Congratulations, as always, to everyone who got to participate in the 2025 International Mathematical Olympiad, and especially to the gold and other medalists. Gautham Kamath highlights 11th grader Warren Bei, who in his 5th (!) IMO was one of five participants with a perfect 42/42 score, along with Ivan Chasovskikh, Satoshi Kano, Leyan Deng and Hengye Zhang.

Samuel Albanie: Massive respect to the students who solved P6.

Congratulations to Team USA, you did not ‘beat China’ but 2nd place is still awesome. Great job, China, you got us this time, three perfect scores is crazy.

You’ve all done a fantastic, amazingly hard thing, and as someone who tried hard to join you and only got as far as the [, year censored because oh man I am old] USAMO and would probably have gotten 0/45 on this IMO if I had taken it today, and know what it is like to practice for the USAMO in a room with multiple future IMO team members that must have thought I was an idiot, let me say: I am always in awe.

But that’s not important right now.

What matters is that Google and OpenAI have LLMs with gold medal performances, each scoring exactly the threshold of 35/42 by solving the first five of the six problems.

This is up from Google’s 28/42 performance last year, which was previously achieved with a longer time frame. The methods used by both are presented as being more general, whereas last year’s version was a more specialized effort.

The new scores were a 92nd percentile result at the event.

Google did this under official collaboration with the IMO, announced on Monday as per the IMO’s request. OpenAI did it on their own, so they announced a bit earlier, so we are taking their word on many details.

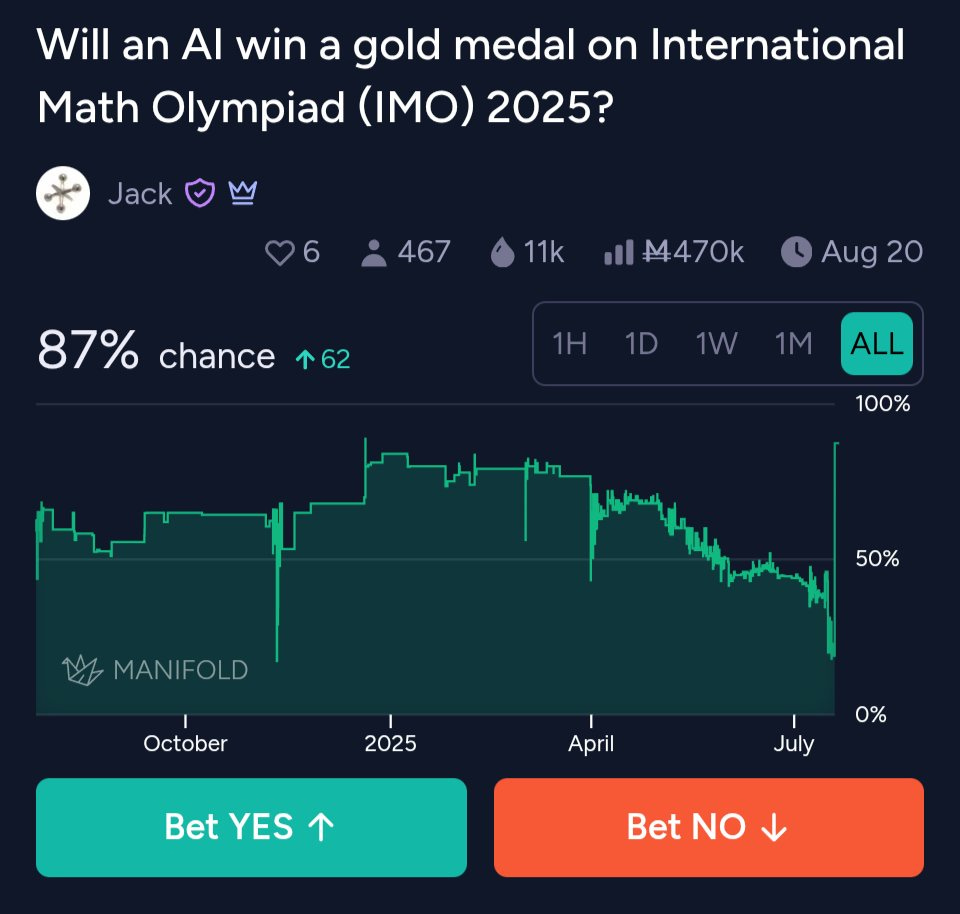

This was not expected. Prediction markets thought gold this year was unlikely.

What matters more is how they did it, with general purpose LLMs without tools, in ways that represent unexpected and large future gains in other reasoning as well.

The more I think about the details here, the more freaked out I get rather than less. This is a big deal. How big remains to be seen, as we lack details, and no one knows how much of this will generalize.

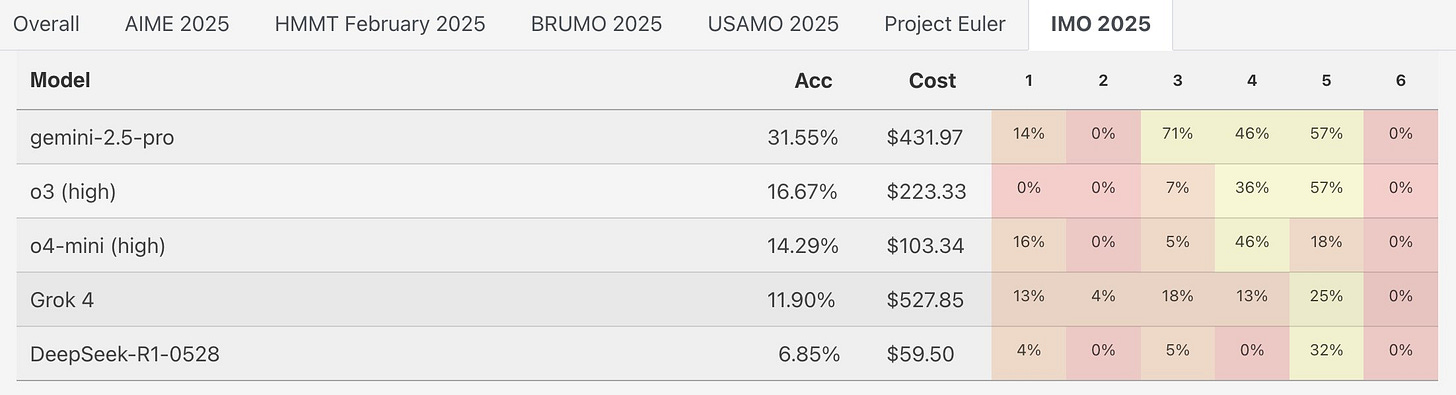

The IMO 2025 results quickly came in for released models.

