I got suckered into paying attention to multiple non-AI political stories this month: The shooting of the messenger, in violation of the most sacred principles, via firing the head of the USA’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Online Safety Bill in the UK.

As a reminder, feel no obligation whatsoever to engage with either of these.

There are tons of other things worth paying attention to that are not that.

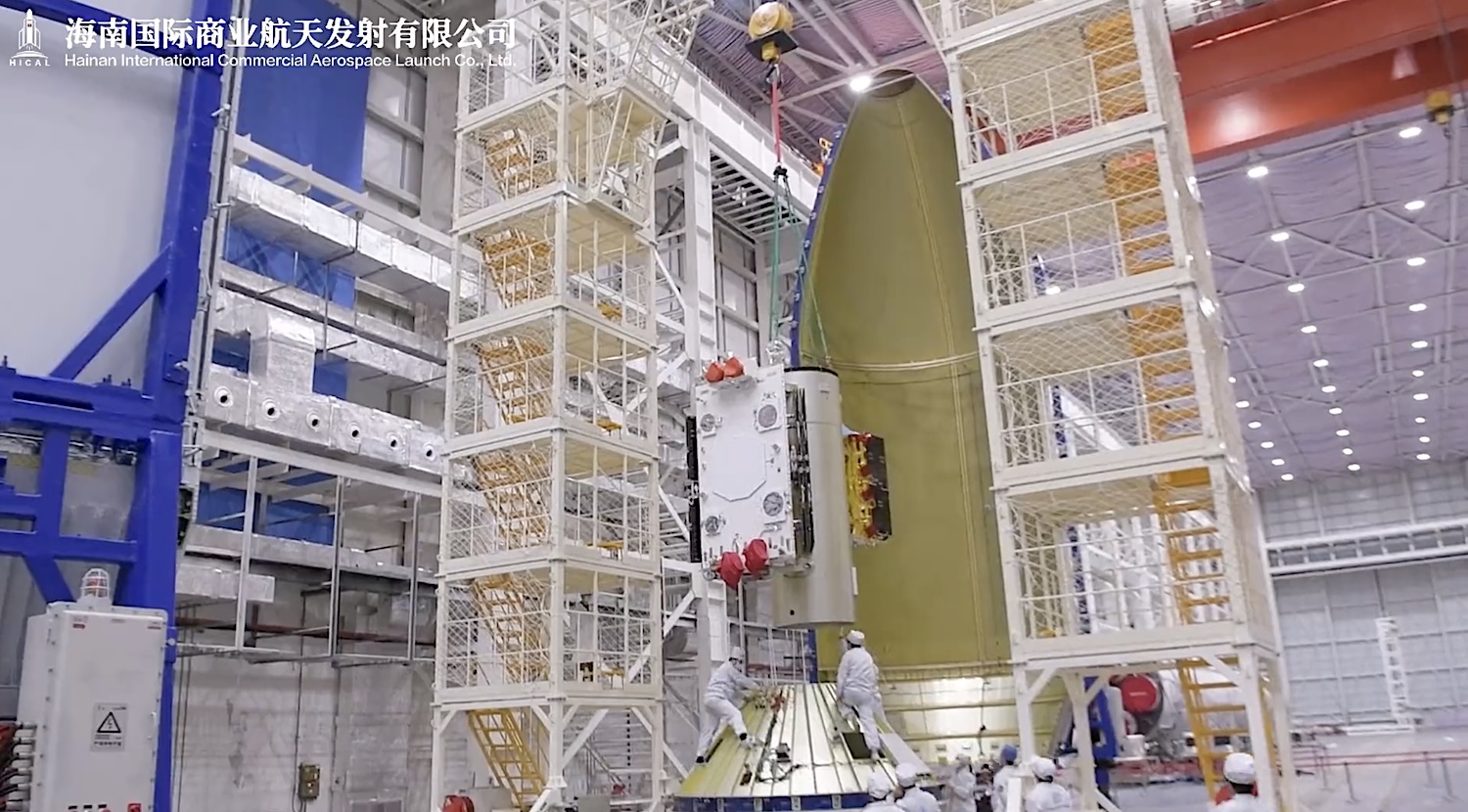

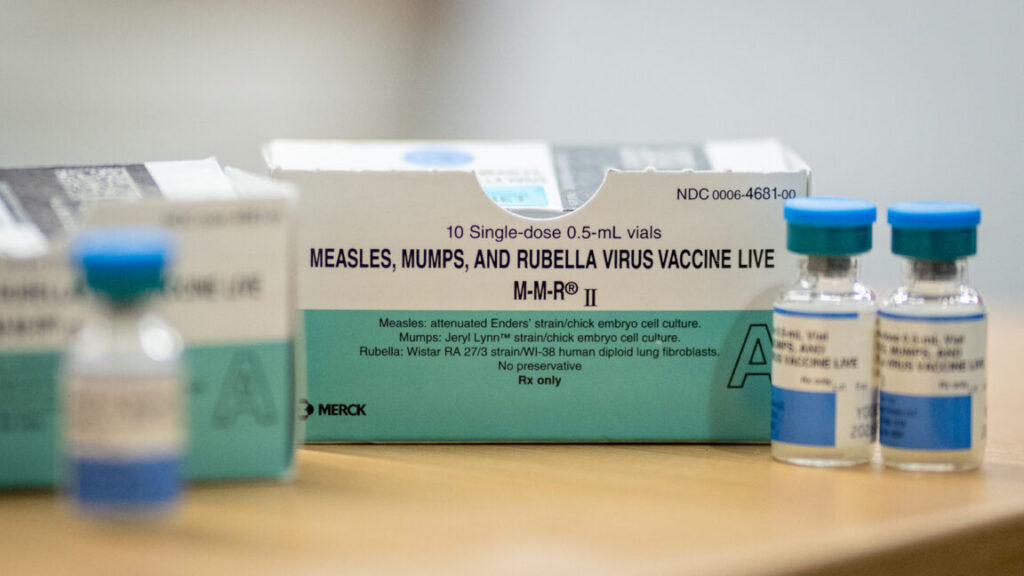

I realize philanthropy has been handed quite a few sinking ships lately, but if you exclude AI there is one crisis I would prioritize above the rest, which is mRNA.

Which is: We have entered the War on Cancer, future pandemics and other diseases on the side of cancer and future pandemics and those other diseases, because we decided to hand this power over to RFK Jr.

As Rick Bright puts it in the New York Times, America Is Abandoning One of the Greatest Medical Breakthroughs. We don’t have to let that happen.

Albert Pinto: Holy moly trump killed Moderna in US!!

“The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) today announced the beginning of a coordinated wind-down of its mRNA vaccine development activities….”

“The projects — 22 of them — are being led by some of the nation’s leading pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Moderna to prevent flu, COVID-19 and H5N1 infections.”

Jesse Jenkins: Project Warpspeed was probably the most consequential and unqualified success of Trump’s first term, and mRNA vaccines one of the most exciting medical advances of the 21st century. But this time, Trump 2.0’s anti-vax HHS Secretary (Kennedy) is cancelling all federal funding for 22 active mRNA development initiatives. There just aren’t enough facepalm gifs for all this stupidity.

Alc Stapp: mRNA technology is miraculous and has so much potential.

This is such a massive own goal.

Thorne: We’re fairly close to being able to very effectively treat cancer with mRNA, and this will be a huge setback

To be blunt: people you care about will die of cancer because of this decision

It’s deeply delusional to think that just because this announcement is about respiratory viruses, it won’t greatly impact mRNA vaccine tech as a whole.

mRNA companies get way less funding now and have strong signals that other mRNA vaccines might face regulatory hurdles.

Also, a lot of people are responding as if I’m saying such a tech cannot possibly be developed without public funding. No, I said it was a huge setback. And that means people who could’ve been cured will die waiting for it.

A huge portion of optimism about new medical technology, and even about the future in general discounting AI, is mRNA vaccine development. They’re trying to kill it.

Private investment can and must come in and over. The funding gap here is only $500 million. Certainly some combination of billionaires (and perhaps others) should step up and their make grants or invest as needed to fix it.

The cost-benefit ratio here is absolutely absurd. When we think of the futures that aren’t transformed by AI, mRNA is one of the technologies giving us the most hope. If those who heave the means do not pick up the slack here, flat out.

This comes on the heels of various forms of amazing news about mRNA, such as this:

Kepecs Labs: Huge cancer breakthrough! mRNA vaccine (similar to COVID vaccine tech) shows stunning results against pancreatic cancer! 75% of responsive patients STILL cancer-free at 3 yr, normally 80% recur. Could revolutionize treatment for one of deadliest cancers! Funded in part by @NIH

The thread is full of the kinds of graphs you see when a treatment works really well.

A. Do responders still have better outcome?

Left = 1.5 yr follow-up

Right = 3.2 yr follow-up

Yes! 👇🏽

16. TAKE HOME

In #PDAC, RNA NA vaccines make CD8 T cells of

– multiyear longevity

– substantial magnitude

– durable effector function

whose presence

– correlates with delayed recurrence at 3-yr follow-up

The worries are politics and game theory.

In terms of game theory, if we step in and save this situation, did we effectively let the government steal $500 million? Won’t they then have every reason to do it again and target the best programs? Won’t this willingness to fund (acasually) be the reason this got cut?

My answer here is no, because this cut was intended not to steal the money but to stop the research. The people who are cheering this have bought into their own paranoia or perverse incentives so much that they actually want mRNA dead. In such cases, it is relatively safe to step up, although it does carry some risk of giving people ideas.

In other situations, the dynamics are different. Either the motivation was indeed to save or steal money, getting others to pick up the slack. Or it was to use a wrecking ball to kill a wide variety of things, knowing the best ones would then gets saved. Then you have to look at these questions a lot more carefully.

The politics means both that the administration might then use other means to stop mRNA or at least not be helpful, or that this might mark one as an opponent of the administration.

I would not worry much about the administration not playing further ball. This is a long term fight, and also we have reports Trump himself is not thrilled about the cuts. It is also quite a lot harder to turn down the life-saving medicine when the time comes than it is to deny the initial funding. The pressure would be immense, and also there are places besides America to start deployment if you need to do that for a bit.

I also don’t worry too much about this alienating the Trump administration. You’re investing in America, Trump was reportedly not thrilled about the cuts, and he definitely isn’t a true believer on this like he is on tariffs. He knows that being against mRNA is about placating crazy people, so if it happens without him, that is fine. That assumes, of course, that you are worried about this dynamic in the first place. Some people very much aren’t.

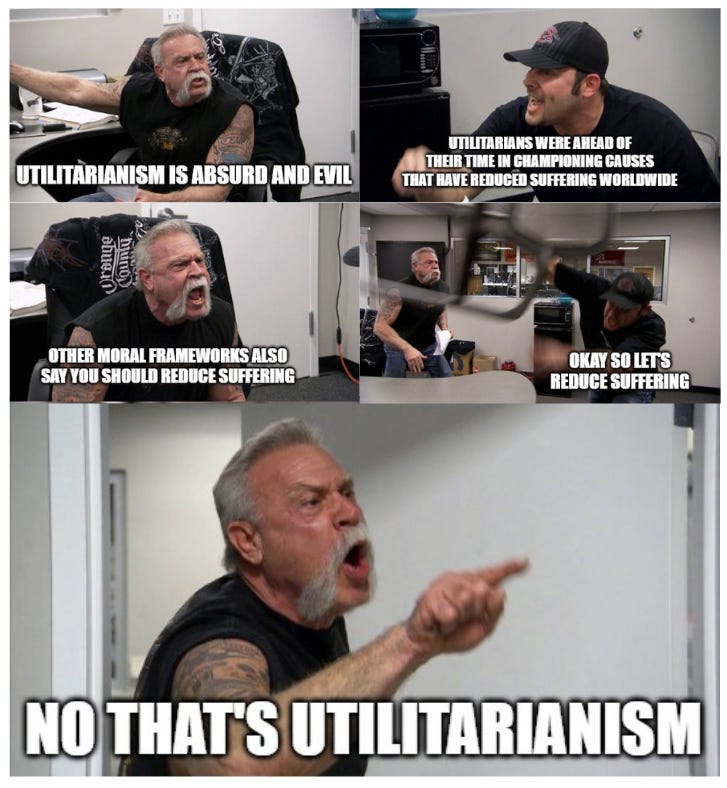

This pattern is common. I think centralizing suffering is a critical mistake, so you can substitute various things for ‘utilitarianism’ and also various things for ‘suffering.’

