Tiny chips hitch a ride on immune cells to sites of inflammation

Tiny chips can be powered by infrared light if they’re near the brain’s surface.

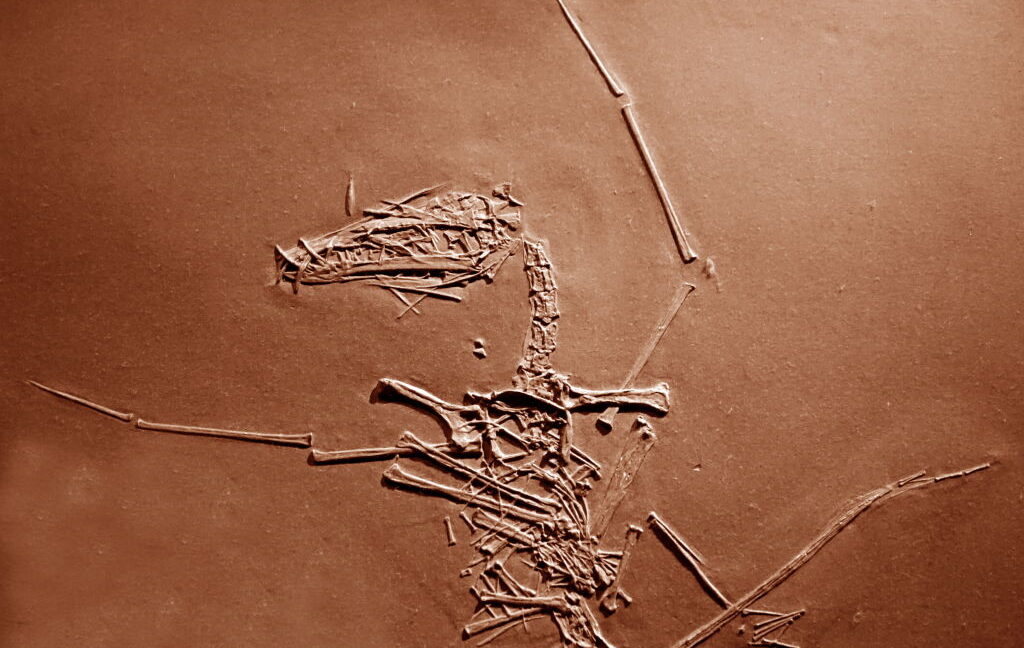

An immune cell chemically linked to a CMOS chip. Credit: Yadav, et al.

Standard brain implants use electrodes that penetrate the gray matter to stimulate and record the activity of neurons. These typically need to be put in place via a surgical procedure. To go around that need, a team of researchers led by Deblina Sarkar, an electrical engineer and MIT assistant professor, developed microscopic electronic devices hybridized with living cells. Those cells can be injected into the circulatory system with a standard syringe and will travel the bloodstream before implanting themselves in target brain areas.

“In the first two years of working on this technology at MIT, we’ve got 35 grant proposals rejected in a row,” Sarkar says. “Comments we got from the reviewers were that our idea was very impactful, but it was impossible.” She acknowledges that the proposal sounded like something you can find in science fiction novels. But after more than six years of research, she and her colleagues have pulled it off.

Nanobot problems

In 2022, when Sarkar and her colleagues gathered initial data and got some promising results with their cell-electronics hybrids, the team proposed the project for the National Institutes of Health Director’s New Innovator Award. For the first time, after 35 rejections, it made it through peer review. “We got the highest impact score ever,” Sarkar says.

The reason for that score was that her technology solved three extremely difficult problems. The first, obviously, was making functional electronic devices smaller than cells that can circulate in our blood.

“Previous explorations, which had not seen a lot of success, relied on putting magnetic particles inside the bloodstream and then guiding them with magnetic fields,” Sarkar explains. “But there is a difference between electronics and particles.” Electronics made using CMOS technology (which we use for making computer processors) can generate electrical power from incoming light in the same way as photovoltaics, as well as perform computations necessary for more intelligent applications like sensing. Particles, on the other hand, can only be used to stimulate cells to an extent.

If they ever reach those cells, of course, which was the second problem. “Controlling the devices with magnetic fields means you need to go into a machine the size of an MRI,” Sarkar says. Once the subject is in the machine, an operator looks at where the devices are and tries to move them to where they need to be using nothing but magnetic fields. Sarkar said that it’s tough to do anything other than move the particles in straight lines, which is a poor match for our very complex vasculature.

The solution her team found was fusing the electronics with monocytes, immune cells that can home in on inflammation in our bodies. The idea was that the monocytes would carry the electronics through the bloodstream using the cells’ chemical homing mechanism. This also solved the third problem: crossing the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from pathogens and toxins. Electronics alone could not get through it; monocytes could.

The challenge was making all these ideas work.

