First revealed in spy photos, a Bronze Age city emerges from the steppe

An unexpectedly large city lies in a sea of grass inhabited largely by nomads.

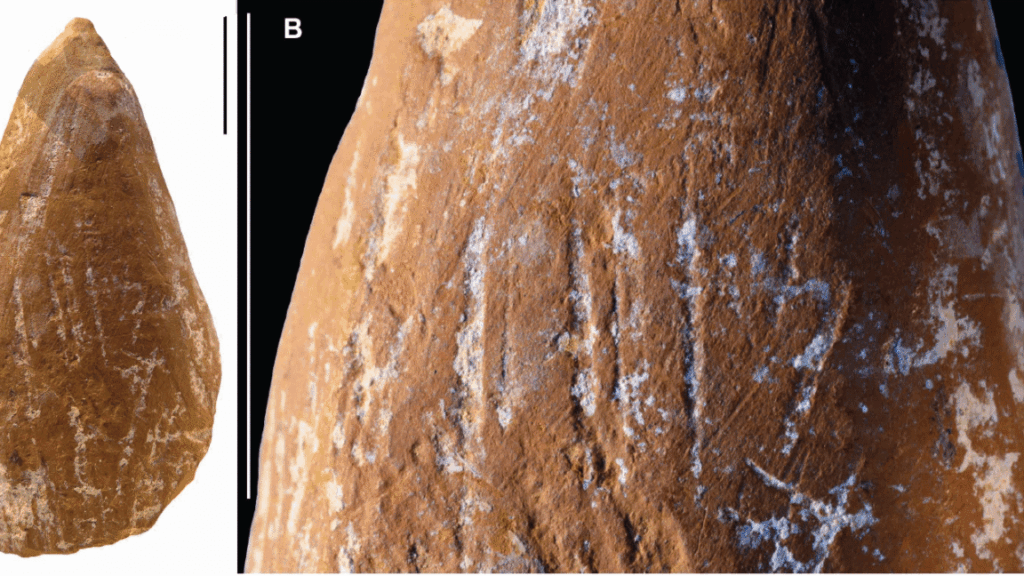

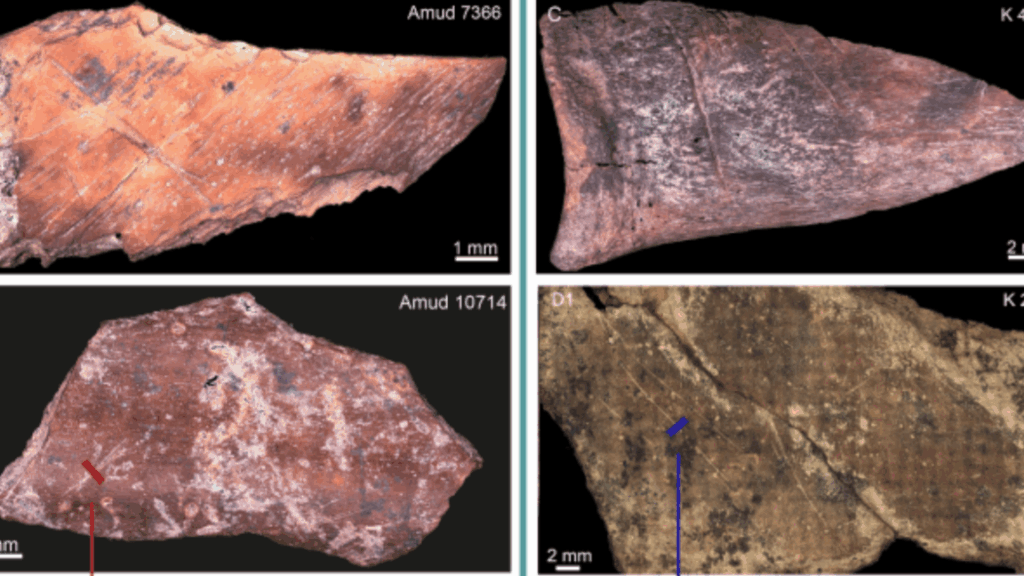

This bronze ax head was found in the western half of Semiyarka. Credit: Radivojevic et al. 2025

Today all that’s left of the ancient city of Semiyarka are a few low earthen mounds and some scattered artifacts, nearly hidden beneath the waving grasses of the Kazakh Steppe, a vast swath of grassland that stretches across northern Kazakhstan and into Russia. But recent surveys and excavations reveal that 3,500 years ago, this empty plain was a bustling city with a thriving metalworking industry, where nomadic herders and traders might have mingled with settled metalworkers and merchants.

