Saturn’s moon Titan has shorelines that appear to be shaped by waves

Surf the moon —

The liquid hydrocarbon waves would likely reach a height of a meter.

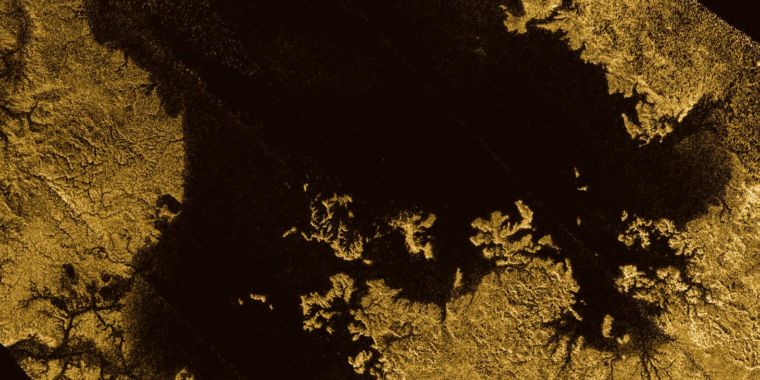

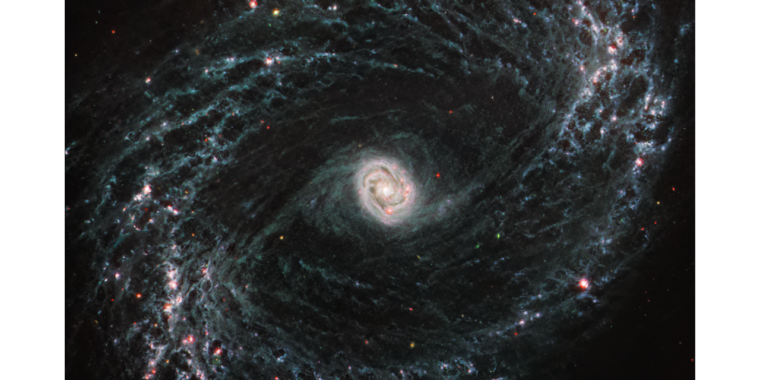

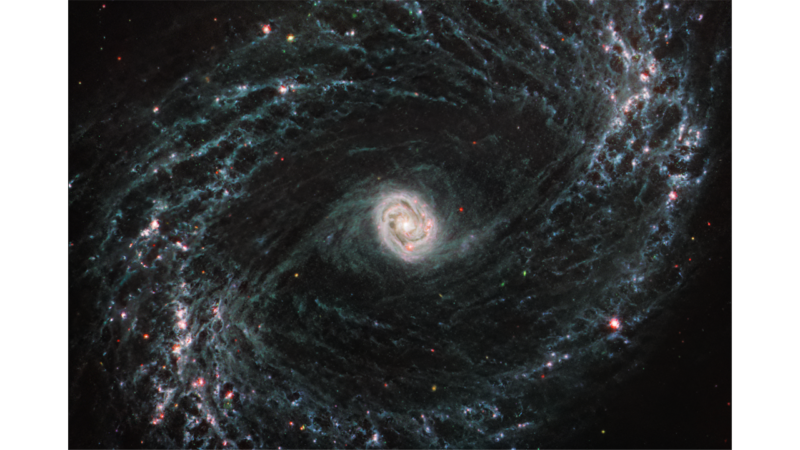

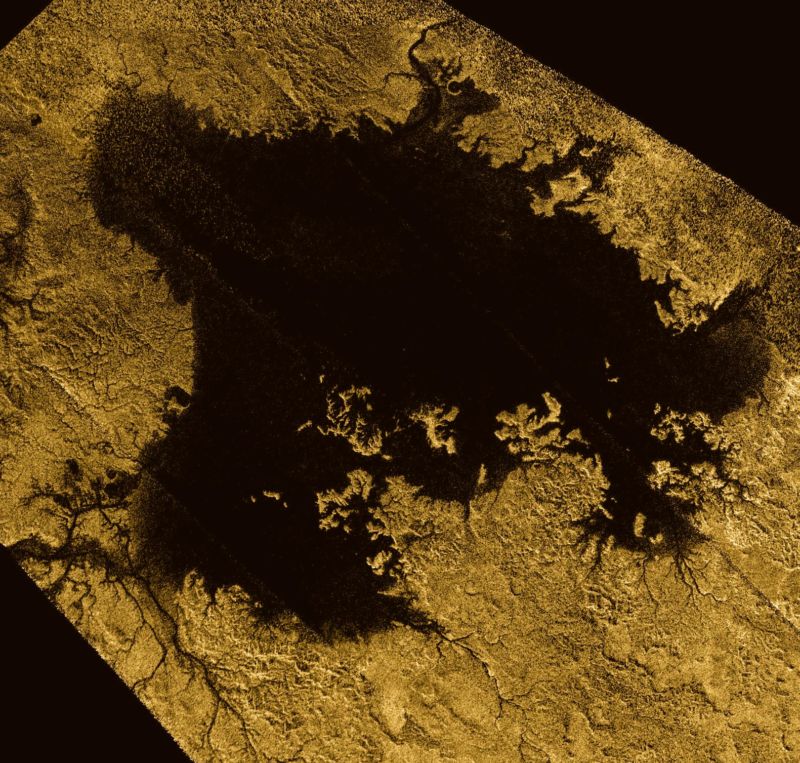

Enlarge / Ligeia Mare, the second-largest body of liquid hydrocarbons on Titan.

