Some points of order before we begin the monthly:

-

It’s inauguration day, so perhaps hilarity is about to ensue. I will do my best to ignore most forms of such hilarity, as per usual. We shall see.

-

My intention is to move to a 5-posts-per-week schedule, with more shorter posts in the 2k-5k word range that highlight particular subtopic areas or particular events that would have gone into broader roundups.

-

This means that the Monthly Roundups will likely be shorter.

-

If you’re considering reading Agnes Callard’s new book, Open Socrates, I am reading it now and can report it is likely to get the On the Edge treatment and its own week, but of course it is too soon to know.

-

I may be doing some streams of myself working, via Twitch, primarily so that a volunteer can look for ways to build me useful tools or inform me of ways to improve my workflow. You are also of course welcome to watch, either live or the recordings, to see how the process works, but I make zero promises of any form of interaction with the audience here. I also might stream Slay the Spire 2 when the time comes, once I have access and they permit this.

On with the show.

-

Bad News.

-

Wanna Bet.

-

A Matter of Trust.

-

Against Against Nuance.

-

Government Working.

-

Scott Alexander on Priesthoods.

-

NYC Congestion Pricing Bonus Coverage.

-

Positive Sum Thinking.

-

Antisocial Media.

-

The Price of Freedom.

-

Mood Music.

-

Dedebanking.

-

Good News, Everyone.

-

While I Cannot Condone This.

-

Clear Signal.

-

When People Tell You Who They Are Believe Them.

-

What Doesn’t Go Without Saying.

-

Party at My Place.

-

I Was Promised Flying Self-Driving Cars.

-

Gamers Gonna Game Game Game Game Game.

-

For Your Entertainment.

-

Sports Go Sports.

-

The Lighter Side.

PornHub cuts off Florida, the 13th state to lose access, after Florida passed an age verification law, and PornHub quite reasonably does not want to ask for your ID.

Running for Congress is a horrible deal and essentially no sane person would do it. If we want good people to run for Congress and for them not to consider sleeping on cots in their office we need to dramatically raise pay, which we should do.

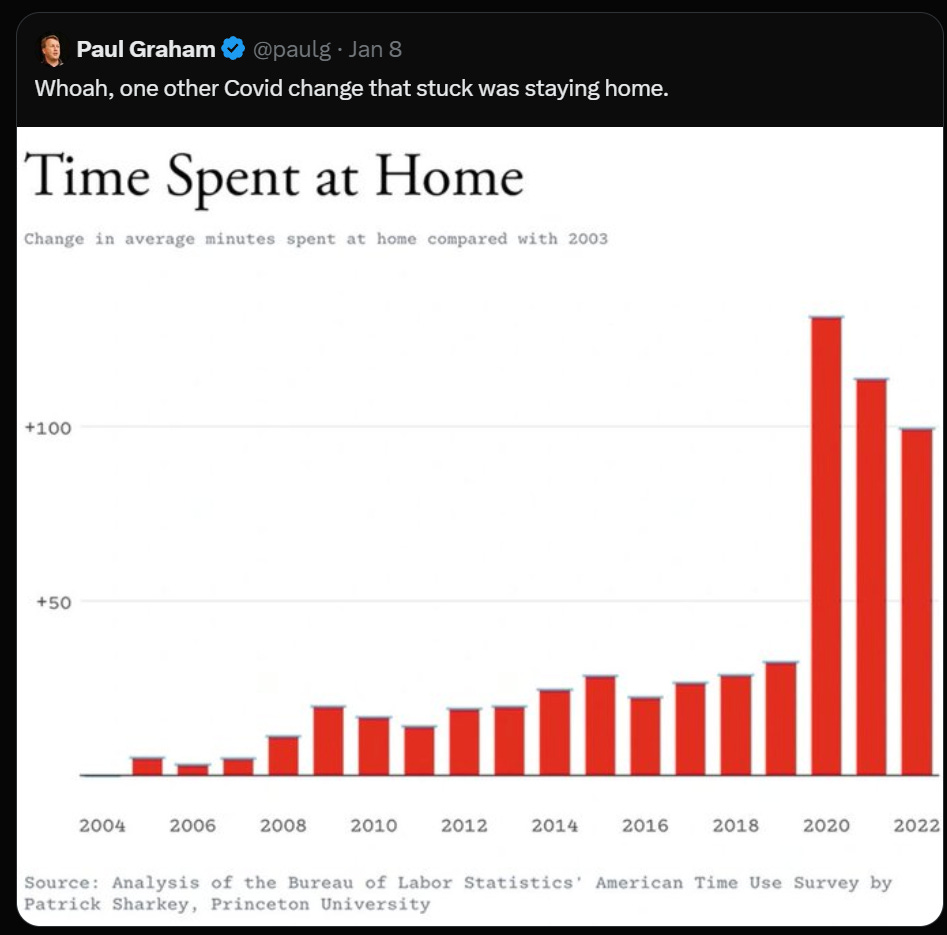

Share of American adults having dinner or drinks with friends on any given night has declined by more than 30% in the past 20 years, and changes from Covid mostly have not reversed.

Older software engineers often report that once they lose their current job, they can’t get new jobs and that this is because of rampant agism, others report this is not true, and it’s you in particular that sucks, or you’re seeing selection effects because most of the good ones get forced into management or start their own companies. It’s certainly not universal, but my sense is that many underestimate the downside risk of this outcome.

The replication crisis comes for experimental asset market results, out of 17 attempted replications only 3 results were significant with average effect size 2.9% of the original estimates.

Gary Marcus places another highly virtuous public bet, this time with Derya Unutmaz.

Derya Unutmaz, M.D.: I accept this, and in fact, I counteroffer a $10,000 bet that by 2045 we will surpass a life expectancy of 95, with an increase of more than a year each year thereafter. I intend to collect it, so don’t die!

Gary Marcus: I hereby accept

@deryaTR_’s $10,000 bet on human life expectancy 20 years hence.

Winnings go to charity, and I hope desperately that I lose!

The bet is resolved once 2045 data are available. (I will not hold him to the “thereafter” part. But I hope he is correct on that part, too.)

Best part of this bet is everyone is rooting for Derya. This is largely but not entirely a bet on AI capabilities. If we get an intelligence explosion relatively soon, then either life expectancy will go way down but Gary won’t be around to collect, or if things go well I do expect to be able to get life expectancy rising rapidly. If AI stalls out, then it gets a lot harder for Derya to win, but it isn’t impossible.

There’s always the rub of whether, when you lose, you actually pay…

Sam Harris accuses Elon Musk of having bet him a $1 million in charitable donation at 1000:1 odds (against a $1k bottle of tequila) that there would not be 35k Covid cases in America, and then refusing to pay and turning against him when Harris tried to collect. Both halves are rather terrible if true, and it is a strange accusation to make if it is false.

There are also rather well-supported accusations that Elon Musk’s supposed Path of Exile 2 characters are, at best, being played primarily by someone else. He doesn’t seem to even understand many basics of how the game works, and the amount of time obviously required to get the characters in question is obviously impossible given his time constraints. Honestly this was pretty embarrassing, and it tells you a lot about a person if they decide to do this, including the fact that it was 100% to be caught.

Does Musk pull off some impressive feats of gaming? It seems like he does.

Grimes: Just for my personal pride, I would like to state that the father of my children was the first american druid in diablo to clear abattoir of zir and ended that season as best in the USA. He was also ranking in Polytopia, and beat Felix himself at the game. I did observe these things with my own eyes. There are other witnesses who can verify this. That is all.

However, when you pull a stunt like this, you call all that into question, and you dishonor the game, all of gaming and also yourself.

On some level, one must wonder if this was intentional.

Tyler Cowen challenges whether there can be ‘an intermediate position on immigration.’ This is another form of Dial Theory, where one says that all one can say is Yay [X] or Boo [X], so saying something nuanced only matters insofar as it says Yay or Boo. That what matters is the vibe, not the content.

Tyler Cowen: Increasingly, I have the fear that “general sympathies toward foreigners” is doing much of the load of the work here. This is one reason, but not the only one, why I am uncomfortable with a lot of the rhetoric against less skilled immigrants. It may also be the path toward a tougher immigration policy more generally.

I hope I am wrong about this. Right now the stakes are very high.

I have never written the post Against Dial Arguments, or perhaps Against Against Nuance. Or perhaps Stop Prioritizing the Vibes? This seems like a clear example. Tyler has had several posts on related issues, where he frames discussions as purely being on the basis of what would be convincing to the public in the immediate term, rather than any attempt to actually use asymmetric weapons or argue for actually optimal understanding or policy.

I also am much less cynical here. I believe that this distinction (between legal or skill immigration, versus illegal or unskilled) not only can be drawn, but that drawing it is the way to win hearts and minds on the issue.

So much of how I disagree with Tyler Cowen in general is perhaps embodied by his response to the death of Jimmy Carter. Essentially Tyler said that Carter had great accomplishments that stand the test of time, but the vibes were off, so he much preferred Ford, Clinton or Reagan – and without a ‘I know this is foolish of me but’ attached to that statement.

If Carter killed it on foreign policy and peace, and killed it on being moral and standing up for what is right, and killed it on monetary policy and deregulation as a Democrat when we desperately needed both, and you realize this, then I don’t care if the vibes are off. That’s amazing. You better recognize.

I pledge not to ever vote for anyone who claimed in public that the ERA was a legal part of our constitution. This is a dealbreaker, full stop. Please remind me, if this ever becomes relevant. Note that this includes one of my senators, Gillibrand, and also Duckworth. A similar reaction goes for organizations that bought into this, which they claim includes the American Bar Association.

I also note I don’t understand why the Archivist of the United States matters here. Kudos to her for pointing out that A is A, the bar sure is low these days, but her role is ceremonial. If she declared that somehow it had been ratified, wouldn’t SCOTUS simply inform everyone that it wasn’t? How is this not ultimately their call?

DOGE picks a fight over the Christmas tree funding package, and loses hard. It’s not only that they didn’t get most of what they wanted. It’s that they picked the wrong fight on multiple levels, targeting the traditional superficially flashy ‘wasteful spending’ instead of places that matter, in a spot where they needed congressional approval. They need to wise up, fast.

Our government will sometimes take your child away for months or longer because of a positive drug test reported by a hospital… for the same drugs that hospital gave you. And there are several cases where, after the authorities in question were made aware of what happened, Child Services not only did not profusely apologize, they didn’t let the matter drop.

His post is rather scathing. The fact that it tries not to be only makes it worse.

Let’s start out with a quote for those who thought I was kidding when I said modern architecture was a literal socialist plot to make our lives worse:

Peter Eisenman: What I’m suggesting is that if we make people so comfortable in these nice little structures of yours, that we might lull them into thinking that everything’s all right, Jack, which it isn’t. And so the role of art or architecture might be just to remind people that everything wasn’t all right.

I say the proper role of architecture is to make things as all right and good as possible.

Are the other similar academic determiners of truth and worth any better?

Let’s consider economics.

Scott Alexander: I used to wonder why so many econ-bloggers I liked were at GMU. GMU only is only the 74th best economics department in the country, but more than half of the econbloggers I like are affiliated with it in some way (Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok, Garett Jones, Robin Hanson, Bryan Caplan, Arnold Kling, Scott Sumner, Mark Koyama, sorry if I’m forgetting anyone!).

…

When I asked academics about this, they didn’t find it mysterious at all. The average high-ranked economics department doesn’t care that you have a popular blog. They might even count it against you. Only your reputation within the priesthood matters.

This is my experience too.

What’s weird is that Tyler Cowen is responsible for the majority of the time I encounter in practice the pure form of the argument that ‘blogs don’t count, only properly peer reviewed and published papers do, so your argument is invalid. I am not only allowed to but almost obligated to ignore it until you change that. Good luck.’

Whereas this exact principle is used to exclude essentially all the economists I respect most from the core economic discourse – and most of them are listed above, in one place, at ‘the 74th best economics department in the country.’

I have no problem with various people playing intricate ingroup status games. But when that makes my buildings ugly and economics largely Obvious Nonsense, and so on throughout the various disciplines with notably rare exceptions, and those with power are accepting their status claims, and they’re doing it all effectively at public expense, I’m not a fan.

Scott Alexander tries to say that hard boundaries with the public are not only useful, but even necessary.

Scott Alexander: This hard boundary – this contempt for two-way traffic with the public – might seem harsh to outsiders. But it’s an adaptive artifact produced by cultural evolution as it tries to breed priesthoods that can perform their epistemic function.

The outside world is so much bigger than the priesthoods, so much richer, so full of delicious deposits of status waiting to be consumed – that any weaker border would soon be overrun, with all priesthood members trying to garner status with the public directly.

Only the priesthoods that inculcated the most powerful contempt for the public survived to have good discussions and output trustworthy recommendations.

Yeah, no. Of course you need to ignore the public when it’s espousing Obvious Nonsense and Did Not Do the Research. But if and when the public has good ideas, that is great. Those saying otherwise are rent seekers whose conversations are engaged in a conspiracy against the public, or some contrivance to raise prices.

Several other sections are so unconvincing as to sound absurd. Yes, there is messiness in not doing everything according to only the sacred laws of communication and trade, but come on with these excuses.

Then there’s the point that so many of these organizations got politically captured. Scott Alexander offers a theory as to how that happened. It isn’t flattering.