Radivojevic and Lawrence stand on the site of Semiyarka. Credit: Peter J. Brown

Welcome to the City of Seven Ravines

University College of London archaeologist Miljana Radivojevic and her colleagues recently mapped the site with drones and geophysical surveys (like ground-penetrating radar, for example), tracing the layout of a 140-hectare city on the steppe in what’s now Kazakhstan.

The Bronze Age city once boasted rows of houses built on earthworks, a large central building, and a neighborhood of workshops where artisans smelted and cast bronze. From its windswept promontory, it held a commanding view of a narrow point in the Irtysh River valley, a strategic location that may have offered the city “control over movement along the river and valley bottom,” according to Radivojevic and her colleagues. That view inspired archaeologists’ name for the city: Semiyarka, or City of Seven Ravines.

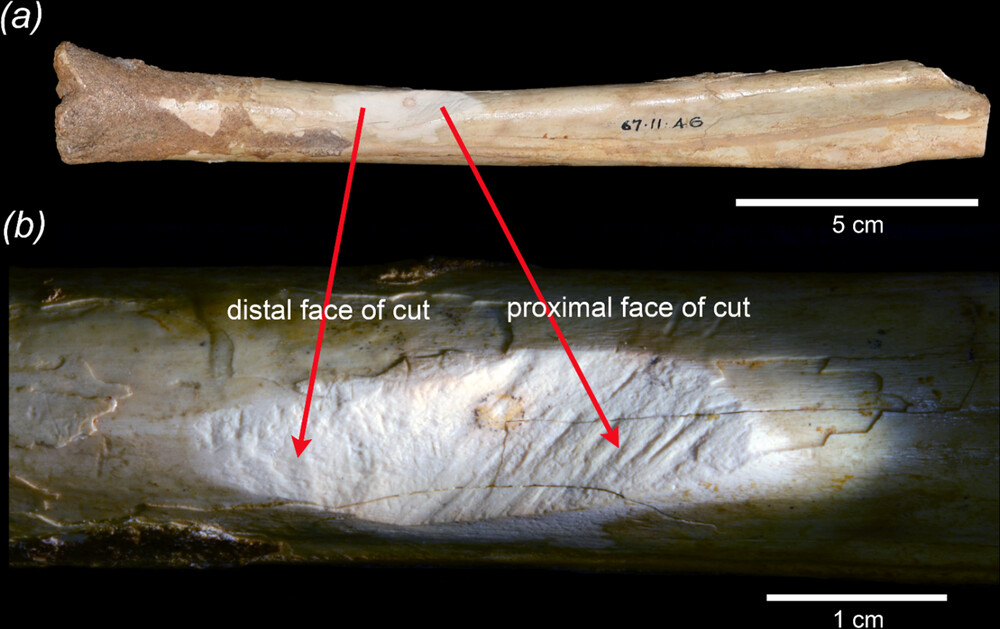

Archaeologists have known about the site since the early 2000s, when the US Department of Defense declassified a set of photographs taken by its Corona spy satellite in 1972, when Kazakhstan was a part of the Soviet Union and the US was eager to see what was happening behind the Iron Curtain. Those photos captured the outlines of Semiyarka’s kilometer-long earthworks, but the recent surveys reveal that the Bronze Age city was much larger and much more interesting than anyone realized.

This 1972 Corona image shows the outlines of Semiyarka’s foundations. Radivojevic et al. 2025

When in doubt, it’s potentially monumental

Most people on the sparsely populated steppe 3,500 years ago stayed on the move, following trade routes or herds of livestock and living in temporary camps or small seasonal villages. If you were a time-traveler looking for ancient cities, the steppe just isn’t where you’d go, and that’s what makes Semiyarka so surprising.

A few groups of people, like the Alekseeva-Sargary, were just beginning to embrace the idea of permanent homes (and their signature style of pottery lies in fragments all over what’s left of Semiyarka). The largest ancient settlements on the steppe covered around 30 hectares—nowhere near the scale of Semiyarka. And Radivojevic and her colleagues say that the layout of the buildings at Semiyarka “is unusual… deviating from more conventional settlement patterns observed in the region.”

