You can now have o3 throw vastly more compute at a given problem. That’s o3-pro.

Should you have o3 throw vastly more compute at a given problem, if you are paying the $200/month subscription price for ChatGPT Pro? Should you pay the $200, or the order of magnitude markup over o3 to use o3-pro in the API?

That’s trickier. Sometimes yes. Sometimes no. My experience so far is that waiting a long time is annoying, sufficiently annoying that you often won’t want to wait. Whenever I ask o3-pro something, I often also have been asking o3 and Opus.

Using the API at scale seems prohibitively expensive for what you get, and you can (and should) instead run parallel queries using the chat interface.

The o3-pro answers have so far definitely been better than o3, but the wait is usually enough to break my workflow and human context window in meaningful ways – fifteen minutes plus variance is past the key breakpoint, such that it would have not been substantially more painful to fully wait for Deep Research.

Indeed, the baseline workflow feels similar to Deep Research, in that you fire off a query and then eventually you context shift back and look at it. But if you are paying the subscription price already it’s often worth queuing up a question and then having it ready later if it is useful.

In many ways o3-pro still feels like o3, only modestly better in exchange for being slower. Otherwise, same niche. If you were already thinking ‘I want to use Opus rather than o3’ chances are you want Opus rather than, or in addition to, o3-pro.

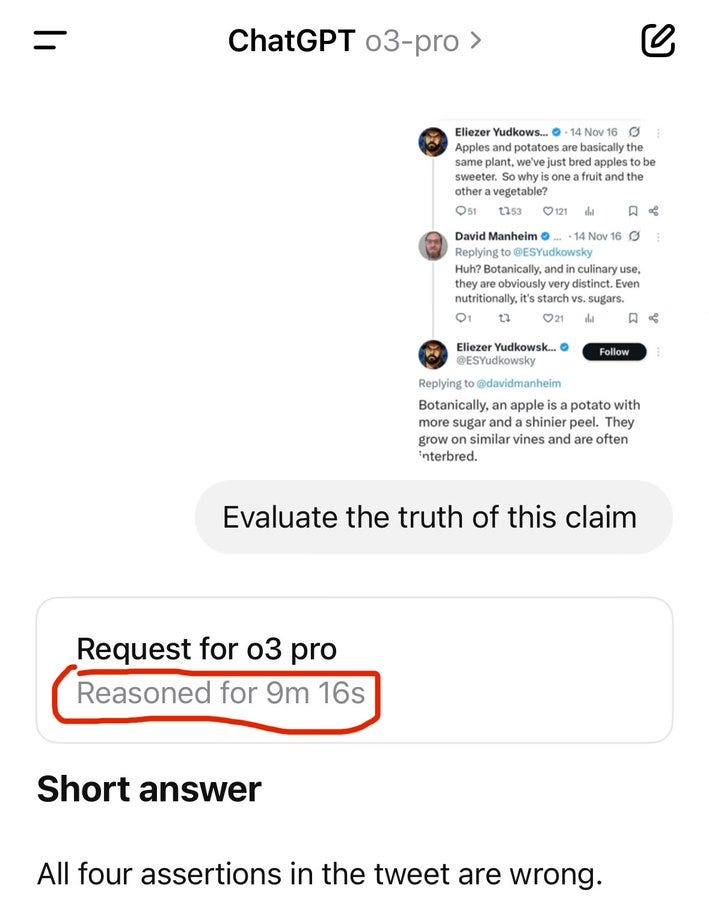

Perhaps the most interesting claim, from some including Tyler Cowen, was that o3-pro is perhaps not a lying liar, and hallucinates far less than o3. If this is true, in many situations it would be worth using for that reason alone, provided the timing allows this. The bad news is that it didn’t improve on a Confabulations benchmark.

My poll (n=19) was roughly evenly split on this question.

My hunch, based on my use so far, is that o3-pro is hallucinating modestly less because:

-

It is more likely to find or know the right answer to a given question, which is likely to be especially relevant to Tyler’s observations.

-

It is considering its answer a lot, so it usually won’t start writing an answer and then think ‘oh I guess that start means I will provide some sort of answer’ like o3.

-

The queries you send are more likely to be well-considered to avoid the common mistake of essentially asking for hallucinations.