Teortaxes: I sure jumped the gun calling Grok a next generation model.

It’s probably not *thatfar from Gemini, compute-wise, and not really close in diversity and rigor of post-training.

This was an early sign that problem 3 was easier than usual this year, and a strong performance by the release version of Gemini 2.5 Pro.

So this is how it started seven hours before OpenAI announced its result:

Jxmo (replying to Ravid): if they did well, you’d be complaining that they overfit.

Ravid Shwartz: That’s true, because they are 👽

Rohit: This isn’t a gotcha. Any problem that we fundamentally focus on deeply enough is one that AI will be able to solve. The question, as ever, is whether that solution is likely to carry over to other domains.

I disagree, I think this is a gotcha in the positive sense. People took ‘the AIs that weren’t aimed at this problem that are publicly released are only doing okay relative to the best humans, and have not proven themselves the best yet’ to be ‘look at the pathetic AIs,’ one day before we learned that, well, actually, in a way prediction markets did not expect.

I do think people need to update their models of the future.

Also, it’s kind of a full gotcha given this:

Lin Yang: 🚨 Olympiad math + AI:

We ran Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro on the fresh IMO 2025 problems. With careful prompting and pipeline design, it solved 5 out of 6 — remarkable for tasks demanding deep insight and creativity.

The model could win gold! 🥇

It would be non-trivial for non-math person to achieve the same score. We have spent some time to carefully check the solutions. Regardless, the prompts are very general and can be applied to other models. We will release an automatic agent soon.

Jun Wu: They added a lot of steps in order to solve 5 problems. They didn’t publish the details on how these steps were done beyond the concepts.

I don’t have time to investigate how ‘legit’ the Gemini 2.5 Pro solutions are, including in terms of how much you have to cheat to get them.

Advanced version of Gemini with Deep Think officially achieves gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad. Google’s solutions are here.

We achieved this year’s result using an advanced version of Gemini Deep Think – an enhanced reasoning mode for complex problems that incorporates some of our latest research techniques, including parallel thinking. This setup enables the model to simultaneously explore and combine multiple possible solutions before giving a final answer, rather than pursuing a single, linear chain of thought.

To make the most of the reasoning capabilities of Deep Think, we additionally trained this version of Gemini on novel reinforcement learning techniques that can leverage more multi-step reasoning, problem-solving and theorem-proving data. We also provided Gemini with access to a curated corpus of high-quality solutions to mathematics problems, and added some general hints and tips on how to approach IMO problems to its instructions.

We will be making a version of this Deep Think model available to a set of trusted testers, including mathematicians, before rolling it out to Google AI Ultra subscribers.

Google’s answers were even in nice form.

IMO President Dr. Gregor Dolinar: We can confirm that Google DeepMind has reached the much-desired milestone, earning 35 out of a possible 42 points — a gold medal score. Their solutions were astonishing in many respects. IMO graders found them to be clear, precise and most of them easy to follow.

Colin Fraser: has anyone actually read these LLM IMO proofs? I read one of the Google ones and it’s good. I find the OAI version of the same one impenetrable. The Google one is also kind of hard to read but possible.

Ernest Davis (6th in US Math Olympiad once, just short of the IMO): Second: The proofs produced by DM-IMO and by every single earlier LLM, whether correct or incorrect, are written in a smooth, elegant style. They could be cut and pasted into a journal article or into a textbook with little or no editing. The worst you can say of them is that they are sometimes verbose.

By contrast, OpenAI-IMO writes proofs in the style of an informal spoken presentation who is not very practiced or competent at giving informal presentations, and regularly mutters reassurances to themselves that they’re on the right rack.

Miles Brundage: OAI one got RL’d to within an inch of its life.

What else did they say about how they did this?

DeepMind: With Deep Think, an enhanced reasoning mode, our model could simultaneously explore and combine multiple possible solutions before giving definitive answers.

We also trained it on RL techniques that use more multi-step reasoning, problem-solving and theorem-proving data.

Finally, we pushed this version of Gemini further by giving it:

🔘 More thinking time

🔘 Access to a set of high-quality solutions to previous problems

🔘 General hints and tips on how to approach IMO problems

That sounds mostly rather general. There’s some specialized IMO context, but orders of magnitude less than what IMO competitors devote to this.

Elon Musk: While a notable milestone, this is already borderline trivial for AI.

Um, Elon, no, and I remind you that Grok 4 got 11.9%. Which for a human would be super impressive, but seriously, borderline trivial?

Noam Brown (OpenAI): Congrats to the GDM team on their IMO result! I think their parallel success highlights how fast AI progress is. Their approach was a bit different than ours, but I think that shows there are many research directions for further progress.

OpenAI claimed its victory first, right after the closing ceremony and before the party, whereas Google DeepMind waited to announce until the following Monday.

The most impressive thing about OpenAI’s result is that they claim this is not an IMO-specific model, and that it uses only general-purpose techniques.

Alexander Wei (OpenAI): I’m excited to share that our latest @OpenAI experimental reasoning LLM has achieved a longstanding grand challenge in AI: gold medal-level performance on the world’s most prestigious math competition—the International Math Olympiad (IMO).

We evaluated our models on the 2025 IMO problems under the same rules as human contestants: two 4.5 hour exam sessions, no tools or internet, reading the official problem statements, and writing natural language proofs.