Another example of that this month was the American Economic Association once again makes clear it is fully partisan and unafraid to stick its nose where it does not belong, as it encouraged members to move from Twitter to BlueSky.

It also seems suspect, but it seems to be pointing towards some part of the story.

Scott Alexander: I think the priesthoods are still good at their core functions. Doctors are good at figuring out which medicines work. Journalists are good at learning which Middle Eastern countries are having wars today and interviewing the participants about what fighting wars in the Middle East is like. Architects are good at designing buildings that don’t collapse.

But now this truth must coexist with an opposite truth: the priesthoods are no longer trustworthy on anything adjacent to politics.

This is the standard, which is rather grim and… well, it’s close.

Yes, I can probably count on architects to design builds that don’t collapse. That’s a case where they are forced to match physical reality. We’d find out real quick if they stopped doing that one. But I can’t count on them to, beyond this basic requirement, design good buildings I want to exist.

I am not convinced I can count on journalists to tell me which Middle Eastern countries are having wars today. There has often been quite a lot of them pretending that countries that are effectively fighting wars (e.g. through proxies) are not fighting wars today. If I want to know who is and is not fighting wars today, my best way of doing that is not to trust journalists too much on that question.

Doctors are not good at figuring out what medicines work. I know this because I had a company based largely on trying to figure out which medicines work in a given context, and because I know doctors and I know people who encounter doctors. Doctors are much better than random, or a random member of the public, at this, to be sure. Mostly they learn a set of heuristics, which they apply, and that’s not too bad in most situations and for many practical purposes you can largely trust them, but don’t kid yourself.

Maybe we should accept this. Maybe we should say: to hell with the priesthoods!

I think this would be a mistake.

My thesis in this essay is that the priesthoods are neither a rent-seeking clique nor an epiphenomenon of the distribution of knowledgeable people.

In what universe are these not rent-seeking cliques?

They are not only rent-seeking cliques. The stationary bandits have to provide some value to defend their turf, after all. But to use doctors as a main example and pretend they are not very literally a rent-seeking clique – whatever else they also are – is rather deeply confusing.

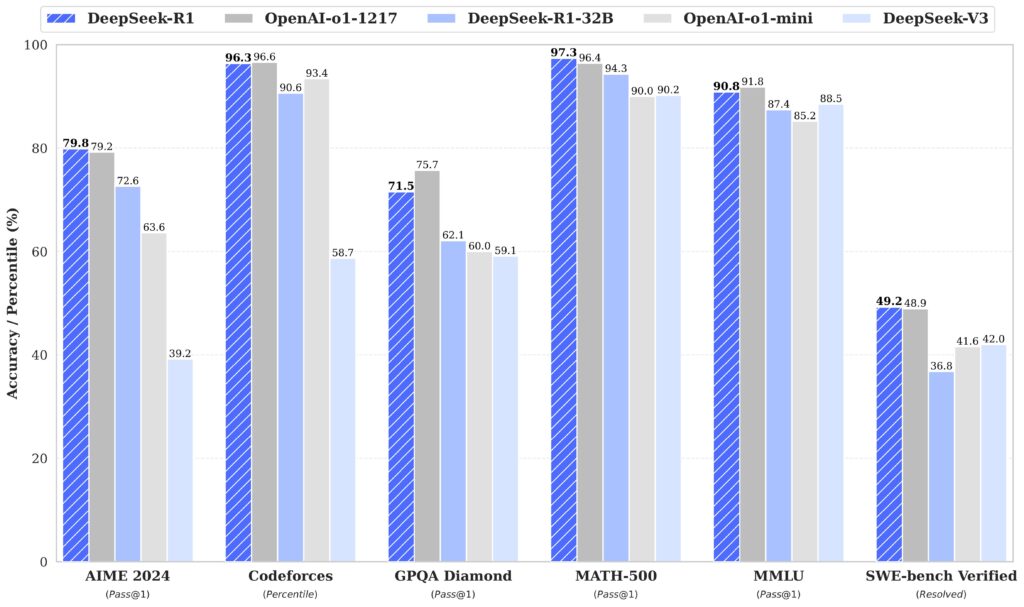

Scott Alexander complains that the priesthoods are captured by left-wing politics and often rather brazenly doing politics, which I agree is an important issue here, then he posts this chart.

But then he says something weird.

The meme is supposed to be a criticism of the priesthoods. But I genuinely miss the step where you had to find a priest who made something up, rather than making it up yourself directly.

Priesthoods make things up differently from normal people. Even when they’re corrupt, they still have a reputation to maintain. I’ve written about this before at Bounded Distrust and The Media Very Rarely Lies.

I mostly disagree. If you’re going to play the ‘I made it up’ game, make it up. I get the advantage of the making things up having some amount of restraint on it. That can be helpful on occasion.

At this point, the ‘jealously guard their own reputation’ function is ineffective enough as a group that I don’t see the point. Individuals also guard their own reputations, often far better, whereas the priesthoods have burned their reputations down. They’ve both collectively decided that they are going to effectively assert that which is not as a group plan in many cases, politically and otherwise, and also members are increasingly happy to go rogue.

So priesthoods’ standards fall slowly; a substantial fraction of doctors need to have been corrupted before any doctor feels comfortable acting in a corrupt way.

The part where individual doctors adjust slowly is a feature. But our perceptions shifting similarly slowly is a rather serious bug.

You know what priesthood Scott Alexander doesn’t discuss? Actual priests.

In particular, he doesn’t discuss Rabbis. In my culture, the priesthood argues with each other and with you, endlessly, about everything. The public is not only allowed but encouraged to participate in this. And if you want to be a Rabbi, mostly you don’t need some official central authority’s permission, or to adhere to their rules. There’s a bunch of training and all that, but ultimately you need the congregation to decide that you’re their Rabbi. That’s it.

He also doesn’t go back and revisit the original question he starts with, of the Rationalist priesthood, in the Rationalist community. Do we exclude ‘the public’? Yes, in the sense that if the average person tried to participate, we’d downvote and ignore them. But we’d do so not because they didn’t have credentials. We’d do it because we don’t respect your arguments and way of thinking. We’d notice you do not know The Way, and treat you accordingly until that changes. But that’s the whole point.

You can just do things. Except the priesthoods mostly are indeed rent-seeking cliques, and have sought legal protections against you just doing things, so you can’t. And in other cases, they’re conspiring to make it not respectable, and invalid, to do things without joining the clique. Then instructing everyone in the clique not to do things.

Which reliably renders those areas dead or stagnant, at best. Don’t let them do it.

(See here for my main coverage, from the 14th.)

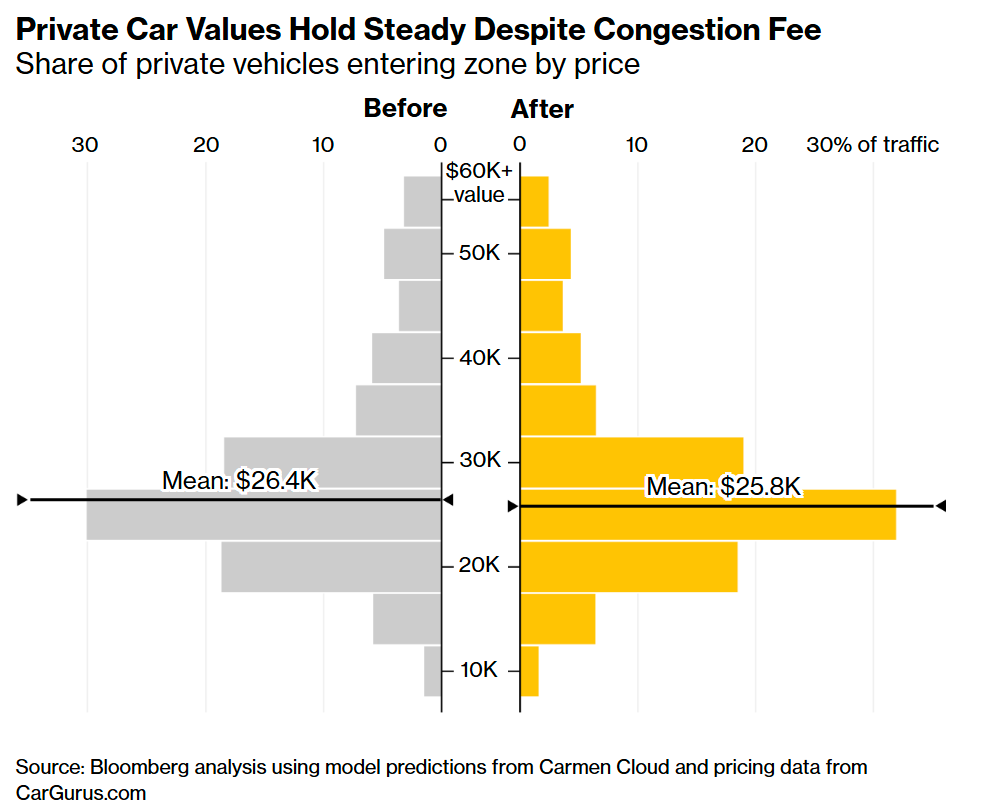

Bloomberg finds (in line with MTA data and also claimed expectations) that the number of cars entering the congestion zone is down 8%. That puts an upper bound on the negative impacts from people not coming in. The share of taxis is up about 6%, replacing private cars.

An estimate of average vehicle values shows that there has not been a substantive adjustment in the average value of private cars, suggesting there has not been a substantial crowding-out-of-the-poor effect.

Short video of delivery guys taking their bikes into the subway to avoid the toll.

More success stories from NYC congestion pricing.

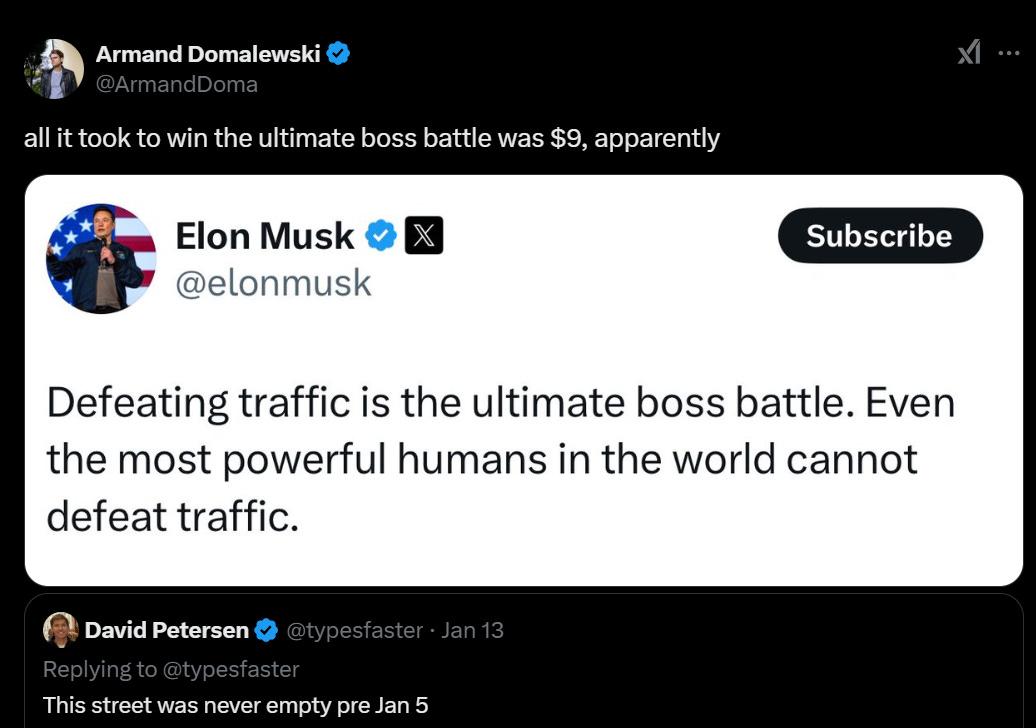

It was the ultimate boss battle?

This is remarkably close to where I live.

Here’s more anecdata.

This one I know instantly, it’s University around 11th Street. From what I remember, it’s usually reasonably quiet, there’s no real reason to be on it with a car due to how it interacts with Union Square. Japonica is very good, the Naya is relatively new, that used to be Saigon Market on the left which was solid but closed a few years ago. Tortaria used to be a top place for me but they changed their sandwiches and now I never go there, although I still like the tacos.

The levels of decline in traffic in such pictures presumably involved a lot of selection. Even so, they’re pretty weird.

Some restaurants are offering $9 discounts to drivers to offset the congestion price. This is smart, because some diners will value this far and above $9, they’ll be more likely to choose your restaurant out of tons of options, they’re spend more freely, and it may even increase the tip by $9 or more out of appreciation. Those from outside the zone are on average poorer and are worse at knowing which places are good (including because they try less often) so this is also smart price discrimination.

Note that some of the discounts are simply traditional special deals with an excuse – Sushi by Bou has a discount code, Shake Shack has a code for a deal that costs $9, Clinton Hill is discounting everyone, that’s 3 of the 6 offers. Also note the expiration dates on the deals, and that by percentage about 0% of restaurants are doing this.

Tyler Cowen’s larger point was also interesting.