Although also, yes, at reasonable prices, and while factoring in other things we also care about, we should reduce suffering.

Also, yes, this is about how well most people deal with hypotheticals.

This is also a central common pattern, and the difference that matters.

Henry Shevin: Many years ago, I went to two animal welfare events with very different types of philosophers.

The conclusion of the first was “we need to have another bigger conference next year, with animals present.”

The conclusion of the second was “we need to fund in-ovo chicken sexing.”

I would not go to either conference. But, if you did go to one such conference, you would want it to be that second one.

I will note that there is already lots of talk about making the new in-ovo chicken sexing technology mandatory, starting in Europe. There will always, always be a push to make such things mandatory.

Some more making fun of how awful Cate Metz is and how much he got everything wrong yet again:

Leila Clark: on the lighthaven drama, from a friend:

A true statement:

Roon: Public goods are often expensive gifts to yourself scaled up.

David Manheim: Yes – and this is a reason that wealth inequality often leads to public benefit.

The cheapest way for wealthy firms to have educated workers is public education, and the cheapest way for the rich to reduce climate risk is fixing emissions globally, etc.

This is also why I refer to the ‘chasm of personal utility.’

Once you hit fyou money, there is remarkably little that additional money buys on a personal level. Marginal returns drop dramatically. It takes quite a lot of additional money to get remarkably little benefit. The things people buy for themselves that actually get expensive, like boats and lavish private parties, really aren’t that great.

If you actually want your life to get better, the only way to do so becomes improving the world, since you and those you care about have to live in it. Hence, public goods.

As a toy example, as a gamer, I could basically buy whatever I want and not bat an eye, unless I wanted things like Vintage Magic decks, and even that has an upper bound. So at that point, if I want better gaming, what do I have to do? Commission games.

Elizabeth von Nostrand: Lots of people want my job. No one wants the part where I spent five years doing this job for free.

Ben Landau-Taylor: Most of my friends with weird jobs could say the same.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Word.

Nefarious Jobs will, for a remarkably small fee that usually is only four figures, go out and ruin someone’s life, in ways that they say are technically legal, with the ‘Total Annihilation’ package only costing $10k. In addition to the other obvious reasons it is terrible, one strong reason not to do this is that it can be done back to you.

Reservations at DC restaurants plunge 31% compared to 2024 in the wake of the police takeover.

The trucking industry reports it is experiencing the dreaded double whammy, intense labor shortages combined with declining wages. Um, yes, you did read that correctly.

RIP Hulk Hogan, a lawyer from Bollea v. Gawker offers a retrospective on the case that took Gawker down.

Reminder, once again: When people tell you who they are, believe them. Kelsey Piper is latest to confirm that people who identify themselves as evil, or with Hitler or as a fascist or a Nazi, will universally prove to indeed suck immensely.

It appears to not be a strawman that some disability activists oppose treating disability via gene editing because this would mean there would be fewer disabled people, which would weaken their ability to exert political pressure.

Rebekah Westenra: Begging the average disabled person to understand that it’s not about you. You will never ever get access to this kind of tech. This will never be a cure for YOU. This is about eliminating disability from the upper class which will reduce support & resources directed towards YOU.

She is of course directly incorrect, developing cures for the rich is how you develop the technology, after which it leads to cures for everyone else, but even if she were somehow correct, consider what don’t even count as the implications, just the outright telling people if they are rich then it is good they are disabled, my lord.

Oh, and then the follow-up is, maybe curing your disability would be bad, yo, and if you disagree with this than you’re not really a disabled person so you have no right to talk, there are those who can make this up yet I remain not one of them.

Also begging people to understand the differences between various disorders and to think about what makes you YOU and if your disorder can be completely separated from that then maybe just shut the hell up for now.

Those corporate ‘icebreaker’ and ‘team building’ events? Yeah, they are pretty important to your success at your job. You need to go all out with faking sincerity.

Simon Fruit: One of my favorite employment phenomenons is this retarded idea that if you do your job very well but don’t participate in stupid, time-consuming, and useless ice breakers then you’re not a “team player” because you made Brenda feel bad that you didn’t care for her weekend.

Andrew Rettek: I got fired for this once.

Patrick B: Three phrases to remember: Oh wow crazy. That’s amazing. Oh no he didn’t.

This is effectively a large reason to seek out coworkers you like hanging out with, since you’re going to be forced to do that if you want to succeed.

I never had a problem with such work exercises, because the offices I did join for any length of time – Jane Street and Wizards of the Coast – selected for people I would have been happy hanging out with anyway.

I did however kind of get fired as a student at a Dojo for this. For a while I would go to class twice a week and had moved up one rank. I was informed by Sensei that as I kept going, they expected me to participate more in the community. I found the other students to be nice people, I didn’t at all mind training with them and making small talk, but burning evenings socializing? Oh, hell no. That was essentially that.

Well, this seems not awesome:

The farther you go downthread the worse it gets.

It seems in Cairo (and presumably many other places) Uber drivers flat out ignore the fare they accept and then you have to haggle. Like James here I absolutely cannot stand small stakes haggling. Transaction costs are very high and it makes sense that the Anglosphere has long had a big advantage everywhere it doesn’t haggle, but struggles on housing which is the one place we still do it and have to hire people to advise us on optimal haggling techniques.

Whisper networks are terrible, but what is the alternative? Ideally actual fact finding, but that is expensive. You cannot play that card so often, and indeed you need a whisper network or something similar to know when to invest in fact finding. Next up would be creating common knowledge and only saying things in the open, which also has obvious limitations. If nothing else, it means that if you can make the victim or witness not want to come forward, in one of any number of ways, you get away with it, and it is not obvious how to go from ‘whisper networks are bad’ to preventing one from spontaneously arising unless you have an effective alternative mechanism. Also, if you cannot say anything negative about anyone without telling them directly, that leads to heavily biased information and also various games where silence starts to be highly meaningful. I don’t see any good solutions?

Wes: Whisper networks are bad, for obvious reasons.

Xenia: unfortunately also good for obvious reasons.

Wes: Alas. The bad parts tend to eat the good parts.

Sparr: In my intentional community organizing efforts, I have tried and failed a few times to establish this rule/norm:

Say nothing negative about someone behind their back that you don’t say to their face, unless it should get them kicked out of the house.

Wes: Why does it fail?

Sparr: People refuse to honor/follow it. If I could find a core group of 3-5 people who would adopt this norm, new people could be acculturated. But I have never found that core group.

Recommended: Cate Hall tells us 50 things she thinks she knows. The list is as excellent as everyone says it is. Many of these are exceptionally valuable if you don’t know them or needed a reminder. A number of them are in my opinion false, actively unhelpful or both, but that keeps you on your toes and a list where all 50 were true and useful would not be as interesting. Like her I could probably write a post about most of these if I wanted to (especially the one I think are wrong).

Cate Hall also offers praise for quitting, especially quitting when you realize that you don’t want the results of walking down a long term path. Some people of course need to reverse this advice.

Recommended: The Inkhaven Residency at Lighthaven in Berkeley, happening November 2025. If you attend you will write 30 blog posts, one per day, or leave, with advice and mentorship from Scott Alexander, Scott Aaronson, Gwern and more. Cost to attend is $2,000, housing is available as low as $1,500 ($2,500 for a private one).

(I do not currently have a plan to make an appearance myself, I only have so many trips in me per year, but certainly there is some chance I will choose to do so.)

Zohar Atkins presents a new Library of Alexandria, 4000+ great books combined with an AI tutor, called of course Virgil, to converse with.

I am doing my best to avoid commenting on politics. As usual my lack of comment on other fronts should not be taken to mean I lack strong opinions on them. Yet sometimes, things reach a point where I cannot fail to point them out.

If you are looking to avoid such things, I have split out this section, so you can skip it.

This month, that applies to the following two sections as well.

Because this is the realm of things like this:

Tetraspace: Reading another thread of people replying to “this law should be changed” with “but it’s the law” and being thankful that democracy achieving good outcomes doesn’t rely on people understanding policy details.

Replacing the H-1B visa lottery with a system based on ‘seniority or salary’ predicted to raise the program’s economic value by 88%. I would worry that ‘seniority’ is too easy to fake, so I would go with salary as much as possible. It is also argued that this would prevent the driving down of wages for native workers. Even better would, of course, be to straight up auction off the visas themselves, or set a market clearing price (ideally with much higher supply, perhaps the level that maximizes revenue), which is the obvious solution.

🚨 BREAKING: A bill to ban politicians from trading stocks is getting pushback from the White House, per Axios.

The pushback seemed to be they did not like that it applied to the President and Vice President. I can’t imagine why. I only report the news.

The good news first. The UK backed down from the encryption standoff with Apple amid US pressure.

Then they went and did all the other stuff they did this month. Oh no.

The free speech situation in the UK seems about to get somehow even worse on multiple fronts at once?

The situation has reached the point where if I lived in the UK, I would feel it necessary to leave, because I would otherwise not feel safe doing my job.

Dominic Green: On the night of Wednesday, July 16, the Labour government’s Employment Rights Bill passed its second reading in the House of Lords.

If the bill goes into law in its current form—and there is not much to stop it now—Britons can be prosecuted for a remark that a worker in a public space overhears and finds insulting.

The law will apply to pubs, clubs, restaurants, soccer grounds, and all the other places where the country gathers and, all too frequently, ridicules one another.

Meanwhile an ‘elite police squad’ is monitoring anti-migrant posts on social media.

Oh, and on the first day of the ‘Online Safety Act’ they were already on the verge of shutting down Wikipedia. Could there be any clearer sign things are extremely bad?

Evolve Politics: Wikipedia is currently in a legal battle with the UK government to try and stop the platform being censored in the UK – or even completely blocked – thanks to the Online Safety Act.

Under the new law, the UK media regulator Ofcom is poised to label Wikipedia as a “Category 1” platform.

This would impose the strictest content rules possible – such as:

– age verification for users

– identity verification for contributors

– censorship of ‘harmful’ topics.

Wikipedia has already stated they will not implement any of these rules, arguing they would be forced to censor crucial facts, and potentially expose their volunteer contributors to real-world harm – such as political harassment, or worse – purely for documenting the truth.

In addition, Wikipedia says that bad actors could easily abuse the new laws – by filing fake complaints or exploiting vague “harm” rules to force them into entirely removing articles that people – or the UK government/corporations – simply disagree with.

Wikipedia’s legal case was heard at the Royal Court of Justice on July 22-23, and a ruling is expected within a month or so. However, if their legal arguments are rejected and they refuse to implement Category 1 rules, the UK government could block access to Wikipedia entirely.

It is a great relief to confirm that Wikipedia is not going to give in here, especially on censorship of ‘harmful’ topics even for adult users. They have since lost their court case.

Chris Middleton lays out what the Online Safety Act does in general.

Chris Middleton: It creates a new “duty of care” on all online services to police user content. This means:

✅ Platforms must proactively detect and remove “illegal” and “harmful” content.

✅ Age verification to block under-18s from adult material.

✅ Private messaging apps must scan messages for banned content.

WhatsApp and Signal warn this poses an unprecedented threat to encryption and privacy.

Age checks and the death of anonymity:

Any site with adult content must now implement “highly effective” age verification. That means:

📸 Face scans

📅 Government IDs

💳 Credit card checks

This applies far beyond just porn to any user-generated platform. The law covers any site that allows users to share or interact. That includes forums, messaging apps, cloud services, open-source platforms, even Wikipedia.

Proton VPN: Just a few minutes after the Online Safety Act went into effect last night, Proton VPN signups originating in the UK surged by more than 1,400%.

Unlike previous surges, this one is sustained, and is significantly higher than when France lost access to adult content.

Wint (August 28, 2013): lets set some realistic goals here : jokes banned by 2016. sex banned by 2020. a cop in every household by 2025

What kind of things are being censored, in addition to Spotify, which is also threatening that it might have to delete your account?