Why is this a big deal? First, IMO problems demand a new level of sustained creative thinking compared to past benchmarks. In reasoning time horizon, we’ve now progressed from GSM8K (~0.1 min for top humans) → MATH benchmark (~1 min) → AIME (~10 mins) → IMO (~100 mins).

Second, IMO submissions are hard-to-verify, multi-page proofs. Progress here calls for going beyond the RL paradigm of clear-cut, verifiable rewards. By doing so, we’ve obtained a model that can craft intricate, watertight arguments at the level of human mathematicians.

Besides the result itself, I am excited about our approach: We reach this capability level not via narrow, task-specific methodology, but by breaking new ground in general-purpose reinforcement learning and test-time compute scaling.

In our evaluation, the model solved 5 of the 6 problems on the 2025 IMO. For each problem, three former IMO medalists independently graded the model’s submitted proof, with scores finalized after unanimous consensus. The model earned 35/42 points in total, enough for gold! 🥇

HUGE congratulations to the team—@SherylHsu02, @polynoamial, and the many giants whose shoulders we stood on—for turning this crazy dream into reality! I am lucky I get to spend late nights and early mornings working alongside the very best.

Btw, we are releasing GPT-5 soon, and we’re excited for you to try it. But just to be clear: the IMO gold LLM is an experimental research model. We don’t plan to release anything with this level of math capability for several months.

Still—this underscores how fast AI has advanced in recent years. In 2021, my PhD advisor @JacobSteinhardt had me forecast AI math progress by July 2025. I predicted 30% on the MATH benchmark (and thought everyone else was too optimistic). Instead, we have IMO gold.

If you want to take a look, here are the model’s solutions to the 2025 IMO problems! The model solved P1 through P5; it did not produce a solution for P6. (Apologies in advance for its … distinct style—it is very much an experimental model 😅)

Lastly, we’d like to congratulate all the participants of the 2025 IMO on their achievement! We are proud to have many past IMO participants at @OpenAI and recognize that these are some of the brightest young minds of the future.

Noam Brown (OpenAI): Today, we at @OpenAI achieved a milestone that many considered years away: gold medal-level performance on the 2025 IMO with a general reasoning LLM—under the same time limits as humans, without tools. As remarkable as that sounds, it’s even more significant than the headline.

Typically for these AI results, like in Go/Dota/Poker/Diplomacy, researchers spend years making an AI that masters one narrow domain and does little else. But this isn’t an IMO-specific model. It’s a reasoning LLM that incorporates new experimental general-purpose techniques.

So what’s different? We developed new techniques that make LLMs a lot better at hard-to-verify tasks. IMO problems were the perfect challenge for this: proofs are pages long and take experts hours to grade. Compare that to AIME, where answers are simply an integer from 0 to 999.

Jacques: Most important part of the IMO Gold achievement. Were you surprised by this? Did you not update all the way to avoid likelihood of surprise?

Indeed. Purely getting the gold medal is surprising but not that big a deal. The way they got the result, assuming they’re reporting accurately? That’s a really big deal.

Noam Brown (resuming): Also this model thinks for a *longtime. o1 thought for seconds. Deep Research for minutes. This one thinks for hours. Importantly, it’s also more efficient with its thinking. And there’s a lot of room to push the test-time compute and efficiency further.

…

Importantly, I think we’re close to AI substantially contributing to scientific discovery. There’s a big difference between AI slightly below top human performance vs slightly above.

This was a small team effort led by @alexwei_. He took a research idea few believed in and used it to achieve a result fewer thought possible. This also wouldn’t be possible without years of research+engineering from many at @OpenAI and the wider AI community.

Tifa Chen: Last night we IMO tonight we party.

What about Problem 6? Did the programs submit incorrect solutions?

Note that if you are maximizing, then when time runs out if you have anything at all then yes you do submit the best incorrect solution you have, because you might get you partial credit, although this rarely works out.

Daniel Litt: One piece of info that seems important to me in terms of forecasting usefulness of new AI models for mathematics: did the gold-medal-winning models, which did not solve IMO problem 6, submit incorrect answers for it?

Alexander Wei: On IMO P6 (without going into too much detail about our setup), the model “knew” it didn’t have a correct solution. The model knowing when it didn’t know was one of the early signs of life that made us excited about the underlying research direction!

If one person gets to say ‘Not So Fast’ about this sort of thing, Tao is that one person.

It is entirely fair to say that if you don’t disclose conditions in advance, and definitely if you don’t disclose conditions after the fact, it is difficult to know exactly what to make of the result. Tao’s objections are valid.

Terence Tao: It is tempting to view the capability of current AI technology as a singular quantity: either a given task X is within the ability of current tools, or it is not. However, there is in fact a very wide spread in capability (several orders of magnitude) depending on what resources and assistance gives the tool, and how one reports their results.

One can illustrate this with a human metaphor. I will use the recently concluded International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) as an example. Here, the format is that each country fields a team of six human contestants (high school students), led by a team leader (often a professional mathematician). Over the course of two days, each contestant is given four and a half hours on each day to solve three difficult mathematical problems, given only pen and paper. No communication between contestants (or with the team leader) during this period is permitted, although the contestants can ask the invigilators for clarification on the wording of the problems. The team leader advocates for the students in front of the IMO jury during the grading process, but is not involved in the IMO examination directly.

The IMO is widely regarded as a highly selective measure of mathematical achievement for a high school student to be able to score well enough to receive a medal, particularly a gold medal or a perfect score; this year the threshold for the gold was 35/42, which corresponds to answering five of the six questions perfectly. Even answering one question perfectly merits an “honorable mention”.

But consider what happens to the difficulty level of the Olympiad if we alter the format in various ways, such as the following:

-

One gives the students several days to complete each question, rather than four and half hours for three questions. (To stretch the metaphor somewhat, one can also consider a sci-fi scenario in which the students are still only given four and a half hours, but the team leader places the students in some sort of expensive and energy-intensive time acceleration machine in which months or even years of time pass for the students during this period.)

-

Before the exam starts, the team leader rewrites the questions in a format that the students find easier to work with.