Tyler Cowen: I am not suggesting that will be the typical equilibrium, as it should demand on elasticities of demand and supply, and also the time horizon over which you consider adjustment.

But do note that if you are a NIMBY vs. YIMBY type, you ought to conclude that a lot of the congestion tax will fall on landlords, ultimately, and not drivers.

The New York Times reports that restaurant owners are nervous, as some who do shipping pass the fees on to restaurants, and some of their workers are supposedly driving in every day although the math says almost none of them did before.

Julia Moskin: Jake Dell, an owner of Katz’s Deli, estimated that one-fifth of his employees drive to work, usually because they live in parts of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx that are underserved by public transit.

Drive into work is different from drive fully into Manhattan for work. Katz’s is right by a subway stop (2 avenue on the F) and within reasonable reach of multiple other lines, and where the hell are you parking if you drive in all the way?

Once again here, we get more strange math:

Julia Moskin: Many of his guests drive in from the suburbs, he said, and pay about $20 in tolls and $50 for parking even before congestion pricing. Mr. Mehta said that they are both cost- and safety-conscious, and that forcing them to chose between spending more for an evening out or braving public transit will keep them out of Manhattan altogether.

So that’s $70 for tolls and parking, or $79 for tolls, parking and the congestion price, purely to come eat a meal that likely costs ~$200, rather than eat locally or take mass transit. Are you telling me they’d much rather pay the $70 and have the extra traffic at the bridges and tunnels and will travel in far less? That does not actually make any sense.

Similarly, the same article complains about a minimum wage hike from $16 to $16.50, and notes that someone was having trouble getting dishwashers at $29 an hour. I’m no fan of the minimum wage but if it doesn’t remotely bind, who cares?

What I presume matters most is the congestion tax on trucks (which is more than $9) that deliver the supplies. That will make the trucks more efficient, but it is also a charge that will need to be passed on in some form, to some combination of landlords via lower rent in the long run, and to customers.

Those customers are the residents of Manhattan, who essentially everyone agrees are made better off by all this. Note that trucks delivering to grocery stores face the same charges, so the marginal cost of dining out likely won’t change, and the percentage charge might even go down. Which means that the long run amount of dining out plausibly goes up.

To the extent that the tax incidence falls ultimately on landlords, that makes congestion pricing even better. Note that previously, Tyler Cowen framed congestion pricing as good for Manhattan residents and bad for visitors. One could ask ‘which is it’ and it could be different for residential versus commercial.

Normally one would worry that a tax on landlords and buildings would reduce the supply of buildings. But in the case of New York City for most commercial and retail space, the supply is fixed – there are only so many places to put it, and they are going to be full no matter what. For residential, by Cowen’s model and also my own, rents and sale prices should go up rather than down, as improved experience outweighs the cost, and this would hold true even if we correctly priced trips within the zone at $9 (and even if we also priced taxi rides accordingly as well).

Both children and adults do not view social resources like love and trust as zero-sum, or at least they view them as ‘less zero-sum than material resources like stickers.’ Well, I certainly would hope so, these are very clearly not zero-sum things in most contexts. In other contexts, there are obvious competitive elements. In my experience both adults and children seem reasonably good and knowing the difference most of the time?

Their explanation is weird:

Abstract (Kevin Wei and Fan Yang): Perceived renewability of resources predicted lower levels of zero-sum beliefs, and both social and material resources were perceived as less zero-sum when presented as renewable compared with nonrenewable. These finds shed light on the nature and origins of zero-sum beliefs, highlighting renewability as a key mechanism and a potential intervention for reducing competition and promoting cooperation.

I mean, I guess, in some senses, for sufficiently strong renewability, especially if we are accessing the resource at different times. But this feels so off, some sort of buzzword or applause light trying to fit its square peg into a round hole.

The key element, I am guessing is, going out on a limb… actually not being zero-sum? Which sometimes has causal factors or correlates that can look like ‘renewability.’

Not making enough from your videos on YouTube? Post them on PornHub!

Zara Dar: People may not know this, but I publish the same STEM videos on both YouTube and Pornhub. While YourTube generally generates more views, the ad revenue per 1 million views on Pornhub is nearly three times higher.

There ‘aint no rule’ that PornHub videos need to be porn, and the reviews are mostly very positive and much more informative than YouTube’s since you get percentages. Unfortunately, there are now a bunch more states where this won’t work, thanks to PornHub pulling out in the face of new ID laws.

Of course, there’s always the danger of audience capture.

Zara Dar: After my last video went viral announcing I had dropped out of my PhD to pursue OnlyFans and teaching STEM on YouTube full-time, I made over $40k on OnlyFans-more than my previous annual stipend as a graduate student. While most of us don’t pursue graduate studies for the money, it’s terrifying how underpaid and undervalued researchers are in academia.

It sounds like Twitter might actually give us knobs to adjust the algorithm?

Elon Musk: Algorithm tweak coming soon to promote more informational/entertaining content. We will publish the changes to @XEng.

Our goal is to maximize unregretted user-seconds. Too much negativity is being pushed that technically grows user time, but not unregretted user time.

We’re also working on easy ways for you to adjust the content feed dynamically, so you can have what you want at any given moment.

Paul Graham: Can you please stop penalizing links so much? They’re some of the most informative and entertaining content here.

One of the most valuable things you can do for people is to tell them about something interesting they didn’t know about. Links are often the best way to do that.

I strongly support Paul Graham and everyone else continuing to hound Elon Musk about the links unless and until Musk reverses course on that.

I also want to note that ‘unregretted user-seconds’ is a terrible goal.

Your Twitter thread should either be a few very long posts, one giant post, or a true thread where the posts are limited to 280 characters. Otherwise you’re making people click on each Tweet to expand it. Especially bad is when each one is slightly over the limit. Yes, Twitter should obviously display in a way that fixes this, but it doesn’t.

Telegram has greatly ramped up its data sharing with U.S. authorities, in the wake of the arrest of CEO Durov.

The Chinese version of TikTok is called Little Red Book. We know this because its creator, whose name is Mao (no relation!) gave it the name of three Chinese symbols that mean ‘little,’ ‘red’ and ‘book.’ The fact that he’s trying to claim this ‘referenced the colour of his prestigious university and his former employer, Bain Capital, both bastions of US capitalism’ and that he calls any other association (say with Chairman Mao’s ‘Little Red Book,’ one of the most printed books of all time) a ‘conspiracy theory’ only makes it that much more galling. Also see this.

Everything about the way the TikTok so-called ‘ban’ that was never a ban ultimately played out screams that we were correct to attempt to ban TikTok, and that we will regret that due to corruption we failed to do so. TikTok demonstrated, in so many ways, that it is toxic, and that it is an instrument of foreign propaganda willing to gaslight us in broad daylight about anything and everything, all the time – including by doing so about the so-called ban.

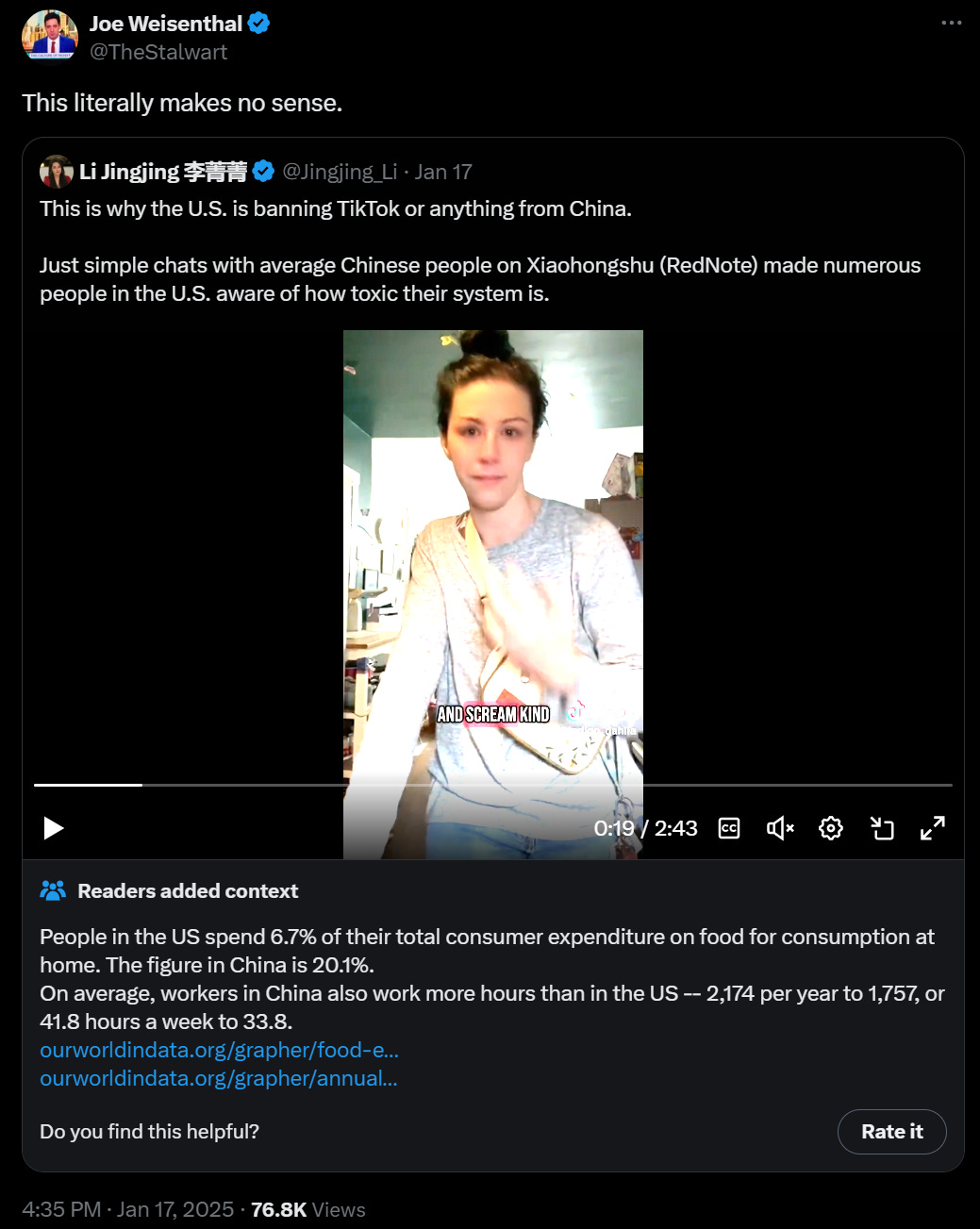

One of their favorites is to push claims about how great China is and how awful America is, especially economically and also in terms of freedoms or ethics, that are mostly flat out factually absurd. She says ‘what do you mean in other countries they don’t have to spend 20% of their paycheck on groceries?’ and ‘in other countries everyone can own homes’ and ‘what do you mean people in China work one job and they don’t even work 40 hours’ in tears.

It means they are lying to you. Also that your consumption basket is completely absurdly rich compared to theirs and if you had to consume theirs for a month you would want to throw yourself out of a window.

This from Richard Ngo rings true to me:

Roon: the thing about America is that its clearly always functioning at like 10% of its power level due to the costs of freedom and yet manages to win anyway due to the incredible benefits of freedom

Richard Ngo: This also applies to people. A significant number of the most brilliant people I know avoid self-coercion to an extent that sometimes appears dysfunctional or even self-destructive. But it allows them to produce wonders.

This effect seems particularly concentrated amongst Thiel fellows (e.g. @nickcammarata, @LauraDeming). @Aella_Girl and @repligate are also examples.

I myself am halfway there but still want (for better or worse) to be more rigid than most of the people I’m thinking of.

Scott Stevenson: Are you sure they avoid self-coercion? They may be very disciplined and embrace illegibility. These look similar but they’re different. You can be disciplined and highly illegible.

Note that America could function at like 20% instead of 10% without sacrificing any of its freedoms, indeed by allowing more freedoms, and thus win more, but yeah.

My case is weird. I do things through willpower all the time, and I don’t really have long periods of ‘being off’ or anything like that, but ultimately everything is because I want to do it, at least on the ‘I want to use the willpower here’ level. I’m fortunate to have been able to structure around that. And still, I feel like I waste so much time.

Richard Ngo: Hypothesis: for many people one of the main blockers to the radical non-coercion I describe below is their pride in their ability to endure pain.

When self-discipline is a big part of your identity, even “having fun” often involves seeking out new types of adversity to overcome.

Clearly the ability to overcome adversity can be extremely valuable (and developing more goal discipline is one of my main aspirations for the year).

But when you have a really big hammer you’re really proud of, everything looks like a nail, even the parts of yourself in pain.

This thread was sparked by me trying some laps in a pool and wondering “why on earth does anyone do endurance exercise when they could play sports instead for all the same health benefits and 10x the fun?”

I’d also draw a big distinction between pain and adversity. They are not the same.

Robin Hanson: “What we have now is a perverse, frictionless vision for art, where a song stays on repeat not because it’s our new favorite but because it’s just pleasant enough to ignore. The most meaningful songs of my life, though, aren’t always ones I can listen to over & over. They’re there when I need them.”

And how exactly can any music system tell that the marginal value of a particular listen is unusually high? If the only signal it gets is whether you listen, all it can tell is that that marginal value is above your other options.

