China has a big problem with super gonorrhea, study finds

Alarming —

Drug-resistant gonorrhea is a growing problem—one that doesn’t heed borders.

Enlarge / A billboard from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation is seen on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, California, on May 29, 2018, warning of a drug-resistant gonorrhea.

Health officials have long warned that gonorrhea is becoming more and more resistant to all the antibiotic drugs we have to fight it. Last year, the US reached a grim landmark: For the first time, two unrelated people in Massachusetts were found to have gonorrhea infections with complete or reduced susceptibility to every drug in our arsenal, including the frontline drug ceftriaxone. Luckily, they were still able to be cured with high-dose injections of ceftriaxone. But, as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention bluntly notes: “Little now stands between us and untreatable gonorrhea.”

If public health alarm bells could somehow hit a higher pitch, a study published Thursday from researchers in China would certainly accomplish it. The study surveyed gonorrhea bacterial isolates—Neisseria gonorrhoeae—from around the country and found that the prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistant isolates nearly tripled between 2017 and 2021. Ceftriaxone-resistant strains made up roughly 8 percent of the nearly 3,000 bacterial isolates collected from gonorrhea infections in 2022. That’s up from just under 3 percent in 2017. The study appears in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

While those single-digit percentages may seem low, compared to other countries they’re extremely high. In the US, for instance, the prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistant strains never went above 0.2 percent between 2017 and 2021, according to the CDC. In Canada, ceftriaxone-resistance was stable at 0.6 percent between 2017 and 2021. The United Kingdom had a prevalence of 0.21 percent in 2022.

Ceftriaxone is currently the first-line treatment for gonorrhea because Neisseria gonorrhoeae has spent the past several decades building up resistance to pretty much everything else. As the CDC notes, in the 1980s, the drugs of choice for gonorrhea infections were penicillin and tetracycline. But the bacteria developed resistance. By the 1990s, the CDC was forced to switch to a class of antibiotics called fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin (Cipro). But fluoroquinolone-resistance developed, too, and resistance to Cipro is now widespread. In the early 2000s, the CDC began having to tweak the recommendations as resistance spread to new places and populations.

Resistance rising

By 2007, the agency switched to cephalosporins, including cefixime. In 2010, the CDC updated the treatment again, recommending that doctors combine cephalosporins with one of two other types of antibiotics—azithromycin or doxycycline—to try to thwart the development of resistance. But, it also was no use. Two years later, in 2012, the CDC updated recommendations when cefixime resistance developed. In 2020, azithromycin was also abandoned. The cephalosporin ceftriaxone is the last drug standing in the US to treat gonorrhea infections.

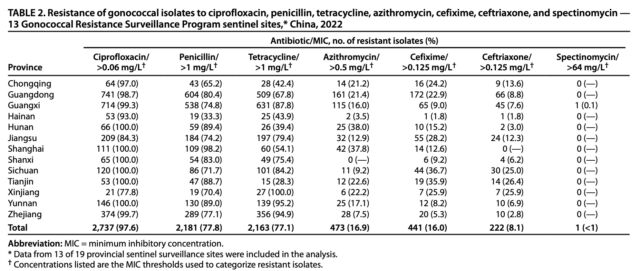

Enlarge / Resistance of gonococcal isolates to ciprofloxacin, penicillin, tetracycline, azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone, and spectinomycin—13 Gonococcal Resistance Surveillance Program sentinel sites, China, 2022.

In China, the swift spread of ceftriaxone-resistance isolates is alarming. The data stems from 2,804 isolates, representing 2.9 percent of all cases reported in China during 2022. Those figures come from 13 of the country’s 19 provinces. While the overall prevalence of ceftriaxone-resistance isolates was 8.1 percent among the 2,804 isolates, five of those 13 provinces had prevalence rates above 10 percent. Three provinces had prevalence rates above 25 percent. In all, 18 isolates were resistant to all the antibiotics tested except for a bygone antibiotic called spectinomycin, which is discontinued in the US and elsewhere.

The study has limitations. For one, the reported number of gonorrhea cases are very likely an undercount of actual cases. Beyond gaps in reporting, many people with gonorrhea have no symptoms and, as such, don’t seek treatment. Additionally, the isolates the researchers did have represented less than 3 percent of reported cases, so it’s possible the prevalence rates don’t represent the isolates of the entire country. Also, the researchers didn’t have detailed case data that might help identify specific risk factors for resistance development, such as the antibiotic treatments patients had. The authors did note that antibiotics are only given by prescription in China.

“These findings underscore the urgent need for a comprehensive approach to address antibiotic-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in China, including identifying factors contributing to this high resistance rate, especially in provinces where the percentage of gonococcal isolates resistant to ceftriaxone is >10 percent,” the authors write.

But they also note that this is not just an alarming finding for China but also a “pressing public health concern” for the entire world. “These resistant clones have spread internationally, and collaborative cross-border efforts will be essential to monitoring and mitigating its further spread,” they write.

China has a big problem with super gonorrhea, study finds Read More »