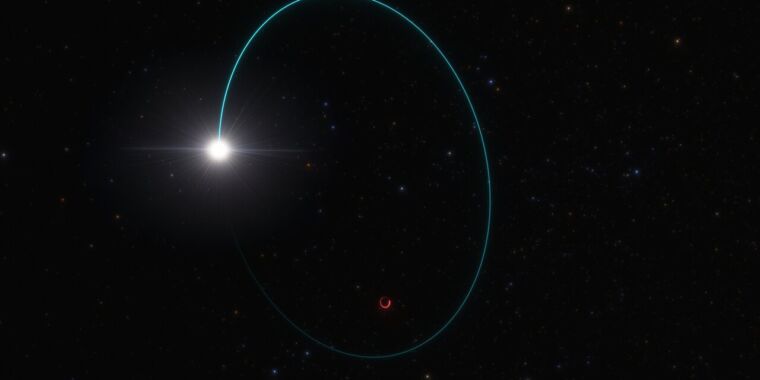

During its T85 Titan flyby on July 24, 2012, the Cassini spacecraft registered an unexpectedly bright reflection on the surface of the lake Kivu Lacus. Its Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) data was interpreted as a roughness on the methane-ethane lake, which could have been a sign of mudflats, surfacing bubbles, or waves.

“Our landscape evolution models show that the shorelines on Titan are most consistent with Earth lakes that have been eroded by waves,” says Rose Palermo, a coastal geomorphologist at St. Petersburg Coastal and Marine Science Center, who led the study investigating signatures of wave erosion on Titan. The evidence of waves is still inconclusive, but future crewed missions to Titan should probably pack some surfboards just in case.

Troubled seas

While waves have been considered the most plausible explanation for reflections visible in Cassini’s VIMS imagery for quite some time, other studies aimed to confirm their presence found no wave activity at all. “Other observations show that the liquid surfaces have been very still in the past, very flat,” Palermo says. “A possible explanation for this is at the time we were observing Titan, the winds were pretty low, so there weren’t many waves at that time. To confirm waves, we would need to have better resolution data,” she adds.

The problem is that this higher-resolution data isn’t coming our way anytime soon. Dragonfly, the next mission to Titan, isn’t supposed to arrive until 2034, even if everything goes as planned.

To get a better idea about possible waves on Titan a bit sooner, Palermo’s team went for inferring their presence from indirect cues. The researchers assumed shorelines on Titan could have been shaped by one of three candidate scenarios. They first assumed there was no erosion at all; the second modeled uniform erosion caused by the dissolution of the bedrock by the ethane-methane liquid; and the third assumed erosion by wave activity. “We took a random topography with rivers, filled up the basin-flooding river valleys all around the lake. Then, we then used landscape evolution computer model to erode the coast to 50 percent of its original size,” Palermo explains.

Sizing the waves

Palermo’s simulations showed that wave erosion resulted in coastline shapes closely matching those actually observed on Titan.

The team validated its model using data from closer to home. “We compared using the same statistical analysis to lakes on Earth, where we know what the erosion processes are. With certainty greater than 77.5 percent, we were able to predict those known processes with our modeling,” Palermo says.

But even the study that claimed there were waves visible in the Cassini’s VIMS imagery concluded they were roughly 2 centimeters high at best. So even if there are waves on Titan, the question is how high and strong are they?

According to Palermo, wave-generation mechanisms on Titan should work just like they do on Earth, with some notable differences. “There is a difference in viscosity between water on Earth and methane-ethane liquid on Titan compared to the atmosphere,” says Palermo. The gravity is also a lot weaker, standing at only one-seventh of the gravity on Earth. “The gravity, along with the differences in material properties, contributes to the waves being taller and steeper than those on Earth for the same wind speed,” says Palermo.

But even with those boosts to size and strength, could waves on Titan actually be any good for surfing?

Surf’s up

“There are definitely a lot of open questions our work leads to. What is the direction of the dominant waves? Knowing that can tell us about the winds and, therefore, about the climate on Titan. How large do the waves get? In the future, maybe we could tell that with modeling how much erosion occurs in one part of the lake versus another in estimated timescales. There is a lot more we could learn,” Palermo says. As far as surfing is concerned, she said that, assuming a minimum height for a surfable wave of around 15 centimeters, surfing on Titan should most likely be doable.

The key limit on the size and strength of any waves on Titan is that most of its seas are roughly the size of the Great Lakes in the US. The largest of them, the Kraken Mare, is roughly as large as the Caspian Sea on Earth. There is no such thing as a global ocean on Titan, and this means the fetch, the distance over which the wind can blow and grow the waves, is limited to tens of kilometers instead of over 1,500 kilometers on Earth. “Still, some models show that the waves on Titan be as high as one meter. I’d say that’s a surfable wave,” Palermo concluded.

Saturn’s moon Titan has shorelines that appear to be shaped by waves Read More »