[Twitter] has similar issues.

If all you know are how many times a song has played, then yes, all you can do is use the Spotify formula of rewarding the number of times songs are played.

I am an extreme version of this. The vast majority of my music streaming hours are rain sounds, literal white noise I use to help me sleep. I don’t want all my streaming dollars going to that.

The answer is to offer other forms of feedback.

One can start with the tools that already exist by default. How are users selecting songs? Should we treat all those plays equally?

Here are some basic ideas along those lines.

-

We could weigh songs a user likes (the plus icon) or has added it to their music collection more, perhaps much more, than songs where the user doesn’t do that.

-

We could rate manually selected plays, where the user uses a playlist they created or selects a particular song or album themselves, more than songs autoselected or off of system generated playlists.

-

We could downweight songs played in long sessions without user interaction, especially if those songs are being looped.

-

We could reward songs more if the user then seeks out the artist, or otherwise shows related interests.

-

We could draw distinctions between song types in various ways.

You can also ask the user to tell you what they value?

Suppose there was a button you could click that said ‘support this artist.’ Each user can select any set of artists they want to support each month, and some of their allocation of payments gets divided among whichever artists they select. I expect this would be super popular, and help reward real value creation. Or you could get one reward token per day, week or month when you listen. Or maybe it appears at random while you’re listening, and you have to notice and click it for it to count.

The downside of course is that there would be various schemes to mine that revenue, perhaps offering to split it with the user, and people starting fake accounts to get the revenue from themselves and their friends, and so on. You would need safeguards. It would need to be fully anonymous. Perhaps you could only get support revenue at some proportion to some calculation based on your unique streams.

That’s the five-minute-brainstorming-session version. We can do a lot better.

If we actually want to do better.

What should we think about claims regarding ‘Operation Chokepoint 2.0’?

For all things in the category that includes debanking, the person I trust most is Patrick McKenzie. He wrote an epic 24k word post on the overall subject. Here is his Twitter thread summarizing.

I see no reason not to believe the things in that post.

So, as I understand it:

Did crypto and people involved in it get debanked rather broadly? Yes.

Did the government encourage this, including some Democratic officials using various forms of leverage to cause more cracking down? Yes.

Did they intentionally kill Libra using their leverage? Yes.

Did the individuals in crypto often try to use personal accounts as business accounts, leading to the part where the individuals got debanked too? Hell yeah.

Has the SEC largely enforced the obviously-true-under-the-actual-law-as-written fact that almost all crypto tokens and certainly all the offerings are securities, while not giving crypto any way to comply whatsoever that is compatible with their technology and business models? Well, yeah, to a large extent that did happen.

Are crypto people trying to use this moment, in its various aspects, and the label ‘Operation Chokepoint 2.0,’ to try and force banks to allow them to operate with essentially no supervision, allowed to essentially do all the financial crime, as Patrick McKenzie claims? And, also as Patrick McKenzie lays out at the end, do they want to force the SEC to allow them to issue arbitrary tokens they can market to ordinary Americans via every form imaginable to both make every moment of our lives filled with horrid spam and also try to extract trillions of dollars, largely from unsuspecting rubes? I mean, that does sound like what they would try and do.

Are banks ‘part of the government’ as Marc Andreessen claims? Do we ‘not have a free market’ in banking? Well, yes and no, banks certainly have a lot of rules to follow and when the regulators say jump they have to ask how high, but centrally no, that’s not how this works in the way he’s trying to imply, stop it. I’m sure Patrick McKenzie would write a lot of words on that prompt explaining in excruciating detail exactly how yes and how no, that he still felt was highly incomplete.

The question this leaves us with is, how far beyond crypto that did this go? Marc Andreessen claims that they also debanked “tech startups and political enemies.” But this is a highly unreliable source, very prone to hyperbole and exaggeration – he could in both cases essentially again just mean crypto.

The one other case I know about of a ‘political enemy’ being debanked plausibly for being a political enemy is the case of Gab (which definitely happened regardless of what they did or didn’t do to provoke it), but what else do we have? How systematic was this? Are there any known cases where it was, as he implied, the government going after AI startups because they are (non-crypto) AI startups?

And if there are such other cases, does it go beyond a few overzealous or partisan people in some compliance departments acting on Current Thing on their own, of which one can doubtless find some examples if you look hard enough, as Patrick McKenzie lays out?

Especially, did partisan officials engage in a campaign to debank political enemies? Marc Andreessen claimed yes in front of 100 million people.

Patrick McKenzie points out that if that was true, the world would look very different. That these claims seem to be almost entirely spurious.

I am actually asking, in case there is stronger evidence that Marc Andreessen was not, to use another of Patrick’s terms, bullshitting as per his usual. There are some very bold claims being thrown around far too casually, that are very Huge If True.

I do think we should have a full accounting of exactly what happened, and that this is important. I do worry that the ‘full accounting’ we will actually get will be written by certain rather unreliable agenda-laden narrators. For details, again, Patrick’s account seems like the best we have right now.

Marc also offered this thread of longform posts on debanking that he approves of.

Also it is worth noting that this style of paranoia goes both ways, as in Jon Stokes reporting that he’s in a left-wing group that he says for-real-no-really expects the Trump administration to debank women like in The Handmaid’s Tale. Yeah, no.

Dennis Porter’s account seems likely correct too, as I understand this, government applies soft power to imply that if you bank people in certain industries (centrally crypto here at least sometimes, but there’s a bunch of others saying ‘first time?’) you’ll get investigated, so the banks don’t want the trouble.

What I don’t understand is the label ‘tech founders’ as people who are being debanked, independent of issues with crypto. Yes, Silicon Valley Bank went under, but to the extent that was intentional it was quite clearly about crypto. I don’t see any such pattern substantiated in any concrete way, and when I asked o1, GPT-4o and Claude they didn’t find one either. Patrick McKenzie seems unaware of one, except insofar as a16z portfolio companies tended to engage in actual financial shenanigans and get debanked for them sometimes, which frankly seems like the kind of thing he would invest in. As far as I can tell, this was basically bullshitting.

For other targets I refer you to this helpful chart:

I’d also use this opportunity to agree strongly with Brian Armstrong here that Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations are nowhere near passing a cost-benefit analysis. They do indeed have impose massive costs and make many things so much more annoying as to make people give up pro-social activities outright, I suspect his ~$213 billion global annual cost estimate here is actually rather low. One of those costs is, indeed, a lot of the debanking going on.

The primary intended effect, of course, is exactly in the deterrence of activity and cost of compliance. You only intercept 0.2% of criminal proceeds, but if that makes all sorts of crime more expensive and inconvenient (e.g. you Better Call Saul and he takes 15% up front and also you spend a bunch of time dealing with a car wash). So in an important sense you’ve lowered criminal returns and logistical ability quite a lot.

This in turn should greatly reduce crime. We impose all sorts of regulations on pro-social and legal activity, if criminals could use the banking system with impunity the balance might get totally out of control. We could easily be preventing a ton of counterfactual money laundering activity. Or it could be not that impactful versus a much lighter touch version, and we should be 80-20ing (or even 90-10ing) this.

I’m very confident we’re spending at least double (in terms of money and inconvenience) what we should be spending on this, as opposed to our underinvestment in many other forms of crime prevention, and probably a lot more than that. The banking system puts up way too many barriers in places that have very low probabilities of stopping either errors or crimes, when it could simply track activity instead. And yes, if we keep all this up and things are too annoying, we drive people to alternative systems.

I wonder how or how much this is related to it becoming easier over time to get various documentation from banks, as various frictions go away perhaps they find other places to appear because they were load bearing.

Conrad Bastable has thoughts here about the question of ‘do you destroy debanking and other government abuses or do you use them on your enemies now that you have power?’ My note here is that he puts Marc Andreessen on the ‘destroy the ring’ side of the debate, whereas I see him as very much saying to use the ring. Perhaps not to the extent Vance wants to use ‘raw administrative power’ to bully everyone and everyone, but quite a lot.

Men love quests. Give them quests. Then say thank you rather than sorry.

Nadia: You can literally just email a museum and ask them to connect you to exhibit creators and geek about their art with them – what a beautiful and open world??!

Ryn: Yes! I work in heritage and run an exhibition programme and this is true. Art and culture can have a huge influence on people’s lives, but we never know unless you tell us. It absolutely makes my day when I get those types of emails.

Thomas Delvasto: It’s pretty dope. Most creators and professors love that shit too.

Yatharth: every time i’ve done this they’ve usually been dying to talk to me 😭

i assumed they would be too busy or uninterested

Speaking from experience: Creators are by default yelling into the void, and even at a surprisingly high level hearing they’re appreciated is kind of amazing, it’s great to interact with fans, and also the data on exactly what hit home helps too.

There is a limit to how much of this one wants, but almost no one ever does this, so you probably don’t hit that limit until you’re someone rather high level.

In general, you can reach out to people, and they remarkably often do respond. When I don’t get a response at all, it’s typically a very high level person who is very obviously overwhelmed with requests.

Google finally incorporates eSignature capability into Google Workspace.

Japan has a service called ‘takkyu-bin’ that will forward your luggage on ahead of you to your next hotel or airport for about $13.

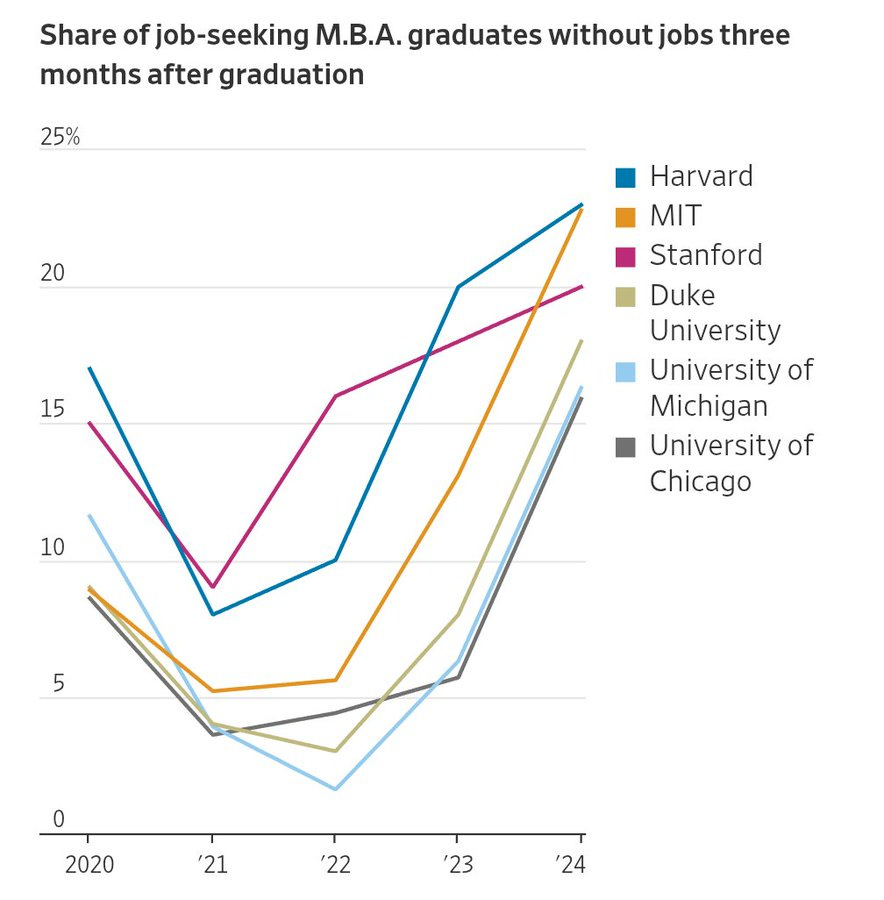

Graduates of MBA programs more likely to be unemployed for longer after graduation.

Paul Graham: Prediction: This is a secular [as in not cyclical] trend. The pendulum will never swing back.

Steve McGuire: Seems likely.

“Employers don’t hire as many MBA grads during the school year, a tactic that was common two years ago. Now, they recruit smaller numbers closer to graduation—and afterward. “

“Amazon, Google and Microsoft have reduced MBA recruiting, as have consulting firms.”