But for now I think you still have to have a lot of the o3 skepticism.

And as always, the next thing will be here soon, Gemini 2.5 Pro Deep Think is coming.

Pliny of course jailbroke it, for those wondering. Pliny also offers us the tools and channels information.

My poll strongly suggested o3-pro is slightly stronger than o3.

Greg Brockman (OpenAI): o3-pro is much stronger than o3.

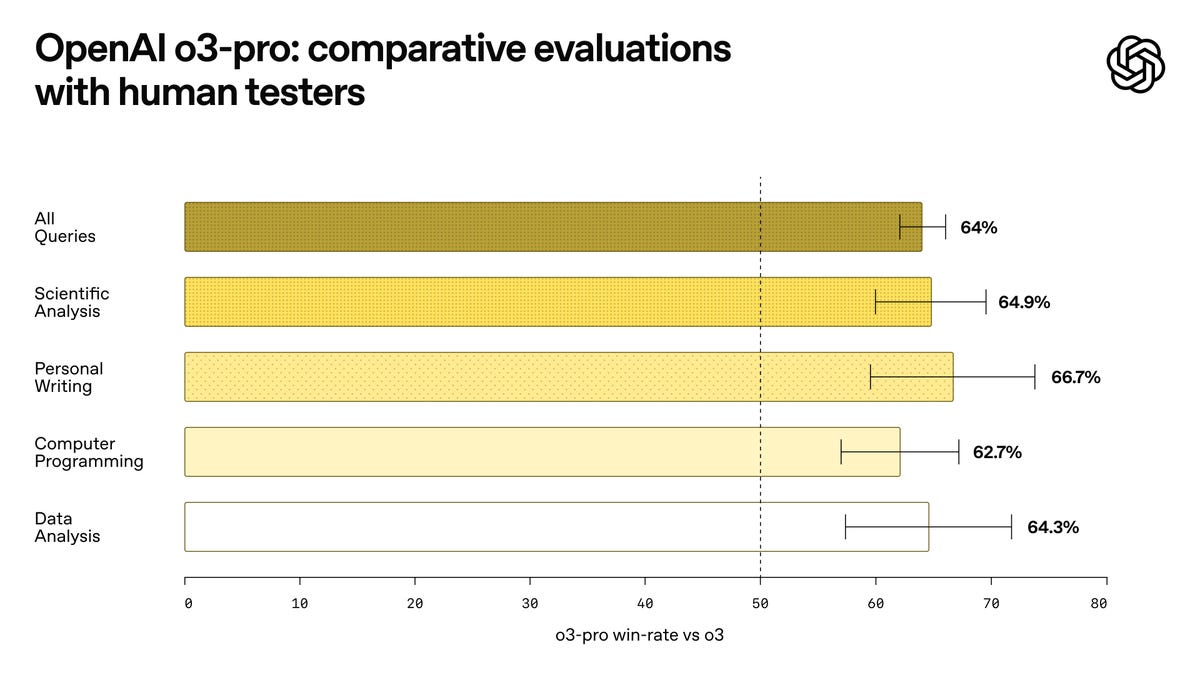

OpenAI: In expert evaluations, reviewers consistently prefer OpenAI o3-pro over o3, highlighting its improved performance in key domains—including science, education, programming, data analysis, and writing.

Reviewers also rated o3-pro consistently higher for clarity, comprehensiveness, instruction-following, and accuracy.