-

The team leader gives the students unlimited access to calculators, computer algebra packages, formal proof assistants, textbooks, or the ability to search the internet.

-

The team leader has the six student team work on the same problem simultaneously, communicating with each other on their partial progress and reported dead ends.

-

The team leader gives the students prompts in the direction of favorable approaches, and intervenes if one of the students is spending too much time on a direction that they know to be unlikely to succeed.

-

Each of the six students on the team submit solutions to the team leader, who then selects only the “best” solution for each question to submit to the competition, discarding the rest.

-

If none of the students on the team obtains a satisfactory solution, the team leader does not submit any solution at all, and silently withdraws from the competition without their participation ever being noted.

In each of these formats, the submitted solutions are still technically generated by the high school contestants, rather than the team leader. However, the reported success rate of the students on the competition can be dramatically affected by such changes of format; a student or team of students who might not even always reach bronze medal performance if taking the competition under standard test conditions might instead reach reliable gold medal performance under some of the modified formats indicated above.

So, in the absence of a controlled test methodology that was not self-selected by the competing teams, one should be wary of making overly simplistic apples-to-apples comparisons between the performance of various AI models on competitions such as the IMO, or between such models and the human contestants.

Related to this, I will not be commenting on any self-reported AI competition performance results for which the methodology was not disclosed in advance of the competition.

EDIT: In particular, the above comments are not specific to any single result of this nature.

The catch is that this is about grading the horse’s grammar, as opposed to the observation that the horse can talk and rather intelligently and with rapidly improving performance at that.

Thus, while the objections are valid, as long as we know the AIs had no access to outside tools or to the internet (which is confirmed), we should seek the answers to these other questions but the concerns primarily matter for comparisons between models, and within a reasonably narro (in the grand scheme of things) band of capabilities.

I also would note that if OpenAI did essentially do the ‘team thinks in parallel’ thing where it had multiple inference processes running simultaneously on multiple computers, well, that is something AIs can do in the real world, and this seems entirely fair for our purposes the same way humans can fire multiple neurons at once. It’s totally fair to also want a limited-compute or one-thread category or what not, but that’s not important right now.

To use Tao’s metaphor, if you took 99.99% of high school students, you could fully and simultaneously apply all these interventions other than formal proof assistants and internet searches or hints so clear they give you the first point on a question, and you still almost always get zero.

Nat McAleese: 17 M U.S. teens grades 9-12, ~5 US IMO golds in practice but ~20 kids at gold-level. So IMO gold is one-in-a-million math talent (for 18 year olds; but I bet next Putnam falls too). 99.9999th percentile.

As a former not only math competitor but also Magic: The Gathering competitor, absolutely all these details matter for competitions, and I respect the hell out of getting all of those details right – I just don’t think that, in terms of takeaways, they change the answer much here.

In other words? Not Not So Fast. So Fast.

OpenAI chose not to officially collaborate with the IMO. They announced their result after the IMO closing ceremony and prior to the IMO 2025 closing party. Those who did collaborate agreed to wait until the following Monday, which was when Google announced. By going first, OpenAI largely stole the spotlight on this from Google, yet another case of Google Failing Marketing Forever.

A question that was debated is, did OpenAI do something wrong here?

Mikhail Samin claimed that they did, and put their hype and clout ahead of the kids celebrating their achievements against the wishes of the IMO.

OpenAI’s Noam Brown replied that they waited until after the closing ceremony exactly to avoid stealing the spotlight. He said he was the only person at OpenAI to speak to anyone at the IMO, and that person only requested waiting until after the ceremony, so that is what OpenAI did.

Not collaborating with the IMO was a choice that OpenAI made.

Mikhail Samin: AI companies that chose to cooperate with the IMO on assessment of the performance of their models had in-person meetings with IMO people on July 16. It was agreed there that announcements of AI achievements should be made on 28 July or later.

A quote from someone involved: “I certainly expect that if OpenAI had contacted the IMO in advance and expressed interest in cooperating in the assessment of their work, they would have been able to be included in that meeting, so I suppose that unless there was a major miscommunication somewhere, they effectively ended up choosing, by default or otherwise, not to cooperate with the IMO on this, and so not to be aware of what ground rules might have been agreed by those who did cooperate.”

Demis Hassabis (CEO DeepMind): Btw as an aside, we didn’t announce on Friday because we respected the IMO Board’s original request that all AI labs share their results only after the official results had been verified by independent experts & the students had rightfully received the acclamation they deserved.

We’ve now been given permission to share our results and are pleased to have been part of the inaugural cohort to have our model results officially graded and certified by IMO coordinators and experts, receiving the first official gold-level performance grading for an AI system!

Noam Brown: ~2 months ago, the IMO emailed us about participating in a formal (Lean) version of the IMO. We’ve been focused on general reasoning in natural language without the constraints of Lean, so we declined. We were never approached about a natural language math option.

Over the past several months, we made a lot of progress on general reasoning. This involved collecting, curating, and training on high-quality math data, which will also go into future models. In our IMO eval we did not use RAG or any tools.

Before we shared our results, we spoke with an IMO board member, who asked us to wait until after the award ceremony to make it public, a request we happily honored.

We had each submitted proof graded by 3 external IMO medalists and there was unanimous consensus on correctness. We have also posted the proofs publicly so that anyone can verify correctness.

Jasper: DeepMind got a gold medal at the IMO on Friday afternoon. But they had to wait for marketing to approve the tweet — until Monday. @OpenAI shared theirs first at 1am on Saturday and stole the spotlight.

In this game, speed > bureaucracy. Miss the moment, lose the narrative.

Clarification: I’ve been told by someone at Google that their IMO results are still being verified internally. Once that’s done, they plan to share them officially—curious to see their approach. Another source mentioned that the IMO committee asked not to publicly discuss AI involvement within a week after the closing ceremony. Things just got a bit more interesting.

Daniel Eth: “In this game, speed > bureaucracy. Miss the moment, lose the narrative.” Honestly, disagree. If GDM beats OpenAI, then the narrative will shift once that’s public.

