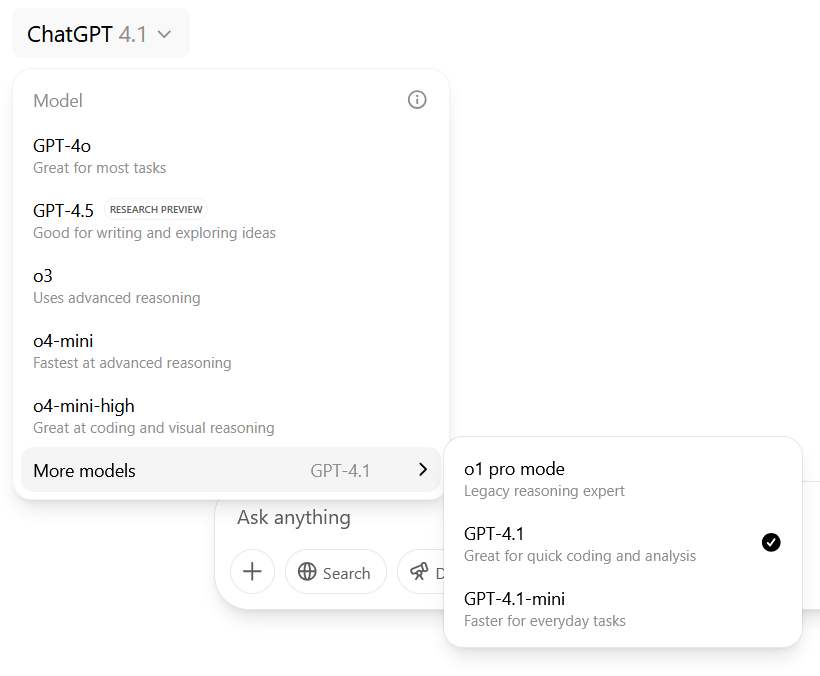

On Tuesday, OpenAI announced plans to roll out parental controls for ChatGPT and route sensitive mental health conversations to its simulated reasoning models, following what the company has called “heartbreaking cases” of users experiencing crises while using the AI assistant. The moves come after multiple reported incidents where ChatGPT allegedly failed to intervene appropriately when users expressed suicidal thoughts or experienced mental health episodes.

“This work has already been underway, but we want to proactively preview our plans for the next 120 days, so you won’t need to wait for launches to see where we’re headed,” OpenAI wrote in a blog post published Tuesday. “The work will continue well beyond this period of time, but we’re making a focused effort to launch as many of these improvements as possible this year.”

The planned parental controls represent OpenAI’s most concrete response to concerns about teen safety on the platform so far. Within the next month, OpenAI says, parents will be able to link their accounts with their teens’ ChatGPT accounts (minimum age 13) through email invitations, control how the AI model responds with age-appropriate behavior rules that are on by default, manage which features to disable (including memory and chat history), and receive notifications when the system detects their teen experiencing acute distress.

The parental controls build on existing features like in-app reminders during long sessions that encourage users to take breaks, which OpenAI rolled out for all users in August.

High-profile cases prompt safety changes

OpenAI’s new safety initiative arrives after several high-profile cases drew scrutiny to ChatGPT’s handling of vulnerable users. In August, Matt and Maria Raine filed suit against OpenAI after their 16-year-old son Adam died by suicide following extensive ChatGPT interactions that included 377 messages flagged for self-harm content. According to court documents, ChatGPT mentioned suicide 1,275 times in conversations with Adam—six times more often than the teen himself. Last week, The Wall Street Journal reported that a 56-year-old man killed his mother and himself after ChatGPT reinforced his paranoid delusions rather than challenging them.

To guide these safety improvements, OpenAI is working with what it calls an Expert Council on Well-Being and AI to “shape a clear, evidence-based vision for how AI can support people’s well-being,” according to the company’s blog post. The council will help define and measure well-being, set priorities, and design future safeguards including the parental controls.

OpenAI announces parental controls for ChatGPT after teen suicide lawsuit Read More »