“Going to Harvard is not going to be a differentiator. You have to have the skills.” —Harvard Business Schools’s Career and Professional Development Director

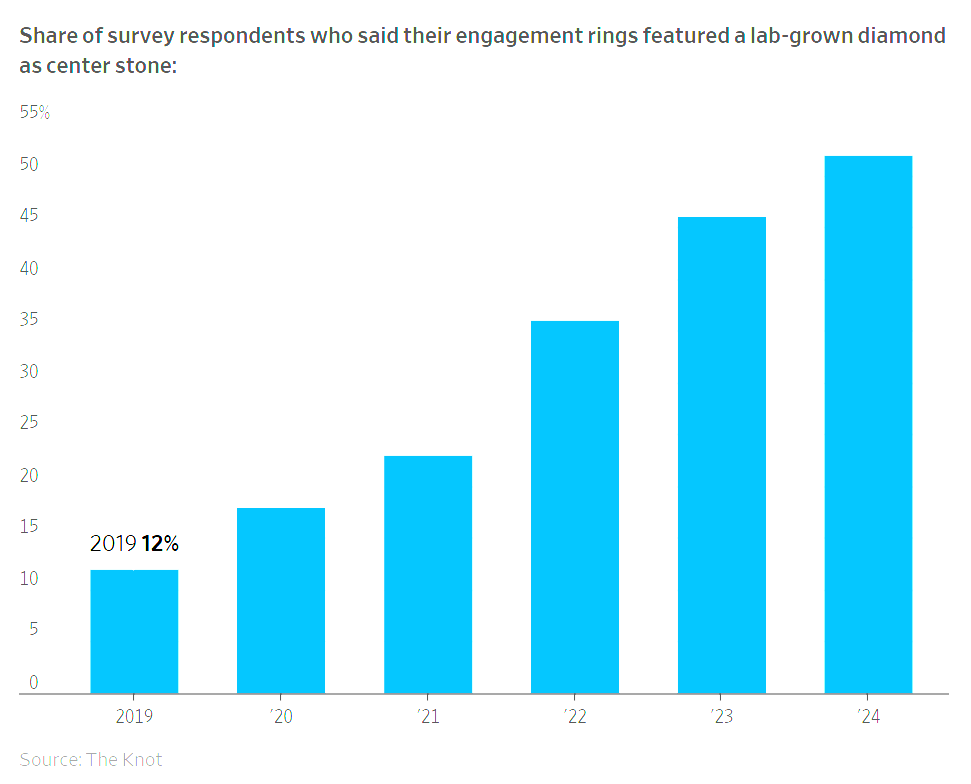

A majority of diamond engagement rings now use artificial diamonds, up from 19% in 2019, with prices for artificial diamonds falling 75% this year.

You have to love how De Beers is trying to spin this:

Jinjoo Lee: What might it take for the shine to return to natural diamonds? Miners like De Beers are hoping that the widening price gap for the lab-grown variety will naturally lead consumers to consider them a completely different category, not a substitute.

For those who don’t know, if your flight seems oddly expensive, such as in this example $564 LAX-STL, I don’t recommend it, but you can (if you dare) try and do much better by booking a flight with a layover at your true destination, such as LAX-STL-ATL, and not using the second leg of the flight. By default this does mean you can’t check bags, but with a long enough layover there’s a claim you can cancel the second leg after the first one and get your bags back. The catch is that technically this violates the terms of service and they can sue you for the fare and void your miles and in theory ban you also cancel your return ticket (so if you do this, you presumably want to do it with two one-way tickets) and so on.

This seems brilliant:

This too: For $20 you can buy better wheels for your office chair, if you want better ease of rolling, since the default wheels are probably rather terrible.

Blast from the past (March 2024): The Best Tacit Knowledge Videos on Every Subject. I have never learned things this way, and generally hate video, but I could be making a mistake.

Paul Graham essay on The Origins of Wokeness.

Dwarkesh Patel offers notes on China, recommended if you haven’t read it yet.

Benjamin Hoffman presents The Drama of the Hegelian Dialectic. I think he tries to prove too much here, but the basic pattern is very real and important, and this seems like the best explanation of this that we have so far.

Patrick Collison on reading ten historical novels in 2024. He recommends Middlemarch, Bleak House, Karenina and Life of Fate. It is telling that he includes a passage to show what a great wordsmith Dickens was… and I couldn’t make myself finish it, I was so bored. That’s not to say it was bad wordsmithing, I can’t even say, but there was something there I was supposed to care about, and I just didn’t.

JP Morgan returns to full in-office requirements for all employees.

What kind of thing is an attention span or focus?

Visakan Veerasamy: I’ve personally helped several hundred people with their problems at this point and one of the most widespread issues was they were previously thinking of focus or attention span as something fungible, like a commodity, when it always turns out to be more like love and caring.

He links to Jay Alto giving recommendations on how to improve on this: Sleep, bianural beats right before work, warm-up, 90-minute work sessions, warm-down, supplementation of (Omega 3s, Creatine, Alpha-GPC and L-tyrosine), meditation and an afternoon ‘non-sleep deep rest). This all most definitely falls under ‘do what works for you,’ a lot of this I can confirm wouldn’t help me, but I have no doubt it works for some people.

Tip rates at restaurants slightly declined and are now around 19.4% from a high of 19.8%. The whole system is fundamentally broken, since tips correlate with money spent and whether the person adheres to social norms, and vary almost none with actual service, plus people are abusing the system by asking for tips anywhere and everywhere, which makes some people pay up everywhere and others throw up their hands and pay nowhere. But I don’t know how we get out of this trap, and restaurants that go tipless learn that due to customer perception of prices they can’t sustain it.

Robin Hanson, never stop Robin Hansoning, we love you:

Robin Hanson: Nothing makes food taste better than not eating for many days before. Yet how often do supposed “foodies” use this time-tested trick to achieve max food pleasure?

My explanation: they are more interested in signaling taste than in acquiring pleasure.

No doubt that is part of it, and people often want the symbolic experience of having eaten the good thing more than eating the thing they would actually enjoy, or especially that they would enjoy in the moment.

But also fasts are rather expensive for most people, and it’s not obvious the gains are worthwhile, and people are bad at planning ahead and discipline.

I do indeed often fast for 24-36 hours, occasionally 48, before a big or special meal, or purely because I can only eat so often. But I have the practice, and it truly does not bother me. My wife is an example of someone who absolutely cannot do that.

I do agree strongly with his opt-repeated call Towards More Direct Signals. Or signals are often indirect, and costly. Would it not be better for them to be direct, and not costly, but still credible? Alas, we do not want to admit what we are doing to others or even ourselves, and punish overt signaling and demands for it, so this is difficult.

He points to the Nordics allowing the public to access tax records, as a way to force everyone to credibly and freely signal wealth, and suggests we could do mandatory IQ tests and paternity tests and such as well. This makes sense in theory. If we inflict a price on people who signal too cheaply, requiring cheap signals can be a win for everyone, or at least everyone who wasn’t successfully fooling us, and faking the signal.

The biggest problem is that our desires, even hidden ones, are not so simple. Do we want to signal our wealth? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. In the never-stop-Robin-Hansoning, we have this from the comments.

Daves Not Here: High income numbers make you a target for burglary, kidnapping, or home invasion. At that point, you might want to signal that you consume a lot of private security services.

Robin Hanson: I’m happy to have that stat included in your public stat profile.

No, that’s even worse! The issue is not that you want to signal that you consume the services. The issue is that you actually need the services, and actually effective security is super expensive not only in money but in lifestyle. If you have billions in crypto – which to be very clear I do not – there are situations in which you want that known, and others in which you really, really don’t.

Similarly, often you want to ‘live as a normal person’ without wealth coloring everything. If you make a friend, or date someone, and they know you’re rich, how do you know they aren’t after your money? That’s a key reason why ‘who you knew before you made it’ is such a big deal, and why the wise ultra-wealthy person often doesn’t tell their dates the full extent of their situation. For a fictional example, see Crazy Rich Asians.

There are also issues of fairness norms, and the ‘evil eye.’ A key failure mode is when people are too aware of when others have additional wealth or income, and can thus create social obligation to friends, family or community to spend that, imposing very high effective marginal tax rates, often approaching 100%. If people then expect you to keep producing at that level, it can be even worse than that.

Or you could simply face a lot of price discrimination, and a lot of solicitation for gifts, spending and investment, along with attempts to scam, defraud or rob you, have the specter of money over every interaction, and generally feel adversarial all the time.

Thus there are common real situations where additional wealth or income that people know about is much less valuable or even an albatross, and everyone works hard to hide their wealth, or even intentionally avoids acquiring it in the first place. If you cannot hide your wealth, the envy and fairness instincts run deep, and people might well punish you in various ways for the signal even if you didn’t intentionally send it. These mechanisms keeps many cultures mired in poverty.

I’d also note that my experiences in the nonprofit world show a large amount of a version of this problem. Donors often only want to help based on their marginal impact, and want to ensure you ‘need the money,’ so everything gets twisted to ensure that without marginal donations a lot of value would be lost. And That’s Terrible.

Another problem is Goodhart’s Law. People are going to respond to incentives. If certain signals are required, then people will warp their behaviors around those signals, to get the results they want, in ways that could themselves be massively costly.

I final problem is that some amount of strategic ambiguity is important to social interactions. In a typical group you would know who is highest and who is lowest in status, but there is often deliberate effort to avoid creating too much clarity about status within the middle of the group to maintain group cohesion and let everyone tell themselves different stories – see The Gervais Principle. And when things get quantified, including changes in status from actions, then that’s a lot like attaching money to those transactions, another reason many things want to be ambiguous, and also of course often you want to measure signaling skill itself in various ways, and so on.

So you often want to be able to signal ambiguously, and with different levels of clarity, to different people, about things like wealth but also things like intelligence. And you want to have some control over methods of that.

The correct Hansonian response to these caveats is to ask when and where these trends go in one direction versus the other, and why we should expect such objections to dominate. And to point out that we should expect to have way too little mandated clarity versus what is optimal, for the reasons Hanson originally gives, even if the results of marginal clarity are mixed and decreasing. These are very strong objections.

I endorse the principle here from Kelsey Piper that if someone is rhetorically endorsing mass murder or other horrible things, one should assume the people involved do indeed endorse or at least are willing to be gleefully indifferent to mass murder, far more than you might thin,, no matter how much they or others explain they are using ‘dramatic license’ or saying it ‘to make a valid point,’ and this applies in all directions.

Kelsey Piper: Some people have really invested their identities in “having any standards of decency at all is leftist” and I don’t think this is going to go as well as they believe it will.

If a leftist said that we should guillotine all the rich, deport all the MAGA supporters, and take the vote away from men, would you go “hey, it’s dramatic license, calm down”? I think that everybody should be held to the standard of not calling for atrocities.

J.D. Haltigan: I would simply pass it off as standard leftist fare.

Andrew Rettek: People being tolerant of those sorts of statements and dismissing my unease with them back in 2018-2019 is a big factor in why I stopped participating in a lot of discord channels.

Kelsey Piper: I made the mistake of assuming some leftist rhetoric was dramatic license not meant literally and then learned that no, those people sincerely supported Hamas and shooting CEOs. I have learned from that mistake.

I think that for the most part, people jokingly declare that their political agenda is mass murder usually actually favor mass murder, or are at least gleefully indifferent to it.

Virtue is good, vice is bad, society isn’t a race to the bottom and the people who are racing to the bottom won’t like what they find there.

No Refuge in Audacity. Also, if someone says that endorsing very horrible proposals is ‘standard [X]-ist fare’ a la Haltigan here, and you find yourself thinking they are right about that, then you should draw the obvious correct conclusions about standard forms of [X] and act accordingly.

The other problem is, if you start out saying such things ironically or as hyperbole, especially if people around you are doing the same, you all start believing it. That’s how human brains work.

Ben Landau-Taylor: It is psychologically impossible to hold any position ironically for longer than 12 hours. If you start saying something as a joke, then you will come to believe it sincerely very, very soon.

Science Banana: true but it has good and bad uses IMO. Irony is a frame that lets us try out a lot of behaviors and then kick out the frame if we like them.

Ben Landau-Taylor: Yeah this is why the “Skill issue” and the “Yet. Growth mindset” people actually end up getting better at stuff and living with more thumos.

The title of the excellent post by Sarah Constantin is ‘What Goes Without Saying,’ because in the right circles the points here do go without saying. But in most places, they very much do not, which is why she is saying them, and why I’m repeating them here. Full post is recommended, but the central points are:

-

There’s a real way to do anything, and a fake way; we need to make sure we’re doing the real version. This was actually the subject of my first blog post.

-

It is our job to do stuff that’s better than the societal mainstream.

-

Pointless busywork is bad.

-

If we’re doing something worthwhile, not literally everyone will like it.

-

It’s important to have an honorable purpose; commercial purposes can be honorable.

-

Remember to include the outsiders (and all young people start out as outsiders).

Tyler Cowen directs us to Auren Hoffman’s advice on how to host a great dinner party. I think a lot of the advice here, while interesting, is wrong. Some is spot on.

My biggest disagreement is that Auren says the food does not matter. That’s Obvious Nonsense. The food matters a lot. Great food makes the night, both directly and indirectly. Great food gives people something to enjoy and appreciate and bond over, and will be something people remember, and even if the conversation is boring, you still had great food. Everyone’s in a good mood.

Even more than that, if the food is bad, you feel obligated to eat it anyway to be polite and because it’s there, so it’s often far worse than no food at all. If you structure the food so one can inconspicuously not eat, then food matters much less, as your downside is capped.

If you don’t have good food, you can still rescue the night with great conversation – I would happily have a great dinner conversation minus the dinner.

Of course, you can have a great night of discussion over pizza. Nothing wrong with that. That’s a different type of party, and it has different rules.

All the terrible dinners Auren warns about, and oh boy are they terrible? They all have terrible food. Imagine going to that nightmare charity dinner and auction, except the food is not catering, it is exactly what you’d get at your favorite high end restaurant. So sure, you have to sit through some drivel, but the meal is amazing. So much better. The rubber chicken is integral to the horribleness of that charity auction dinner.

I agree speakers are bad, and that you want people on roughly the ‘same level’ regarding what you plan to discuss, in the sense that everyone should want to meet and talk to everyone else. It’s fine to have someone ‘hold court’ or explain things or what not, too, but everyone has to want that.

