Changing one gene can restore some tissue regeneration to mice

Regeneration is a trick many animals, including lizards, starfish, and octopuses, have mastered. Axolotls, a salamander species originating in Mexico, can regrow pretty much everything from severed limbs, to eyes and parts of brain, to the spinal cord. Mammals, though, have mostly lost this ability somewhere along their evolutionary path. Regeneration persisted, in a limited number of tissues, in just a few mammalian species like rabbits or goats.

“We were trying to learn how certain animals lost their regeneration capacity during evolution and then put back the responsible gene or pathway to reactivate the regeneration program,” says Wei Wang, a researcher at the National Institute of Biological Sciences in Beijing. Wang’s team has found one of those inactive regeneration genes, activated it, and brought back a limited regeneration ability to mice that did not have it before.

Of mice and bunnies

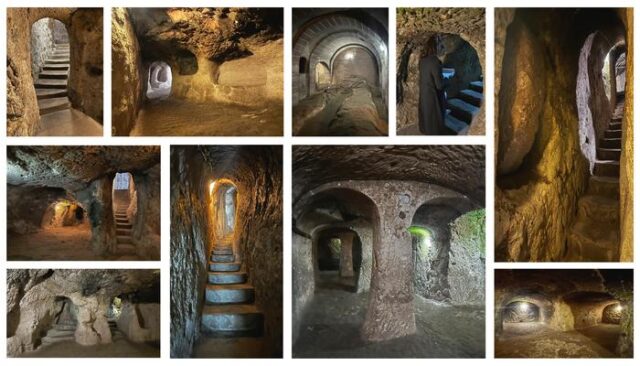

The idea Wang and his colleagues had was a comparative study of how the wound healing process works in regenerating and non-regenerating mammalian species. They chose rabbits as their regenerating mammals and mice as the non-regenerating species. As the reference organ, the team picked the ear pinna. “We wanted a relatively simple structure that was easy to observe and yet composed of many different cell types,” Wang says. The test involved punching holes in the ear pinna of rabbits and mice and tracking the wound-repairing process.

The healing process began in the same way in rabbits and mice. Within the first few days after the injury, a blastema—a mass of heterogeneous cells—formed at the wound site. “Both rabbits and mice will heal the wounds after a few days,” Wang explains. “But between the 10th and 15th day, you will see the major difference.” In this timeframe, the earhole in rabbits started to become smaller. There were outgrowths above the blastema—the animals were producing more tissue. In mice, on the other hand, the healing process halted completely, leaving a hole in the ear.

Changing one gene can restore some tissue regeneration to mice Read More »