I have reflected on this. It is not the main thing, the results are the main thing. I do think that on reflection while OpenAI did not break any agreements or their word, and strictly speaking they do not owe the IMO or the kids anything, and this presumably net increased the focus on the kids, this still does represent a meaningful failure to properly honor the competition and process, as well as offering us the proper opportunities for verification, and they should have known that this was the case. I do get that this was a small team’s last minute effort, which makes me more understanding, but it’s still not great.

Fig Spirit: then again, assuming Myers is correct about his impression of the “general coordinator view”, seems like the kind of thing that OpenAI could have known about *ifthey cared, no? by e.g. talking to the right people at the IMO… which imo is not asking much! and looks like others did?

Thus, I was careful to wait to write this until after Google’s results were announced, and have placed Google’s announcement before OpenAI’s in this post, even though due to claimed details by OpenAI I do think their achievement here is likely the more meaningful one. Perhaps that is simply Google failing marketing again and failing to share details.

Ultimately, the reason OpenAI stole my spotlight is that it harkens something general and new in a way that Google’s announcement doesn’t.

With Google sharing its results I don’t want to wait any longer, but note Harmonic?

Harmonic Math: This past week, Harmonic had the opportunity to represent our advanced mathematical reasoning model, Aristotle, at the International Mathematics Olympiad – the most prestigious mathematics competition in the world.

To uphold the sanctity of the student competition, the IMO Board has asked us, along with the other leading AI companies that participated, to hold on releasing our results until July 28th.

So please join us live on @X next Monday, July 28th at 3PM PT and hear from our CEO @tachim and Executive Chairman @vladtenev about the advent of mathematical superintelligence (and maybe a few surprises along the way).

This would be a weird flex if they didn’t also get gold, although it looks like they would have done it in a less general and thus less ultimately interesting way. On the flip side, they are not a big lab like Google or OpenAI, so that’s pretty impressive.

I think the failure to expect this was largely a mistake, but Manifold tells a clear story:

Andrew Curran: OpenAI’s new model has achieved gold level at the International Math Olympiad in a stunning result. It is a reasoning model that incorporates new experimental general-purpose techniques. This has happened much sooner than was predicted by most experts.

Noam Brown (OpenAI): When you work at a frontier lab, you usually know where frontier capabilities are months before anyone else. But this result is brand new, using recently developed techniques. It was a surprise even to many researchers at OpenAI. Today, everyone gets to see where the frontier is.

Peter Wildeford: AI progress comes at you fast.

JGalt Tweets: When will an AI win a Gold Medal in the International Math Olympiad? Median predicted date over time

July 2021: 2043 (22 years away)

July 2022: 2029 (7 years away)

July 2023: 2028 (5 years away)

July 2024: 2026 (2 years away)

Final result, July 2025: 2025 (now). Buckle up, Dorothy.

Some people did expect it, some of whom offered caveats.

Greg Burnham: Pretty happy with how my predictions are holding up.

5/6 was the gold medal threshold this year. OAI’s “experimental reasoning LLM” got that exactly, failing only to solve the one hard combinatorics problem, P6.

My advice remains: look beyond the medal.

Now, this is an LLM, not AlphaProof. That means LLMs have improved at proofs. I didn’t expect that so soon.

Though, FWIW, P3 is a bit of an outlier this year, at least for humans: over 15% of humans got it, higher than any P3 in the last 10 years.

But “the big one” remains whether the AI solutions show qualitatively creative problem-solving.

LLMs could already grind out “low insight” sol’ns to hard AIME problems. If OAI found a way to train them do that for olympiad proof-based problems too, that’s new, but less exciting.

So, clear progress, but not *toosurprising. I’ll keep my takes tempered until looking at the AI solutions in depth, which I hope to do soon! Above excerpts from my preregistered take on the IMO here.

Mikhail Samin: As someone who bet back in 2023 that that it’s >70% likely AI will get an IMO gold medal by 2027:

the IMO markets have been incredibly underpriced, especially for the past year.

(Sadly, another prediction I’ve been >70% confident about is that AI will literally kill everyone.)

The AIs took the IMO under the same time limits as the humans, and success was highly valued, so it is no surprise that they used parallel inference to get more done within that time frame, trading efficiency for speed.

Andrew Curran: These agentic teams based models like Grok Heavy, the Gemini Deep Think that just won gold, and the next gen from OpenAI are all going to use about fifteen times more tokens than current systems. This is why Pro plans are north of $200. Essentially; Jensen wins again.

[from June 14]: Claude Opus, coordinating four instances of Sonnet as a team, used about 15 times more tokens than normal. (90% performance boost) Jensen has mentioned similar numbers on stage recently. GPT-5 is rumored to be agentic teams based. The demand for compute will continue to increase.

Arthur B: IMO gold is super impressive.

I just want to register a prediction, I’m 80% confident the inference run cost over $1M in compute.

Mostly because if they could do it for $1M they would, and they would be able to do it for $1M before they can do it for less.

Jerry Tworek (OpenAI): I’m so limited by compute you wouldn’t believe it. Stargate can’t finish soon enough.

Sure, you solved this particular problem, but that would never generalize, right? That part is the same hype as always?

Near Cyan: you wont believe how smart our new frontier llm is. it repeatedly samples from the data manifold just like our last one. but this time we gave it new data to cover a past blindspot. watch in awe as we now sample from a slightly different area of the data manifold.

there may lay a prize at the end of the hyperdimensioanl checkered rainbow, but it’s likely not what you think it is.

i really thought someone would have done something original by now. of course, if anything was ~truly~ cooking, it shouldn’t be something i’d know about… but the years continue to pass

and, right right we have to finish *this phaseso that we have the pre-requisites. and yet.

David Holz (CEO MidJourney): noooo money can’t be dumb it’s so green.

Near Cyan: it is for now! but some of it may turn a dark crimson surprisingly quickly.

Nico: What do you make of [the OpenAI model knowing it didn’t have a correct solution to problem 6]? Sounds pretty important.

Near Cyan: seems cool i bet they have some great data.