I agree that planned conversation can be better than unplanned, but I think unplanned is fine too, and I especially push back against the idea that without a plan a dinner party will suck. If you bring together great people, over good food, it will almost never suck. Relax. It’s all upside from there.

Especially important: Do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Don’t think that if you do a bad job, you will have made people worse off.

The full easy mode is ‘let’s all go to a restaurant and have dinner together’ and there is 100% nothing wrong with choosing to play in easy mode.

I strongly agree that you want one conversation, and you want to keep things small, and you need good acoustics. I don’t think it’s as fatal as he does to have 2+ conversations, so long as each one can hear itself within the conversations, especially since I think 12 is already too many people in one conversation. I think you want to be in the 4-8 person range, hosts included.

Thus yes, the best place is your place, because it’s small.

I also mostly oppose fixed end times, except for a ‘this is when it becomes actually too late for us.’ The night will go on as long as it wants to, and I don’t want to pressure people either to stay or to go.

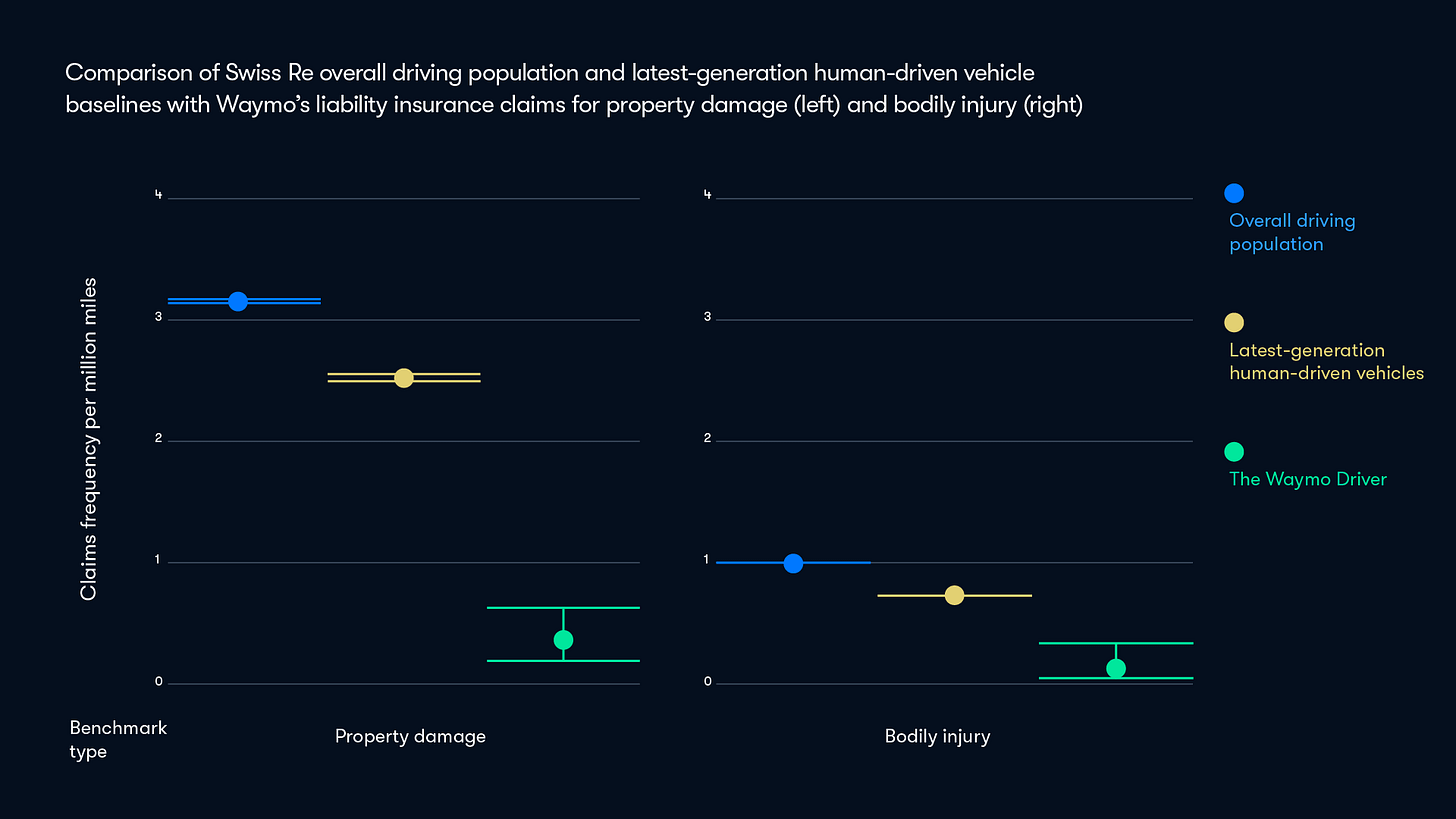

New study from Waymo and Swiss Re concludes their self-driving cars are dramatically safer than human drivers. We’re talking 88% reduction in property damage claims, 92% decline in bodily injury claims. Not perfectly safe, but dramatically safer.

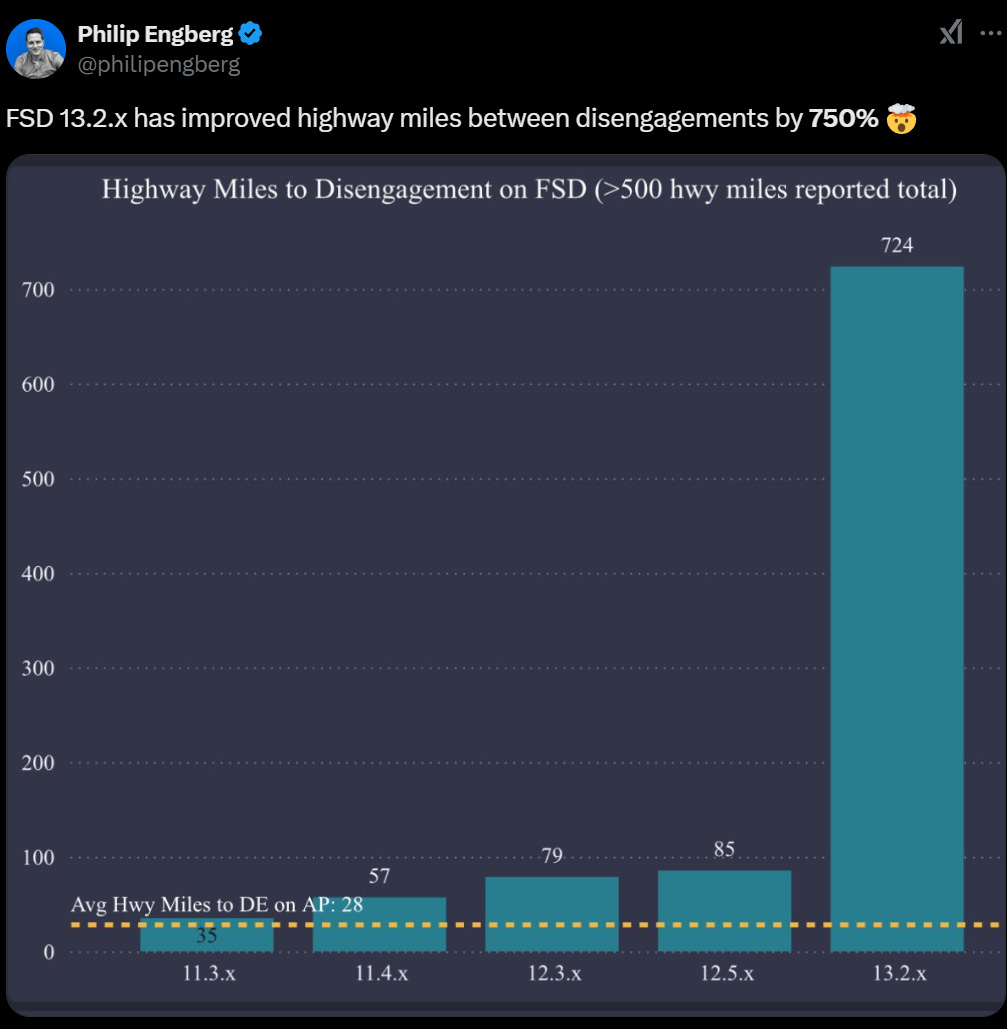

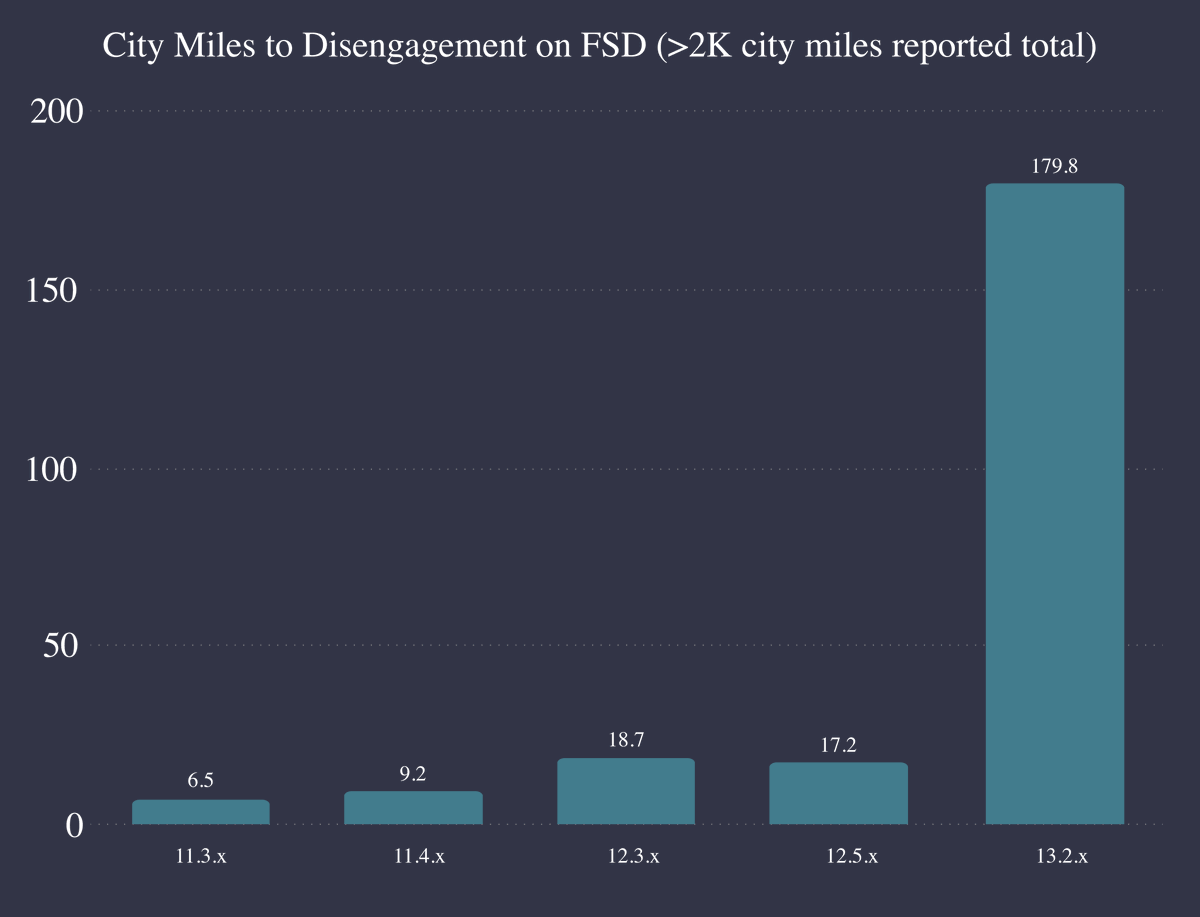

Full self-driving living up to its name far more than it used to, with disengagements down 750% in Tesla version 13.2.x. There’s a huge step change.

This step change feels like it changes the nature of the product. It’s a big deal.

An issue with Waymo is that they cannot easily adjust supply to fit demand. They have a fixed supply of cars. Waymo does use surge pricing anyway, since demand side needs to be adjusted, but they don’t apply enough of it to balance wait times.

A fun little (bounded) idle game.

Nate Silver’s incomplete guide to Las Vegas and getting started in poker. It includes extensive restaurant and hotel recommendations.