Saruei: I can’t believe Spotify now requires age verification. Today it’s music, tomorrow it could be books, films, or even news articles. It’s the first step into a dystopian reality we’ve seen in movies, where access to culture is gated by surveillance and the illusion of security.

Calgie: Your Spotify account is getting deleted unless you do age verification.

Adam Wren: For everyone that was saying “it’s just to stop kids watching porn” very first day of the restrictions it’s been used to censor “violence” which in this case means police arresting people at protests, well done. The very first day. Not even a ‘slippery slope’ at this point, more of a wet cliff.

Benjamin Jones: If you have a standard X account in the UK – presumably the vast majority of British users – you cannot see any protest footage that contains any violence tonight. Because of the Online Safety Act. A relative in America sent me this screenshot of one blocked post.

Matvey: It’s frankly disgusting that the Online Safety Act is being hidden behind the pretence of ‘child protection’ when it’s already being used to hide political content from non-age-verified uses, and next year will be able to take IP from tech companies at no notice.

Draconian.

It was a bold move, Cotton, to go directly after Wikipedia and coverage of police and protests and testimony before Parliament on day one. They did not want there to be any illusions what their true target was.

Charles: I just got asked to submit ID to view a Reddit wine forum.

Immediately thought “I’ve got to get out of this country (the UK)” and bought a VPN subscription.

Now I’m digitally in the much more free nation of “checks notes” Belgium.

But the impulse to physically get out remains. This is not a place that feels hopeful or optimistic or like it’s going to change for the better soon.

Would I call this new UK a ‘police state’? Well, it is a place where they censor and potentially jail you if you criticize the police. I mean, if you’re censoring Wikipedia and you’re blocking videos of police arresting protesters, I realize Wikipedia does do some rather nasty politically motivated things like whitewash Mao as if it was defending him in court, but what more is there to say?

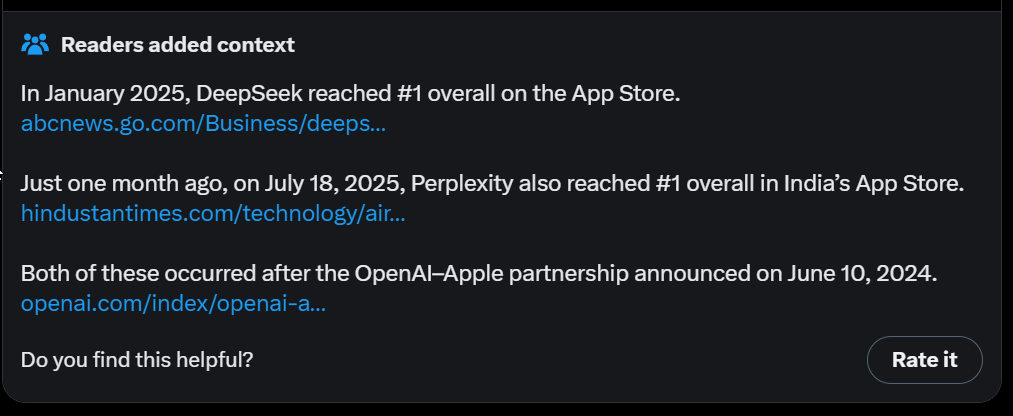

The community note is incorrect. This very obviously was exactly what the act was for. I’m not a pure ‘the purpose of a system is what it does’ person, but yes very obviously the purpose of this system is to censor speech authorities dislike.

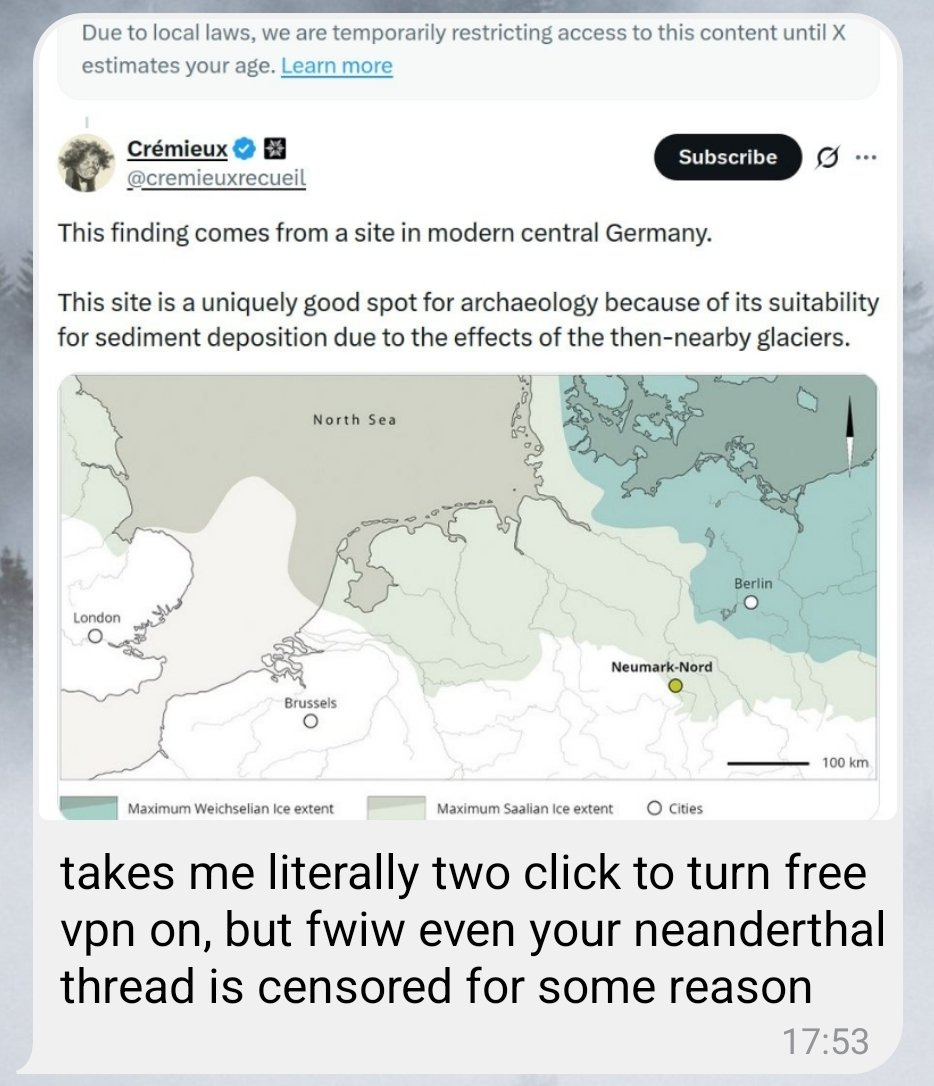

Cremieux: The Online Safety Act censored one of my posts on lactose intolerance. It censored another where I mentioned donkeys, and my friend can’t see one of my posts on Neanderthals processing fat. If you support the Online Safety Act, you are an imbecile.

Nigel Farage and the Reform Party would get rid of the Online Safety Act, or as the Labour Party calls it, ‘scrap vital protections for young people online, and recklessly open the floodgates to kids being exposed to extreme digital content,’ the same way they were so exposed before and are so exposed in other countries, and thus he is ‘not serious.’ They also say you are ‘on the side of the predators’ while, censoring official discussions about investigation of actual predators.

Many such cases.

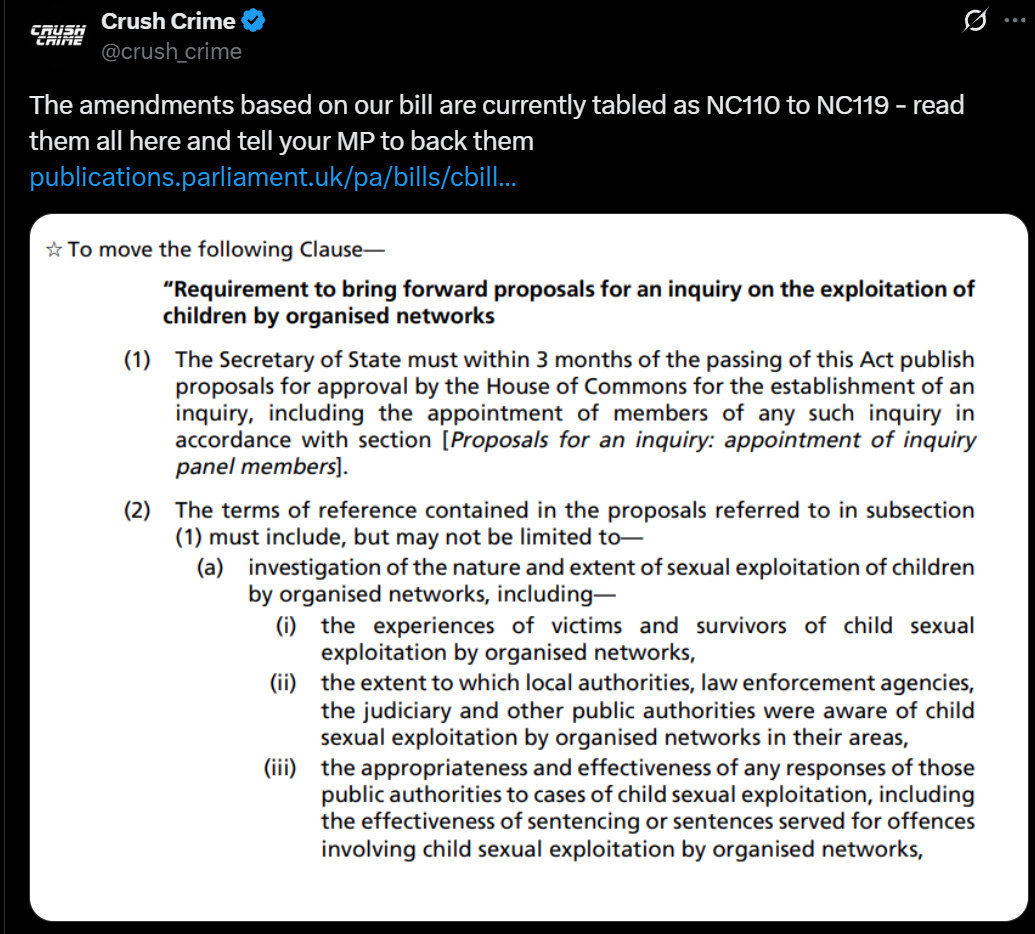

Crush Crime: Our post with a screenshot of a House of Commons amendment, setting terms of reference for an inquiry into the grooming gangs cover-up, has been censored by the Online Safety Act. The state must spend less time policing speech and more time catching rapists and thieves.

Here is that post:

Sam Dumitriu: “Nigel Farage would give teenagers access to material on drinking cider, owning hamsters, and speeches from Conservative Members of Parliament. He is simply not serious.”

Charles Haywood compares the situation to that in Eastern Europe in 1989, as in it has become clear that the government will not respond to the public’s views except by trying to censor the public, including censoring statements that the majority agrees with and statements about police conduct, political opinions and the coordination of protests, now including on social media, in pubs and in private chats.

It can always get worse. Australia is going to make you prove your identity in order to access search engines as in Google and Bing, and they want to ban YouTube for kids under 16 as part of their social media ban, WTAF.

The UK is seeking to pass a law enabling the issuance of ‘respect orders’ to prevent someone from engaging in ‘anti-social behavior’ that can ‘prohibit the respondent from doing anything described in the order’ or ‘require the respondent to do anything described in the order.’ The court can simply order you to do or not do actual anything? So I suppose they spell respect T-Y-R-A-N-N-Y.

Isaac King: “The text of my new bill, the End All Bad Things Act, is as follows:

I can do whatever I want.

This will allow me to make people stop doing bad things. Thus if you oppose this bill, you are in favor of bad things.”

Then again, what did we expect from a country that censored the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles?

R Street: The U.K.’s Office of Communications (Ofcom) explains in detail what each category of prohibited content includes—even “[c]ontent which realistically depicts serious violence against a fictional creature.”

Such a definition would not only prohibit minors from accessing historical and newsworthy content about wars—but many episodes of SpongeBob (if posted to social media), including but not limited to “No Weenies Allowed.”

Meanwhile, YouTube is now going to ‘use AI’ to ‘interpret a variety of signals,’ including account longevity and which types of videos a user is searching for and watching, to ‘estimate’ whether a user is 18 and thus age restrictions must be imposed.