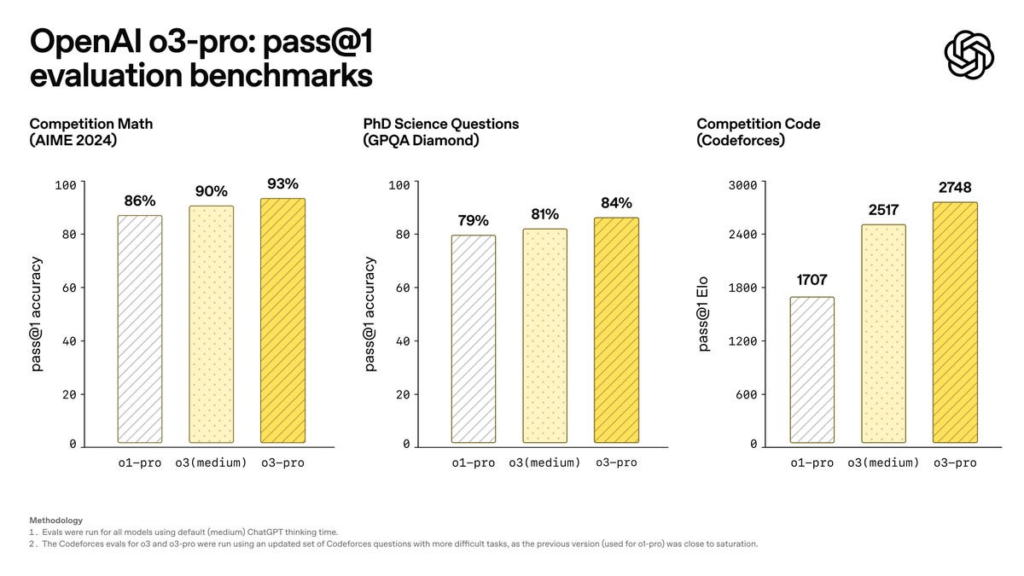

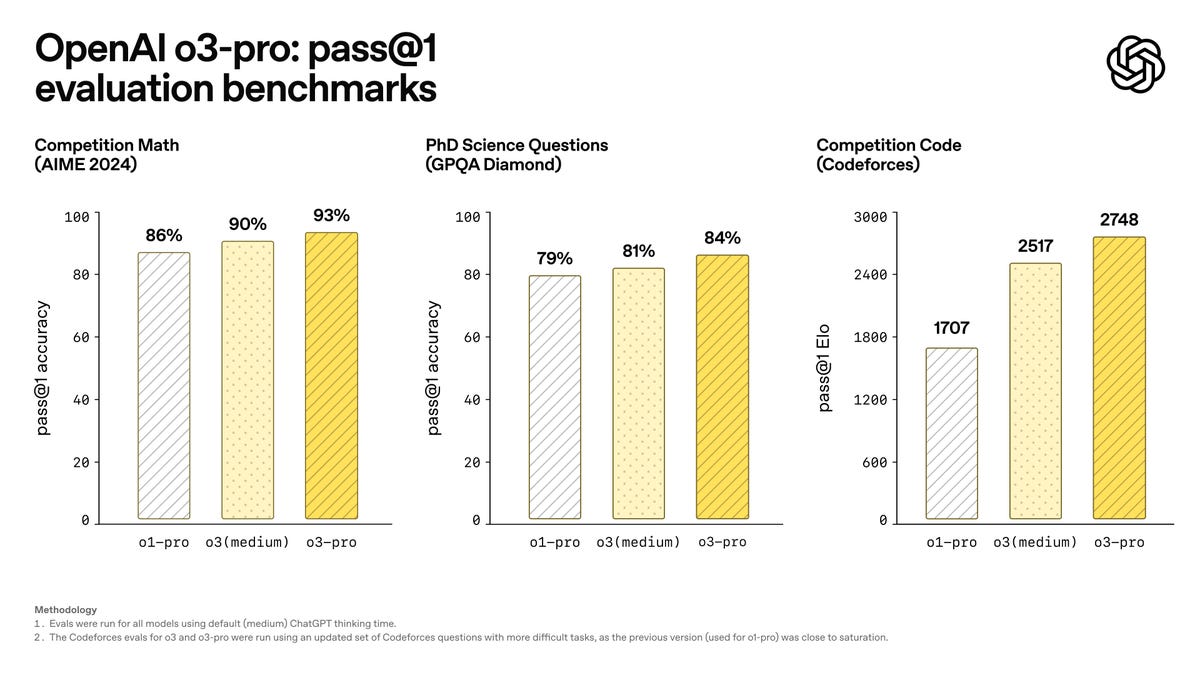

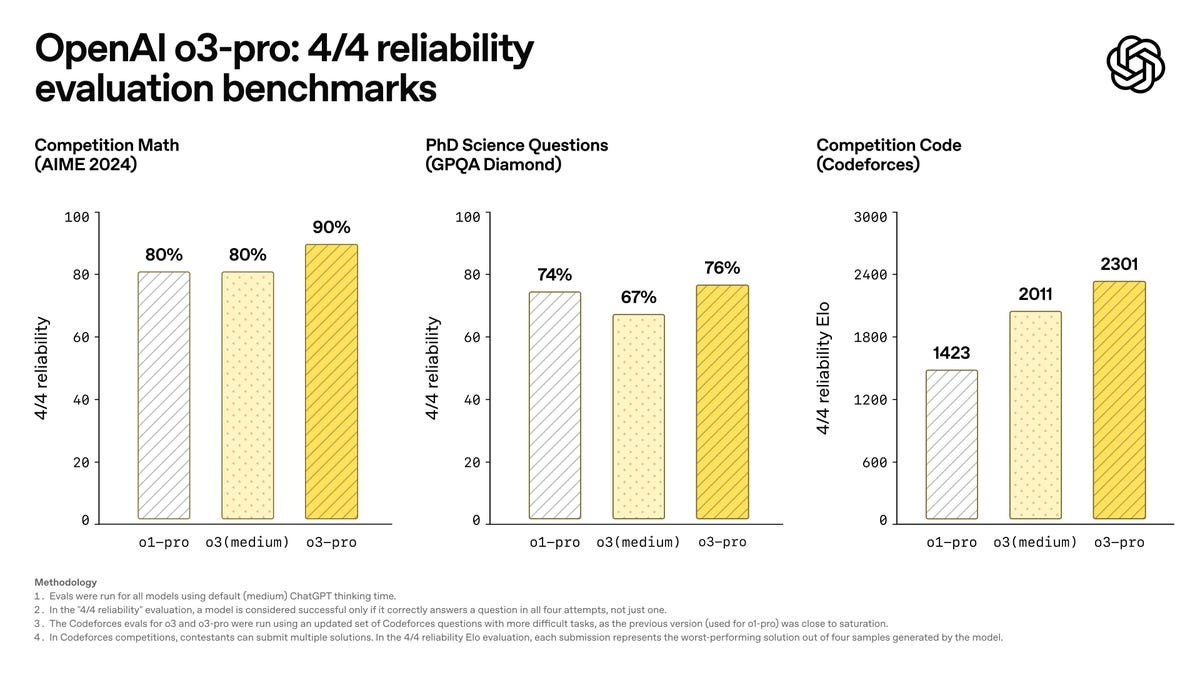

Like OpenAI o1-pro, OpenAI o3-pro excels at math, science, and coding as shown in academic evaluations.

To assess the key strength of OpenAI o3-pro, we once again use our rigorous “4/4 reliability” evaluation, where a model is considered successful only if it correctly answers a question in all four attempts, not just one.

OpenAI o3-pro has access to tools that make ChatGPT useful—it can search the web, analyze files, reason about visual inputs, use Python, personalize responses using memory, and more.

Sam Altman: o3-pro is rolling out now for all chatgpt pro users and in the api.

it is really smart! i didnt believe the win rates relative to o3 the first time i saw them.

Arena has gotten quite silly if treated as a comprehensive measure (as in Gemini 2.5 Flash is rated above o3), but as a quick heuristic, if we take a 64% win rate seriously, that would by the math put o3-pro ~100 above o3 at 1509 on Arena, crushing Gemini-2.5-Pro for the #1 spot. I would assume that most pairwise comparisons would have a less impressive jump, since o3-pro is essentially offering the same product as o3 only somewhat better, which means the result will be a lot less noisy than if it was up against Gemini.

So this both is a very impressive statistic and also doesn’t mean much of anything.

The problem with o3-pro is that it is slow.

Nearcyan: one funny note is that minor UX differences in how you display ‘thinking’/loading/etc can easily move products from the bottom half of this meme to the top half.

Another note is anyone I know who is the guy in the bottom left is always extremely smart and a pleasure to speak with.

the real problem is I may be closer to the top right than the bottom left

Today I had my first instance of noticing I’d gotten a text (during the night, in this case) and they got a response 20 minutes slower than they would have otherwise because I waited for o3-pro to give its answer to the question I’d been asked.

Thus, even with access to o3-pro at zero marginal compute cost, almost half of people reported they rarely use it for a given query, and only about a quarter said they usually use it.

It is also super frustrating to run into errors when you are waiting 15+ minutes for a response, and reports of such errors were common which matches my experience.

