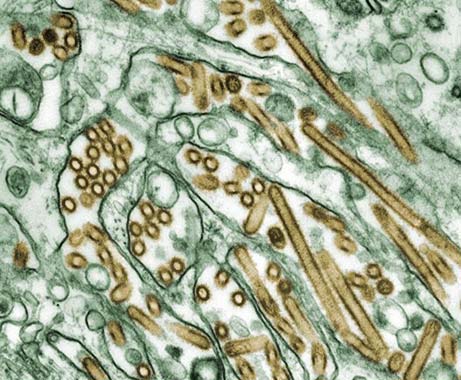

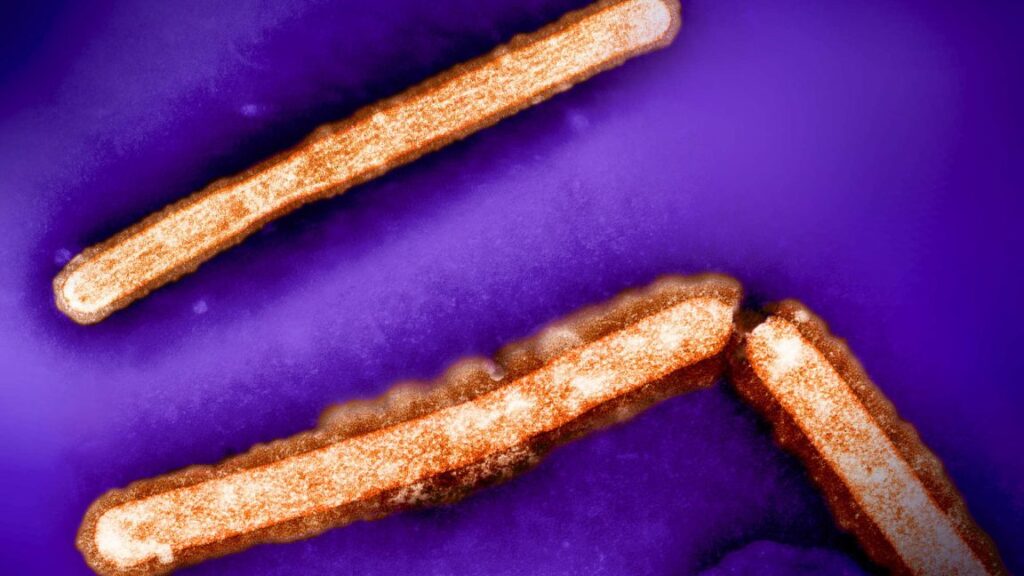

UK on alert after H5N1 bird flu spills over to sheep in world-first

In the UK, officials said further testing of the rest of the sheep’s flock has found no other infections. The one infected ewe has been humanely culled to mitigate further risk and to “enable extensive testing.”

“Strict biosecurity measures have been implemented to prevent the further spread of disease,” UK Chief Veterinary Officer Christine Middlemiss said in a statement. “While the risk to livestock remains low, I urge all animal owners to ensure scrupulous cleanliness is in place and to report any signs of infection to the Animal Plant Health Agency immediately.”

While UK officials believe that the spillover has been contained and there’s no onward transmission among sheep, the latest spillover to a new mammalian species is a reminder of the virus’s looming threat.

“Globally, we continue to see that mammals can be infected with avian influenza A(H5N1),” Meera Chand, Emerging Infection Lead at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), said in a statement. In the US, the Department of Agriculture has documented hundreds of infections in wild and captive mammals, from cats to bears, raccoons, and harbor seals.

Chand noted that, so far, the spillovers into animals have not easily transmitted to humans. For instance, in the US, despite extensive spread through the dairy industry, no human-to-human transmission has yet been documented. But, experts fear that with more spillovers and exposure to humans, the virus will gain more opportunities to adapt to be more infectious in humans.

Chand says that UKHSA and other agencies are monitoring the situation closely in the event the situation takes a turn. “UKHSA has established preparations in place for detections of human cases of avian flu and will respond rapidly with NHS and other partners if needed.”

UK on alert after H5N1 bird flu spills over to sheep in world-first Read More »