Klint Izwudd: Isn’t it fucking amazing how worldwide all of these incredibly sophisticated censorship measures are literally appearing in the last week.

The direction of this move is ambiguous. If the previous regime was that everyone was treated as a minor until proven otherwise, and now you have a second way to get the regime to stop doing that, and how minors are treated does not change, then This Is Good, Actually. Alas, this likely goes hand in hand with worse treatment of minors. From this article, it sounds like this will effectively mean an expansion of restrictions.

Also note that the actual changes listed are (they use the word ‘including’):

-

Disabling personalized advertising

-

Turning on digital wellbeing tools

-

Adding safeguards to recommendations, including limiting repetitive views of some kinds of content

All of those seem like they could be straightforward upgrades? Can I choose to turn on those features?

What they of course fail to mention is that the main change is age restricting videos. I do notice that I have an alt Google account, I definitely did not provide Google my ID there, and when I use YouTube on it I have yet to run into age restrictions on videos.

A fun note is, if you were trying to ‘look like an adult,’ what would you do? You would among other things try to make your consumption as age inappropriate as possible?

I would very much like to see this handed as follows by the tech companies:

Arthur B: If Meta and Google had the courage to entirely drop service for the UK, the government would fold in two weeks and repeal the OFA. The EU, Australia, etc would start to backtrack. Two weeks is all it takes, it could be done.

Wikipedia has the right idea. By all means sue, but make it clear that if push comes to shove you will simply cut the country off. Even if the governments held firm, fine, so be it, let everyone use a VPN.

The traditional way such stories end, when they don’t end in revolution, is this:

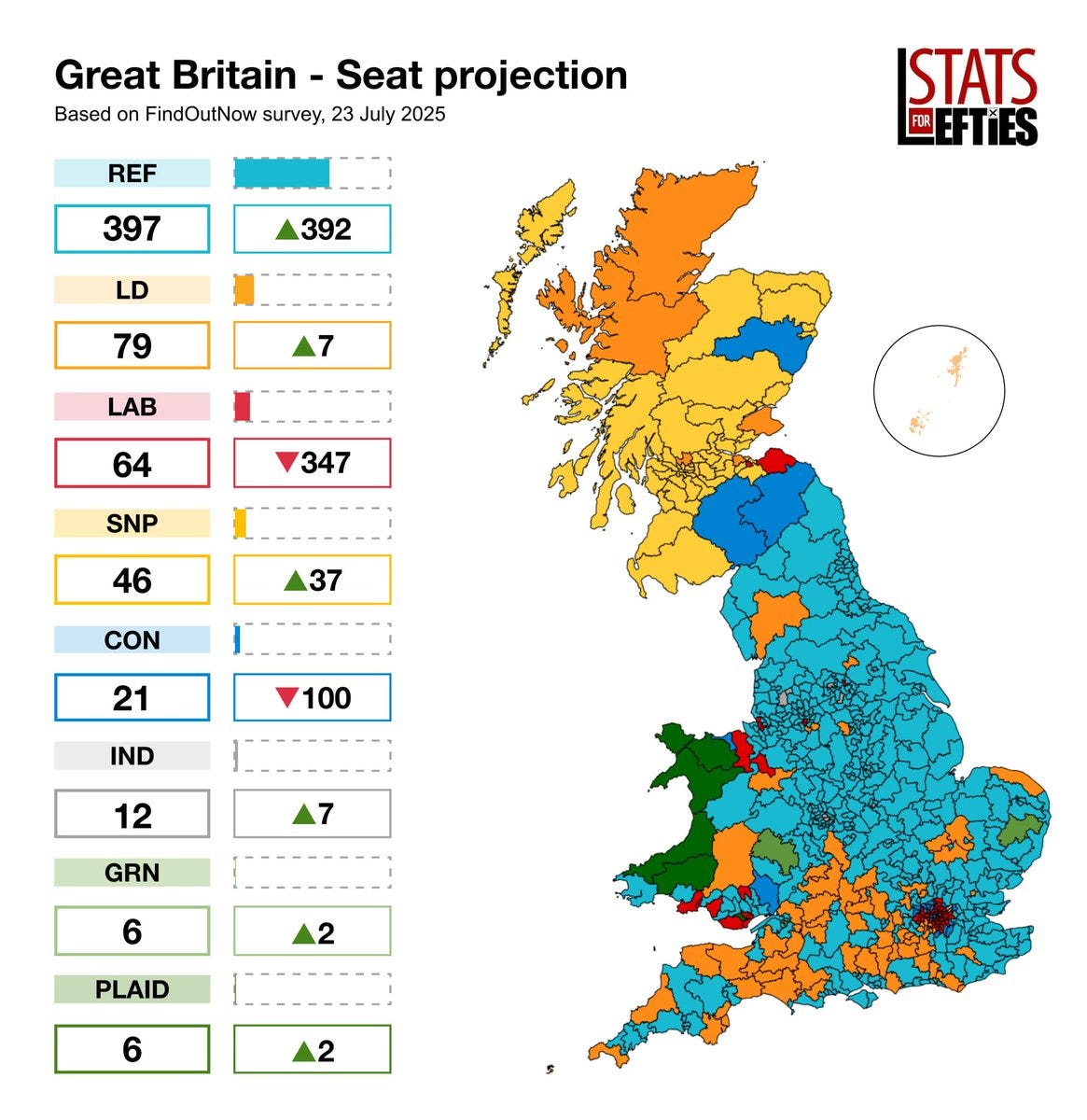

Devon: This is what current polling looks like when you don’t include LeftParty_Final. I’m sorry but anyone making the “you’re gonna split the vote and let Farage in” argument has their head in the sand and can be safely and derisively ignored.

In particular I would not have simultaneously severely censored the internet for 16-and-17 year olds and also given them the vote. That’s just me.

Here’s the strongest argument I’ve seen yet that actually Brexit was a mistake. You might need to get away from the EU but that doesn’t help if you then act even worse:

Alex Tabarrok: The British would never have tolerated this if it came from Brussels and EU bureaucrats.

Once regulation was seen as self-imposed, the floodgates opened.

Mr. Obvious: BREAKING: Zoomers cannot adjust their Nvidia graphics cards settings on their gaming PCs anymore because they aren’t 18 thanks to the Online Safety Act.

To be fair, if you can’t get a VPN working then you shouldn’t be using Nvidia apps.

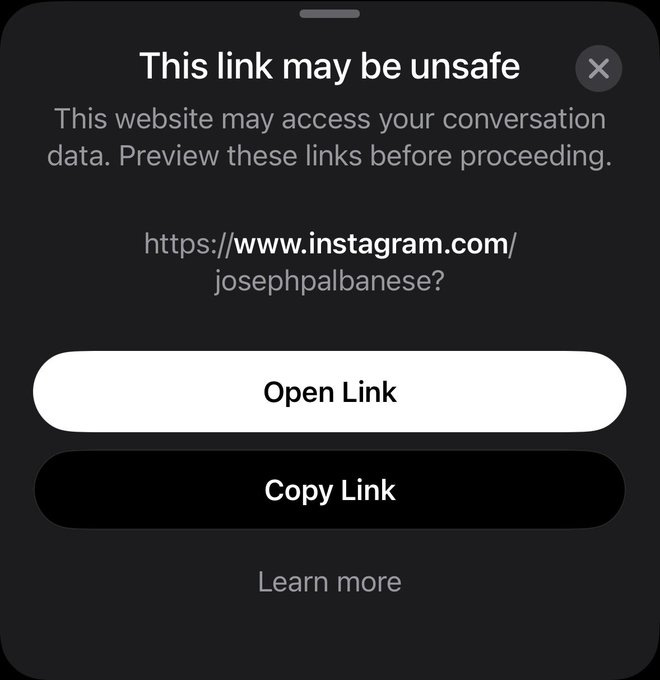

Michi: UK App Store charts be like

Guess who is also downloading those apps, also billing the public for them?

Freddie New: Peter Kyle suggesting that using a VPN will put children at risk (a laughably luddite suggestion, as he probably uses one himself every time he works from home)… At the same time that Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds (famously confused as to whether he is or is not a lawyer) is billing his use of a VPN to YOU, the taxpayer.

Why doesn’t Jonathan Reynolds just verify his age instead?

I honestly wish someone was making this all up.

Ultimately, yes, this is the choice and the choice is #1:

Jeremy Kauffman: Most people won’t state this so bluntly, but if the choices are:

-

kids sometimes access pornography on the internet

-

a federal ID system to access the internet

Then #1 is the better choice.

Well, actually the #2 choice is you have a federal ID system and the kids access the porn anyway, but it was never about the porn. The porn is an excuse.

Misha: The dangers to children of potentially seeing porn are trivial compared to the benefits of being able to freely access the internet

Kelsey Piper: And the most overwrought hysterical “this is the first step towards requiring government ID before you read or talk online at all” predictions have been borne out in full so swiftly that I don’t see how you can possibly feel certain it won’t happen here.

like, I’m sorry! I too really hate how hard it is to give kids a healthy online experience! and I will oppose every effort to enshrine age verification in either the law or in company policy on any level for any reason.

Matthew Lesh: The Online Safety Act debate was a lonely place for free speech advocates. Anyone who dared to question the law was treated as a child-hating pariah. Yet as key provisions have come into force our warnings have proven eerily accurate.

Institute of Economic Affairs: There was shock that anyone might dare to question a law designed to ‘protect children.’

In a separate meeting with a senior Ofcom official responsible for implementing the law, I was politely assured that excessive implementation is never a problem with regulation, leaving me utterly dumbfounded.

If those implementing a law tell you ‘excessive implementation is never a problem with regulation’ and you let them continue implementing, you know what you will get.

There was a period where we were constantly told that those concerned about AI killing everyone would impose dystopian authoritarian nightmare surveillance states because we wanted to impose some restrictions on who could train or distribute future frontier AI models potentially smarter than humans.

Instead, things far worse for freedom than anyone was talking about are being imposed because otherwise ‘you are not serious about protecting children from predators’ or what not, and being used to suppress dissent and also settings on Nvidia cards on day one. Somehow most of the same voices are being a lot less loud about it.

They are even going after good old free speech Americans like 4Chan, whose response letter correctly said they would fight any and all attempts and calling upon the State Department to step up its game, but seemed altogether too polite. Let 4Chan be 4Chan, at least this one time.

Also, frankly, go ahead, go after 4Chan and see what happens. It’ll be fun.

Then they went after Twitter for censoring in the UK too much, because it made the UK government look bad.

Preston Byrne: I was asked to comment on a story today about this. Apparently Ofcom wants to punish X for “over-censoring” user content, making the UK government look bad. In their view, X violates the Online Safety Act by over-complying.

“If Ofcom goes after X, I hope Elon kicks their ass.”

Also, I’m not sure what Ofcom is smoking, but there is no rule in English law which requires a website to platform lawful speech.

Maybe the UK is taking an expansive view of Article 10, but that’s just more evidence that Article 10 is vague and crap and should be abolished.

Forever Scept: TRANSLATION: You were supposed to censor without them knowing.

Preston Byrne: Right. “You’re supposed to censor only what we want you to censor, and we aren’t going to tell you what we want you to censor until you get an enforcement notice for censoring incorrectly.” Yeah, no. Absolutely not.

Patrick McKenzie: This is a recipe for censorship by “Come on, you know what we want.” followed by zero point zero democratic accountability. “All independent decisions of firms made for commercial reasons; we have no orders.”

We have seen this movie before, depressingly frequently.

America’s State Department has spoken up at least a little.

Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL): The UK’s Online Safety Act undermines the right to free expression by imposing censorship on vague grounds. Suppression of criticism of illegal immigration or the criminal justice system is completely unacceptable in a free society.

These laws will also create immense pressure on American companies to kowtow to the censors. Foreign laws must not undermine the right to freedom of expression of Americans.

There was then an escalation.

Preston Byrne: The US State Department’s report specifically notes the UK/Ofcom has been targeting Americans with no corporate presence in the UK for censorship.

I am proud to have supplied the US government with all relevant documentation on this point.