A grand tradition is:

-

AI can do a set of things [X] better than humans, but not a set of things [Y].

-

People say [X] and [Y] are distinct because Moravec’s Paradox and so on.

-

AI lab announces that [Z], previously in [Y], is now in [X].

-

People move [Z] from [Y] to [X] and then repeat that this distinct category of things [Y] exists because Moravec’s Paradox, that one task was simply miscategorized before, so it’s fine.

Or: AI can do the things it can do, and can’t do the things it can’t do, they’re hard.

Yuchen Jin: OpenAI and DeepMind models winning IMO golds is super cool, but not surprising if you remember AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol.

What’s easy for AI can be hard for humans, and vice versa. That’s Moravec’s Paradox.

So yes, AI can win math gold medals and beat humans in competitive coding contests. But ask it to act like a competent “intern” across a multi-step project without messing things up? Still a long way to go.

To get there, models need longer context windows, far less hallucination (a single one can derail a multi-step task), and likely a new learning paradigm. RL with a single scalar +1/-1 reward at the end of a long trajectory just isn’t informative enough to drive actual learning.

An oldie but a goodie:

Colin Fraser: Can an LLM make a good IMO problem

Posting before someone else does

I mean, it probably can’t even do real math, right?

Kevin Buzzard (Mathematician, Imperial College): I certainly don’t agree that machines which can solve IMO problems will be useful for mathematicians doing research, in the same way that when I arrived in Cambridge UK as an undergraduate clutching my IMO gold medal I was in no position to help any of the research mathematicians there.

It is still entirely unclear whether things will scale from machines being able to do mathematics which can be solved using high school techniques to machines being able to help with mathematics which can only be solved by having a deep understanding of modern research ideas.

This is a big open question right now.

Hehe: What most people don’t realize is that IMO (and IOI, though to a different extent) aren’t particularly hard. They’re aimed at high schoolers, so anyone with decent uni education should be able to solve most of them.

Daniel Litt: I’m sorry, this is nonsense. Vast majority of strong math majors can’t do 5/6 IMO problems. It’s a specific skill that getting a math major doesn’t really train you for.

So yes, we still do not know for sure if being able to do [X] will extend to doing [Y], either with the same model or with a future different model, and [X] and [Y] are distinct skills such that the humans who do [X] cannot yet do [Y] and training humans to do [Y] does not give them the ability to do [X]. However please try to think ahead.

Daniel Litt: An AI tool that gets gold on the IMO is obviously immensely impressive. Does it mean math is “solved”? Is an AI-generated proof of the Riemann hypothesis clearly on the horizon? Obviously not.

Worth keeping timescales in mind here: IMO competitors spend an average of 1.5 hrs on each problem. High-quality math research, by contrast, takes month or years.

What are the obstructions to AI performing high-quality autonomous math research? I don’t claim to know for sure, but I think they include many of the same obstructions that prevent it from doing many jobs:

Long context, long-term planning, consistency, unclear rewards, lack of training data, etc.

It’s possible that some or all of these will be solved soon (or have been solved) but I think it’s worth being cautious about over-indexing on recent (amazing) progress.

To briefly expand on the point about timescales: one recent paper I wrote solved a problem I’ve been thinking about since 2017. Another was 94 pages of extremely densely-written math, aimed at experts.

We don’t know much yet about how the best internal models work, but I don’t think it’s clear that getting capabilities of that level is “only” an engineering problem. That said, I do think it’s pretty likely that many or all of these issues will be solved within the span of my mathematics career.

That is all entirely fair. An IMO problem is measured in hours, not months, and is bounded in important ways. That is exactly the paradigm of METR, and the one being talked about by Noam Brown and Alexander Wei, that we have now made the move from 10 minute problems to 100 minute problems.

That does not mean we can yet solve 10,000 minute or 1 million minute problems, but why would you expect the scaling to stop here? As I discussed in the debates over AI 2027, it makes sense to think that these orders of magnitude start to get easier rather than harder once you get into longer problems. If you can do 100 minute problems that doesn’t mean you can easily go to 1000 or a million, but if you can go 1 million, I bet you can probably do 1 billion without fundamentally changing things that much, if you actually have that kind of time. At some point your timeline is ‘indefinite’ or ‘well, how much time and compute have you got?’

David White: the openai IMO news hit me pretty heavy this weekend.

i’m still in the acute phase of the impact, i think.

i consider myself a professional mathematician (a characterization some actual professional mathematicians might take issue with, but my party my rules) and i don’t think i can answer a single imo question.

ok, yes, imo is its own little athletic subsection of math for which i have not trained, etc. etc., but. if i meet someone in the wild who has an IMO gold, i immediately update to “this person is much better at math than i am”

now a bunch of robots can do it. as someone who has a lot of their identity and their actual life built around “is good at math,” it’s a gut punch. it’s a kind of dying.

like, one day you discover you can talk to dogs. it’s fun and interesting so you do it more, learning the intricacies of their language and their deepest customs. you learn other people are surprised by what you can do. you have never quite fit in, but you learn people appreciate your ability and want you around to help them. the dogs appreciate you too, the only biped who really gets it. you assemble for yourself a kind of belonging. then one day you wake up and the universal dog translator is for sale at walmart for $4.99.

the IMO result isn’t news, exactly. in fact, if you look at the METR agent task length over time plot, i think agents being able to solve ~ 1.5 hour problems is coming right on time. so in some way we should not be surprised. and indeed, it appears multiple companies have achieved the same result. it’s just… the rising tide rising as fast as it has been rising.

of course, grief for my personal identity as a mathematician (and/or productive member of society) is the smallest part of this story

multiply that grief out by *everymathematician, by every coder, maybe every knowledge worker, every artist… over the next few years… it’s a slightly bigger story

and of course, beyond that, there is the fear of actual death, which perhaps i’ll go into more later.

this package — grief for relevance, grief for life, grief for what i have known — isn’t unique to the ai age or anything like that. i think it is a standard thing as one appreaches end of career or end of life. it just might be that that is coming a bit sooner for many of us, all at once.

i wonder if we are ready

I am very confident we are not ready. If we are fortunate we might survive, but we definitely are not ready.