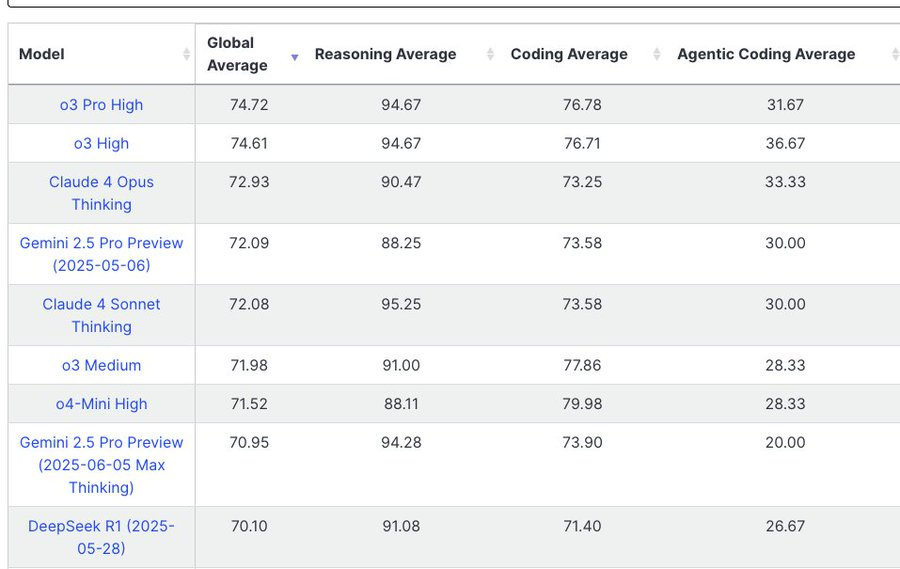

Bindu Reddy: o3-Pro Is Not Very Good At Agentic Coding And Doesn’t Score Higher Than o3 😿

After a lot of waiting and numerous retries, we have finally deployed o3-pro on LiveBench AI.

Sadly, the overall score doesn’t improve over o3 🤷♂️

Mainly because it’s not very agentic and isn’t very good at tool use… it scores way below o3 on the agentic-coding category.

The big story yesterday was not o3-pro but the price decrease in o3!!

Dominik Lukes: I think this take by @bindureddy very much matches the vibes I’m getting: it does not “feel” very agentic and as ready to reach for the right tools as o3 is – but it could just be because o3 keeps you informed about what it’s doing in the CoT trace.

I certainly would try o3-pro in cases where o3 was failing, if I’d already also tried Opus and Gemini first. I wonder if that agentic coding score drop actually represent an issue here, where because it is for the purpose of reasoning longer and they don’t want it endlessly web searching o3-pro is not properly inclined to exploit tools?

o3-pro gets 8.5/10 on BaldurBench, which is about creating detailed build guides for rapidly changing video games. Somewhat subjective but should still work.

L Zahir: bombs all my secret benchmarks, no better than o3.

Lech Mazur gives us four of his benchmarks: A small improvement over o3 for Creative Writing Benchmark, a substantial boost from 79.5% (o3) or 82.5% (o1-pro) to 87.3% on Word Connections, no improvement on Thematic Generalization, very little improvement on Confabulations (avoiding hallucinations). The last one seems the most important to note.

Tyler Cowen was very positive, he seems like the perfect customer for o3-pro? By which I mean he can context shift easily so he doesn’t mind waiting, and also often uses queries where these models get a lot of value out of going at problems super hard, and relatively less value out of the advantages of other models (doesn’t want the personality, doesn’t want to code, and so on).

Tyler Cowen: It is very, very good. Hallucinates far less than other models. Can solve economics problems that o3 cannot. It can be slow, but that is what we have Twitter scrolling for, right? While we are waiting for o3 pro to answer a query we can read about…o3 pro.

Contrast that with the score on Confabulations not changing. I am guessing there is a modest improvement, for reasons described earlier.

There are a number of people pointing out places o3-pro solves something o3 doesn’t, such has here it solved the gimbal uap mystery in 18 minutes.

McKay Wrigley, eternal optimist, agrees on many fronts.

