Scientists want to treat complex bone fractures with a bone-healing gun

After examining a few candidate formulations, the team found the right material. “We used a biocompatible thermoplastic called polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite as base materials,” Lee said. Polycaprolactone was chosen because it is an FDA-approved material that degrades in the body within a few months after implantation. The hydroxyapatite, on the other hand, supports bone-tissue regeneration. Lee’s team experimented with various proportions of these two ingredients and finally nailed the formulation that checked all the boxes: It extruded at a relatively harmless 60° Celsius, the mix was mechanically sound, it adhered to the bone well, and it degraded over time.

Once the bone-healing bullets were ready, the team tested them on rabbits. Rabbits with broken femurs treated with Lee’s healing gun recovered faster than those treated with bone cement, which is the closest commercially available alternative. But there is still a lot to do before the healing gun can be tested on humans.

Skill issues

While the experiment on rabbits revealed new bone tissues forming around the implants created with the healing gun, their slow degradation of the implanted material prevented the full restoration of bone tissues. Another improvement Lee plans involves adding antibiotics to the formulation. The implant, he said, will release the drugs over time to prevent infections.

Then there’s the issue of load bearing. Rabbits are fine as test subjects, but they are rather light. “To evaluate the potential to use this technology on humans, we need to look into its long-term safety in large animal models,” Lee said.

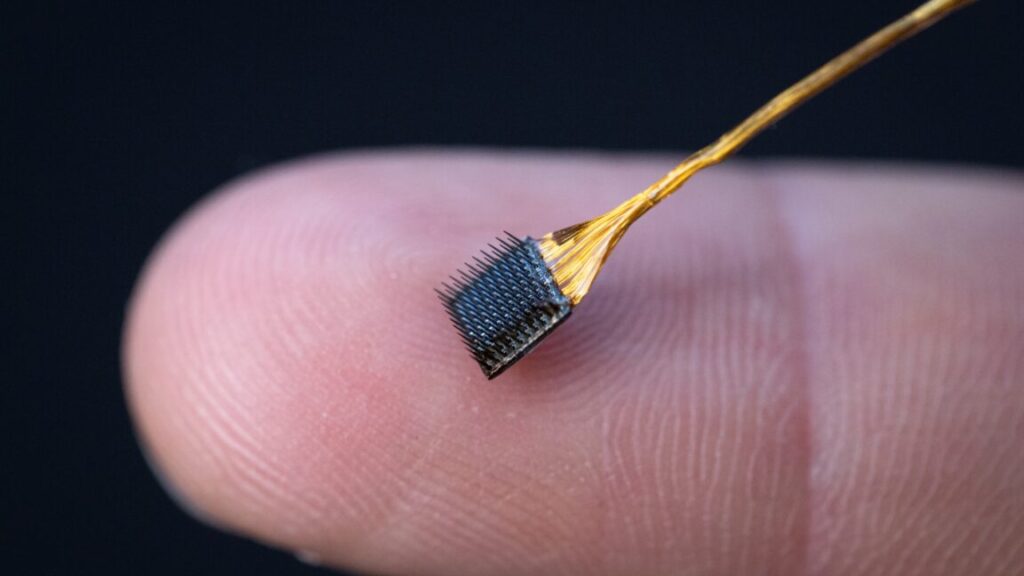

Beyond the questions about the material, the level of skill required to operate this healing gun seems rather high.

Extrusion-based 3D printers, the ones that work more or less like very advanced hot glue guns, usually use guiding rods or rails for precise printing head positioning. If those rods or rails are warped, even slightly, the accuracy of your prints will most likely suffer. Achieving comparable precision with a handheld device might be a bit difficult, even for a skilled surgeon. “It is true that the system requires practice,” Lee said. “We may need to integrate it with a guiding mechanism that would position the head of the device precisely. This could be our next-gen bone printing device.”

Device, 2025. DOI: 10.1016/j.device.2025.100873

Scientists want to treat complex bone fractures with a bone-healing gun Read More »