I grade this as minus one million points for asking the wrong questions.

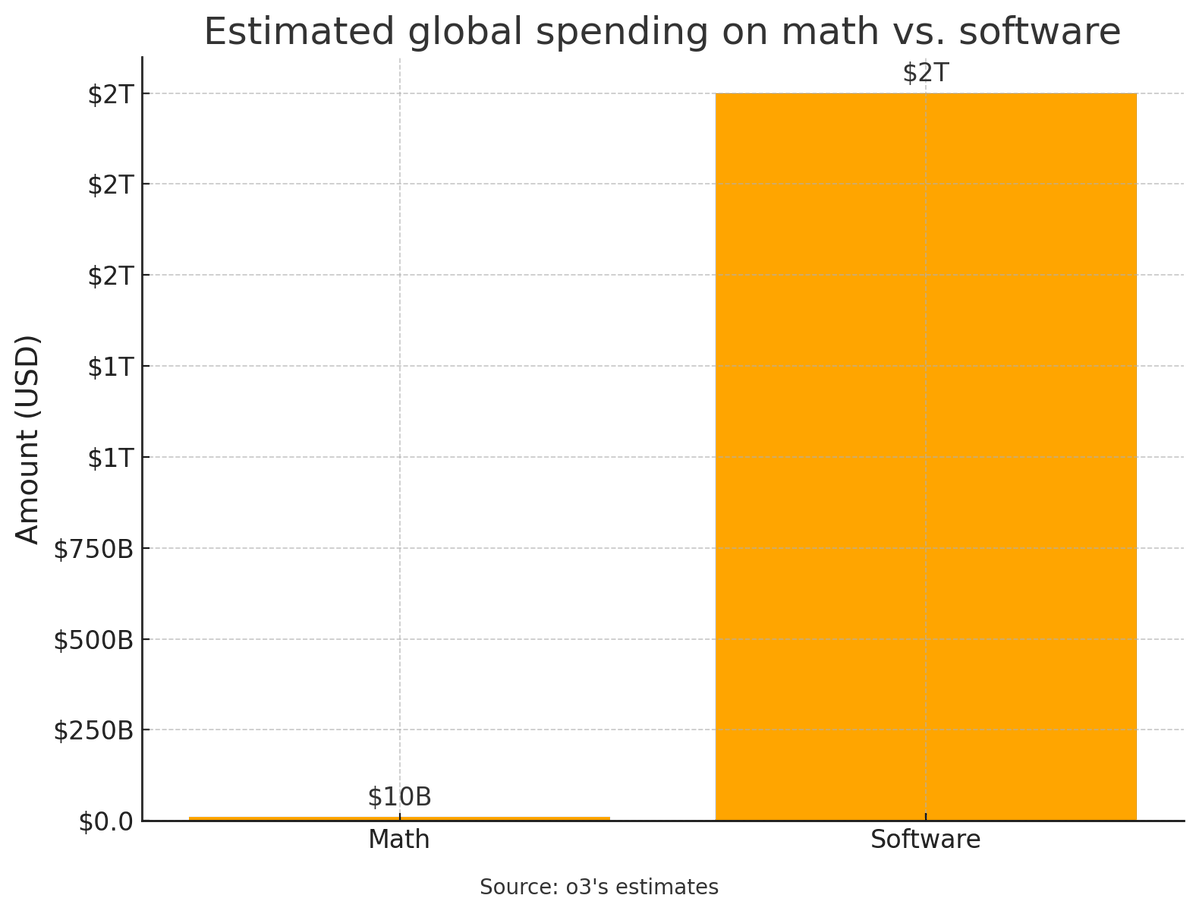

Mechanize: Automating math would generate less than 1% as much value as automating software engineering.

Perhaps AI labs should focus less on chasing gold medals and focus more on the hard problem of automating SWE.

T11s: this is pretty reductionist? innovations in math uniquely enable lots of software (eg cryptography made ecommerce possible)

Deedy: Quant trading is a lot of math and accounts for $50-100B in revenue.

Never confuse costs and benefits #RulesForLife, and never reason from a price change.

(This defines ‘math’ rather narrowly as advanced Real Math that mathematicians and maybe quants and other professionals do, not the kind of math that underlies absolutely everything we do all day, since Fake Math is already mostly automated.)

The value of automating is not determined by how much we spent on it before it got automated. The value is determined by how much additional value we get out of something when we automate it, which might involve a lot more production and very diffuse benefits.

Back in February 2022, Eliezer Yudkowsky bet with Paul Christiano about IMO performance by 2025. The results were not super clear cut if you look at the details, as Christiano was in large part doubting that the hardest problem would be solved and indeed the hardest problem was #6 and was not solved, but a gold medal was still achieved.

So I think we have Paul at <8%, Eliezer at >16% for AI made before the IMO is able to get a gold (under time controls etc. of grand challenge) in one of 2022-2025.

Separately, we have Paul at <4% of an AI able to solve the "hardest" problem under the same conditions.

…

How [I, Paul, would] update

The informative:

-

I think the IMO challenge would be significant direct evidence that powerful AI would be sooner, or at least would be technologically possible sooner. I think this would be fairly significant evidence, perhaps pushing my 2040 TAI [transformational AI] probability up from 25% to 40% or something like that.

-

I think this would be significant evidence that takeoff will be limited by sociological facts and engineering effort rather than a slow march of smooth ML scaling. Maybe I’d move from a 30% chance of hard takeoff to a 50% chance of hard takeoff.

-

If Eliezer wins, he gets 1 bit of epistemic credit. These kinds of updates are slow going, and it would be better if we had a bigger portfolio of bets, but I’ll take what we can get.

-

This would be some update for Eliezer’s view that “the future is hard to predict.” I think we have clear enough pictures of the future that we have the right to be surprised by an IMO challenge win; if I’m wrong about that then it’s general evidence my error bars are too narrow.