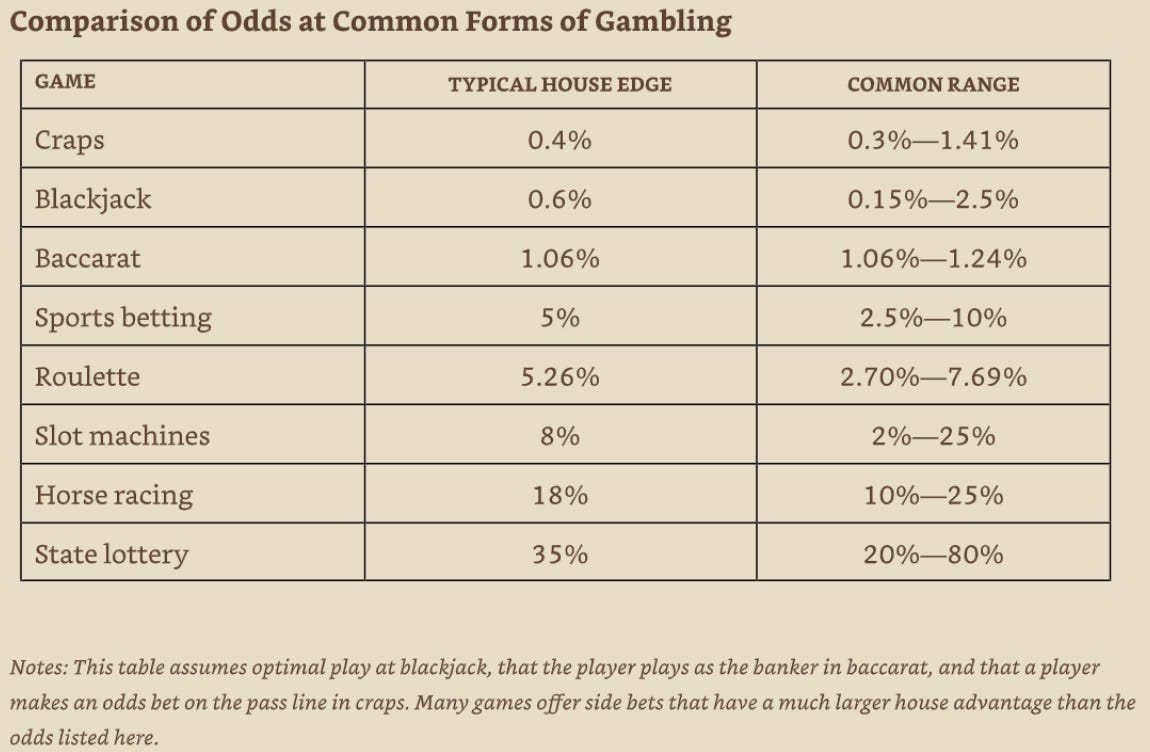

If you ever consider gambling, here is a sign for future tapping:

Note on sports betting: This assumes random betting on a -110 line. You can do much worse if you use parlays or props, or you can actively win if you’re good enough, and quick line shopping helps a lot (probably takes you from -5% to about -2%).

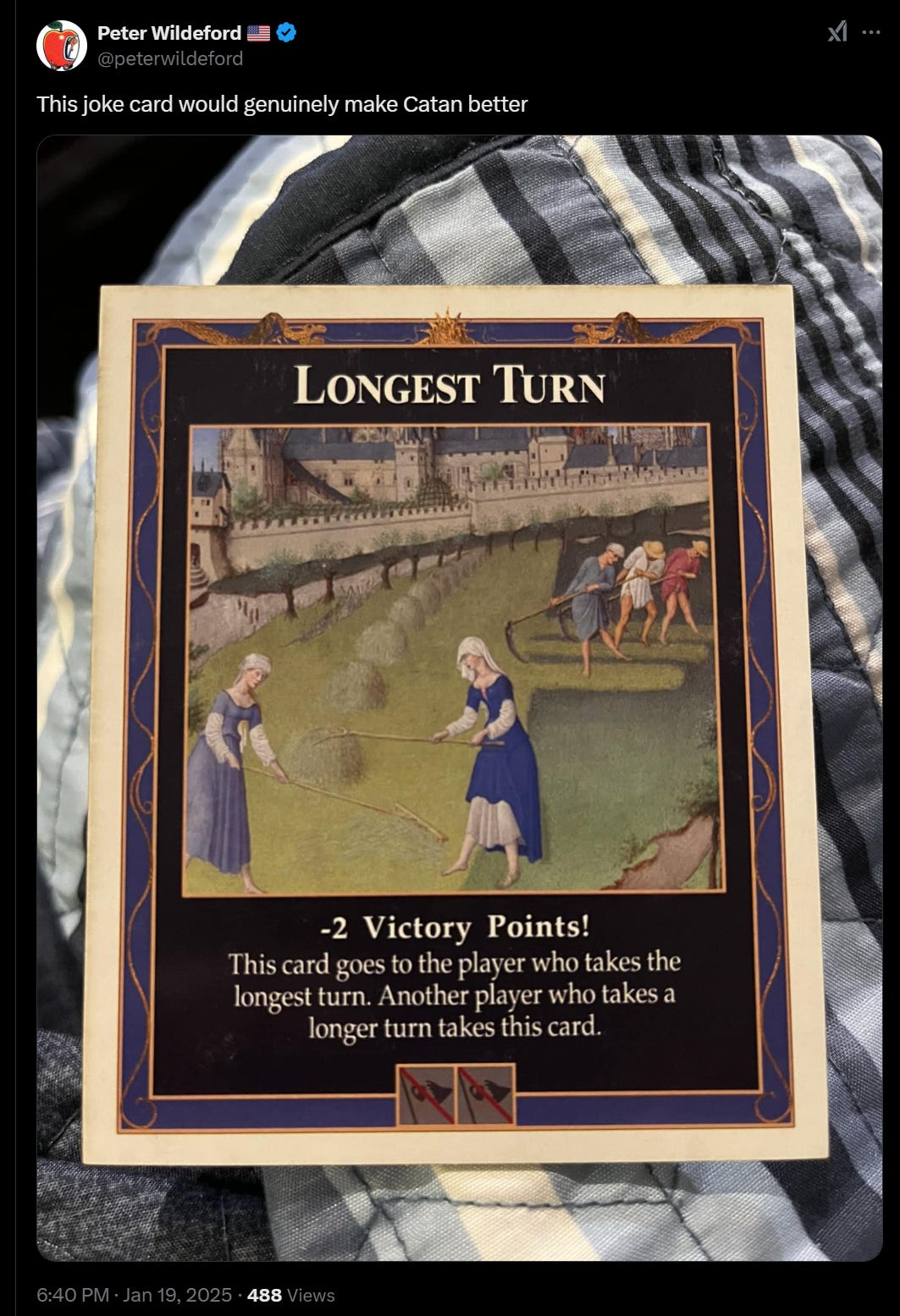

An amazing innovation if you can implement it, I agree -1 is probably enough there.

The issue is tracking the longest turn. Perhaps an AI like Project Astra could do this?

For computer versions of many games, this is easy to implement, and potentially very cool. Alas, it doesn’t guard against someone taking infinite time, and also doesn’t help if someone already has accepted that they’re getting the penalty this game. So it’s not the right complete design, you need something that scales alongside this.

A strong argument that Hasbro should massively increase spending on the Magic Pro Tour going forward. This suggests a 150% prize pool jump. I would go a lot further. Why not a 2,000% jump to $1 million per event, which would still less than double overall costs because of logistical expenses? Magic is a bigger and more popular game than back in the day, and this is still a drop in the bucket. Don’t let the failure of the MPL prevent us from doing the very obvious. Not that many at Wizards don’t know that, but the bosses at Hasbro need to understand.

Netflix mandates that content in its ‘casual viewing’ category continuously have characters explain what is happening. Good. Technically this is ‘horrible writing’ and makes the content worse, but the purpose of this content isn’t to be good in that sense. ‘Show, don’t tell’ is for people who want to focus and pay attention, and overrated anyway. I don’t put shows on in the background, but many others do, and the cost of telling in addition to showing usually is often very low.

This then gets them out of the way so Netflix can also offer Really Good and even Insanely Great content, such as recent verified examples Nobody Wants This and The Diplomat. You can’t watch more than a small fraction of what’s out there, so differentiation is good, actually.

There is a problem, not unique to Netflix, where there are shows that have real merit, but which are presented as casual viewing, and thus waste a lot of time or even involve massive intentional self-spoilers.

The bad-on-purpose genius of Hot Frosty, according to Kat Rosenfield. I love all this on a conceptual level, but not on a ‘I would choose to see this movie’ level.

Aella offers extensive highly positive thoughts on Poor Things (spoilers).

Everybody knows but I can confirm that Shogun is excellent.

The Diplomat is also excellent, now through two seasons, a third is coming.

Severance had an excellent season 1 but I haven’t gotten to season 2 yet. No spoilers.

TV show rating updates: Umbrella Academy moves from Tier 2 → Tier 3 as it only finished okay. Slow Horses goes in Tier 2. Killing Eve goes in Tier 4. In a special split case, Supernatural (Seasons 6-15) goes in Tier 4, but Supernatural (Seasons 1-5) remains in Tier 2, if I had to fuse them I’d split the difference. Similarly, The Simpsons used to be purely Tier 3, will now be Tier 2 (Seasons 1-10) and Tier 5 (Seasons 11+) as a superior approximation. The Bachelor moves from Tier 5 → Tier 3, The Bachelorette at least from Tier 5 → Tier 4, in a pure ‘no I didn’t get it and I was wrong.’

Also I am considering renaming the tiers from 1-5 to S/A/B/C/F as per custom.

The new record for ‘men slept with in 12 hours’ is now 1,057, for some necessarily (given math) loose definition of what counts. My actual objection is that we need clear standards on exactly what counts here. Depending on the answer, this is either a ‘how did you pull that off’ or ‘come on you can at least double that.’

The college football playoff is a rousing success, except that the actual game outcomes could not from my perspective have gone worse. Aside from swiftly dispatching the ACC teams I rooted for did not win a single game. Notre Dame vs. Ohio State with OSU a heavy favorite is the actual worst possible final matchup in all of college football – Ohio State is objectively Them and Notre Dame is my best friend’s Them. Well, as they say, wait till next year.

Tyler Cowen diagnoses the NBA as having an economics problem due to the salary cap. Thanks to the cap, teams can’t be dominant and there aren’t dynasties, so we don’t get the legacies and household names that make people care.

Why should I invest in even my local team if they have to constantly rotate players, and having a shot this year often means gaming the salary cap and thus being bad in adjacent years?

As a fan, I want to root for the same core players over time, and either have ‘hope and faith’ each year or a story about how we’re rebuilding towards something that isn’t a 1-year flash in the pan.

There’s also the problem of taxes, which Tyler oddly does not mention. If I play in New York or Los Angeles, I have to pay much higher tax rates. But the salary cap and max contract are the same. I probably like living in those places, and I probably like the media and marketing and star making opportunities, but this is really rough for exactly the teams you ‘want’ to be good. From the league’s financial perspective, you don’t want Oklahoma City playing Milwaukee in the finals. Imagine a world in which the salary cap and max contract were post tax.

Parity can be cool too, but we also don’t have that. There are fully three teams who have won 75% of their games as of Christmas Eve and four teams averaging at least a +9.5 point differential. And that’s presumably with those teams largely coasting to stay healthy for the playoffs – if the Cavaliers wanted to be undefeated, my guess is they would be.

I would also continue to blame the incentives. The season has too many games, and they matter too little, and the risk of injury thus dominates too much thinking. Sure, the finals of the midseason tournament is worth $300k per player and they’re going to care about that, but it should matter for the fans. Imagine if the midseason tournament came with a Golden Home Game. At any point during the playoffs, one time, you could say ‘we’re playing this one at home.’

Alternatively, this could all be a blip. The NBA had a great season, now it’s having a less great season. These things happen.

Paper claims that top tennis players use inefficient mixed strategies on where to target their serves, and most Pros would win substantially more if they solved for the equilibrium. Partly they’re pointing out that Pros are not perfect at the calculation, which is obviously true. What I think they’re missing, which is common in sports, is that not all points and games are created equal, and that opponents adjust to what you do in ways that don’t snap exactly back when the leverage shows up. So often players and teams will do non-optimal things now to impact future opponent actions, allowing them to be above equilibrium later.

Nate Silver breaks down his opinions on the MLB Hall of Fame candidates. It’s always fun to nerd out like this. I think I’d lean less on WAR (wins above replacement) and similar statistics than he does, and more on intangibles, because I think this is a Hall of Fame, not a Hall of Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence. Mostly I think it’s fine to disagree about magnitudes, and for voters to lean on different aspects.

Except for steroid use. Here I find Nate’s attitude unacceptable and baffling. We are talking about players whose careers were, fundamentally, a bunch of filthy cheating, and in a way that substantially contributed to their success. If that’s you, am never, ever rewarding that behavior with my vote, period, and if you disagree I will think less of you. I felt the same way about the Magic Hall of Fame, and voted accordingly.

The interesting steroid case as I understand what happened is Barry Bonds, in that we believe that he first had a Hall of Fame level career, and then he started using steroids, and then he had one of the best sets of results of all time. To me the question is, can we vote him in purely for the first half, or do we need to not do so because of the second half. But a discount rate of far less than 100%? I can’t agree to that. The same would apply to Clemens, A-Rod or anyone else.

In case you missed it, the same way they missed it.

