These 60,000-year-old poison arrows are oldest yet found

Poisoned arrows or darts have long been used by cultures all over the world for hunting or warfare. For example, there are recipes for poisoning projective weapons, and deploying them in battle, in Greek and Roman historical documents, as well as references in Greek mythology and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Chinese warriors over the ages did the same, as did the Gauls and Scythians, and some Native American populations.

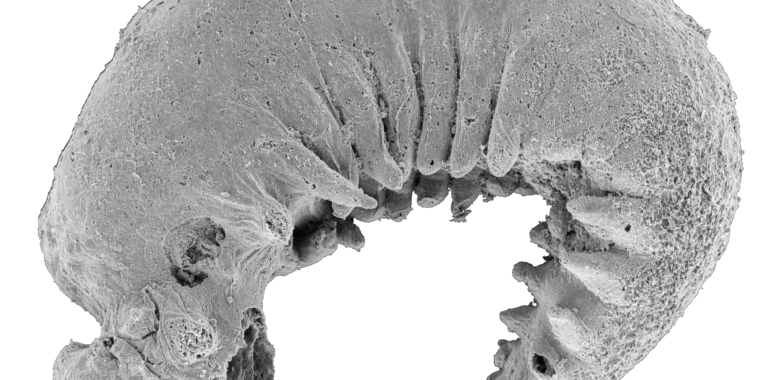

Archaeologists have now found traces of a plant-based poison on several 60,000-year-old quartz Stone Age arrowheads found in South Africa, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances. That would make this the oldest direct evidence of using poisons on projectiles—a cognitively complex hunting strategy—and pushes the timeline for using poison arrows back into the Pleistocene.

The poisons commonly used could be derived from plants or animals (frogs, beetles, venomous lizards). Plant-based examples include curare, a muscle relaxant that paralyzes the victim’s respiratory system, causing death by asphyxiation. Oleander, milkweeds, or inee (onaye) contain cardiac glucosides. In Southeast Asia, the sap or juice of seeds from the ancar tree is smeared on arrowheads, which causes paralysis, convulsions, and cardiac arrest due to the presence of toxins like strychnine. Several species of aconite are known for their use as arrow poisons in Siberia and northern Japan.

According to the authors, up until now, the earliest direct evidence of poisoned arrows dates back to the mid-Holocene. For instance, scientists found traces of toxic glycoside residues on 4,000-year-old bone-tipped arrows recovered from an Egyptian tomb, as well as on bone arrow points from 6,700 years ago excavated from South Africa’s Kruger Cave. The only prior evidence of using poisons for hunting during the Pleistocene is a “poison applicator” found at Border Cave in South Africa, along with a lump of beeswax.

Milk of the poisonous onion

The authors sampled 10 quartz-backed arrowheads recovered from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter site in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The results revealed that five of the 10 tested tips had traces of compounds found in Boophone disticha, aka gifbol (poisonous onion), sometimes called the century plant, which is common throughout South Africa. Various parts of the plant have been used as an analgesic (specifically a volatile oil called eugenol) as well as for poisonous hunting purposes. Its more toxic compounds include buphandrine, crinamidine, and buphanine; the latter is similar in effect to scopolamine and can cause hallucinations, coma, or death.

These 60,000-year-old poison arrows are oldest yet found Read More »