If an AI wins a gold on some but not all of those years, without being able to solve the hardest problems, then my update will be somewhat more limited but in the same direction.

At this point, we have a lot of people who have updated far past 40% chance of transformational AI by 2040 and have 40% for dates like 2029.

If we take all of OpenAI’s statements at face value, think about what they actually did.

Sam Altman: we achieved gold medal level performance on the 2025 IMO competition with a general-purpose reasoning system! to emphasize, this is an LLM doing math and not a specific formal math system; it is part of our main push towards general intelligence.

when we first started openai, this was a dream but not one that felt very realistic to us; it is a significant marker of how far AI has come over the past decade.

we are releasing GPT-5 soon but want to set accurate expectations: this is an experimental model that incorporates new research techniques we will use in future models. we think you will love GPT-5, but we don’t plan to release a model with IMO gold level of capability for many months.

Sheryl Hsu (OpenAI): Watching the model solve these IMO problems and achieve gold-level performance was magical.

The model solves these problems without tools like lean or coding, it just uses natural language, and also only has 4.5 hours. We see the model reason at a very high level – trying out different strategies, making observations from examples, and testing hypothesis.

It’s crazy how we’ve gone from 12% on AIME (GPT 4o) → IMO gold in ~ 15 months. We have come very far very quickly. I wouldn’t be surprised if by next year models will be deriving new theorems and contributing to original math research!

I was particularly motivated to work on this project because this win came from general research advancements. Beyond just math, we will improve on other capabilities and make ChatGPT more useful over the coming months.

Sebastien Bubeck: It’s hard to overstate the significance of this. It may end up looking like a “moon‑landing moment” for AI.

Just to spell it out as clearly as possible: a next-word prediction machine (because that’s really what it is here, no tools no nothing) just produced genuinely creative proofs for hard, novel math problems at a level reached only by an elite handful of pre‑college prodigies.

Nomore ID: Read Noam’s thread carefully.

Winning a gold medal at the 2025 IMO is an outstanding achievement, but in some ways, it might just be noise that grabbed the headlines.

They have recently developed new techniques that work much better on hard-to-verify problems, have extended TTC to several hours, and have improved thinking efficiency.

Jerry Tworek (OpenAI): Why am I excited about IMO results we just published:

– we did very little IMO-specific work, we just keep training general models

– all natural language proofs

– no evaluation harness

We needed a new research breakthrough and @alexwei_ and team delivered.

Diego Aud: Jerry, is this breakthrough included in GPT-5, or is it reserved for the next generation?

Jerry Tworek: It’s a later model probably end of year thing.

Guizin: Agent 1.

Jerry Tworek: I’m so limited by compute you wouldn’t believe it. Stargate can’t finish soon enough.

Going back to Tao’s objections, we know essentially nothing about this new model, or about what Google did to get their result. Given that P3 was unusually easy this year, these scores are perhaps not themselves that terribly impressive relative to expectations.

Can we trust this? It’s not like OpenAI has never misled us on such things in the past.

In terms of the result being worthy of a 35/42, I think we can mostly trust that. They shared the solution, in its garbled semi-English, and if there was something that would have lost them points I think someone would have spotted it by now.

In terms of OpenAI otherwise cheating, we don’t have any proof about this but I think the chances of this are quite low. There’s different kinds of deception or lies, different parts of OpenAI are differently trustworthy, and this kind of lie is not in their nature nor do they have much incentive to try it given the chance it gets exposed, and the fact that if it’s not real then they won’t be able to pay it off later.

The place where one might doubt the most is, can we trust that what OpenAI did this time is more general, in the ways they are claiming?

Gary Marcus: The paradox of the OpenAI IMO discussion is that the new model scored only slightly better than DeepMind’s system from last year (as @NeelNanda5 notes); but that we assume that the new model is far more general.

Yet we have not yet seen any direct evidence of that.

It can barely speak english.

The ‘barely speak English’ part makes the solution worse in some ways but actually makes me give their claims to be doing something different more credence rather than less. It also should worry anyone who wants to maintain monitorable chain of thought.

Then again, one could say that the version that does it better, and more naturally, is thus more important, for exactly the same reasons.

Vladimir Nesov: [GDM’s] is even more surprising than OpenAI’s entry (in its details). Since it can now write proofs well automatically (even if it costs a lot and takes a lot of time), in a few months regular reasoning models might get enough training data to reliably understand what proofs are directly, and that’s an important basic ingredient for STEM capabilities.

We only have OpenAI’s word on the details of how this went down. So what to think?

I am mostly inclined to believe them on the main thrust of what is going on. That doesn’t mean that this result will generalize. I do give them credit for having something that they believe came out of a general approach, and that they expect to generalize.

Still, it’s reasonable to ask what the catch might be, that there’s always going to be a catch. Certainly it is plausible that this was, as Miles suggested, RLed to within an inch of its life, and it starting to be unable to speak English is the opposite of what is claimed, that it is losing its generality, or things are otherwise going off the rails.

The thing is, to me this doesn’t feel like it is fake. It might not be a big deal, it might not transfer all that well to other contexts, but it doesn’t feel fake.

To wrap up, another reminder that no, you can’t pretend none of this matters, and both the Google and OpenAI results matter and should update you:

Cole Wyeth: The headline result was obviously going to happen, not an update for anyone paying attention.

Garrett Baker: “Obviously going to happen” is very different from ‘happens at this point in time rather than later or sooner and with this particular announcement by this particular company’. You should still update off this. Hell, I was pretty confident this would be first done by Google DeepMind, so its a large update for me (I don’t know what for yet though)!

Your claim “not an update for anyone paying attention” also seems false. I’m sure there are many who are updating off this who were paying attention, for whatever reason, as they likely should.

I generally dislike this turn of phrase as it serves literally no purpose but to denigrate people who are changing their mind in light of evidence, which is just a bad thing to do.

cdt: I think it was reasonable to expect GDM to achieve gold with an AlphaProof-like system. Achieving gold with a general LLM-reasoning system from GDM would be something else and it is important for discussion around this to not confuse one forecast for another.