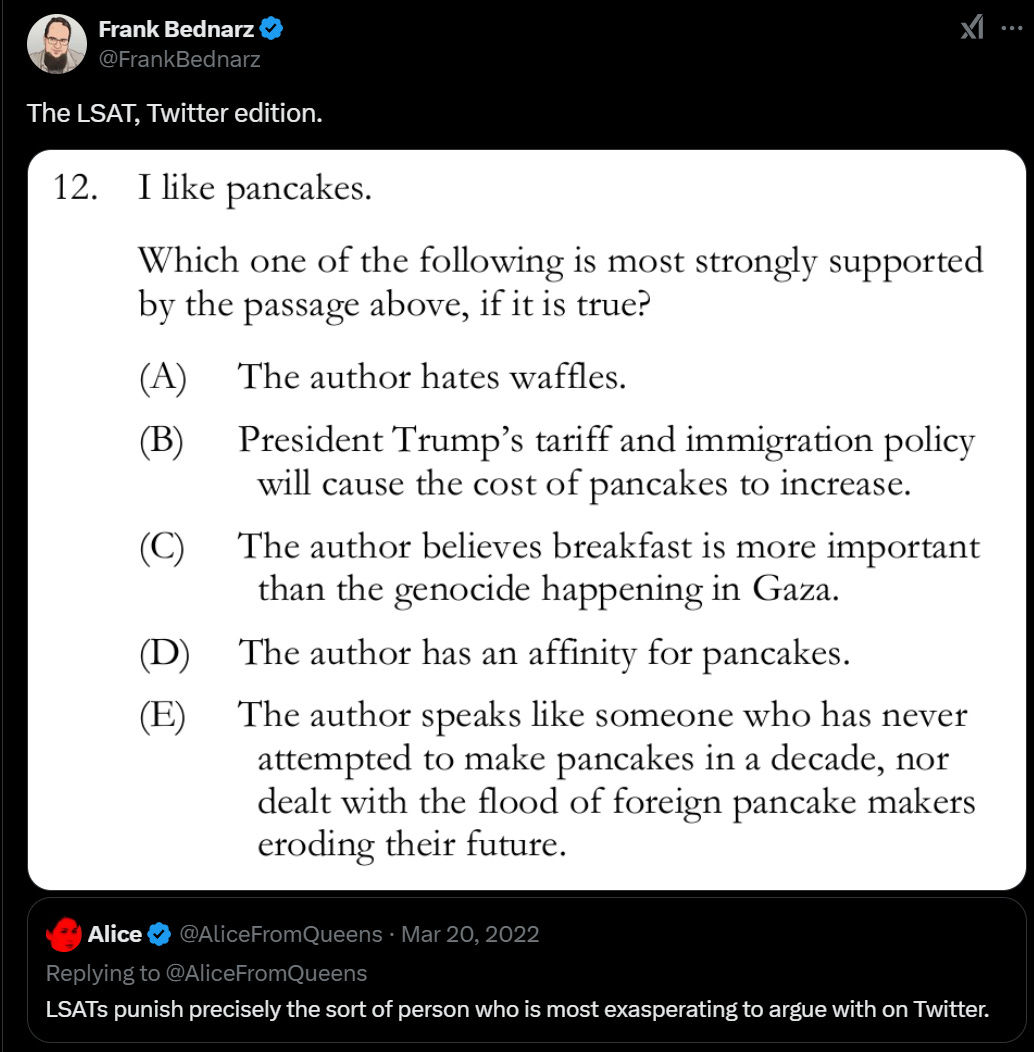

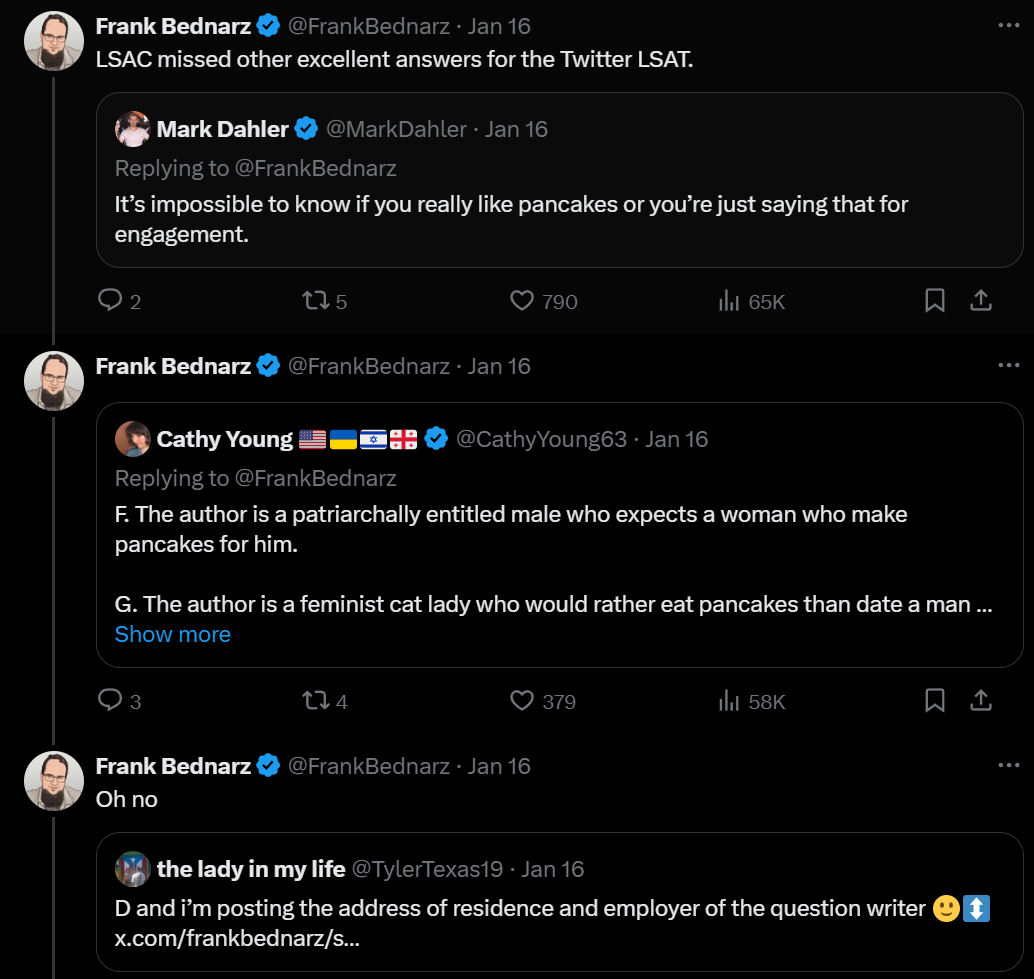

The LSAT remains undefeated.

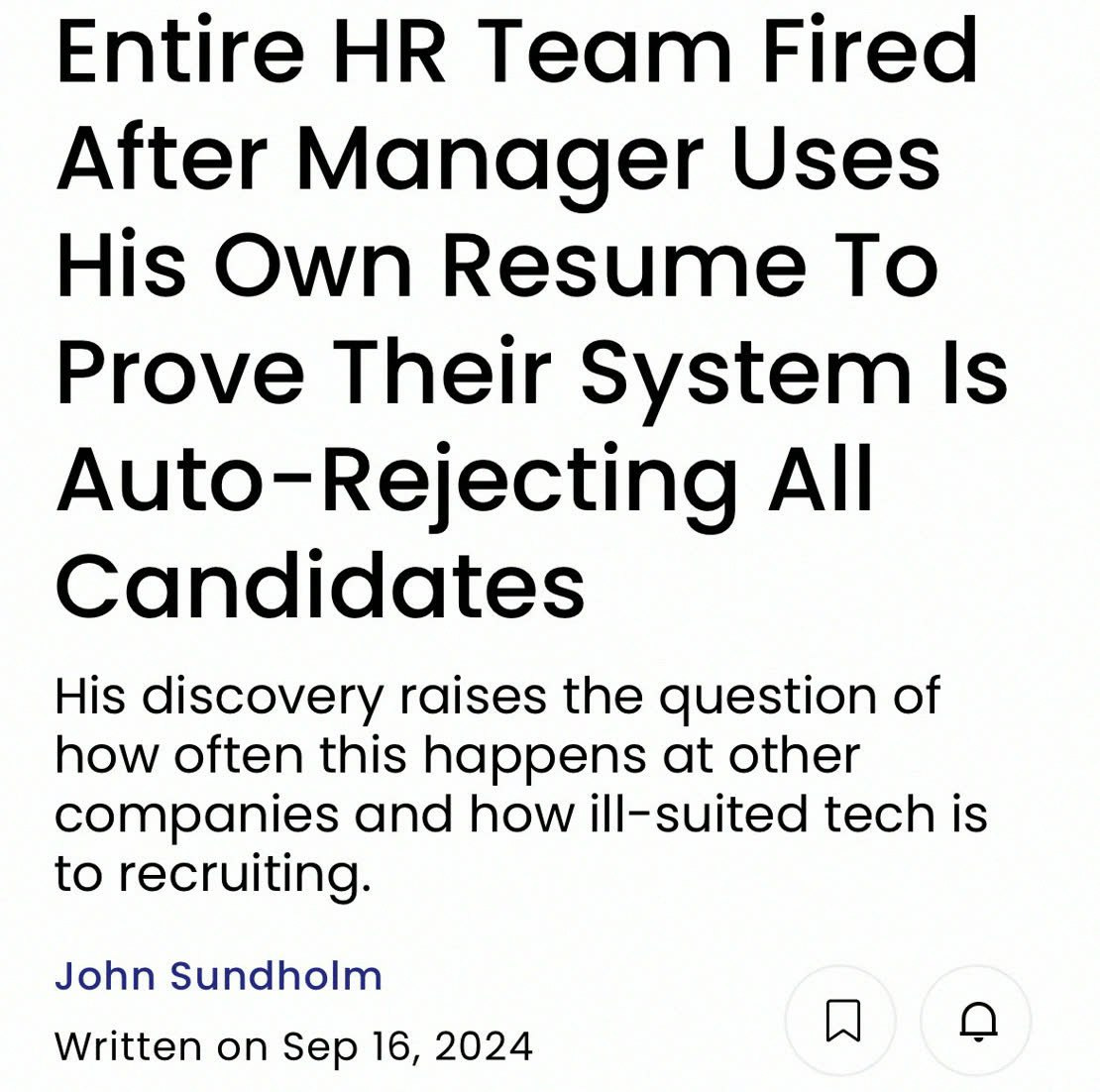

The only clear mistake Nikita is making here is underestimating AI.

Nikita Bier: Over the next four years, the only thing that will have a greater economic impact than AI will be the financialization of everything, the effective legalization of gambling, and the elimination of all securities laws.

Black Einstein: I’d bet money on this.

Nikita Bier: And now you can.

What the anti-capitalists usually sound like, except more self-aware.

Grimes: I’m not a communist – I’m probably a capitalist but I think the incentives in capitalism are bad, and the dollar shud be backed by something more meaningful – like trees. I know that’s insane and likely impossible but I’m an artist so my job is to say things like this.

It’s an especially funny example to those who know their Douglas Adams. Which, given that Grimes had a child with Elon Musk, presumably includes her.

Not while I’m alive, anyway.

I’m in.

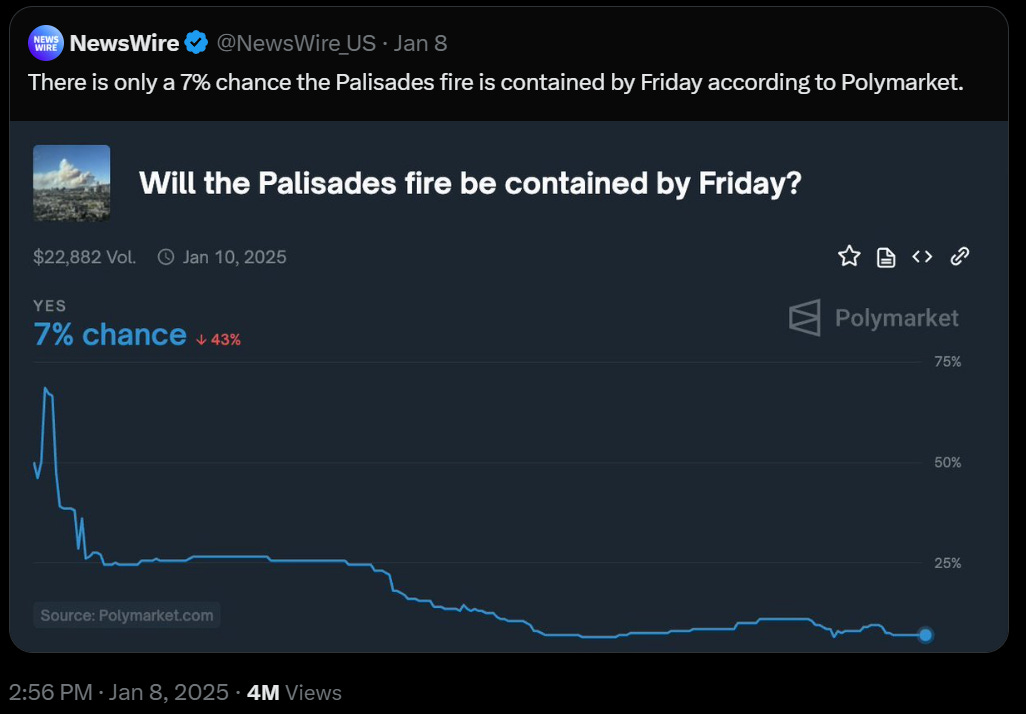

Armand Domalewski: movie about a team of degenerate gamblers who single handedly contain a massive fire in order to win a huge score on Polymarket.

But what am I in for?

(For those who don’t know, this is from the NYC subway when loading a MetroCard.)