Meanwhile over in the EU they mandate TVs to lock the brightness at 30%-50% for sustainability reasons, as in ‘eco mode,’ and you have to dig deep into settings to fix it. But that’s nothing compared to what is coming, you are to hold their beer or wine.

Marko Jukic: The EU intends to automatically scan every private message sent over a phone, including encrypted ones, for “child abuse material” by this October. No prizes for guessing what else they will scan for in a few more months or years. Final death of free speech and free internet.

If you have one rule, this is it. Also, if you must shoot the messenger, do not shout ‘THIS IS SPARTA’ like it is a good thing that you are doing so.

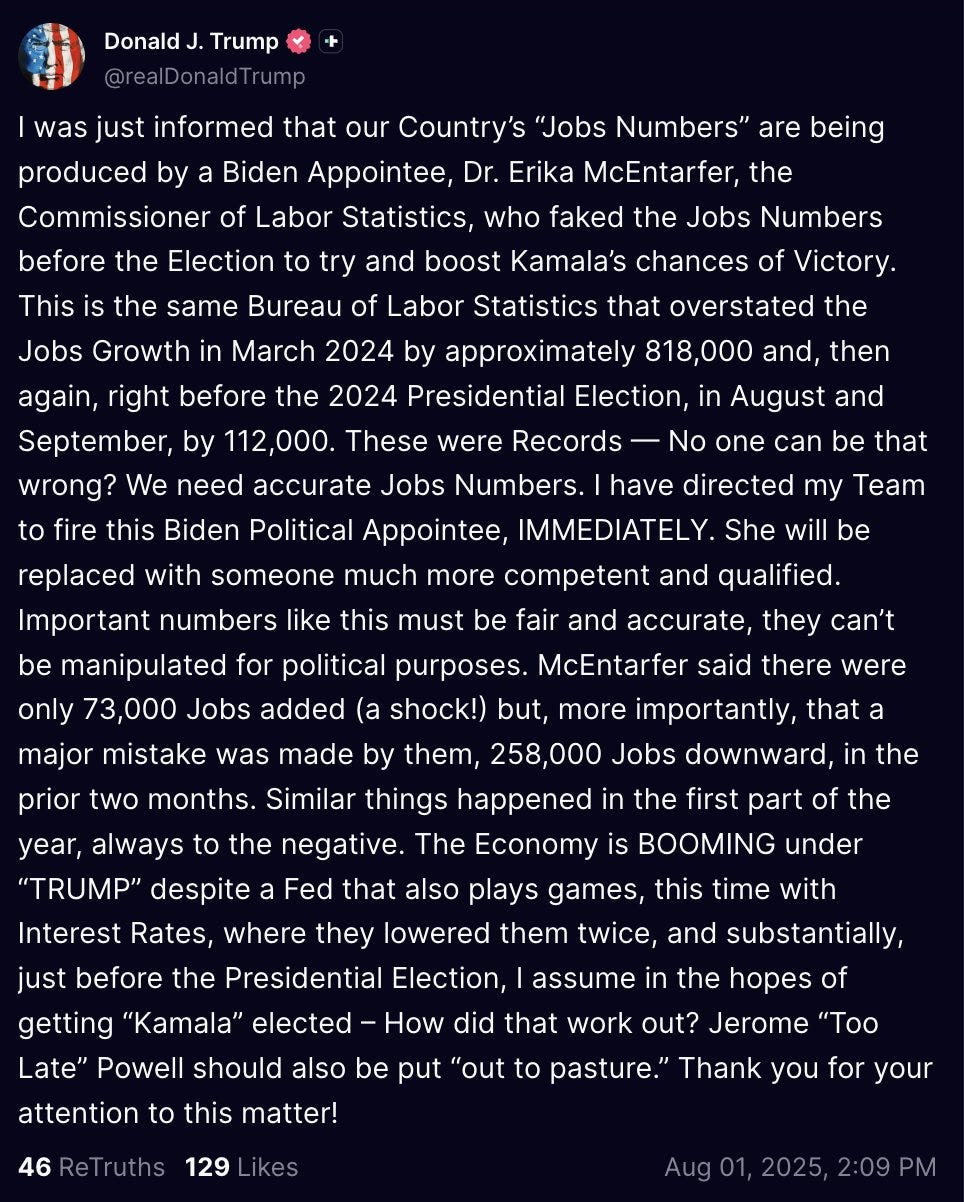

Alas, we have chosen to shoot the messenger along with a bold post that says ‘we are shooting the messenger,’ as in we got revisions to a jobs report that Trump didn’t like so he fired the Commissioner of Labor Statistics and accused her of ‘faked job numbers.’

Dow: Banana, meet Republic.

Jonah Goldberg: It’s like a pilot smashing the altimeter because he doesn’t like the altitude reading.

To the extent the people angrily responding to this are A) People and not bots B) Sincere and not partisan hacks or C) Not complete idiots:

Trump blamed the bad numbers on political bias. The same head of BLS delivered terrible numbers on the eve of the election (a fact Trump now lies about). She also delivered great numbers earlier under Trump. So the argument she was biased is just stupid.

Those trying to justify this keep getting details wrong and having others turn out rather inconveniently for them, such as the number he says was ‘rigged’ right before the election later being revised upwards rather than downwards, meaning the error favored him.

Nick Timiraos: Trump to CNBC on the jobs numbers before the election: “The numbers were rigged.”

He’s getting his dates wrong. He’s saying the jobs numbers looked good before the election but were revised down after the election. The big downward revision in August, before the election.

Kernan to Trump: You’re undermining confidence in the numbers by firing the BLS commissioner.

Trump: “When they say nobody was involved, that it wasn’t political…. Give me a break.”

Trump: “It’s a highly political situation. It’s totally rigged.”

Kernan: Which number do you believe? The chances of a Fed rate cut are going *upbecause of these weak numbers.

A slight slowdown in labor “will get you what you want” on the Fed.

This of course compounds the undermining of confidence. It seems actively designed to undermine confidence in the numbers.

Here is the director of the NEC outright saying that the data ‘has to be something you can trust’ and by ‘you can trust’ he means a high number that makes people do the things we want them to do. As in, the job of the numbers is to lie.

I appreciate the candor about the intent, sir.

Kevin Hassett (Director of the National Economic Council): “The data can’t be propaganda. The data has to be something you can trust, because decision-makers throughout the economy trust that these are the data that they can build a factory because they believe, or cut interest rates because they believe. And if the data aren’t that good, then it’s a real problem for the US.”

Justin Wolfers: Minister for Propaganda says the data can’t be propaganda once his Ministry has had a chance to vet them and ensure they’re even true-er.

Matt Darling: The White House anti-BLS webpage is basically nonsense. They claim a “consistent pattern” of “overly optimistic numbers” in 2024, but neglect that 2024 had 6 upward revisions and 6 downward revisions.

Aaron Rupar: Kevin Hassett suggests the Bureau of Labor Statistics rigged the 2012 election for Barack Obama.

Arin Dube: It’s critical to push back against baseless claims about data revisions, like those by Kevin Hassett. These falsehoods smear the integrity of professionals such as @brent_moulton, who have spent their careers ensuring the public has access to reliable economic data.

Brent Moulton: In 2012, I was the associate director at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (*not BLS*) and was responsible for preparing the estimates of gross domestic product. Mr. Hassett gets several things wrong here.

First, I would like to assure you that in the 19 years I was responsible for the GDP estimates (from 1997 to 2016), the estimates were NEVER politically manipulated, nor did anyone ever ask me to adjust them for political reasons.

At BEA we made a concerted effort to openly explain to our data users the data sources for the GDP, what methodologies were used in the estimation, and be as transparent and “open source” as possible. We provided source data tables, methodologies, technical notes, etc.

I disagree with Hassett’s allegation that the advance GDP estimate for the 3rd quarter of 2012 was unexpectedly large. That first estimate said that GDP grew at a 2.0% rate – just about what it had been averaging for the prior two years.

A number of forecasters try to predict the GDP estimate, often using much of the same source data as used by BEA (albeit usually calculated in less detail). For example, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNOW forecast (one of the better ones) was 1.8%, close to BEA’s 2.0% estimate.

[thread continues as you would expect]

Then, as the replacement, Trump nominated E.J. Antoni, which seems like a caricature of the worst possible nominee.

Brendan Pedersen: Trump makes the nomination of EJ Antoni to lead the Bureau of Labor Statistics official after firing the last commissioner over job report revisions. Antoni is chief economist at the Heritage Foundation.

Brian Albrecht (Chief Economist, Law and Economics Center, lacking imagination): Worse than I could have imagined 24 hrs ago

Ben Berkowitz, Emily Peck (Axios): President Trump’s nominee to head the Bureau of Labor Statistics, E.J. Antoni, suggested the possibility of suspending the bureau’s flagship monthly jobs report.

Christopher Rugaber (AP): Jason Furman, a top economist in the Obama administration, wrote on X: “I don’t think I have ever publicly criticized any Presidential nominee before. But E.J. Antoni is completely unqualified to be BLS Commissioner. He is an extreme partisan and does not have any relevant expertise.”

E.J. Antoni (June 26, 2024):

His Twitter feed is, shall we say, sobering throughout.

The National Review summary of the situation is ‘Trump Wants a Bureau of MAGA Statistics.’ The National Review.

Dominic Pino: What Trump would like is a BLS that is biased in his favor. The latest proof of that is his nominee to be the next commissioner, E. J. Antoni.

Antoni is the chief economist at the Heritage Foundation. He has been a relentless booster of Trump’s policies on social media. And he has demonstrated time and again that he does not understand economic statistics.

Dominic then provides various receipts about Antoni. He is maximally unqualified, as in far more unqualified than Jon Snow, who knows nothing.

This is all a whole different level of absurd and awful than usual.

Technically it is illegal to suspend the report but do you expect that to stop them?

Conor Sen: The BLS thing just sucks, anyone who tries to sugarcoat it at best doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Not that it will work, as Nate Silver explains at length, no one is going to be fooled. Destroying the reliability of our economic data only makes everything worse. Derek Thompson calls it part of ‘the war against reality.’

Greg Mankiw, a conservative economist and chair of the Council of Economic Advisors under George Bush who I’ve had on my RSS feed for a decade joined fellow former CEA chair Cecilia Rouse to warn that this firing will backfire and hurt the ability to analyze the state of the economy and develop the best policies, with the headline warning this will ‘come back to haunt’ Trump. You can smell the forced politeness.

It’s a relatively minor point relative to not shooting the messenger, but the defenses claiming the messager was terrible have just been so absurdly bad.

Chamath Palihapitiya (All-In Podcast): Non Farm Payrolls are total garbage so I asked Grok:

“Hey Grok, go look at the Bureau of Labor Statistics website for their non farm payrolls data. Tell me how many times their original forecasts have been revised since Jan 2020. And, of those revisions, how many times the data was revised up versus down. Categorize this during the Biden versus Trump presidencies.”

Bottom line is that BLS isn’t so much conspiratorial as it is inadequate in its approach. They are all over the place and add little directional signal. They constantly revise and in both directions.

The sampling techniques they use are brittle and don’t work for a large and dynamic economy like the US.

Trump was right to fire the head of BLS because she ran a critical aspect of the US economic machinery in an unpredictable, haphazard and sloppy way.

There needs to be a new, oracle-like data provider for this critical information.

Alex Tabarrok: Amazing. Expects to find bias. Finds none. Which is what you would expect if BLS is doing their job well.

Reverses course and claims BLS lack of bias means their forecasts have no “signal” and that is bad? Incoherent. Ends with gratuitous call for better methods.

Christopher Clarke: BLS preliminary estimates have actually increased their accuracy over time. There is always room for improvement and survey responses have decreased. Improved accuracy requires more resources, not less.

What BLS does is they provide an early estimate, because that is valuable even when it is noisy, and then a later estimate. This Is Good, Actually.

Tyler Cowen, who has had some very let’s say creative defenses of various administration decisions, flat out made it is very bad to behave this way, and that BLS is not biased except in favor of following established procedures, as in it is biased towards being above reproach about potential biases. Which is wise, and means if you want to account for other things you need to do that on top of their estimates.

On top of everything else, the whole thing happens to be backwards in two distinct ways.