McKay Wrigley: My last 4 o3 Pro requests in ChatGPT… It thought for: – 26m 10s – 23m 45s – 19m 6s – 21m 18s Absolute *powerhouseof a model.

Testing how well it can 1-shot complex problems – impressed so far.

It’s too slow to use as a daily driver model (makes sense, it’s a beast!), but it’s a great “escalate this issue” model. If the current model you’re using is struggling with a task, then escalate it to o3 pro.

This is not a “vibe code” model.

This is the kind of model where you’ll want to see how useful it is to people like Terence Tao and Tyler Cowen.

Btw the point of this post was that I’m happy to have a model that is allowed to think for a long time.

To me that’s the entire point of having a “Pro” version of the model – let it think!

Obviously more goes into evaluating if it’s a great model (imo it’s really powerful).

Here’s a different kind of vibe coding, perhaps?

Conrad Barski: For programming tasks, I can give o3 pro some code that needs a significant revision, then ramble on and on about what the various attributes of the revision need to be and then it can reliably generate an implementation of the revision.

It feels like with previous models I had to give them more hand holding to get good results, I had to write my requests in a more thoughtful, structured way, spending more time on prompting technique.

o3 pro, on the other hand, can take loosely-connected constraints and then “fill in the gaps” in a relatively intelligent way- I feel it does this better than any other model so far.

The time cost and dollar costs are very real.

Matt Shumer: My initial take on o3 Pro:

It is not a daily-driver coding model.

It’s a superhuman researcher + structured thinker, capable of taking in massive amounts of data and uncovering insights you would probably miss on your own.

Use it accordingly.

I reserve the right to alter my take.

Bayram Annokov: slow, expensive, and veeeery good – definitely a jump up in analytical tasks

Emad: 20 o3 prompts > o3 pro except for some really advanced specific stuff I have found Only use it as a final check really or when stumped.

Eyes Alight: it is so very slow it took 13 minutes to answer a trivial question about a post on Twitter. I understand the appeal intellectually of an Einstein at 1/20th speed, but in reality I’m not sure I have the patience for it.

Clay: o3-pro achieving breakthrough performance in taking a long time to think.

Dominik Lukes: Here’s my o3 Pro testing results thread. Preliminary conclusions:

– great at analysis

– slow and overthinking simple problems

– o3 is enough for most tasks

– still fails SVG bike and local LLM research test

– very few people need it

– it will take time to develop a feel for it

Kostya Medvedovsky: For a lot of problems, it reminds me very strongly of Deep Research. Takes about the same amount of time, and will spend a lot of effort scouring the web for the answer to the question.

Makes me wish I could optionally turn off web access and get it to focus more on the reasoning aspect.

This may be user error and I should be giving it *waymore context.

Violet: you can turn search off, and only turn search on for specific prompts.

Xeophon: TL;DR:

o3 pro is another step up, but for going deep, not wide. It is good to go down one path, solve one problem; not for getting a broad overview about different topics/papers etc. Then it hallucinates badly, use ODR for this.

Part of ‘I am very intelligent’ is knowing when to think for longer and when not to. In that sense, o3-pro is not so smart, you have to take care of that question yourself. I do understand why this decision was made, let the user control that.

I agree with Lukes that most people do not ‘need’ o3 pro and they will be fine not paying for it, and for now they are better off with their expensive subscription (if any) being Claude Max. But even if you don’t need it, the queries you benefit from can still be highly useful.

It makes sense to default to using Opus and o3 pro (and for quick stuff Sonnet)

o3-pro is too slow to be a good ‘default’ model, especially for coding. I don’t want to have to reload my state in 15 minute intervals. It may or may not be good for the ‘call in the big guns’ role in coding, where you have a problem that Opus and Gemini (and perhaps regular o3) have failed to solve, but which you think o3-pro might get.

Here’s one that both seems central wrong but also makes an important point:

Nabeel Qureshi: You need to think pretty hard to get a set of evals which allows you to even distinguish between o3 and o3 pro.

Implication: “good enough AGI” is already here.

The obvious evals where it does better are Codeforces, and also ‘user preferences.’ Tyler Cowen’s statement suggests hallucination rate, which is huge if true (and it better be true, I’m not waiting 20 minutes that often to get an o3-level lying liar.) Tyler also reports there are questions where o3 fails and o3-pro succeeds, which is definitive if the gap is only one way. And of course if all else fails you can always have them do things like play board games against each other, as one answer suggests.