What’s left of the city consists mostly of two rows of earthworks: kilometer-long rectangles of earth, piled a meter high. The geophysical survey revealed that “substantial walls, likely of mud-brick, were built along the inside edges of the earthworks, with internal divisions also visible.” In other words, the long mounds of earth were the foundations of rows of buildings with rooms. Based on the artifacts unearthed there, Radivojevic and her colleagues say most of those buildings were probably homes.

The two long earthworks meet at a corner, and just behind that intersection sits a larger mound, about twice the size of any of the individual homes. Based on the faint lines traced by aerial photos and the geophysical survey, it may have had a central courtyard or chamber. In true archaeologist fashion, Durham University archaeologist Dan Lawrence, a coauthor of the recent paper, describes the structure as “potentially monumental,” which means it may have been a space for rituals or community gatherings, or maybe the home of a powerful family.

The city’s layout suggests “a degree of architectural planning,” as Radivojevic and her colleagues put it in their recent paper. The site also yielded evidence of trading with nomadic cultures, as well as bronze production on an industrial scale. Both are things that suggest planning and organization.

“Bronze Age communities here were developing sophisticated, planned settlements similar to those of their contemporaries in more traditionally ‘urban’ parts of the ancient world,” said Lawrence.

Who put the bronze in the Bronze Age? Semiyarka, apparently

Southeast of the mounds, the ground was scattered with broken crucibles, bits of copper and tin ore, and slag (the stuff that’s left over when metal is extracted from ore). That suggested that a lot of smelting and bronze-casting happened in this part of the city. Based on the size of the city and the area apparently set aside for metalworking, Semiyarka boasted what Radivojevic and her colleagues call “a highly-organized, possibly limited or controlled, industry of this sought-after alloy.”

Bronze was part of everyday life for people on the ancient steppes, making up everything from ax heads to jewelry. There’s a reason the period from 2000 BCE to 500 BCE (mileage may vary depending on location) is called the Bronze Age, after all. But the archaeological record has offered almost no evidence of where all those bronze doodads found on the Eurasian steppe were made or who was doing the work of mining, smelting, and casting. That makes Semiyarka a rare and important glimpse into how the Bronze Age was, literally, made.

Radivojevic and her colleagues expected to find traces of earthworks or the buried foundations of mud-brick walls, similar to the earthworks in the northwest, marking the site of a big, centralized bronze-smithing workshop. But the geophysical surveys found no walls at all in the southeastern part of the city.

“This area revealed few features,” they wrote in their recent paper (archaeologists refer to buildings and walls as features), “suggesting that metallurgical production may have been dispersed or occurred in less architecturally formalized spaces.” In other words, the bronzesmiths of ancient Semiyarka seem to have worked in the open air, or in a scattering of smaller, less permanent buildings that didn’t leave a trace behind. But they all seem to have done their work in the same area of the city.

Connections between nomads and city-dwellers

East of the earthworks lies a wide area with no trace of walls or foundations beneath the ground, but with a scattering of ancient artifacts lying half-buried in the grass. The long-forgotten objects may mark the sites of “more ephemeral, perhaps seasonal, occupation,” Radivojevic and her colleagues suggested in their recent paper.

That area makes up a large chunk of the city’s estimated 140 hectares, raising questions about how many people lived here permanently, how many stopped here along trade routes or pastoral migrations, and what their relationship was like.

A few broken potsherds offer evidence that the settled city-dwellers of Semiyarka traded regularly with their more mobile neighbors on the steppe.

Within the city, most of the ceramics match the style of the Alekseevka-Sargary people. But a few of the potsherds unearthed in Semiyarka are clearly the handiwork of nomadic Cherkaskul potters, who lived on this same wide sea of grass from around 1600 BCE to 1250 BCE. It makes sense that they would have traded with the people in the city.

Along the nearby Irtysh River, archaeologists have found faint traces of several small encampments, dating to around the same time as Semiyarka’s heyday, and two burial mounds stand north of the city. Archaeologists will have to dig deeper, literally and figuratively, to piece together how Semiyarka fit into the ancient landscape.

The city has stories to tell, not just about itself but about the whole vast, open steppe and its people.

Antiquity, 2025. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.10244 (About DOIs).

First revealed in spy photos, a Bronze Age city emerges from the steppe Read More »