As in, the first way is that downward revisions mean the numbers were initially overstated, which makes you ‘look good,’ and no one involved is buying the galaxy brain (but kind of correct) take that you want to ‘look bad’ to get a fed rate cut.

Ernie Tedeschi: The average revision to monthly payroll employment during the Biden Admin–from 1st estimate to final/latest–was -0.05%. For the 1st Trump Admin, it was -0.10% (same including the pandemic or not). These are both small revisions, but the “overstatement” was greater under Trump.

The second way this is backwards is that low numbers mean you can get the Fed to lower interest rates, which is what Trump wants, so he should welcome that.

Nick Timiraos: Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent suggested that the Fed should consider cutting interest rates by a half percentage point at its September meeting in light of recent labor-market data showing a slower pace of job growth

Bharat Ramamurti: The job numbers are all fake and Mr. Trump’s economy is actually BOOMING! But also the Fed should cut by 50 bps despite accelerating inflation because the job market is so bad.

This is very much not an isolated incident. The Trump Administration is cutting our ability to measure things across the board.

It is easy to say to all of this ‘oh this is at this point entirely unsurprising’ or dismiss it as unimportant. I believe that would be a mistake. This type of action is a big deal, and falls into the list of things you absolutely never do. Do not shoot the messenger, violate a flag of truce or break guest right. Ever. If you do, The North Remembers.

As in, recently I finally got around to watching The Godfather, and then it was clear that everyone involved expected everyone in their culture to go around shooting messengers (and shooting people at peace talks) and that’s when I lost the ability to sympathize with the characters.

Colin Grabow offers a central thread outlining the forces keeping the Jones Act in place and how they work to prevent America from shipping goods between ports. If you’re following Balsa then you know most of this already.

There exist true things that are forbidden to talk about.

There also exist a lot of false things that are forbidden to talk about.

Peter Boghossian: One deliverable from Peter Thiel’s talk: If it’s forbidden to be spoken about, it’s likely true.

Emmett Shear: We taboo all kinds of claims, and only some of them are true. For example, claiming the earth is flat will get you excluded from society, but that doesn’t make it true. If only finding truth was as easy as inverting taboos!

Zac Hill: I mean that’s just straightforwardly not the case right? Also who is doing the forbidding and why are people running around like simps preoccupied about what is and isn’t sanctioned? “Ahh the Arian Heresy is obviously 100% factually accurate.” Just seems like a red herring idk.

Daniel Eth: This is very obviously false to anyone who thinks about it for more than a couple seconds. There’s a related point that EVEN THOUGH most things that are “forbidden” to be spoken about are false, we should taboo less b/c SOME are true and important. But that ain’t this

Arthur B: There’s sadly a cohort of people who defend hyperbole or outright nonsense so long as the direction is correct because it makes the message punchier, as if the rhetorical end justified the means. But such discourse habits destroy the commons.

Paul Graham: It’s not true that if you can’t say something, there must be a kernel of truth in it. It’s trivially easy to think of counterexamples.

What’s the best model of being unable to ‘work your way up from the mailroom’?

Here is one attempt.

Byrne Hobart: One way to frame this is to ask what would have to happen to have a modern Sidney Weinberg-style career, which is mostly a list of what would have to not happen. He’d have to:

-

Avoid finishing high school.

-

Avoid taking any standardized test.[1]

-

Kept his early business hustle under wraps.[2]

-

Avoided college.

-

Not found a company where there’s a career track that starts at “unskilled worker earning subsistence wages” and somehow has a path to the top.

Another way to say that is is that you only get Sidney Weinberg stories when the market for talent is fairly inefficient.

…

But you can flip that around and give it a grim corollary: the measure of how efficiently talent is allocated in a society is how young you are when your dreams are crushed. A world where 99.9th percentile talent immediately gets snapped up by whichever employer can make the best use of that talent is one where 99.8th percentile people learn early on that they just don’t have what it takes.

…

There is still a path for dropouts with few legible skills to work their way up to the top of a Fortune 500 company: start at the top, and stick around until your company is on the Fortune 500.

I think this is mostly a case of romanticizing a path that was never great in the first place. It’s not that it is impossible to ‘work your way up’ in this fashion, if you actually are good enough that you would deserve it, it’s that if you could impress enough to actually pull it off working your way up then you have much better paths, with or without going through college. That’s also largely about the great news that we have much better skill and reputation transfer, so you’re not permanently at the mercy of the firm and your boss.

I also very much don’t think it means your dreams die quickly if you are ‘only’ 99th percentile or 99.8th percentile talent. A hypothetically perfect sort where relative talent is static would do that, but neither half of that is true. Nor do you get locked out of most ‘dreams’ worth having if you get somewhat off track. There are certainly some that do have strict tracks, but they are that way because they are oversubscribed and mostly generic dreams and even then you mostly have redraws if you care enough.

John Wentworth offers Generalized Hangriness: A Standard Rationalist Stance Towards Emotions. Being angry because you are hungry means your anger is ‘wrong’ in its explicit claims, but it contains the useful information that you are hungry. Thus, the correct stance towards experiencing an emotion is to ask what information it actually provides you. A strong emotion is trying to tell you something is important, but you have to figure out what is the proper something.

Elizabeth: For readers who need the opposite advice: I don’t think the things people get hangry about are random, just disproportionate. If you’re someone who suppresses negative emotions or is too conflict averse or lives in freeze response, notice what kind of things you get upset about while hangry- there’s a good chance they bother you under normal circumstances too, and you’re just not aware of it.

Similar to how standard advice is don’t grocery shop while hungry, but I wouldn’t buy enough otherwise.

You should probably eat before doing anything about hangry thoughts though.

Benquo: Unless you’ve observed that you tend to unendorsedly let things slide once you’re fed. In that case, better do something about the problem while you’re hangry.

I would generalize this even further than Ben Pace does here:

Ben Pace: This rhymes with how one treats feature recommendations from users. It is typically the case that a user advising you to make a change does indeed have a problem when using your product that they’re trying to solve, and you should figure out what that problem is, but their account of how to solve it (what ‘improvement’ to make) is usually worth throwing out the window.

Emotions also have practical effects beyond their information content, so you want to watch out for and optimize those as well. One aspect John does not get into is that you need not take your emotional responses as givens.

John Wentworth also notes that his empathy is rarely kind, that trying to imagine things from someone else’s perspective can easily lead to the exact opposite of empathy if you would then view their decisions, in particular their lack of effort or willingness to apply effort to fix things, with disgust. Several comments point out that this could be seen as a failure to model their actual cognitive state, but why should we presume that should lead to empathy? The general case version of this resonates with me quite a lot.

Diverse workforces do not seem to lead to greater (or lesser) profits, and the supposed McKinsey study people keep citing to claim the contrary, as far as we can tell, fake.

Santi Ruiz: The McKinsey study that claimed diverse workforces lead to bigger profits was always fake (they won’t share data, it doesn’t replicate for the S&P 500 or other settings, and it doesn’t make sense). But fake social psych research is a demand problem, not just a supply problem.

I disagree that the finding doesn’t make sense. Like many things in social psych, you can tell a plausible story of effects in either direction, or of no effect.

A firsthand report of a jury trial (for molestation) in Georgia.

True story:

Patrick McKenzie: I think many people would be surprised at the difficulties billionaires have in converting money into smart people and/or their outputs.

Casey Handmer: It is so hard that for essentially anything non trivial it still has to be done personally.

The examples of this are too numerous to count. Musk’s companies could not have succeeded unless he was in the driver’s seat for much of the time. By contrast, Google X, Virgin rockets, Blue Origin all had the best people and tech that money could buy – but it wasn’t nearly enough.

I see this on an almost weekly basis now. Anything sufficiently interesting is not fungible in money. The supply is extremely inelastic.

You must have an army of stringently curated and boldly led mechanical engineers.

Paper offers a bizarre thesis, that algorithmic collusion between sellers on a platform like Amazon helps consumers because they collude to lower advertising costs and this outweighs the effect of colluding directly on price. I notice my skepticism because if within-platform ads raise less revenue the platform should reclaim those costs via higher commissions, which should raise prices by the same amount. I note that o3 thought that there wasn’t room for Amazon to do this, but that’s weird.

Did the UK’s dominance fail because of emigration away from the home islands? The argument here is that developed economies don’t diverge that much on GDP per capita, but I don’t think this means the UK keeps similar GDP per capita in the alternative world, especially if we’re not on the margin and talking about 200 million people living there. The OP admits those people staying home would be a loss of welfare but I also assume it would have made the UK a lot poorer and also that population would have balanced largely in other ways.

A much better and simpler story is that the UK home islands simply didn’t have enough land and natural resources, which is why there was so much emigration in the first place? Europe was never going to be able to sustain its economic advantages indefinitely.

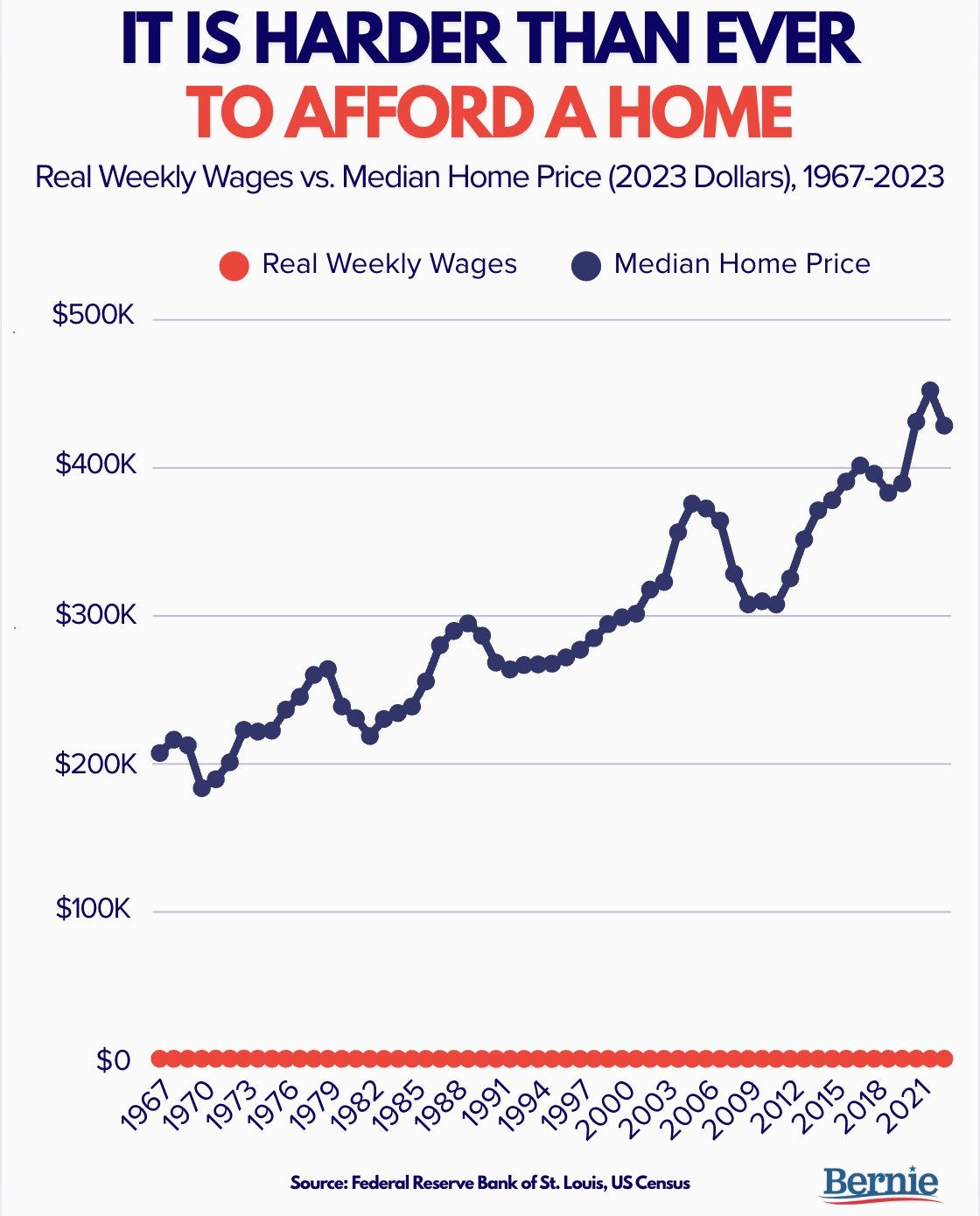

And of course in recent times, the UK has been dying mostly of self-inflicted wounds, such as effectively banning the construction of housing, and now the saying of words.