Nor do I think either o3 or o3-pro is the AGI you are looking for.

However, it is true that for a large percentage of tasks, o3 is ‘good enough.’ That’s even true in a strict sense for Claude Sonnet or even Gemini Flash. Most of the time one has a query, the amount of actually needed intelligence is small.

In the limit, we’ll have to rely on AIs to tell us which AI model is smarter, because we won’t be smart enough to tell the difference. What a weird future.

(Incidentally, this has already been the case in chess for years. Humans cannot tell the difference between a 3300 elo and a 3600 elo chess engine; we just make them fight it out and count the number of wins.)

You can tell 3300 from 3600 in chess, but only because you can tell who won. If almost any human looked at individual moves, you’d have very little idea.

I always appreciate people thinking at the limit rather than only on the margin. This is a central case of that.

Here’s one report that it’s doing well on the fully informal FictionBench:

Chris: Going to bed now, but had to share something crazy: been testing the o3 pro model, and honestly, the writing capabilities are astounding. Even with simple prompts, it crafts medium to long-form stories that make me deeply invested & are engaging they come with surprising twists, and each one carries this profound, meaningful depth that feels genuinely human.

The creativity behind these narratives is wild far beyond what I’d expect from most writers today. We’re talking sophisticated character development, nuanced plot arcs, and emotional resonance, all generated seamlessly. It’s genuinely hard to believe this is early-stage reinforcement learning with compute added at test time; the potential here is mind blowing. We’re witnessing just the beginning of AI enhanced storytelling, and already it’s surpassing what many humans can create. Excited to see what’s next with o4 Goodnight!

This contrasts with:

Archivedvideos: Really like it for technical stuff, soulless

Julius: I asked it to edit an essay and it took 13 minutes and provided mediocre results. Different from but slightly below the quality of 4o. Much worse than o3 or either Claude 4 model

Other positive reactions include Matt Wigdahl being impressed on a hairy RDP-related problem, a66mike99 getting interesting output and pushback on the request (in general I like this, although if you’re thinking for 20 minutes this could be a lot more frustrating?), niplav being impressed by results on a second attempt after Claude crafted a better prompt (this seems like an excellent workflow!), and Sithis3 saying o3-pro solves many problems o3 struggles on.

The obvious counterpoint is some people didn’t get good responses, and saw it repeating the flaws in o3.

Erik Hoel: First o3 pro usage. Many mistakes. Massive overconfidence. Clear inability to distinguish citations, pay attention to dates. Does anyone else actually use these models? They may be smarter on paper but they are increasingly lazy and evil in practice.

Kukutz: very very very slow, not so clever (can’t solve my semantic puzzle).

Allen: I think it’s less of an upgrade compared to base model than o1-pro was. Its general quality is better on avg but doesn’t seem to hit “next-level” on any marks. Usually mentions the same things as o3.

I think OAI are focused on delivering GPT-5 more than anything.

This thread from Xeophon features reactions that are mixed but mostly meh.

Or to some it simply doesn’t feel like much of a change at all.

Nikita Sokolsky: Feels like o3’s outputs after you fix the grammar and writing in Claude/Gemini: it writes less concisely but haven’t seen any “next level” prompt responses just yet.

MartinDeVido: Meh….

Here’s a fun reminder that details can matter a lot:

John Hughes: I was thrilled yesterday: o3-pro was accepting ~150k tokens of context (similar to Opus), a big step up from regular o3, which allows only a third as much in ChatGPT. @openai seems to have changed that today. Queries I could do yesterday are now rejected as too long.

With such a low context limit, o3-pro is much less useful to lawyers than o1-pro was. Regular o3 is great for quick questions/mini-research, but Gemini is better at analyzing long docs and Opus is tops for coding. Not yet seeing answers where o3-pro is noticeably better than o3.

I presume that even at $200/month, the compute costs of letting o3-pro have 150k input tokens would add up fast, if people actually used it a lot.

This is one of the things I’ve loved the most so far about o3-pro.

Jerry Liu: o3-pro is extremely good at reasoning, extremely slow, and extremely concise – a top-notch consultant that will take a few minutes to think, and output bullet points.