Clicking together

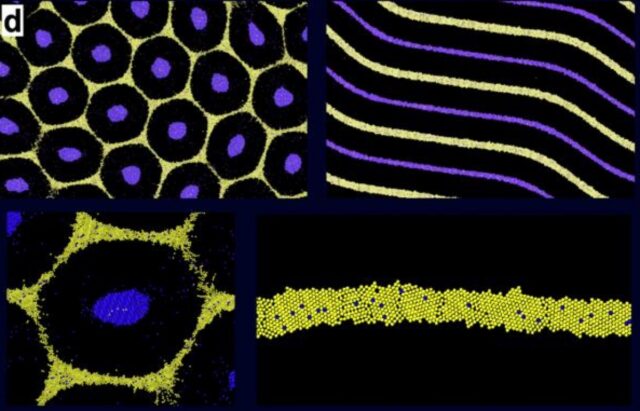

Sarkar’s team built electronic devices made of biocompatible polymer and metallic layers fabricated on silicon wafers using a standard CMOS process. “We made the devices this small with lithography, the technique used in making transistors for chips in our computers,” Sarkar explains. They were roughly 200 nanometers thick and 10 microns in diameter—that kept them subcellular, since a monocyte cell usually measures between 12 and 18 microns. The devices were activated and powered by infrared light at a wavelength that could penetrate several centimeters into the brain.

Once the devices were manufactured and taken off the wafer, the next thing to figure out was attaching them to monocytes.

To do this, the team covered the surfaces of the electronic devices with dibezocyclooctyne, a very reactive molecule that can easily link to other chemicals, especially nitrogen compounds called azides. Then Sarkar and her colleagues chemically modified monocytes to place azides on their surfaces. This way, the electronics and cells could quickly snap together, almost like Lego blocks (this approach, called click chemistry, got the 2022 Nobel Prize in chemistry).

The resulting solution of cell-electronics hybrids was designed to be biocompatible and could be injected into the circulatory system. This is why Sarkar called her concept “circulatronics.”

Of course, Sarkar’s “circulatronic” hybrids fall a bit short of sci-fi fantasies, in that they aren’t exactly literal nanobots. But they may be the closest thing we’ve created so far.

Artificial neurons

To test these hybrids in live mice, the researchers prepared a fluorescent version to make them easier to track. Mice were anesthetized first, and the team artificially created inflammation at a specific location in their brains, around the ventrolateral thalamic nucleus. Then the hybrids were injected into the veins of the mice. After roughly 72 hours, the time scientists expected would be needed for the monocytes to reach the inflammation, Sarkar and her colleagues started running tests.

It turned out that most of the injected hybrids reached their destination in one piece—the electronics mostly remained attached to the monocytes. The team’s measurements suggest that around 14,000 hybrids managed to successfully implant themselves near the neurons in the target area of the brain. Then, in response to infrared irradiation, they caused significant neuronal activation, comparable to traditional electrodes implanted via surgery.

The real strength of the hybrids, Sarkar thinks, is the way they can be tuned to specific diseases. “We chose monocytes for this experiment because inflammation spots in the brain are usually the target in many neurodegenerative diseases,” Sarkar says. Depending on the application, though, the hybrids’ performance can be adjusted by manipulating their electronic and cellular components. “We have already tested using mesenchymal stem cells for the Alzheimer’s, or T cells and other neural stem cells for tumors,” Sarkar explains.

She went on to say that her technology one day may help with placing the implants in brain regions that today cannot be safely reached through surgery. “There is a brain cancer called glioblastoma that forms diffused tumor sites. Another example is DIPG [a form of glioma], which is a terminal brain cancer in children that develops in a region where surgery is impossible,” she adds.

But in the more distant future, the hybrids can find applications beyond targeting diseases. Most of the studies that have relied on data from brain implants were limited to participants who suffered from severe brain disorders. The implants were put in their brains for therapeutic reasons, and participating in research projects was something they just agreed to do on the side.

Because the electronics in Sarkar’s hybrids can be designed to fully degrade after a set time, the team thinks this could potentially enable them to gather brain implant data from healthy people—the implants would do their job for the duration of the study and be gone once it’s done. Unless we want them to stay, that is.

“The ease of application can make the implants feasible in brain-computer interfaces designed for healthy people,” Sarkar argues. “Also, the electrodes can be made to work as artificial neurons. In principle, we could enhance ourselves—increase our neuronal density.”

First, though, the team wants to put the hybrids through a testing campaign on larger animals and then get them FDA-approved for clinical trials. Through Cahira Technologies, an MIT spinoff company founded to take the “circulatronics” technology to the market, Sarkar wants to make this happen within the next three years.

Nature Biotechnology, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-025-02809-3

Tiny chips hitch a ride on immune cells to sites of inflammation Read More »