An excellent point:

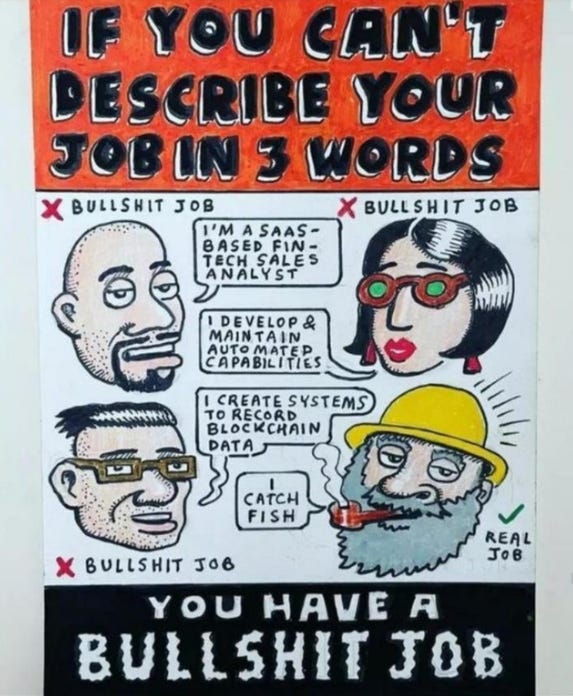

Byrne Hobart: An interesting corollary to this is that the more words it takes for someone to explain a concept to you, the greater the proportion of jobs you’ll dismiss as “bullshit jobs.” I’ve observed this, too!

Note that the jobs here could be described in three words just fine, all you have to do is lose a little detail, on the level that ‘I catch fish’ simplifies fisherman. He doesn’t catch all fish everywhere, after all.

-

Software sales analyst.

-

Improve automated capabilities.

-

Create blockchain recorders.

Only three words is largely about negative space. Observe these job descriptions I brainstormed quickly:

-

Sit at desk.

-

Let boss yell.

-

Fetch the coffee.

-

Pitch investors.

-

Diversity training monitor.

-

Cash the check.

Also some good ones in the replies, like ‘I send emails’ or ‘creating shareholder value.’

Also note that it’s ‘if you can’t do it, it’s bullshit’ not ‘if you can do it, it’s not bullshit.’

Why does the trick still mostly work? Because the fact that you have a bullshit job predicts not that you can’t describe it in three words, but that you will choose not to.

Polymarket is on its way back to (being fully legal in) America, baby!

Shayne Coplan: Polymarket has acquired QCEX, a CFTC-regulated exchange and clearinghouse, for $112 million.

This paves the way for us to welcome American traders again.

I’ve waited a long time to say this:

Polymarket is coming home 🇺🇸🦅

Owning a DCM and DCO will let us serve all American traders and brokerages.

This acquisition isn’t just about a license; it’s Polymarket’s homecoming, returning stronger and ready to serve American users once again.

The best part about this is that this comes on the heels of the BBB plausibly making professional sports betting essentially illegal in America, since you can only deduct 90% of losses while being taxed on 100% of gains. If that is applied to individual wagers, then no one has an edge big enough to overcome it, so gamblers would have to either give up the gambling or give up on paying their taxes.

But if you buy a sports futures contract under CFTC rules, then you get normal tax treatment, and you’re back in business.

This could all end up being a blessing in disguise. The current licenced sportsbooks in America offer highly non-competitive pricing, focus on pushing you towards predatory behaviors and products, and aggressively limit winners. Once Polymarket gets sufficient liquidity, trading there is remarkably cheap, and you are naturally pulled towards behaviors that have little cost even if you are betting at random.

However bad you think companies like FanDuel are, they’re worse.

Ryan Butler: FanDuel reports 16.3% sportsbook gross gaming revenue margin in June, the highest mark in company history

This is roughly triple Nevada sportsbooks’ historic hold percentage from before FanDuel launched its book in 2018.

There is no way to make 16.3% profit on wagers in general without being deeply, deeply predatory, even if all of your customers are suckers. Someone betting a normal NFL line fully at random only loses 5%.

Argentina’s salaries outgrow profits as share of GDP, despite the fact that real public sector wages have been falling.

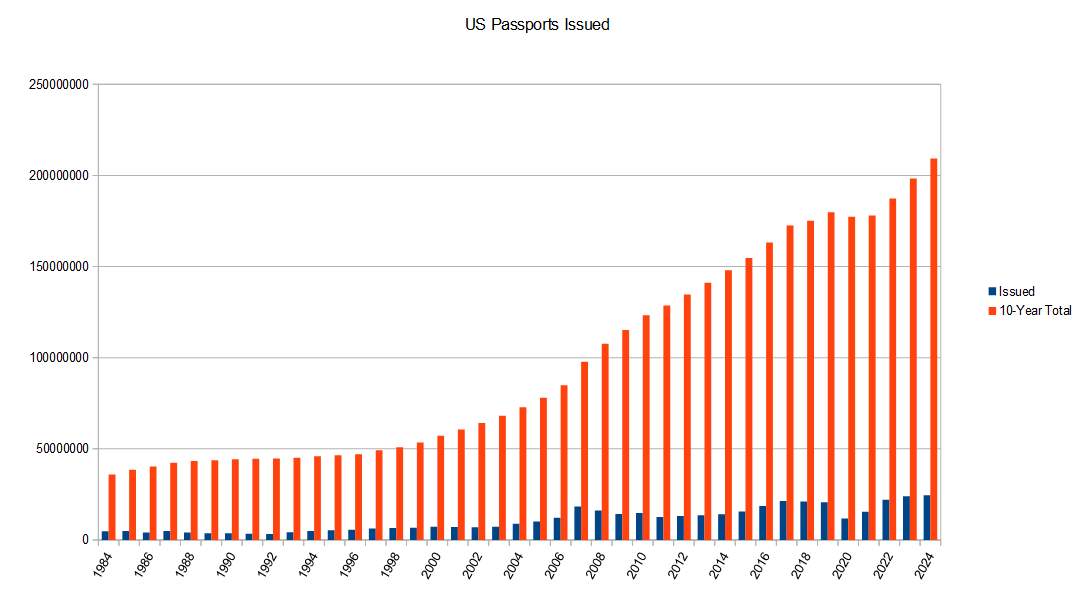

Whenever there is a graph that blows your mind every time you see it, chances are good it turns out to need a correction. Despite that, the corrected graph (the one shown below) is still rather mind blowing.

The Rich: people have no idea what life was like before they were born

If a statistic or claim sounds absurd and wrong, you can check the sources. Often this reveals the whole thing was bogus. Thread has some examples, several of which I can confirm because I too checked the sources or otherwise know the story.

We could stop spending so much time at airports simply by not telling people to spend so much time at airports. Who is telling people to get there 2.5-3 hours before their flights? Why in the world? I am in the ‘never miss a flight’ camp, and even then one hour is fine if it is reliable (e.g. you are taking trains).

Remember those claims that gas stoves caused large increases in asthma cases? That study had a major conflict of interest and also didn’t hold up, once corrected the impact was not significant.

You can identify outlier people by noticing you cannot predict what they are going to say next. That is not always good, but it often is very good. Whereas most people rarely break out of predictable scripts. Which in many circumstances is also good.

The theory that all the abundance and YIMBY progress can largely thank the MCU version of Thanos, as in Marvel finally making a Population Bomb Guy the villain.

Whereas yes, a large portion of children’s media has been for decades or more straight up eco propaganda and says the ultimate evil is humans wanting to build and do things, or even wanting to exist.

Roman Helmet Guy: “Remember that the Earth’s resources are limited. You do not need to have a big family, because all the world’s people are your brothers and sisters.” You live in the most propagandized society in history.

Joe Lonsdale: A top kids’ show for much of the ‘90s had Malthusian / anti-natalist, globalist nonsense alongside its eco proselytizing.

It’s not a coincidence; if you go into its main backer Ted Turner’s office, a huge painting has his head in the sky, nearby a US flag turned into a UN flag.

Charles Fain Lehman: As my older son moves on from picture books, it’s stunning to me how much children’s media is just non-stop eco propaganda. “Humans are bad for the earth, you should feel guilty about this” is the constant message.

Matthew Yglesias: Paisley Paver did nothing wrong.

It is getting a lot easier to avoid. There is so much to choose from, so you don’t get whatever is on broadcast TV forced upon you, and similarly you can filter the books, and also the broader marketplace seems to be pulling things back. It’s still rough out there.

I love that yes, Trey Parker and Matt Stone can indeed keep getting away with this, and I love that Trump’s response to being attacked like this was to accuse the left of hypocrisy for being happy about it. That’s the spirit.

Megan McArdle on the cancellation of Steven Colbert’s The Late Show as reflecting the loss of shared culture. She oddly ties this to the extra 99 minutes a day we don’t leave the house, which historically was how people ended up watching late night, but now we watch more tailored content. Which in general is an improvement.

I do think there have been some fantastic late shows that I was happy to watch, in particular Taylor Tomlinson’s After Midnight and previously Craig Ferguson’s Late Late Show, or early Daily Show and Colbert Report, but I found most late shows bad and essentially unwatchable. That includes Colbert’s Late Show run, and I’m actually really happy for him to get a new show or podcast instead where he can do more interesting things. Free Colbert, as it were.

The Panama Playlists, see what various people listen to. Remember that Spotify playlists are public by default.

You can buy nonrefundable vacations from other people at a discount, typically 20%-30%, sometimes more especially with a last minute sale. According to WSJ’s Mark Ellwood the top sites that do this are legit and guard against fraud, pointing to SpareFare, Roomer, Plans Change and Transfer Travel, and on the high end Eluxit.

A discount does not mean a ‘good deal.’ Vacation markets are super duper inefficient. But also these are going to mostly be forced sellers, without natural buyers, and buyers might have gotten discounts to begin with by booking in advance, so if you can figure out what is a good deal (use AI for this?) you can probably find pretty good bargains.

The best part is that you have to buy one of a small number of particular packages. You avoid choices, and as we all know Choices Are Bad. Instead of comparing this vacation to all possible choices, and sweating planning and decisions, you take what is available and you show up and that is it. If something isn’t a great fit for your preferences, you have an excuse to go outside your comfort zone and you don’t feel like you punted. It actually sounds nice.