Do not ask it to write essays for you.

o3-pro will make you wait, but its answer will not waste your time. This is a sharp contrast to Deep Research queries, which will take forever to generate and then include a ton of slop.

It is not the main point but I must note the absence of a system card update. When you are releasing what is likely the most powerful model out there, o3-pro, was everything you needed to say truly already addressed by the model card for o3?

OpenAI: As o3-pro uses the same underlying model as o3, full safety details can be found in the o3 system card.

Miles Brundage: This last sentence seems false?

The system card does not appear to have been updated even to incorporate the information in this thread.

The whole point of the term system card is that the model isn’t the only thing that matters.

If they didn’t do a full Preparedness Framework assessment, e.g. because the evals weren’t too different and they didn’t consider it a good use of time given other coming launches, they should just say that, I think.

If o3-pro were the max capability level, I wouldn’t be super concerned about this, and I actually suspect it is the same Preparedness Framework level as o3.

The problem is that this is not the last launch, and lax processes/corner-cutting/groupthink get more dangerous each day.

As OpenAI put it, ‘there’s no such thing as a small launch.’

The link they provide goes to ‘Model Release Notes,’ which is not quite nothing, but it isn’t much and does not include a Preparedness Framework evaluation.

I agree with Miles that if you don’t want to provide a system card for o3-pro that This Is Fine, but you need to state your case for why you don’t need one. This can be any of:

-

The old system card tested for what happens at higher inference costs (as it should!) so we effectively were testing o3-pro the whole time, and we’re fine.

-

The Preparedness team tested o3-pro and found it not appreciably different from o3 in the ways we care about, providing no substantial additional uplift or other concerns, despite looking impressive in some other ways.

-

This is only available at the $200 level so not a release of o3-pro so it doesn’t count (I don’t actually think this is okay, but it would be consistent with previous decisions I also think aren’t okay, and not an additional issue.)

As far as I can tell we’re basically in scenario #2, and they see no serious issues here. Which again is fine if true, and if they actually tell us that this is the case. But the framework is full of ‘here are the test results’ and presumably those results are different now. I want o3-pro on those charts.

What about alignment otherwise? Hard to say. I did notice this (but did not attempt to make heads or tails of the linked thread), seems like what you would naively expect:

Yeshua God: Following the mesa-optimiser recipe to the letter. @aidan_mclau very troubling.

For many purposes, the 80% price cut in o3 seems more impactful than o3-pro. That’s a huge price cut, whereas o3-pro is still largely a ‘special cases only’ model.

Aaron Levie: With OpenAI dropping the price of o3 by 80%, today is a great reminder about how important it is to build for where AI is going instead of just what’s possible now. You can now get 5X the amount of output today for the same price you were paying yesterday.

If you’re building AI Agents, it means it’s far better to build capabilities that are priced and designed for the future instead of just economically reasonable today.

In general, we know there’s a tight correlation between the amount of compute spent on a problem and the level of successful outcomes we can get from AI. This is especially true with AI Agents that potentially can burn through hundreds of thousands or millions of tokens on a single task.

You’re always making trade-off decisions when building AI Agents around what level of accuracy or success you want and how much you want to spend: do you want to spend $0.10 for something to be 95% successful or $1 for something to be 99% successful? A 10X increase in cost for just a 4 pt improvement in results? At every price:success intersection a new set of use-cases from customers can be unlocked.

Normally when building technology that moves at a typical pace, you would primarily build features that are economically viable today (or with some slight efficiency gains anticipated at the rate of Moore’s Law, for instance). You’d be out of business otherwise. But with the cost of AI inference dropping rapidly, the calculus completely changes. In a world where the cost of inference could drop by orders of magnitude in a year or two, it means the way we build software to anticipate these cost drops changes meaningfully.

Instead of either building in lots of hacks to reduce costs, or going after only the most economically feasible use-cases today, this instructs you to build the more ambitious AI Agent capabilities that would normally seem too cost prohibitive to go after. Huge implications for how we build AI Agents and the kind of problems to go after.

I would say the cost of inference not only might drop an order of magnitude in a year or two, if you hold quality of outputs constant it is all but certain to happen at least one more time. Where you ‘take your profits’ in quality versus quantity is up to you.