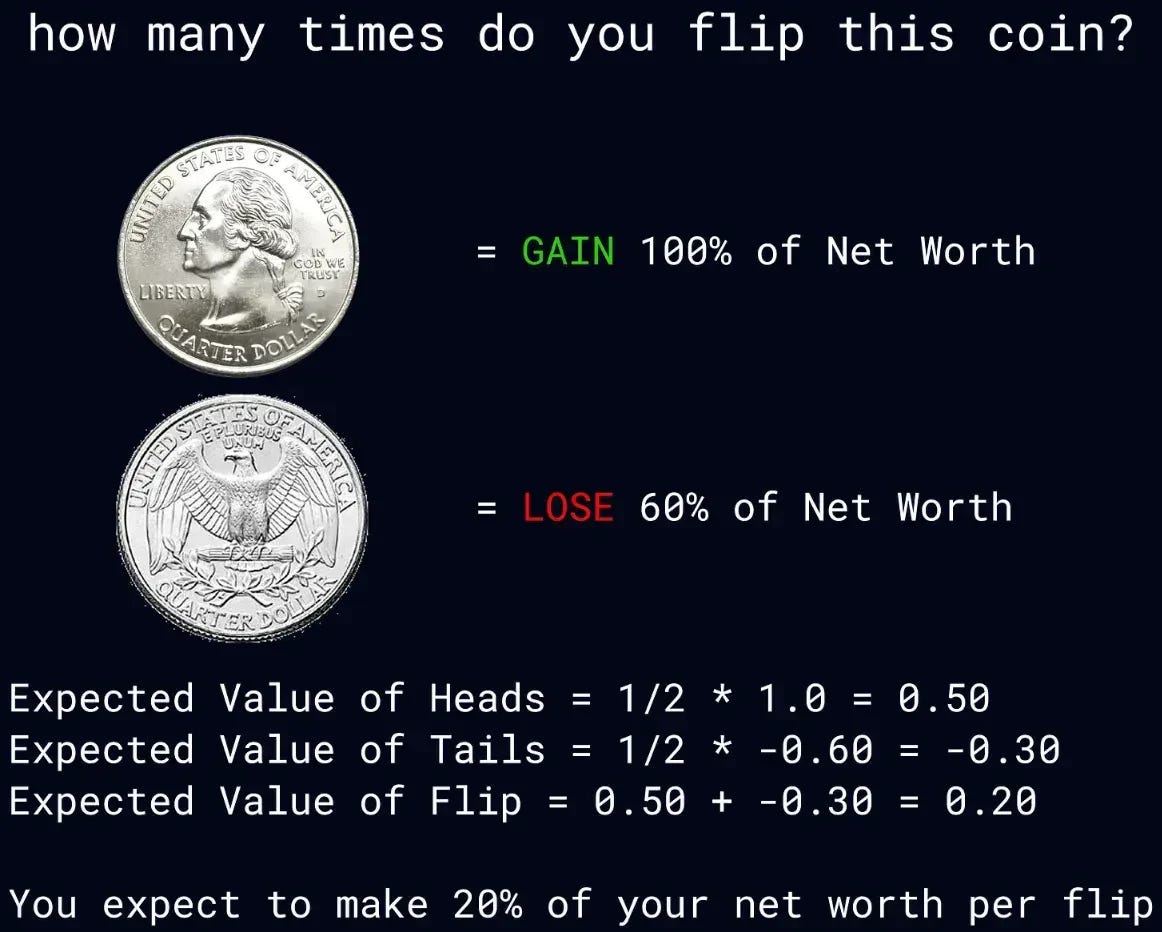

Thiccy Thot calls this ‘the jackpot age,’ with people not valuing survival or optimizing for mean results like they should, and urges people not to chase jackpots. As an illustration he offers this game, which is effectively a St. Petersburg paradox variant. The EV on each flip is great but the more you flip the more likely it is that you lose.

Assuming I cannot hedge the flip and no tax implications? I do notice I am past the point where I would flip, the marginal value of money is declining too rapidly.

Should Magic: The Gathering emergency ban either Agatha’s Soul Cauldron (galaxy-level move) or Vivi Ornitier (safe and obvious play), or accept that all the good players in Standard will be playing the same deck until the next window?

There is a long history in Magic of players discussing the need for emergency bans, and then mostly not getting such bans, as Wizards has placed very high value in sticking to its announcement windows outside of true emergencies. They’ve shown time and again they’d rather let Standard wither and be terrible for months on end. Usually there is a lot of talk about letting the players find a solution, long after it is clear that there exists no solution.

I have long disagreed with this policy. I disagree with it even more today, as information is found and spreads faster and there is tons of statistical data. Drop the ban hammer. Do it now.

Chess.com has a team of 30 people that ban 100,000 accounts per month for cheating and unfair play, 40% of the accounts get banned within their first two weeks. The article presumes this means they are doing a good job catching cheaters, but even if you assume minimal false positives that is not obvious. If we were doing a better job catching cheaters presumably people would be doing it less?

Optimization for thee but not for me, I insist:

Jorbs: looked something up about a game and someone posted that you should resolve an issue a certain way unless “you enjoy making suboptimal decisions” and that is such a funny thing for a human who spends their time answering rules questions on forums for board games to write.

Clair Obscura Expedition 33 continues to go well as I move into Act 3, despite some frustrating design mistakes.

One that I’m rather annoyed by is that at some point (not a meaningful spoiler) there is a character you pick that the game is telling you that you need to have in your party or they won’t learn their skills, similar to for example a Blue Mage in Final Fantasy V. I find this really annoying because that’s not who I enjoy having in the party on an aesthetic level, but it feels bad missing out, and even worse not knowing if any given battle is a place you would miss out. Grr. I’ve mostly decided I don’t care.

Even if you ignore that issue, the way upgrades work, both with Color of Lumina and weapon upgrades, effectively locks you into a party. I chose Luna and Maelle because I find that fun and more central to the plot. I’m happy with my choices but sad that the game punishes experiment like this.

Another main complaint is that balance is often lacking. Decisions that should be interesting instead feel forced. There’s also a big ‘too awesome to use’ problem with certain resources, especially Color of Lumina.

My biggest complaint is that it is very easy to get turned around, or for it to be otherwise unclear how to move on to the next area. Several times I have been extremely frustrated and effectively stuck, including right now as I type this inside the monolith. I am fine with navigation as an interesting puzzle or decision, but this does not feel like that.

There are a bunch of things in Act 3 that are deeply confusing or rediculous, but all of them seem highly optional. If you want to go completionist that’s your call.

I think I largely buy this argument that one job RPGs have big advantages over RPGs where you choose your class. They can do a lot more fun customization.

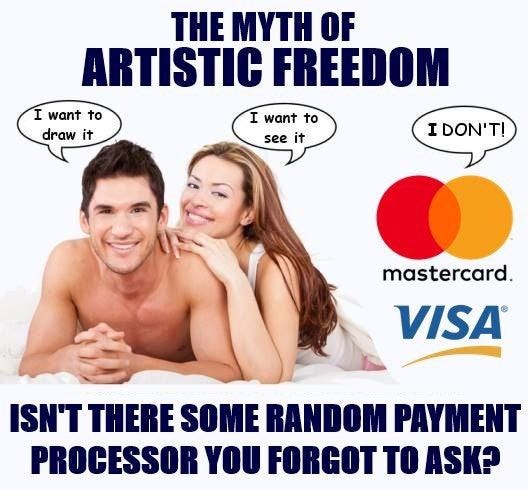

Itch.io apologises after, to satisfy its payment processor, nuking thousands of WSFW games with no notice. Those who have purchased the games report they cannot download them and no refunds are being offered, although itch.io claims they can still be downloaded. Payouts are halted. Itch.io claims the delistings will mostly be temporary and can be individually cured once they get their new house in order.

Then it turns out Stripe is only clamping down because their own banking partner is threatening to clamp down on Stripe, and they are themselves seeking a way out.

To summarize, this keeps happening:

To be fair to itch.io, they are over a barrel and do intend to bring the banned games back. They are looking for a new payment processor as a way out.

It seems Ross Vought might be behind all this push, including a general push to effectively ban pornography?

Worlds Beyond is doing amazingly well for Magic: The Gathering. Final Fantasy made them $200 million in one day, and doing far better than any previous set, so much so that they could not meet demand. I didn’t love the flavor details of many of the cards, clearly the market disagrees or cares little, and everyone says the limited format is great.

Even Lord of the Rings took six months to get to that point, and that set is still selling several years later. Spiderman is up next. They see Japan as a ‘potential gold mine’ for more material.

Perhaps this was always the endgame for Magic. We had decades of our own storylines and worlds, but once Magic went sufficiently big and mainstream and moved away from competition and two-player games towards Commander, being the meta-IP for all of fantasy (and perhaps beyond it) makes too much sense, and it will only feed on itself until and unless it wears the product out.

This also seems like a solution for running out of design space. There’s no shame in it after three decades. Magic has mostly fully mined the simple stuff that works, forcing complexity to drift higher and the mechanics that work are getting continuously recycled, even if they get new names. If you want to have higher complexity and repeat mechanics forever, top down is where it is at.

Boen seems largely correct here:

Boen: we used to joke about this, but gambling mechanisms, metagame progression, interaction extenders, timewasting filler etc has all become so commonplace that most people genuinely just think that that’s what videogames are now & get confused/angry when you say that stuff is bad.

“metagame progression” is specifically like call of duty where a leveling system strings players along with little upgrades to keep playing. many stop after reaching max lvl, which betrays the fact that the “real game” is unfortunately shallow and boring absent external incentive

Andre Treiber: I’m with you on a lot of these, but I actually really enjoy meta progression as a mechanic. I really enjoy roguelite experiences and unlocking new things and making old challenges grow trivial is a rewarding part of the gameplay.

Boen: Yeah there’s some subtlety here. I think that the type of thing people mean by “meta progression” in the context of roguelikes and stuff like that, is actually much more akin to regular game progression, not meta at all, which is of course a pillar of game design & not a problem.

Roguelite metagame progression can be very good. I especially like it when you are unlocking additional abilities over time while you are not close to winning the run, and when the amount of progression you make determines what you unlock and is part of strategic decision making.

What annoys me quite a bit are situations in which you are reliably winning runs, there are higher difficulties that would be interesting, and the game wastes a bunch of your time getting to them. The worst version of this is when you are winning your runs but also unlocking capabilities faster or almost as fast as the extra difficulty kicks in, so the game doesn’t get harder for a long time and you’re skilling up on top of that. The central example of this I remember is Roguebook.

The other stuff is really terrible. The thing is, you could simply not do these things? Unless you are getting them on microtransactions there is no real advantage to keeping a player playing Call of Duty for 100 hours instead of 50 hours, not having any fun. Many games are using these techniques without the microtransactions. Stop it.

As per Manifold, current expectations are for roughly 600k Waymo rides per week by EOY 2025, and perhaps 1.5 million per week by EOY 2026. I’m definitely sad we cannot go faster.

Boston’s unions attempt to ban driverless taxis, because They Took Our Jobs. The statements at the debate were even more absurd than I expected, which is on me.

Timothy Lee: Mejia considered it “very triggering” for Waymo to use the term “driver” to describe a technology rather than a person.

…

City Councilor Benjamin Weber found it “concerning to hear that the company was making a detailed map of our city streets without having a community process beforehand.” He added that “it’s important that we listen when we hear from the Teamsters and others who feel as though they’re blindsided by this.”

“I think it’s important that we pause—sometimes we rush—and make sure everyone’s voice is heard before anything happens that we can’t turn back from and that protections are in place for our workers,” said City Councilor Erin Murphy.

The next day, Murphy announced legislation requiring that a “human safety operator is physically present” in all autonomous vehicles—effectively a ban on driverless vehicles. Given the near-unanimous hostility Waymo faced at the hearing, I wouldn’t be surprised if Murphy’s proposal became law in Boston.

There is good news elsewhere:

On the other hand, legislators in Washington DC and New York State have introduced bills to open the door to driverless vehicles—though it’s not clear if these bills will become law. Legislators in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia could also act on driverless vehicle technology in the next year or two.

Timothy Lee, who is an expert at following developments here, fears that blue states and cities might indeed ban self-driving cars, and we could get to a 2035 where red states had tons of autonomous vehicles and blue states and cities have none.

It is not impossible, and certainly some amount of delay is in general likely, but I think we are going to win this one rather easily over time. It is impossible not to notice how much Waymo has improved San Francisco and other cities, and how much more it will improve it when supply goes up and thus costs and wait times go down. The lifestyle impact is dramatic and I do not expect the public in blue cities to accept being left behind.

Alec Stapp: We should be much more explicit about the tradeoff here:

The Teamsters are demanding that we let thousands of people die in car crashes in order to protect their jobs.

Chris Freiman: When Teamsters try to block life-saving technology to protect their jobs.

Alec is not wrong about self-driving cars preventing deaths, yet I would prefer to not make that the main argument. Quite often the protectionist laws, including union rules and things that destroyed childhood in America, are imposed in the name of that same ‘otherwise people will die’ style of rhetoric. What we should focus on are the far more important and massive other transformative benefits.

The jobs that they are trying to ‘protect’ are worse than useless. We would be requiring that people be paid to sit in cars and drive them all day, mostly not enjoying doing this or otherwise benefiting, doing the task worse than the AI could, in order to justify a transfer of wealth to those people.

Adam Thierer, together with Mark Dalton, proposes Federal-level regulation on self-driving, allowing Level 4-5 automated driving systems (ADS) nationwide under a new safety framework under the extremely poorly named ‘America Drives’ act (since this involves America not driving, that is the entire point).

The parallels and contrast to the insane AI moratorium are obvious, with concerns about ‘patchworks of state and local laws’ and localities doing crazy things like requiring a human driver be present as per Boston above.